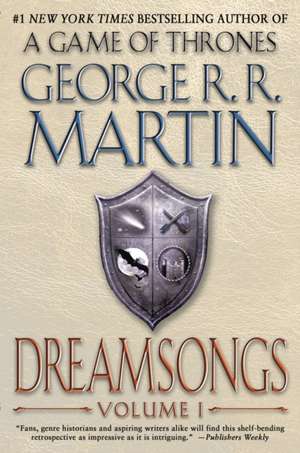

Dreamsongs, Volume I: Plato Versus Aristotle, and the Struggle for the Soul of Western Civilization

Autor George R. R. Martinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2012

Gathered here in Dreamsongs: Volume I are the very best of George R. R. Martin’s early works, including his Hugo, Nebula, and Bram Stoker awardߝwinning stories, cool fan pieces, and the original novella The Ice Dragon, from which Martin’s New York Times bestselling children’s book of the same title originated. A dazzling array of subjects and styles that features extensive author commentary, Dreamsongs, Volume I is the perfect collection for both Martin devotees and a new generation of fans.

“Fans, genre historians and aspiring writers alike will find this shelf-bending retrospective as impressive as it is intriguing.”—Publishers Weekly

“Dreamsongs is the ideal way to discover . . . a master of science fiction, fantasy and horror. . . . Martin is a writer like no other.”—The Guardian (U.K.)

PRAISE FOR GEORGE R. R. MARTIN

“Of those who work in the grand epic-fantasy tradition, Martin is by far the best. In fact . . . this is as good a time as any to proclaim him the American Tolkien.”—Time

“Long live George Martin . . . a literary dervish, enthralled by complicated characters and vivid language, and bursting with the wild vision of the very best tale tellers.”—The New York Times

“I always expect the best from George R. R. Martin, and he always delivers.”—Robert Jordan

Preț: 136.31 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 204

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.08€ • 27.33$ • 21.56£

26.08€ • 27.33$ • 21.56£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 21 martie-04 aprilie

Livrare express 07-13 martie pentru 54.50 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553385687

ISBN-10: 0553385682

Pagini: 683

Dimensiuni: 162 x 235 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Editura: Bantam

Colecția Bantam Books

ISBN-10: 0553385682

Pagini: 683

Dimensiuni: 162 x 235 x 38 mm

Greutate: 0.7 kg

Editura: Bantam

Colecția Bantam Books

Notă biografică

George R.R. Martin sold his first story in 1971 and has been writing professionally since then. He spent ten years in Hollywood as a writer-producer, working on The Twilight Zone, Beauty and the Beast, and various feature films and television pilots that were never made. In the mid ‘90s he returned to prose, his first love, and began work on his epic fantasy series, A Song of Ice and Fire. He has been in the Seven Kingdoms ever since. Whenever he’s allowed to leave, he returns to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he lives with the lovely Parris, and two cats named Augustus and Caligula, who think they run the place.

Extras

Chapter One

A Four-Color Fanboy

In the beginning, I told my tales to no one but myself.

Most of them existed only in my head, but once I learned to read and write I would sometimes put down bits on paper. The oldest surviving example of my writing, which looks like something I might have done in kindergarten or first grade, is an encyclopedia of outer space, block-printed in one of those school tablets with the marbled black and white covers. Each page has a drawing of a planet or a moon, and a few lines about its climate and its people. Real planets like Mars and Venus co-exist happily with ones I'd swiped from Flash Gordon and Rocky Jones, and others that I made up myself.

It's pretty cool, my encyclopedia, but it isn't finished. I was a lot better at starting stories than I was at finishing them. They were only things I made up to amuse myself.

Amusing myself was something I'd learned to do at a very early age. I was born on September 20, 1948, in Bayonne, New Jersey, the firstborn child of Raymond Collins Martin and Margaret Brady Martin. I don't recall having any playmates my own age until we moved into the projects when I was four. Before that, my parents lived in my great grandmother's house with my great grandmother, her sister, my grandmother, her brother, my parents, and me. Until my sister Darleen was born two years later, I was the only child. We had no kids next door either. Grandma Jones was a stubborn woman who refused to sell her house even after the rest of Broadway had gone commercial, so ours was the only residence for twenty blocks.

