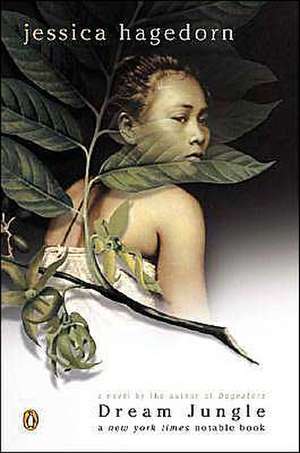

Dream Jungle

Autor Jessica Hagedornen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2004 – vârsta de la 18 ani

Jessica Hagedorn has received wide critical acclaim for her edgy, high-energy novels chronicling the clash and embrace of American and Filipino cultures. With Dream Jungle, she achieves a new level of narrative daring. Set in a Philippines of desperate beauty and rank corruption, Dream Jungle feverishly traces the consequences of two seemingly unrelated events: the discovery of an alleged ?lost tribe? and the arrival of a celebrity-studded American film crew filming an epic Vietnam War movie. Caught in the turmoil unleashed by these two incidents are four unforgettable characters?a wealthy, iconoclastic playboy, a woman ensnared in the sex industry, a Filipino-American writer, and a jaded actor?who find themselves drawn irrevocably together in this lavish, sensual portrait of a nation in crisis.

Preț: 123.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 186

Preț estimativ în valută:

23.67€ • 25.70$ • 19.88£

23.67€ • 25.70$ • 19.88£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780142001097

ISBN-10: 0142001090

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: b/w illustration on title page

Dimensiuni: 131 x 206 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

ISBN-10: 0142001090

Pagini: 336

Ilustrații: b/w illustration on title page

Dimensiuni: 131 x 206 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Recenzii

As beautiful as summer, as unforgettable as heartbreak . . . [A] luminous performance. (Junot Diaz, author of Drawn)

Notă biografică

Jessica Hagedorn is the author of the novels Dogeaters and The Gangster of Love, Dream Jungle, and a collection of poetry and short fiction, Danger and Beauty.

Extras

Zamora: 1971

How to explain that moment when Zamora López de Legazpi first laid eyes on them? Zamora’s gaze was steadfast and shameless. O they were beautiful, powerful, strange! Their fierce, wary eyes scrutinized him in return, taking in the brown, unruly curls on his head, the scraggly beard of his pale, unshaven face, the muscular arms and small, compact body that was, surprisingly, no taller than theirs. He had walked into a dream. Someone else’s dream—perhaps Duan’s—but now stolen and claimed by Zamora. The landscape of that dream—vast, ominous, shimmering blues and greens—was simply part of the loot.

The Himal people were not unfriendly; they could easily have killed him. One man demanded a cigarette, pointing to the Salems in Zamora’s jean jacket. Zamora gave him the entire pack. Another pointed to the ornate collar of brass, glass beads, and bone hanging from his wife’s neck, hoping Zamora would buy it. Zamora grinned and shook his head. Duan berated the man, who was crestfallen and backed away. The man’s wife fingered her precious necklace, relieved not to have to part with it. Others offered wads of flat green leaves to Zamora as a test, a gift. Zamora crammed the rolled-up leaves into his mouth, chewing and spitting as he saw the old women around him chewing and spitting. His tongue and lips became numb, but his other senses grew more acute. It was almost unbearable. Everything he saw and heard filled him with love. The tips of his fingers tingled. His eyes were wet with tears.

Children hid behind the long, dazzling skirts of their mothers, stealing glances at the hairy stranger. The old women of the tribe were the only ones who acted indifferent. Squatting comfortably on bony haunches, they turned their brown, haughty faces toward the heat of the sun, away from where Zamora stood with a goofy smile. The old women smelled trouble; they were disgusted with Duan for bringing the hairy Spaniard to them. The old women spit at the dirt and muttered curses under their breath, hoping to drive the stranger away. Tiny bells jangled on their brass anklets as the splayed toes of their cracked, bare feet burrowed into the hard, red earth.

