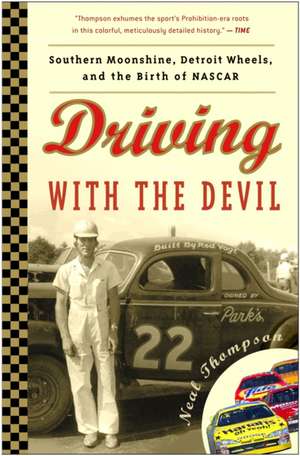

Driving with the Devil: Southern Moonshine, Detroit Wheels, and the Birth of NASCAR

Autor Neal Thompsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2007

Today’s NASCAR is a family sport with 75 million loyal fans, which is growing bigger and more mainstream by the day. Part Disney, part Vegas, part Barnum & Bailey, NASCAR is also a multibillion-dollar business and a cultural phenomenon that transcends geography, class, and gender. But dark secrets lurk in NASCAR’s past.

Driving with the Devil uncovers for the first time the true story behind NASCAR’s distant, moonshine-fueled origins and paints a rich portrait of the colorful men who created it. Long before the sport of stock-car racing even existed, young men in the rural, Depression-wracked South had figured out that cars and speed were tickets to a better life. With few options beyond the farm or factory, the best chance of escape was running moonshine. Bootlegging offered speed, adventure, and wads of cash—if the drivers survived. Driving with the Devil is the story of bootleggers whose empires grew during Prohibition and continued to thrive well after Repeal, and of drivers who thundered down dusty back roads with moonshine deliveries, deftly outrunning federal agents. The car of choice was the Ford V-8, the hottest car of the 1930s, and ace mechanics tinkered with them until they could fly across mountain roads at 100 miles an hour.

After fighting in World War II, moonshiners transferred their skills to the rough, red-dirt racetracks of Dixie, and a national sport was born. In this dynamic era (1930s and ’40s), three men with a passion for Ford V-8s—convicted criminal Ray Parks, foul-mouthed mechanic Red Vogt, and crippled war veteran Red Byron, NASCAR’s first champion—emerged as the first stock car “team.” Theirs is the violent, poignant story of how moonshine and fast cars merged to create a new sport for the South to call its own.

Driving with the Devil is a fascinating look at the well-hidden historical connection between whiskey running and stock-car racing. NASCAR histories will tell you who led every lap of every race since the first official race in 1948. Driving with the Devil goes deeper to bring you the excitement, passion, crime, and death-defying feats of the wild, early days that NASCAR has carefully hidden from public view. In the tradition of Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit, this tale not only reveals a bygone era of a beloved sport, but also the character of the country at a moment in time.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 100.65 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 151

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.26€ • 19.96$ • 16.08£

19.26€ • 19.96$ • 16.08£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400082261

ISBN-10: 1400082269

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: 16-PAGE B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1400082269

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: 16-PAGE B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Neal Thompson is a veteran journalist who has worked for the Baltimore Sun, Philadelphia Inquirer, and St. Petersburg Times, and whose magazine stories have appeared in Outside, Esquire, Backpacker, and Men’s Health. He teaches at the University of North Carolina-Asheville’s Great Smokies Writing Program and is author of Light This Candle: The Life & Times of Alan Shepard, America’s First Spaceman. Thompson, his wife, and their two sons live in the mountains outside Asheville, North Carolina.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Tell about the South. What’s it like there?

Why do they live there? Why do they live at all?

—William Faulkner

1

“NASCAR is no longer a southern sport”

The old man has seen a lot. Sometimes too much. Police in his rearview mirror. The inside of jail cells. Friends and family lowered into the ground. Race cars carving deadly paths into crowds. He’s seen stacks of money, too—some coming, some going.

Those visions, those memories, all link into a story. The real story.

The old man sits behind his orderly desk sipping a Coke, almost as if he’s waiting for someone to come through the door and ask, “Tell me what it was like.” It is the start of the twenty-first century, but he is dressed in the style of an earlier era: white shirt and narrow black tie, a gray jacket and felt fedora on a nearby hook—the same uniform he’s worn since FDR’s first term, except for summers, when the fedora is swapped for a straw boater. Raymond Parks is a creature of habit. He doesn’t need to be here each day. With moonshining profits earned as a teen, he bought liquor stores, then vending machines, which funded real estate deals and other sources of income (some legal, some not quite). Far from his squalid youth, Parks is worth plenty, more than he could have imagined. He’s sold off most of his empire—the houses, the land, the nightclubs, the vending machines, and all of his liquor stores except one. Still, he arrives each morning to putter around the office, make phone calls, check his accounts.