When I was four and Darleen was two and Janet was three years shy of being born, my parents finally moved into an apartment of their own in the new federal housing projects down on First Street. The word "projects" conjures up images of decaying high-rises set amongst grim concrete wastelands, but the LaTourette Gardens were not Cabrini-Green. The buildings stood three stories high, with six apartments on each floor. We had playgrounds and basketball courts, and across the street a park ran beside the oily waters of the Kill van Kull. It wasn't a bad place to grow up . . . and unlike Grandma Jones' house, there were other children around.

We swung on swings and slid down slides, went wading in the summer and had snowball fights in the winter, climbed trees and roller-skated, played stickball in the streets. When the other kids weren't around, I had comic books and television and toys to pass the time. Green plastic army men, cowboys with hats and vests and guns that you could swap around, knights and dinosaurs and spacemen. Like every red-blooded American kid, I knew the proper names of all the different dinosaurs (Brontosaurus, damn it, don't tell me any different). I made up the names for the knights and the spacemen.

At Mary Jane Donohoe School on Fifth Street, I learned to read with Dick and Jane and Sally and their dog, Spot. Run, Spot, run. See Spot run. Did you ever wonder why Spot runs so much? He's running away from Dick and Jane and Sally, the dullest family in the world. I wanted to run away from them as well, right back to my comic books . . . or "funny books," as we called them. My first exposure to the seminal works of western literature came through Classics Illustrated comics. I read Archie too, and Uncle Scrooge, and Cosmo the Merry Martian. But the Superman and Batman titles were my favorites . . . especially World's Finest Comics, where the two of them teamed up every month.

The first stories I can remember finishing were written on pages torn from my school tablets. They were scary stories about a monster hunter, and I sold them to the other kids in my building for a penny a page. The first story was a page long, and I got a penny. The next was two pages long, and went for two cents. A free dramatic reading was part of the deal; I was the best reader in the projects, renowned for my werewolf howls. The last story in my monster hunter series was five pages long and sold for a nickel, the price of a Milky Way, my favorite candy bar. I remember thinking I had it made. Write a story, buy a Milky Way. Life was sweet . . .

. . . until my best customer started having bad dreams, and told his mother about my monster stories. She came to my mother, who talked to my father, and that was that. I switched from monsters to spacemen (Jarn of Mars and his gang, I'll talk about them later), and stopped showing my stories to anyone.

But I kept reading comics. I saved them in a bookcase made from an orange crate, and over time my collection grew big enough to fill both shelves. When I was ten years old I read my first science fiction novel, and began buying paperbacks too. That stretched my budget thin. Caught in a financial crunch, at eleven I reached the momentous decision that I had grown "too old" for comics. They were fine for little kids, but I was almost a teenager. So I cleared out my orange crate, and my mother donated all my comics to Bayonne Hospital, for the kids in the sick ward to read.

(Dirty rotten sick kids. I want my comics back!)

My too-old-for-comics phase lasted perhaps a year. Every time I went into the candy store on Kelly Parkway to buy an Ace Double, the new comics were right there. I couldn't help but see the covers, and some of them looked so interesting . . . there were new stories, new heroes, whole new companies . . .

It was the first issue of Justice League of America that destroyed my year-old maturity. I had always loved World's Finest Comics, where Superman and Batman teamed up, but JLA brought together all the major DC heroes. The cover of that first issue showed the Flash playing chess against a three-eyed alien. The pieces were shaped like the members of the JLA, and whenever one was captured, the real hero disappeared. I had to have it.

Next thing I knew, the orange crate was filling up once more. And a good thing, too. Otherwise I might not have been at the comics rack in 1962, to stumble on the fourth issue of some weird-looking funny book that had the temerity to call itself "the World's Greatest Comic Magazine." It wasn't a DC. It was from an obscure, third-rate company best known for their not-very-scary monster comics . . . but it did seem to be a superhero team, which was my favorite thing. I bought it, even though it cost twelve cents (comics were meant to be a dime!), and thereby changed my life.

It was the World's Greatest Comic Magazine, actually. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were about to remake the world of funny books. The Fantastic Four broke all the rules. Their identities were not secret. One of them was a monster (the Thing, who at once became my favorite), at a time when all heroes were required to be handsome. They were a family, rather than a league or a society or a team. And like real families, they squabbled endlessly with one another. The DC heroes in the Justice League could only be told apart by their costumes and their hair colors (okay, the Atom was short, the Martian Manhunter was green, and Wonder Woman had breasts, but aside from that they were the same), but the Fantastic Four had personalities. Characterization had come to comics, and in 1961 that was a revelation and a revolution.