Zamora López de Legazpi had been traveling for days to Lake Ramayyah. The lake, once filled with crocodiles and considered sacred by the Himal people, was located in Cotabato del Sur, the southernmost tip of the Philippine archipelago. It was Duan’s home, approximately 550 miles from Manila, as far from Zamora’s mansions, cars, polo horses, and beauty queens as anyone could imagine. Zamora had traveled first by helicopter, then by jeep, then on foot. He was led by Duan into the heart of a remote Himal village at the base of Mount Taobo, a grand, forbidding mountain. In the Himal language, Mount Taobo literally meant “mountain of the human being.” Zamora López de Legazpi stood in the shadow of the spectacular cordilleras surrounding Lake Ramayyah. Dense, rugged, green with trees, chains of dark mountains loomed in the clouds. That day he was a conquistador without an army, a rich man without his usual posse of bodyguards, photographers, doctors, PR flacks, cooks, and servants. That day his only friend was Duan, a man he did not trust. The thought was oddly liberating. Zamora kept chewing. The bitter, caustic juice of betel, tobacco, rock salt, and lime powder coated his tongue. Bliss.

Duan had repeatedly told him about the shy, mysterious people in the forest.

“Of course there are people in the forest! Why are you wasting my time with something I already know?” Zamora said, though he was intrigued. They were in a one- room shack made of cinder blocks and tin, what passed for a military outpost in the dusty, godforsaken town of Sultan Ramayyah. Zamora kicked the back of Duan’s leg. The older man grunted, taken by surprise. He was angry but did not dare show it. Duan was an elfin, toothless man of uncertain age who, while as poor as any Himal in this part of Mindanao, claimed to be a datu, a chieftain descended from a long, distinguished line of datus. Duan’s reputation as a skilled hunter and guide was legendary. He was fluent in several obscure tribal languages and dialects, and he knew enough rudimentary English and Tagalog to be useful to Zamora. Duan boasted of having three wives and seventeen children, yet he was a loner perfectly at ease roaming the Muslim settlements and isolated Jesuit missions nestled in the lush valleys below the mountains. Duan had known Zamora’s father, who once owned and controlled the profitable silver and copper mines in the region. But those days were long gone. Legazpi Mines now belonged to the government.

Duan rubbed the bruised calf of his leg where the Spaniard had kicked him. “These people are different,” Duan kept insisting, glad no one was in the room to witness his humiliation. The soldiers were outside, joking with Zamora’s bodyguard and pilot. “These people live in trees and caves. They are monkey people. Bat people.”

Zamora chuckled. “Are they poorer than poor? Do they have tails?”

“No,” Duan said. “They have no tails. But they climb and jump better than I can. I do not lie.” Duan’s voice grew whiny and higher as he became more agitated. “I am a datu,” he kept saying. “I do not lie.”

“Show me, prove it to me!” Zamora shouted. He lunged at Duan as if about to kick him again, then stopped himself. Both men stared at each other, breathing heavily. Zamora spoke after a long silence. “Lead me to them, Duan. Then you must promise to leave me alone with them. But if you are lying”—Zamora paused—“I will kill you.”

Duan’s people, the people in the village by the lake, watched in silence as Duan and Zamora made their way up the mountain. The old women shook their heads and covered their eyes, amazed at the two men’s foolishness. There were no trails, just clumps of thorny bush and vines, trickles of waterfall, walls of rocks and trees. The shrieking of birds and monkeys filled the air. The journey would take at least another four to six hours, Duan informed Zamora. Maybe ten. The thick mud made the going excruciatingly slow. It started to rain, gently at first. The steady patter of raindrops grew into a roar as the forest darkened. Zamora and Duan huddled together in the rotted-out cavity of a colossal tree trunk, forced to wait until the downpour ceased.

The rain stopped as abruptly as it had begun.