Next door, customers trickle into the one package store Parks has kept, the one he’s owned for two-thirds of a century. They buy flasks of Jack Daniels and fifths of Wild Turkey from a brother-in-law who has worked for Parks since World War II. Even now, it’s an ironic business for a teetotaler who—as a so-called moonshine “baron” and “kingpin”—used to make, deliver, and profit nicely from illegal corn whiskey. Outside, crews of Georgia road workers jackhammer into his parking lot, part of a road-widening project that brings Atlanta’s Northside Avenue closer to the bespectacled old man’s front door each day.

Parks is ninety-one, though he looks two decades younger. In his twilight years, this office has become a sanctuary and the place he goes to rummage through the past. The room contains the secrets of NASCAR’s origins. On cluttered walls and shelves are the dinged-up and tarnished trophies and loving cups, the yellowed newspaper articles, the vivid black-and-white photographs of men and machines, of crowds and crack-ups, which tell part of the story of how NASCAR came to be.

Take a look: one of Parks’s drivers is balanced impossibly on two right wheels in the north turn of the old Beach-and-Road course at Daytona; the wizard mechanic who honed his skills juicing up whiskey cars poses on the fender of a 1939 Ford V-8 coupe outside his “24-Hour” garage, wearing his trademark white T-shirt, white pants, and white socks; a driver stands next to his race car in front of Parks’s office / liquor store in 1948, a dozen trophies lined up before him and Miss Atlanta smiling at his side.

Parks is proud of the recent photos, too. It took many years for him to return to the sport he abandoned in 1952. When he did, NASCAR stars such as Dale Earnhardt—his arm affectionately around Parks’s shoulder—embraced him as their sport’s unsung pioneer.

There were good reasons he’d left the sport a half century earlier. That world contained dark secrets like prison and murder, greed and betrayal, the frequent maiming of friends and colleagues, their innocent fans, and the violent death of a young child. Parks keeps a few mementos from that chapter of the NASCAR story tucked neatly inside thick black photo albums, home also to faded pictures of whiskey stills, war-ravaged German cities, and a sheet-draped corpse being loaded into a hearse.

The corpse had been Parks’s cousin and stock car racing’s first true star. He had been like a son to Parks. The day after his greatest racing victory, just as his sport was about to take off, he died. As usual, moonshine was to blame.

*

Except for Violet—the most beautiful of his five wives, whom he married a decade ago at the age of eighty—Parks is often alone now. He survived his previous wives and his lone son. He outlived all the racers whose careers he launched, including his friend and fellow war veteran Red Byron, who, despite a leg full of Japanese shrapnel, became NASCAR’s first champion. He outlived Bill France, too, his wily friend who presided dictator-like over NASCAR’s first quarter century. A handful of racers from the 1940s and ’50s are still kicking around, but none of the major players from those seminal, post-Depression days before there was a NASCAR. Even Dale Earnhardt, the man who brought NASCAR to the masses, is gone, killed at Daytona in 2001.

After abruptly leaving the sport in 1952, Parks watched in awe as NASCAR evolved into something that was unthinkable back in those uneasy years before and after World War II. In the late 1930s, at dusty red-dirt tracks, a victor would be lucky to take home $300 for a win—if the promoter didn’t run off with the purse. Now, a single NASCAR racing tire costs more than $300, and a win on any given Sunday is worth half a million.

Over the years, a few hard-core fans, amateur historians, or magazine writers have tracked Parks down. They stop by to scan his photographs, to tap into his memories of the rowdy races on red-clay tracks, the guns and women and fistfights and white liquor, the days before NASCAR existed. Most days, he works in his office alone, or with Violet by his side. He is the sole living keeper of NASCAR’s true history, but his memory is fading, and Violet frets about that. In his tenth decade, Parks—the ex-felon, the war veteran, the self- made millionaire and philanthropist—has finally begun to slow down.