The first words of mine ever to appear in print were "Dear Stan and Jack."

They appeared in Fantastic Four #20, dated August 1963, in the letter column. My letter of comment was insightful, intelligent, analytical—the main thrust of it was that Shakespeare had better move on over now that Stan Lee had arrived. At the end of my words of approbation, Stan and Jack printed my name and address.

Soon after, a chain letter turned up in my mailbox.

Mail for me? That was astonishing. It was the summer between my freshman and sophomore years at Marist High School, and everyone I knew lived in either Bayonne or Jersey City. Nobody wrote me letters. But here was this list of names, and it said that if I sent a quarter to the name at the top of the list, removed the top name and added mine at the bottom, then sent out four copies, in a few weeks I'd get $64 in quarters. That was enough to keep me in funny books and Milky Ways for years to come. So I scotch-taped a quarter to an index card, put it in an envelope, mailed it off to the name at the top of the list, and sat back to await my riches.

I never got a single quarter, damn it.

Instead I got something much more interesting. It so happened that the guy at the top of the list published a comic fanzine, priced at twenty-five cents. No doubt he mistook my quarter for an order. The 'zine he sent me was printed in faded purple (that was "ditto," I would learn later), badly written and crudely drawn, but I didn't care. It had articles and editorials and letters and pinups and even amateur comic strips, starring heroes I had never heard of. And there were reviews of other fanzines too, some of which sounded even cooler. I mailed off more sticky quarters, and before long I was up to my neck in the infant comics fandom of the '60s.

Today, comics are big business. The San Diego Comicon has grown into a mammoth trade show that draws crowds ten times the size of science fiction's annual WorldCon. Some small independent comics are still coming out, and comicdom has its trade journals and adzines as well, but no true fanzines as they were in days of yore. The moneychangers long ago took over the temple. In the ultimate act of obscenity, Golden Age comics are bought and sold inside slabs of mylar to insure that their owners can never actually read them, and risk decreasing their value as collectibles (whoever thought of that should be sealed inside a slab of mylar himself, if you ask me). No one calls them "funny books" anymore.

Forty years ago it was very different. Comics fandom was in its infancy. Comicons were just starting up (I was at the first one in 1964, held in one room in Manhattan, and organized by a fan named Len Wein, who went on to run both DC and Marvel and create Wolverine), but there were hundreds of fanzines. A few, like Alter Ego, were published by actual adults with jobs and lives and wives, but most were written, drawn, and edited by kids no older than myself. The best were professionally printed by photo-offset or letterpress, but those were few. The second tier were done on mimeograph machines, like most of the science fiction fanzines of the day. The majority relied on spirit duplicators, hektographs, or xerox. (The Rocket's Blast, which went on to become one of comicdom's largest fanzines, was reproduced by carbon paper when it began, which gives you some idea of how large a circulation it had).

Almost all the fanzines included a page or two of ads, where the readers could offer back issues for sale and list the comics they wanted to buy. In one such ad, I saw that some guy from Arlington, Texas, was selling The Brave and the Bold #28, the issue that introduced the JLA. I mailed off a sticky quarter, and the guy in Texas sent the funny book with a cardboard stiffener on which he'd drawn a rather good barbarian warrior. That was how my lifelong friendship with Howard Waldrop began. How long ago? Well, John F. Kennedy flew down to Dallas not long after.

My involvement in this strange and wondrous world did not end with reading fanzines. Having been published in the Fantastic Four, it was no challenge to get my letters printed by fanzines. Before long I was seeing my name in print all over the place. Stan and Jack published more of my LOCs as well. Down the slippery slope I went, from letters to short articles, and then a regular column in a fanzine called The Comic World News, where I offered suggestions on how comics I did not like could be "saved." I did some art for TCWN as well, despite the handicap of not being able to draw. I even had one cover published: a picture of the Human Torch spelling out the fanzine's name in fiery letters. Since the Torch was a vague human outline surrounded by flames, he was easier to draw than characters who had noses and mouths and fingers and muscles and stuff.

