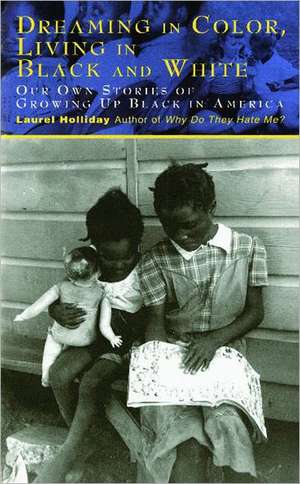

Dreaming In Color Living In Black And White: Our Own Stories of Growing Up Black in America

Autor Laurel Hollidayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 2 mai 2012 – vârsta de la 14 ani

“I constantly questioned myself as a child. All of the positive images of people I’d seen were white. To be beautiful, you not only had to be stick-skinny, with no behind, you had to have long silky blond hair and blue eyes, a thin nose, and thin lips. I just didn’t measure up.” —Charisse Nesbit, Maryland

These true stories from every part of America tell what it was like growing up in world where the color of people’s skin set them apart.

How do you feel when a teacher doesn’t believe that you wrote the story he thinks is great? How can you make friends and belong in a black school when your father is black and your mother is Puerto Rican? What do you do when you’re working in the kitchen of a summer camp in Vermont, but you’re not allowed to swim in the camp lake?

All the writers’ pain, confusion, humiliation, and rage are vividly expressed, but many of them went on to realize their dreams against overwhelming odds. Their voices offer hope, inspiration, and a challenge to us all.

Preț: 64.29 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 96

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.31€ • 13.37$ • 10.34£

12.31€ • 13.37$ • 10.34£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781442471771

ISBN-10: 1442471778

Pagini: 208

Ilustrații: f-c cvr

Dimensiuni: 127 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Simon Pulse

Colecția Simon Pulse

ISBN-10: 1442471778

Pagini: 208

Ilustrații: f-c cvr

Dimensiuni: 127 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Simon Pulse

Colecția Simon Pulse

Notă biografică

Laurel Holliday, formerly a college teacher, editor, and psychotherapist, now writes full time in Seattle. She is the award-winning author of the Children of Conflict series: Children in the Holocaust and World War II: Their Secret Diaries; Children of ?The Troubles?: Our Lives in the Crossfire of Northern Ireland; and Children of Israel, Children of Palestine: Our Own True Stories. Those three volumes were collected and abridged in the Archway Paperback edition titled Why Do They Hate Me?: Young Lives Caught in War and Conflict. Dreaming in Color, Living in Black and White is an abridged edition of Holliday?s fourth title in the Children of Conflict series, Children of the Dream: Our Own Stories of Growing Up Black in America. Laurel Holliday is also the author of Heartsongs, an international collection of young girls? diaries, which won a Best Book for Young Adults Award from the American Library Association.

Extras

CHAPTER 1 - Amitiyah Elayne Hyman

A minister in the Presbyterian church for eighteen years, Amitiyah Elayne Hyman began her own company called SpiritWorks in Washington, D.C., in 1998. Consulting with individuals and institutions, she designs prayers and rituals that assist people with self-acceptance, self-love, and the ability to be open and vulnerable to others. As a "mixed-blood woman," she brings African, Native American, and European traditions together in her rituals.

Amitiyah's writing also serves as a healing ritual. "Racism fed a cycle of abuse in which I was trapped as a child," she says, "and writing out this story helped me to heal from that abuse." In this true story she revisits the horror she felt in 1948, when she was first forced to defend herself against a racial epithet.

When I asked Amitiyah for her thoughts about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream, she said that it is no longer applicable. "The twenty-first century will be the time for people of color, the earth's majority, to come into their own. King's dream is too small for the future."

sticks and stones

and words and bones

We only met outside, in air that was cold and stung our faces, or in warm breezes that invited us to catch lightning bugs before bedtime. We cherished these sidewalk encounters, escapes from overheated kitchens and sun-starved hallways, an older sister's bossiness, and forced afternoon naps. They made us feel special, adventurous, beyond the limits imposed on kindergartners in a steel-workers' town on the Ohio River in 1948.

We would sit on the steps of the house between our two houses?a buffer zone that held our little end of the block, of blue collars and rednecks and black professionals, together. Swaddled in maroon corduroy leggings or knee-padded overalls, blue wool peacoats, rubber boots, and mismatched mittens that never wanted to stay on our hands, we enjoyed each other.