“We can go, boss,” Duan finally said.

Zamora and Duan crept out of the makeshift shelter, carefully wending their way through the dense, thorny bush until they reached a small clearing. “Wait here. I will tell them you have come,” Duan whispered before disappearing into the trees. Zamora collapsed on the muddy jungle floor and flung out his arms in joyful surrender. All that green. Humid, pulsating, unforgiving, alive with predators and scavengers. Zamora heard the triumphant screech of a monkey-eating eagle, imagined it pouncing on a startled tarsier. A yellow python uncoiled—swallowing an unsuspecting cloud rat, then a furious, screaming wild pig. Leeches dropped off jade vines in a sinister shower of welcome, slithering into Zamora’s ear canals and the corners of his eyes. He blinked in wonder as they fattened and gorged on his blood. Trees towered two hundred feet above him— Kekem, lunay, nabul, balete. God’s trees, so ancient and huge they obscured sky and sun. Such clichés he felt, such reverence and awe. A tingling in the loins, a fire in the belly you can only imagine. Ilang-ilang, waling-waling. Pungent perfume of wild, monstrous lilies and orchids in bloom. Pungent perfume of heaven, stink of fungus and mildew, bed of earth. Voracious green of dampness and rot. Green that lulled but also excited, green of exhaustion and thorns. Enchanted green of Lorca the poet. Ominous green of Mindanao rain forest.

Zamora would gladly die here, alone.

Just hours ago his knockout Teutonic goddess of a wife had sat up in bed and yelled out his name. ZAH-MO-RAH! She caught him just as he was about to sneak off in the gray light of dawn. “Why are you going to Mindanao? What is so important? Why? Why? Why?” The sounds of a car horn, honking once, twice. Sonny, his bodyguard, waited to drive him to the heliport. Sorry, baby. Gotta go. Ilse’s mouth turned down in a grimace. His name uttered again. This time softly. “Zamora.”

Come on, let’s hear it, darling.

“Today is Dulce’s birthday. Or have you forgotten? “

She turned away as he approached the bed. Zamora longed to reach out and kiss those parched lips, climb on top of that golden, clammy, perfect body and assure her that of course he had not forgotten his daughter’s birthday. But instead he left the room and fled down the stairs. Celia stood by the front door, ready with his bag and a thermos of black coffee. Good morning, sir. Her face betrayed nothing—though surely she had heard it all, heard Ilse railing at him just moments ago.

“Good morning,” Zamora said to Celia, who gazed at the floor. He raised his voice. “I said, ‘Good morning,’ Celia.”

Hers was barely audible. “Good morning, sir.”

“That’s better,” Zamora said.

Celia’s blush deepened. Zamora did not regret intimidating her. Her discomfort and unease excited him. He owed her a visit. He had not visited her in a long time, and he missed her. Celia was the yaya in charge of his infant son. She belonged to him. She was ordinary-looking but young, with lovely, burnished skin and a taut body. At first Celia used to run and hide from him. It became a game with them, even after the night Zamora took her to the poolhouse and deflowered her. Celia was seventeen then; she is nineteen now. She once made the mistake of daring to say she loved him. Minamahal kita . . . po, she had whispered in Tagalog. The “po” added as an afterthought, to signify respect.

Zamora’s response had been brusque and chilly. “But, dear girl, I love my wife.”

It amused Zamora to watch Celia, in her nervousness and haste, fumble with the lock on the front door. She finally got it open. The Mercedes idled in the driveway, Sonny at the wheel. Zamora stepped out into the rising heat. His arm brushed against Celia’s swollen breasts, making her jump.