When I was a freshman at Marist, my dream was still to be an astronaut . . . and not just your regular old astronaut, but the first man on the moon. I still recall the day one of the brothers asked each of us what we wanted to be, and the entire class burst into raucous laughter at my answer. By junior year, a different brother assigned us to research our chosen careers, and I researched fiction writing (and learned that the average fiction writer made $1200 a year from his stories, a discovery almost as appalling as that laughter two years earlier). Something profound had happened to me in between, to change my dreams for good and all. That something was comics fandom. It was during my sophomore and junior years at Marist that I first began to write actual stories for the fanzines.

I had an ancient manual typewriter that I'd found in Aunt Gladys' attic, and had fooled around on it enough to become a real one-finger wonder. The black half of the black-and-red ribbon was so worn you could hardly read the type, but I made up for that by pounding the keys so hard they incised the letters into the paper. The inner parts of the "e" and "o" often fell right out, leaving holes. The red half of the ribbon was comparatively fresh; I used red for emphasis, since I didn't know anything about italics. I didn't know about margins, doublespacing, or carbon paper either.

My first stories starred a superhero come to Earth from outer space, like Superman. Unlike Superman, however, my guy did not have a super physique. In fact, he had no physique at all, since he lacked a body. He was a brain in a goldfish bowl. Not the most original of notions; brains in jars were a staple of both print SF and comics, although usually they were the villains. Making my brain-in-a-jar the good guy seemed a terrific twist to me.

From the Hardcover edition.

A Four-Color Fanboy

In the beginning, I told my tales to no one but myself.

Most of them existed only in my head, but once I learned to read and write I would sometimes put down bits on paper. The oldest surviving example of my writing, which looks like something I might have done in kindergarten or first grade, is an encyclopedia of outer space, block-printed in one of those school tablets with the marbled black and white covers. Each page has a drawing of a planet or a moon, and a few lines about its climate and its people. Real planets like Mars and Venus co-exist happily with ones I'd swiped from Flash Gordon and Rocky Jones, and others that I made up myself.

It's pretty cool, my encyclopedia, but it isn't finished. I was a lot better at starting stories than I was at finishing them. They were only things I made up to amuse myself.

Amusing myself was something I'd learned to do at a very early age. I was born on September 20, 1948, in Bayonne, New Jersey, the firstborn child of Raymond Collins Martin and Margaret Brady Martin. I don't recall having any playmates my own age until we moved into the projects when I was four. Before that, my parents lived in my great grandmother's house with my great grandmother, her sister, my grandmother, her brother, my parents, and me. Until my sister Darleen was born two years later, I was the only child. We had no kids next door either. Grandma Jones was a stubborn woman who refused to sell her house even after the rest of Broadway had gone commercial, so ours was the only residence for twenty blocks.

When I was four and Darleen was two and Janet was three years shy of being born, my parents finally moved into an apartment of their own in the new federal housing projects down on First Street. The word "projects" conjures up images of decaying high-rises set amongst grim concrete wastelands, but the LaTourette Gardens were not Cabrini-Green. The buildings stood three stories high, with six apartments on each floor. We had playgrounds and basketball courts, and across the street a park ran beside the oily waters of the Kill van Kull. It wasn't a bad place to grow up . . . and unlike Grandma Jones' house, there were other children around.

We swung on swings and slid down slides, went wading in the summer and had snowball fights in the winter, climbed trees and roller-skated, played stickball in the streets. When the other kids weren't around, I had comic books and television and toys to pass the time. Green plastic army men, cowboys with hats and vests and guns that you could swap around, knights and dinosaurs and spacemen. Like every red-blooded American kid, I knew the proper names of all the different dinosaurs (Brontosaurus, damn it, don't tell me any different). I made up the names for the knights and the spacemen.

At Mary Jane Donohoe School on Fifth Street, I learned to read with Dick and Jane and Sally and their dog, Spot. Run, Spot, run. See Spot run. Did you ever wonder why Spot runs so much? He's running away from Dick and Jane and Sally, the dullest family in the world. I wanted to run away from them as well, right back to my comic books . . . or "funny books," as we called them. My first exposure to the seminal works of western literature came through Classics Illustrated comics. I read Archie too, and Uncle Scrooge, and Cosmo the Merry Martian. But the Superman and Batman titles were my favorites . . . especially World's Finest Comics, where the two of them teamed up every month.