Passersby might have guessed that we were the best of friends, or cousins perhaps, from the way we whispered and laughed into each other's faces in the middle of winter. They would have missed that our faces were the colors of sweet vanilla and caramel cream, that my thick dark braids were rebelliously unraveling in the moist heat of my scalp, and that her short, straight blond hair was stringy and wet in the dampness. Our heads were hidden, sweating inside earmuffs and knitted caps, which taunting boys, from across the street, dusted white with well-aimed snowballs.

Our shovels, wooden sleds, and buckets lay nearby. Once we began to talk, they seemed to fall away, forgotten in the rush of intimacy. We discarded imaginary playmates, birthday gifts, and Christmas favorites as if they had been leaky boots or outgrown sweaters. Somehow we understood that as long as we stayed in the safe zone between our two houses and came when mothers clapped or called, we could continue the giggling and tickling and the whispering games we'd grown to love. We played patty-cake and hopscotch back and forth, first on one leg, then on the other, in foot-high mounds of snow.

Little Sally Walker, sitting in a saucer,

Wipe your weeping eyes.

Rise, Sally, rise.

At first we didn't notice that our mothers kept their distance. They never ventured out of shaded doorways or warm kitchens to chat or to see what was going on. They didn't join in our laughter and whispering. Instead, they vigilantly kept themselves apart, watching for us through screened doors and upstairs bedroom windows. We made an unspoken pact with them -- if they allowed us to cross yards and fences, then no one else need go beyond the boundaries or break invisible barriers set up by city sidewalks, conforming siblings, and disapproving fathers. Our little-girl forays compensated for grown-up dislikes and distances, for long held habits of fear.

She first said the words, after we marveled about the storm the night before and the way the moon said "hush" over the blanketed street. They fell out of her lips like jacks from her hand, plopping haphazardly onto the brick-and-concrete steps that had been shoveled earlier in the day. The sting of them sent tremors through my body that found a resting place in the soft tissues of my heart. They froze the spot and sent chills down my arms. They numbed my fingers.

"NIGGER. My daddy says that you're a NIGGER."

"Never let anyone call you NIGGER," was the mantra my father had drilled into my head.

Hot tears swirled up from somewhere deep, spilled out onto flushed cheeks, dripped into my lap. They warmed my hands and released my stiff fingers. I began to shake uncontrollably as I reached for a piece of brick, lying near the stoop, to steady myself. I snatched off my mittens. My fingers tore at the stone. Curling themselves around it, they locked onto its sharp, frozen hardness.

Sticks and stones can break my bones

but words can never harm me...

Sticks and stones can break bones and words...

Break bones and words can...

Harm me...

She saw the impact her words had upon my body as they flew from her thin lips, forming tiny darts of puffy gray-white air. They seemed to hang suspended in the stinging cold for an instant before they pierced my flesh. Then they disappeared into the frost. As if to prolong their power, she fired them rapidly, over and over again:

NIGGER, NIGGER, NIGGER, NIGGER,

Nigger,niggerniggerniggerniggernigger

niggerniggerniggernigger...

It was the way we played; we repeated grown-up words, trying them on for size the same way we donned dress-up clothes and pretended we were adults. If one word was sufficient, then we'd say ten for rhythm's sake. They tickled our mouths. It was fun, we thought, repeating grown-up words.

But I couldn't laugh with her. This word had hit its mark. I was impaled on it. In the background, I heard the drone of numerous warnings, the veiled threat of my gruff-voiced father. From that moment on, I believed that something terrible was going to happen to me. I knew I had set an unalterable chain of events into motion. I feared that they would avalanche, burying me in shame. I was cursed, doomed. I had let somebody call me "NIGGER." It wasn't just any old body, either; it was my friend. That really hurt.

Before I could stop myself, I wrenched out the loosened brick, heavy in my little girl's unmittened hand, and lifted it to her head, smashing it into her face. I heard the crack as it connected with her forehead in a well-positioned strike. The boys across the street howled and hooted their approval. She screamed in pain. Blood began to spread over her eyebrows, dripping into her eyes, rolling off her nose, down her snotty lips, and over her trembling chin. It pooled, making large polka dots on her play clothes.