Ilse! If only you were here. Fire ants swarm across my face, minuscule spiders bite through the cloth of my pants, I feel eyes. Not animal or insect eyes, but human eyes peering through the leaves at me. I open my mouth and begin to sing, imagining you, imagining my secret audience hunkered down in the bushes, their amazement and surprise at the sound of my sonorous voice. “What a diff’rence a day makes.”. . . A fluttering of wings. Your sigh. The rustling of leaves. The forest in an uproar as my voice booms and echoes. You run. I close my eyes and begin another random song, something I am sure my invisible audience would enjoy. “Cu cu rru cu cú, paloma . . . cu cu rru cu cú, no llores . . . las piedras jamás, Paloma, que van a saber de amores....” I open my eyes. A boy with hair down to his waist—thin, naked—creeps out of the bush and stands there, gawking at me.

The boy’s name, Zamora and the rest of the world would soon find out, was Bodabil. A born clown with a talent for mimicry, approximately ten years old. Maybe older, but none of the people in Bodabil’s tribe looked their age. The adults, by twenty-five, seemed as gnarled as the trees in their sacred forest.

Bodabil craned his neck to get a better view of Zamora. Duan had warned them all that the Spaniard was coming. A stranger so powerful that hair sprouted on his face; a stranger so powerful that he flew a whirling demon bird above the trees. Duan had spoken of the Spaniard with a certain proprietary air. “Be careful. The stranger carries anger inside him.”

Zamora kept singing, but softly now. Bodabil hooted and warbled in response, either in appreciation or in mockery of his singing. The boy’s reaction reassured Zamora. His singing faded down into quiet. Bodabil crept closer. Zamora lay still, did not dare move for fear the boy would bolt and run.

“Don’t be afraid,” Zamora whispered in English. He felt foolish—for why English? A twig snapped, but Zamora kept his eyes fixed on the canopy of dark trees above. “Don’t be afraid, mi hijito,” he continued in a low, gentle voice. Zamora added, in awkward Himal, “I am your Spirit Father, here to protect you.” There were eyes and ears everywhere, watching and listening. Bodabil froze in his tracks, surprised by the familiar words the stranger was uttering.

“My language,” Duan once said with pride to Zamora, “is understood by these cave people.”

“But how is that possible?” Zamora asked, immediately suspicious.

“Because I taught them,” Duan answered with a mischievous smile.

“How much time have you spent with them?”

Duan shrugged, feeling no need to offer the Spaniard any further explanation.

“All right,” Zamora said, “then teach me your language.”

Duan taught Zamora bino-bino, for “welcome”; maladong, for “companion”; lagtuk, which either meant “penis” or, with a slightly different intonation, “tree frog.” Over and over Duan repeated the crucial phrase for Zamora to say: Ago mong Amo Data, for “I am your Spirit Father.” Zamora had underestimated the wicked complexity of the Himal language. Nuance was everything. There were clicking words and gasping words, words that were quick intakes of breath, words that were harsh sighs of longing. One had to be careful about tone and inflection, to get it just right. Otherwise words could mean the exact opposite of what was intended. Just before he left Zamora alone in the clearing, Duan taught Zamora something else to say to the forest people, something important: Laan-lan, for “I mean you no harm.”

How to explain that moment when Zamora López de Legazpi first laid eyes on them? Zamora’s gaze was steadfast and shameless. O they were beautiful, powerful, strange! Their fierce, wary eyes scrutinized him in return, taking in the brown, unruly curls on his head, the scraggly beard of his pale, unshaven face, the muscular arms and small, compact body that was, surprisingly, no taller than theirs. He had walked into a dream. Someone else’s dream—perhaps Duan’s—but now stolen and claimed by Zamora. The landscape of that dream—vast, ominous, shimmering blues and greens—was simply part of the loot.

The Himal people were not unfriendly; they could easily have killed him. One man demanded a cigarette, pointing to the Salems in Zamora’s jean jacket. Zamora gave him the entire pack. Another pointed to the ornate collar of brass, glass beads, and bone hanging from his wife’s neck, hoping Zamora would buy it. Zamora grinned and shook his head. Duan berated the man, who was crestfallen and backed away. The man’s wife fingered her precious necklace, relieved not to have to part with it. Others offered wads of flat green leaves to Zamora as a test, a gift. Zamora crammed the rolled-up leaves into his mouth, chewing and spitting as he saw the old women around him chewing and spitting. His tongue and lips became numb, but his other senses grew more acute. It was almost unbearable. Everything he saw and heard filled him with love. The tips of his fingers tingled. His eyes were wet with tears.