The first stories I can remember finishing were written on pages torn from my school tablets. They were scary stories about a monster hunter, and I sold them to the other kids in my building for a penny a page. The first story was a page long, and I got a penny. The next was two pages long, and went for two cents. A free dramatic reading was part of the deal; I was the best reader in the projects, renowned for my werewolf howls. The last story in my monster hunter series was five pages long and sold for a nickel, the price of a Milky Way, my favorite candy bar. I remember thinking I had it made. Write a story, buy a Milky Way. Life was sweet . . .

. . . until my best customer started having bad dreams, and told his mother about my monster stories. She came to my mother, who talked to my father, and that was that. I switched from monsters to spacemen (Jarn of Mars and his gang, I'll talk about them later), and stopped showing my stories to anyone.

But I kept reading comics. I saved them in a bookcase made from an orange crate, and over time my collection grew big enough to fill both shelves. When I was ten years old I read my first science fiction novel, and began buying paperbacks too. That stretched my budget thin. Caught in a financial crunch, at eleven I reached the momentous decision that I had grown "too old" for comics. They were fine for little kids, but I was almost a teenager. So I cleared out my orange crate, and my mother donated all my comics to Bayonne Hospital, for the kids in the sick ward to read.

(Dirty rotten sick kids. I want my comics back!)

My too-old-for-comics phase lasted perhaps a year. Every time I went into the candy store on Kelly Parkway to buy an Ace Double, the new comics were right there. I couldn't help but see the covers, and some of them looked so interesting . . . there were new stories, new heroes, whole new companies . . .

It was the first issue of Justice League of America that destroyed my year-old maturity. I had always loved World's Finest Comics, where Superman and Batman teamed up, but JLA brought together all the major DC heroes. The cover of that first issue showed the Flash playing chess against a three-eyed alien. The pieces were shaped like the members of the JLA, and whenever one was captured, the real hero disappeared. I had to have it.

Next thing I knew, the orange crate was filling up once more. And a good thing, too. Otherwise I might not have been at the comics rack in 1962, to stumble on the fourth issue of some weird-looking funny book that had the temerity to call itself "the World's Greatest Comic Magazine." It wasn't a DC. It was from an obscure, third-rate company best known for their not-very-scary monster comics . . . but it did seem to be a superhero team, which was my favorite thing. I bought it, even though it cost twelve cents (comics were meant to be a dime!), and thereby changed my life.

It was the World's Greatest Comic Magazine, actually. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby were about to remake the world of funny books. The Fantastic Four broke all the rules. Their identities were not secret. One of them was a monster (the Thing, who at once became my favorite), at a time when all heroes were required to be handsome. They were a family, rather than a league or a society or a team. And like real families, they squabbled endlessly with one another. The DC heroes in the Justice League could only be told apart by their costumes and their hair colors (okay, the Atom was short, the Martian Manhunter was green, and Wonder Woman had breasts, but aside from that they were the same), but the Fantastic Four had personalities. Characterization had come to comics, and in 1961 that was a revelation and a revolution.

The first words of mine ever to appear in print were "Dear Stan and Jack."

They appeared in Fantastic Four #20, dated August 1963, in the letter column. My letter of comment was insightful, intelligent, analytical—the main thrust of it was that Shakespeare had better move on over now that Stan Lee had arrived. At the end of my words of approbation, Stan and Jack printed my name and address.

Soon after, a chain letter turned up in my mailbox.

Mail for me? That was astonishing. It was the summer between my freshman and sophomore years at Marist High School, and everyone I knew lived in either Bayonne or Jersey City. Nobody wrote me letters. But here was this list of names, and it said that if I sent a quarter to the name at the top of the list, removed the top name and added mine at the bottom, then sent out four copies, in a few weeks I'd get $64 in quarters. That was enough to keep me in funny books and Milky Ways for years to come. So I scotch-taped a quarter to an index card, put it in an envelope, mailed it off to the name at the top of the list, and sat back to await my riches.

I never got a single quarter, damn it.

Instead I got something much more interesting. It so happened that the guy at the top of the list published a comic fanzine, priced at twenty-five cents. No doubt he mistook my quarter for an order. The 'zine he sent me was printed in faded purple (that was "ditto," I would learn later), badly written and crudely drawn, but I didn't care. It had articles and editorials and letters and pinups and even amateur comic strips, starring heroes I had never heard of. And there were reviews of other fanzines too, some of which sounded even cooler. I mailed off more sticky quarters, and before long I was up to my neck in the infant comics fandom of the '60s.