The “sport” that Parks helped create became a multibillion-dollar industry. It evolved from rural, workingman’s domain into an attraction—often an obsession—for eighty million loyal fans. Today’s NASCAR, still owned by a single family, is a phenomenon, a churning moneymaker—equal parts Disney, Vegas, and Ringling Brothers—and the second most popular sport in America, with races that regularly attract two hundred thousand spectators. No longer a second-tier event on ESPN2, races are now televised nationally on NBC, TNT, and FOX and in 2007 will begin airing on ABC, ESPN, and other networks, part of a TV contract worth nearly $5 billion.

With the help of sophisticated merchandising, marketing, and soaring corporate sponsorship, NASCAR continues growing beyond the South, faster than ever, becoming more mainstream by the day. NASCAR’s red- white-and-blue logo is splashed on cereal boxes in supermarket aisles, on magazine covers, beer cans, clothing, even leather recliners. Try driving any major highway, even in the Northeast, without seeing NASCAR devotions glued to bumpers. Recent additions to the list of $20-million-a-year race car sponsors include Viagra and, reflective of NASCAR’s growing female fan base, Brawny paper towels, Tide, and Betty Crocker. In a sign of NASCAR’s relentless hunger for profit, it even rescinded a long-standing ban against liquor sponsors to allow Jack Daniels and Jim Beam to endorse cars in 2005.

In 2004, NASCAR’s longtime top sponsor—cigarette maker R. J. Reynolds, which had been introduced to NASCAR in 1972 by a convicted moonshiner—was replaced by communications giant Nextel. That $750- million deal symbolized not only the sport’s modern era but the continued decline of the South’s ideological dominance of the sport. As Richard Petty has said, “NASCAR is no longer a southern sport.”

Today, NASCAR’s fan base has found a happy home in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Dallas, Kansas City, and Chicago. Plans are even afoot for a racetrack near New York City. Most fans are college-educated, middle- aged, middle-class homeowners; nearly half are women. At a time when some pro baseball teams play before paltry crowds of a few thousand, attendance at NASCAR events grows by 10 percent a year. Average attendance at a NASCAR Nextel Cup race is nearly 200,000, three times bigger than the average NFL football game. The sport’s stars are millionaire celebrities who appear in rock videos, date supermodels, and live in mansions. When Dale Earnhardt died, millions of Americans wept, as did Parks, who was there that day in 2001 when Earnhardt slammed into the wall at Daytona. The prolonged mourning for Earnhardt—the sport’s Elvis—opened the eyes of more than a few non–NASCAR fans.

As NASCAR’s popularity continues to spread, the sport is becoming a symbol of America itself. But how did NASCAR happen at all? And why? The answers lie in the complicated, whiskey-soaked history of the South.

*

It’s safe to say few of today’s NASCAR fans know the name Raymond Parks, nor the monkey named Jocko, the busty pit-road groupies and brash female racers, the moonshining drivers named Fonty, Soapy, Speedy, Smokey, Cannonball, Jap, Cotton, Gober, and Crash. Nor the two intense, freckled friends named Red, one of whom came up with the name NASCAR—the “National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing”—and the other of whom became the sport’s first champion. And its second.

Unlike baseball and football, which celebrate their pioneers and early heroes, most of the dirt-poor southerners who founded stock car racing have died or retired into obscurity. There is no Babe Ruth or Ty Cobb, not even an Abner Doubleday. A few NASCAR names from the 1950s and ’60s might still resonate among hard-cores: Junior Johnson, Curtis Turner, Fireball Roberts. It’s occasionally noted that Richard Petty’s father, Lee, and Dale Earnhardt’s pop, Ralph, were aggressive, dirt-smeared racing pioneers. But, despite the many books that have proliferated during NASCAR’s recent rise to nationwide popularity, the names of Raymond Parks, Red Byron, Red Vogt, Lloyd Seay, and Roy Hall rarely appear in print.

Maybe that’s because of NASCAR’s dirty little secret: moonshine.

The sport’s distant, whiskey-fueled origins are usually wrapped into a neat, vague little clause—“. . . whose early racers were bootleggers . . .”—about as noncommittal to the deeper truth as crediting pigs for their contribution to football. Today, if the fans know anything about NASCAR’s origins, they might know the name Bill France. The tall, megaphone-voiced racer/promoter from D.C. deftly managed to get himself named NASCAR’s first president in 1947, then eventually bought out the organization’s other top officers and stockholders to make himself sole proprietor of a sport that became his personal dynasty. France is often referred to as NASCAR’s “founder,” which is oversimplification bordering on fiction. Largely forgotten from the NASCAR story is this: Bill France used to race for, borrow money, and seek advice from a moonshine baron and convicted felon from Atlanta named Raymond Parks.