Children hid behind the long, dazzling skirts of their mothers, stealing glances at the hairy stranger. The old women of the tribe were the only ones who acted indifferent. Squatting comfortably on bony haunches, they turned their brown, haughty faces toward the heat of the sun, away from where Zamora stood with a goofy smile. The old women smelled trouble; they were disgusted with Duan for bringing the hairy Spaniard to them. The old women spit at the dirt and muttered curses under their breath, hoping to drive the stranger away. Tiny bells jangled on their brass anklets as the splayed toes of their cracked, bare feet burrowed into the hard, red earth.

Zamora López de Legazpi had been traveling for days to Lake Ramayyah. The lake, once filled with crocodiles and considered sacred by the Himal people, was located in Cotabato del Sur, the southernmost tip of the Philippine archipelago. It was Duan’s home, approximately 550 miles from Manila, as far from Zamora’s mansions, cars, polo horses, and beauty queens as anyone could imagine. Zamora had traveled first by helicopter, then by jeep, then on foot. He was led by Duan into the heart of a remote Himal village at the base of Mount Taobo, a grand, forbidding mountain. In the Himal language, Mount Taobo literally meant “mountain of the human being.” Zamora López de Legazpi stood in the shadow of the spectacular cordilleras surrounding Lake Ramayyah. Dense, rugged, green with trees, chains of dark mountains loomed in the clouds. That day he was a conquistador without an army, a rich man without his usual posse of bodyguards, photographers, doctors, PR flacks, cooks, and servants. That day his only friend was Duan, a man he did not trust. The thought was oddly liberating. Zamora kept chewing. The bitter, caustic juice of betel, tobacco, rock salt, and lime powder coated his tongue. Bliss.

Duan had repeatedly told him about the shy, mysterious people in the forest.

“Of course there are people in the forest! Why are you wasting my time with something I already know?” Zamora said, though he was intrigued. They were in a one- room shack made of cinder blocks and tin, what passed for a military outpost in the dusty, godforsaken town of Sultan Ramayyah. Zamora kicked the back of Duan’s leg. The older man grunted, taken by surprise. He was angry but did not dare show it. Duan was an elfin, toothless man of uncertain age who, while as poor as any Himal in this part of Mindanao, claimed to be a datu, a chieftain descended from a long, distinguished line of datus. Duan’s reputation as a skilled hunter and guide was legendary. He was fluent in several obscure tribal languages and dialects, and he knew enough rudimentary English and Tagalog to be useful to Zamora. Duan boasted of having three wives and seventeen children, yet he was a loner perfectly at ease roaming the Muslim settlements and isolated Jesuit missions nestled in the lush valleys below the mountains. Duan had known Zamora’s father, who once owned and controlled the profitable silver and copper mines in the region. But those days were long gone. Legazpi Mines now belonged to the government.

Duan rubbed the bruised calf of his leg where the Spaniard had kicked him. “These people are different,” Duan kept insisting, glad no one was in the room to witness his humiliation. The soldiers were outside, joking with Zamora’s bodyguard and pilot. “These people live in trees and caves. They are monkey people. Bat people.”

Zamora chuckled. “Are they poorer than poor? Do they have tails?”

“No,” Duan said. “They have no tails. But they climb and jump better than I can. I do not lie.” Duan’s voice grew whiny and higher as he became more agitated. “I am a datu,” he kept saying. “I do not lie.”

“Show me, prove it to me!” Zamora shouted. He lunged at Duan as if about to kick him again, then stopped himself. Both men stared at each other, breathing heavily. Zamora spoke after a long silence. “Lead me to them, Duan. Then you must promise to leave me alone with them. But if you are lying”—Zamora paused—“I will kill you.”