Today, comics are big business. The San Diego Comicon has grown into a mammoth trade show that draws crowds ten times the size of science fiction's annual WorldCon. Some small independent comics are still coming out, and comicdom has its trade journals and adzines as well, but no true fanzines as they were in days of yore. The moneychangers long ago took over the temple. In the ultimate act of obscenity, Golden Age comics are bought and sold inside slabs of mylar to insure that their owners can never actually read them, and risk decreasing their value as collectibles (whoever thought of that should be sealed inside a slab of mylar himself, if you ask me). No one calls them "funny books" anymore.

Forty years ago it was very different. Comics fandom was in its infancy. Comicons were just starting up (I was at the first one in 1964, held in one room in Manhattan, and organized by a fan named Len Wein, who went on to run both DC and Marvel and create Wolverine), but there were hundreds of fanzines. A few, like Alter Ego, were published by actual adults with jobs and lives and wives, but most were written, drawn, and edited by kids no older than myself. The best were professionally printed by photo-offset or letterpress, but those were few. The second tier were done on mimeograph machines, like most of the science fiction fanzines of the day. The majority relied on spirit duplicators, hektographs, or xerox. (The Rocket's Blast, which went on to become one of comicdom's largest fanzines, was reproduced by carbon paper when it began, which gives you some idea of how large a circulation it had).

Almost all the fanzines included a page or two of ads, where the readers could offer back issues for sale and list the comics they wanted to buy. In one such ad, I saw that some guy from Arlington, Texas, was selling The Brave and the Bold #28, the issue that introduced the JLA. I mailed off a sticky quarter, and the guy in Texas sent the funny book with a cardboard stiffener on which he'd drawn a rather good barbarian warrior. That was how my lifelong friendship with Howard Waldrop began. How long ago? Well, John F. Kennedy flew down to Dallas not long after.

My involvement in this strange and wondrous world did not end with reading fanzines. Having been published in the Fantastic Four, it was no challenge to get my letters printed by fanzines. Before long I was seeing my name in print all over the place. Stan and Jack published more of my LOCs as well. Down the slippery slope I went, from letters to short articles, and then a regular column in a fanzine called The Comic World News, where I offered suggestions on how comics I did not like could be "saved." I did some art for TCWN as well, despite the handicap of not being able to draw. I even had one cover published: a picture of the Human Torch spelling out the fanzine's name in fiery letters. Since the Torch was a vague human outline surrounded by flames, he was easier to draw than characters who had noses and mouths and fingers and muscles and stuff.

When I was a freshman at Marist, my dream was still to be an astronaut . . . and not just your regular old astronaut, but the first man on the moon. I still recall the day one of the brothers asked each of us what we wanted to be, and the entire class burst into raucous laughter at my answer. By junior year, a different brother assigned us to research our chosen careers, and I researched fiction writing (and learned that the average fiction writer made $1200 a year from his stories, a discovery almost as appalling as that laughter two years earlier). Something profound had happened to me in between, to change my dreams for good and all. That something was comics fandom. It was during my sophomore and junior years at Marist that I first began to write actual stories for the fanzines.

I had an ancient manual typewriter that I'd found in Aunt Gladys' attic, and had fooled around on it enough to become a real one-finger wonder. The black half of the black-and-red ribbon was so worn you could hardly read the type, but I made up for that by pounding the keys so hard they incised the letters into the paper. The inner parts of the "e" and "o" often fell right out, leaving holes. The red half of the ribbon was comparatively fresh; I used red for emphasis, since I didn't know anything about italics. I didn't know about margins, doublespacing, or carbon paper either.

My first stories starred a superhero come to Earth from outer space, like Superman. Unlike Superman, however, my guy did not have a super physique. In fact, he had no physique at all, since he lacked a body. He was a brain in a goldfish bowl. Not the most original of notions; brains in jars were a staple of both print SF and comics, although usually they were the villains. Making my brain-in-a-jar the good guy seemed a terrific twist to me.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Even before "A Game of Thrones," Martin had already established himself as a giant in the field of fantasy literature. The first of two stunning collections, this volume is a rare treat for readers, offering fascinating insight into his journey from young writer to award-winning master.