For a moment we were freeze-framed by the clash of energies. Her words and my well-aimed brick had done what wary mothers could not do. The safe zone between our houses melted like snow, evaporating in the scorch of this ancient battle, begun by great-grandparents centuries ago. Now we played out the script. We ran to our mothers, scrambling in terror, falling in and out of snowdrifts. Skidding over the porch, I leapt into the vestibule, scattering icy wetness everywhere. I hurled myself through the doorway into the outstretched arms of my mother. She'd heard the wailing and had seen me coming from the lace-curtained living room window.

My father, who had been working in his second-floor study, raced downstairs to us. I was sobbing, and I didn't want to tell him what had happened. I was fearful of his wrath; after all, hadn't I let someone call me "NIGGER"? I had survived her teasing, but could I stand up to his hot anger? Too many tongue-lashings and belt strappings told me that was impossible.

My heart was hammering. I could have exploded. My chest wall, brains, and clenched teeth wanted to shatter like icicles into sharp pointy pieces. My father tried to wrench me loose from my mother. I tried to avoid his grip. Gasping for air, I twisted toward my mother and buried my face in her aproned belly.

The glass door of the house began to shake. My father whirled around in response to the pounding and the pacing on our porch. I saw her father's red menacing face. His shirttails flew from unbuttoned pants that he hadn't bothered to cover with a jacket. The two men glared at one another, straining shoulders, flexing arms, rocking back and forth on their heels. My father wore his slippers; her father had on metal-clipped boots. My mother peeled me loose from around her waist and took up a position at my father's side. Together they formed a phalanx, an impenetrable wall against him. Her father yelled and paced, threatening me and my parents.

Standing tall with stone-still faces, they held their ground. They refused him access to me. My father snarled as he spit words out: "I've told Elayne never to let anyone call her NIGGER. She was obeying my instructions."

What he didn't say in that moment was that he himself had called me "little nigger" more times than I care to remember. It was a mean "pet" phrase, handed down from one generation of colored to another. It migrated, in their mouths, from the deep south of Edisto Island, South Carolina, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It took up residence in his mouth. He used the phrase like a stick, stalking me and my older sister. Whenever we displeased him, he struck us with it. I felt helpless in those moments, unable to defend myself, knowing that I could not go up against this big man's insults with my little girl's body, my little girl's hate, my little girl's hurt.

All of those "little niggers" coalesced around the big one I'd heard just moments before. Together they formed a tight fist, knotting beneath the surface of my skin. The knot remains. That brick-bearing little girl stays with me. She is vigilant and available, should the need arise, to explode against taunts and bullies. Now she has a well-stocked arsenal and seldom wears mittens.

Our friendship ended on a day when brooding clouds swirled past steel mills, sullied snow drifted into puddles and onto porches. Our intimacy terminated with her father's insolent retreat from our porch. She traveled through icy streets, past snowbound buildings, to the hospital where doctors stitched her face. I cried, watching the empty street from my bedroom window. Cold wind stirred cruel words and frigid rage into a witches' brew of sticks and stones. Together they erased the spot where we had laughed and whispered, before the blood ran down.

Copyright © 2000 by Laurel Holliday

A minister in the Presbyterian church for eighteen years, Amitiyah Elayne Hyman began her own company called SpiritWorks in Washington, D.C., in 1998. Consulting with individuals and institutions, she designs prayers and rituals that assist people with self-acceptance, self-love, and the ability to be open and vulnerable to others. As a "mixed-blood woman," she brings African, Native American, and European traditions together in her rituals.

Amitiyah's writing also serves as a healing ritual. "Racism fed a cycle of abuse in which I was trapped as a child," she says, "and writing out this story helped me to heal from that abuse." In this true story she revisits the horror she felt in 1948, when she was first forced to defend herself against a racial epithet.

When I asked Amitiyah for her thoughts about Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream, she said that it is no longer applicable. "The twenty-first century will be the time for people of color, the earth's majority, to come into their own. King's dream is too small for the future."

sticks and stones

and words and bones

We only met outside, in air that was cold and stung our faces, or in warm breezes that invited us to catch lightning bugs before bedtime. We cherished these sidewalk encounters, escapes from overheated kitchens and sun-starved hallways, an older sister's bossiness, and forced afternoon naps. They made us feel special, adventurous, beyond the limits imposed on kindergartners in a steel-workers' town on the Ohio River in 1948.