Duan’s people, the people in the village by the lake, watched in silence as Duan and Zamora made their way up the mountain. The old women shook their heads and covered their eyes, amazed at the two men’s foolishness. There were no trails, just clumps of thorny bush and vines, trickles of waterfall, walls of rocks and trees. The shrieking of birds and monkeys filled the air. The journey would take at least another four to six hours, Duan informed Zamora. Maybe ten. The thick mud made the going excruciatingly slow. It started to rain, gently at first. The steady patter of raindrops grew into a roar as the forest darkened. Zamora and Duan huddled together in the rotted-out cavity of a colossal tree trunk, forced to wait until the downpour ceased.

The rain stopped as abruptly as it had begun.

“We can go, boss,” Duan finally said.

Zamora and Duan crept out of the makeshift shelter, carefully wending their way through the dense, thorny bush until they reached a small clearing. “Wait here. I will tell them you have come,” Duan whispered before disappearing into the trees. Zamora collapsed on the muddy jungle floor and flung out his arms in joyful surrender. All that green. Humid, pulsating, unforgiving, alive with predators and scavengers. Zamora heard the triumphant screech of a monkey-eating eagle, imagined it pouncing on a startled tarsier. A yellow python uncoiled—swallowing an unsuspecting cloud rat, then a furious, screaming wild pig. Leeches dropped off jade vines in a sinister shower of welcome, slithering into Zamora’s ear canals and the corners of his eyes. He blinked in wonder as they fattened and gorged on his blood. Trees towered two hundred feet above him— Kekem, lunay, nabul, balete. God’s trees, so ancient and huge they obscured sky and sun. Such clichés he felt, such reverence and awe. A tingling in the loins, a fire in the belly you can only imagine. Ilang-ilang, waling-waling. Pungent perfume of wild, monstrous lilies and orchids in bloom. Pungent perfume of heaven, stink of fungus and mildew, bed of earth. Voracious green of dampness and rot. Green that lulled but also excited, green of exhaustion and thorns. Enchanted green of Lorca the poet. Ominous green of Mindanao rain forest.

Zamora would gladly die here, alone.

Just hours ago his knockout Teutonic goddess of a wife had sat up in bed and yelled out his name. ZAH-MO-RAH! She caught him just as he was about to sneak off in the gray light of dawn. “Why are you going to Mindanao? What is so important? Why? Why? Why?” The sounds of a car horn, honking once, twice. Sonny, his bodyguard, waited to drive him to the heliport. Sorry, baby. Gotta go. Ilse’s mouth turned down in a grimace. His name uttered again. This time softly. “Zamora.”

Come on, let’s hear it, darling.

“Today is Dulce’s birthday. Or have you forgotten? “

She turned away as he approached the bed. Zamora longed to reach out and kiss those parched lips, climb on top of that golden, clammy, perfect body and assure her that of course he had not forgotten his daughter’s birthday. But instead he left the room and fled down the stairs. Celia stood by the front door, ready with his bag and a thermos of black coffee. Good morning, sir. Her face betrayed nothing—though surely she had heard it all, heard Ilse railing at him just moments ago.

“Good morning,” Zamora said to Celia, who gazed at the floor. He raised his voice. “I said, ‘Good morning,’ Celia.”

Hers was barely audible. “Good morning, sir.”

“That’s better,” Zamora said.

Celia’s blush deepened. Zamora did not regret intimidating her. Her discomfort and unease excited him. He owed her a visit. He had not visited her in a long time, and he missed her. Celia was the yaya in charge of his infant son. She belonged to him. She was ordinary-looking but young, with lovely, burnished skin and a taut body. At first Celia used to run and hide from him. It became a game with them, even after the night Zamora took her to the poolhouse and deflowered her. Celia was seventeen then; she is nineteen now. She once made the mistake of daring to say she loved him. Minamahal kita . . . po, she had whispered in Tagalog. The “po” added as an afterthought, to signify respect.

Zamora’s response had been brusque and chilly. “But, dear girl, I love my wife.”

It amused Zamora to watch Celia, in her nervousness and haste, fumble with the lock on the front door. She finally got it open. The Mercedes idled in the driveway, Sonny at the wheel. Zamora stepped out into the rising heat. His arm brushed against Celia’s swollen breasts, making her jump.

Ilse! If only you were here. Fire ants swarm across my face, minuscule spiders bite through the cloth of my pants, I feel eyes. Not animal or insect eyes, but human eyes peering through the leaves at me. I open my mouth and begin to sing, imagining you, imagining my secret audience hunkered down in the bushes, their amazement and surprise at the sound of my sonorous voice. “What a diff’rence a day makes.”. . . A fluttering of wings. Your sigh. The rustling of leaves. The forest in an uproar as my voice booms and echoes. You run. I close my eyes and begin another random song, something I am sure my invisible audience would enjoy. “Cu cu rru cu cú, paloma . . . cu cu rru cu cú, no llores . . . las piedras jamás, Paloma, que van a saber de amores....” I open my eyes. A boy with hair down to his waist—thin, naked—creeps out of the bush and stands there, gawking at me.

The boy’s name, Zamora and the rest of the world would soon find out, was Bodabil. A born clown with a talent for mimicry, approximately ten years old. Maybe older, but none of the people in Bodabil’s tribe looked their age. The adults, by twenty-five, seemed as gnarled as the trees in their sacred forest.

Bodabil craned his neck to get a better view of Zamora. Duan had warned them all that the Spaniard was coming. A stranger so powerful that hair sprouted on his face; a stranger so powerful that he flew a whirling demon bird above the trees. Duan had spoken of the Spaniard with a certain proprietary air. “Be careful. The stranger carries anger inside him.”

Zamora kept singing, but softly now. Bodabil hooted and warbled in response, either in appreciation or in mockery of his singing. The boy’s reaction reassured Zamora. His singing faded down into quiet. Bodabil crept closer. Zamora lay still, did not dare move for fear the boy would bolt and run.

“Don’t be afraid,” Zamora whispered in English. He felt foolish—for why English? A twig snapped, but Zamora kept his eyes fixed on the canopy of dark trees above. “Don’t be afraid, mi hijito,” he continued in a low, gentle voice. Zamora added, in awkward Himal, “I am your Spirit Father, here to protect you.” There were eyes and ears everywhere, watching and listening. Bodabil froze in his tracks, surprised by the familiar words the stranger was uttering.

“My language,” Duan once said with pride to Zamora, “is understood by these cave people.”

“But how is that possible?” Zamora asked, immediately suspicious.

“Because I taught them,” Duan answered with a mischievous smile.

“How much time have you spent with them?”

Duan shrugged, feeling no need to offer the Spaniard any further explanation.

“All right,” Zamora said, “then teach me your language.”

Duan taught Zamora bino-bino, for “welcome”; maladong, for “companion”; lagtuk, which either meant “penis” or, with a slightly different intonation, “tree frog.” Over and over Duan repeated the crucial phrase for Zamora to say: Ago mong Amo Data, for “I am your Spirit Father.” Zamora had underestimated the wicked complexity of the Himal language. Nuance was everything. There were clicking words and gasping words, words that were quick intakes of breath, words that were harsh sighs of longing. One had to be careful about tone and inflection, to get it just right. Otherwise words could mean the exact opposite of what was intended. Just before he left Zamora alone in the clearing, Duan taught Zamora something else to say to the forest people, something important: Laan-lan, for “I mean you no harm.”

Descriere

Hagedorn has received enormous critical acclaim for her edgy, high-energy novels chronicling the clash and embrace of American and Filipino cultures. With "Dream Jungle" she breaks through to a new level of narrative daring and has written her most complex and accomplished novel to date.