We would sit on the steps of the house between our two houses?a buffer zone that held our little end of the block, of blue collars and rednecks and black professionals, together. Swaddled in maroon corduroy leggings or knee-padded overalls, blue wool peacoats, rubber boots, and mismatched mittens that never wanted to stay on our hands, we enjoyed each other.

Passersby might have guessed that we were the best of friends, or cousins perhaps, from the way we whispered and laughed into each other's faces in the middle of winter. They would have missed that our faces were the colors of sweet vanilla and caramel cream, that my thick dark braids were rebelliously unraveling in the moist heat of my scalp, and that her short, straight blond hair was stringy and wet in the dampness. Our heads were hidden, sweating inside earmuffs and knitted caps, which taunting boys, from across the street, dusted white with well-aimed snowballs.

Our shovels, wooden sleds, and buckets lay nearby. Once we began to talk, they seemed to fall away, forgotten in the rush of intimacy. We discarded imaginary playmates, birthday gifts, and Christmas favorites as if they had been leaky boots or outgrown sweaters. Somehow we understood that as long as we stayed in the safe zone between our two houses and came when mothers clapped or called, we could continue the giggling and tickling and the whispering games we'd grown to love. We played patty-cake and hopscotch back and forth, first on one leg, then on the other, in foot-high mounds of snow.

Little Sally Walker, sitting in a saucer,

Wipe your weeping eyes.

Rise, Sally, rise.

At first we didn't notice that our mothers kept their distance. They never ventured out of shaded doorways or warm kitchens to chat or to see what was going on. They didn't join in our laughter and whispering. Instead, they vigilantly kept themselves apart, watching for us through screened doors and upstairs bedroom windows. We made an unspoken pact with them -- if they allowed us to cross yards and fences, then no one else need go beyond the boundaries or break invisible barriers set up by city sidewalks, conforming siblings, and disapproving fathers. Our little-girl forays compensated for grown-up dislikes and distances, for long held habits of fear.

She first said the words, after we marveled about the storm the night before and the way the moon said "hush" over the blanketed street. They fell out of her lips like jacks from her hand, plopping haphazardly onto the brick-and-concrete steps that had been shoveled earlier in the day. The sting of them sent tremors through my body that found a resting place in the soft tissues of my heart. They froze the spot and sent chills down my arms. They numbed my fingers.

"NIGGER. My daddy says that you're a NIGGER."

"Never let anyone call you NIGGER," was the mantra my father had drilled into my head.

Hot tears swirled up from somewhere deep, spilled out onto flushed cheeks, dripped into my lap. They warmed my hands and released my stiff fingers. I began to shake uncontrollably as I reached for a piece of brick, lying near the stoop, to steady myself. I snatched off my mittens. My fingers tore at the stone. Curling themselves around it, they locked onto its sharp, frozen hardness.

Sticks and stones can break my bones

but words can never harm me...

Sticks and stones can break bones and words...

Break bones and words can...

Harm me...

She saw the impact her words had upon my body as they flew from her thin lips, forming tiny darts of puffy gray-white air. They seemed to hang suspended in the stinging cold for an instant before they pierced my flesh. Then they disappeared into the frost. As if to prolong their power, she fired them rapidly, over and over again:

NIGGER, NIGGER, NIGGER, NIGGER,

Nigger,niggerniggerniggerniggernigger

niggerniggerniggernigger...

It was the way we played; we repeated grown-up words, trying them on for size the same way we donned dress-up clothes and pretended we were adults. If one word was sufficient, then we'd say ten for rhythm's sake. They tickled our mouths. It was fun, we thought, repeating grown-up words.

But I couldn't laugh with her. This word had hit its mark. I was impaled on it. In the background, I heard the drone of numerous warnings, the veiled threat of my gruff-voiced father. From that moment on, I believed that something terrible was going to happen to me. I knew I had set an unalterable chain of events into motion. I feared that they would avalanche, burying me in shame. I was cursed, doomed. I had let somebody call me "NIGGER." It wasn't just any old body, either; it was my friend. That really hurt.

Before I could stop myself, I wrenched out the loosened brick, heavy in my little girl's unmittened hand, and lifted it to her head, smashing it into her face. I heard the crack as it connected with her forehead in a well-positioned strike. The boys across the street howled and hooted their approval. She screamed in pain. Blood began to spread over her eyebrows, dripping into her eyes, rolling off her nose, down her snotty lips, and over her trembling chin. It pooled, making large polka dots on her play clothes.

For a moment we were freeze-framed by the clash of energies. Her words and my well-aimed brick had done what wary mothers could not do. The safe zone between our houses melted like snow, evaporating in the scorch of this ancient battle, begun by great-grandparents centuries ago. Now we played out the script. We ran to our mothers, scrambling in terror, falling in and out of snowdrifts. Skidding over the porch, I leapt into the vestibule, scattering icy wetness everywhere. I hurled myself through the doorway into the outstretched arms of my mother. She'd heard the wailing and had seen me coming from the lace-curtained living room window.

My father, who had been working in his second-floor study, raced downstairs to us. I was sobbing, and I didn't want to tell him what had happened. I was fearful of his wrath; after all, hadn't I let someone call me "NIGGER"? I had survived her teasing, but could I stand up to his hot anger? Too many tongue-lashings and belt strappings told me that was impossible.

My heart was hammering. I could have exploded. My chest wall, brains, and clenched teeth wanted to shatter like icicles into sharp pointy pieces. My father tried to wrench me loose from my mother. I tried to avoid his grip. Gasping for air, I twisted toward my mother and buried my face in her aproned belly.

The glass door of the house began to shake. My father whirled around in response to the pounding and the pacing on our porch. I saw her father's red menacing face. His shirttails flew from unbuttoned pants that he hadn't bothered to cover with a jacket. The two men glared at one another, straining shoulders, flexing arms, rocking back and forth on their heels. My father wore his slippers; her father had on metal-clipped boots. My mother peeled me loose from around her waist and took up a position at my father's side. Together they formed a phalanx, an impenetrable wall against him. Her father yelled and paced, threatening me and my parents.

Standing tall with stone-still faces, they held their ground. They refused him access to me. My father snarled as he spit words out: "I've told Elayne never to let anyone call her NIGGER. She was obeying my instructions."

What he didn't say in that moment was that he himself had called me "little nigger" more times than I care to remember. It was a mean "pet" phrase, handed down from one generation of colored to another. It migrated, in their mouths, from the deep south of Edisto Island, South Carolina, to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It took up residence in his mouth. He used the phrase like a stick, stalking me and my older sister. Whenever we displeased him, he struck us with it. I felt helpless in those moments, unable to defend myself, knowing that I could not go up against this big man's insults with my little girl's body, my little girl's hate, my little girl's hurt.

All of those "little niggers" coalesced around the big one I'd heard just moments before. Together they formed a tight fist, knotting beneath the surface of my skin. The knot remains. That brick-bearing little girl stays with me. She is vigilant and available, should the need arise, to explode against taunts and bullies. Now she has a well-stocked arsenal and seldom wears mittens.

Our friendship ended on a day when brooding clouds swirled past steel mills, sullied snow drifted into puddles and onto porches. Our intimacy terminated with her father's insolent retreat from our porch. She traveled through icy streets, past snowbound buildings, to the hospital where doctors stitched her face. I cried, watching the empty street from my bedroom window. Cold wind stirred cruel words and frigid rage into a witches' brew of sticks and stones. Together they erased the spot where we had laughed and whispered, before the blood ran down.

Copyright © 2000 by Laurel Holliday

Cuprins

Introduction

Sticks and Stones and Words and Bones

Amitiyah Elayne Hyman

My First Friend (My Blond-Haired, Blue-Eyed Linda)

Marion Coleman Brown

Silver Stars

J. K. Dennis

Warmin? da Feet o? da Massa

Toni Pierce Webb

Freedom Summer

Sarah Bracey White

The Lesson

Dianne E. Dixon

Little Tigers Don?t Roar

Anthony Ross

Hitting Dante

Aya de Leon

All the Black Children

Antoine P. Reddick

Boomerism, or Doing Time in the Ivy League

Ben Bates

Fred

LeVan D. Hawkins

In the Belly of a Clothes Rack

Crystal Ann Williams

Child of the Dream

Charisse Nesbit

A True Friend?

Mia Threlkeld

A Waste of Yellow: Growing Up Black in America

Linnea Colette Ashley

Black Codes: Behavior in the Post-Civil Rights Era

Caille Millner

Selected Chronology

Credits

About the Author