According to the minutes of the historic 1947 organizational meeting in Daytona Beach at which NASCAR was born, France envisioned an everyman’s sport with “distinct possibilities for Sunday shows. . . . We don’t know how big it can be if it’s handled properly.” Many people over the years—including, right from the start, Raymond Parks and the two Reds—have argued that France did not handle things properly. NASCAR certainly succeeded far beyond anyone’s wildest postwar expectations, thanks in large part to the moonshiners who were its first and best racers. But France held a deep disdain for the whiskey drivers who nurtured NASCAR’s gestation and its early years. He worked hard to distance his sport from those roots and was not above blackballing any dissenters, as Parks and both of the Reds discovered.

In striving to create squeaky-clean family entertainment, to the point of downplaying NASCAR’s crime-tainted origins, France buried the more dramatic parts of NASCAR’s story beneath the all-American mythology he preferred. Efforts to portray stock car racing as a family sport continue to this day. In 2004, Dale Earnhardt Jr. was fined $10,000 for saying “shit” on national television; he declined to apologize, saying that anyone tuned in to a stock car race shouldn’t be surprised by a four-letter word. And in 2006, just before the Daytona 500, NASCAR President Mike Helton told reporters in Washington (Bill France’s hometown) that “the old Southeastern redneck heritage that we had is no longer in existence.” After a backlash from fans, Helton backpedaled, saying NASCAR was “proud of where we came from.” Despite the lip service, in its reach to a wider audience, NASCAR seems to be losing its vernacular and, in the words of The Washington Post, “shedding its past as if it were an embarrassing family secret.”

Bill France, for better or worse, commandeered stock car racing, declared himself its king, appropriated its coffers and history, leaving the real but untidy story behind. He transformed an unruly hobby into a monopoly, then rewrote the past.

This book, therefore, is the previously untold story of how Raymond Parks, his moonshining cousins, and their four-letter-word-using friends from the red-dirt hills of North Georgia helped create the sport that Bill France ultimately made his own.

In the South, where the Great Depression infected deeper and festered longer than elsewhere, there were few escape routes. Folks couldn’t venture into the city for a baseball game or a movie because there weren’t enough cities, transportation was limited, and the smaller towns rarely had a theater. There were no big-time sports, either (the Braves wouldn’t settle in Atlanta until 1965, and the Falcons a year later). It was all cotton fields, unemployed farmers, and Depression-silenced mills, mines, and factories. But if you were lucky enough to have a nearby fairgrounds or an enterprising farmer who’d turned his barren field into a racetrack, maybe you’d have had a chance to stand beside a chicken-wire fence and watch Lloyd Seay in his jacked-up Ford V-8 tearing around the oval, a symbol of power for the powerless. But Seay’s racing career would get violently cut short by his moonshining career, and World War II would interrupt the entire sport’s progression for nearly five years. It wasn’t until after the war that southern racing, helped by an unlikely hero with a war-crippled leg, regained its footing and momentum. The rough, violent years of 1945 through 1950 would then unfold as the most outrageous years of NASCAR’s colorful history.

For those who were a part of it, who saw it and felt it, it was incredible.

*

This is not a book about NASCAR. It’s the story of what happened in Atlanta, in Daytona Beach, and a handful of smaller southern towns before and after World War II. It’s the story of what happened when moonshine and the automobile collided, and how puritanical Henry Ford and the forces of Prohibition and war all inadvertently helped the southern moonshiners and their gnarly sport. NASCAR historians can tell you who led every lap of every race since the organization’s first official contest was won in 1948 by a man named Red Byron. But they can’t—or won’t—say much about what happened in the decade before that. If Abner Doubleday allegedly invented baseball and James Naismith created basketball with peach baskets and soccer balls at a YMCA, then who created NASCAR?

The answer: a bunch of motherless, dirt-poor southern teens driving with the devil in jacked-up Fords full of corn whiskey. Because long before there were stock cars, there were Ford V-8 whiskey cars—the best means of escape a southern boy could wish for.

From the Hardcover edition.

Why do they live there? Why do they live at all?

—William Faulkner

1

“NASCAR is no longer a southern sport”

The old man has seen a lot. Sometimes too much. Police in his rearview mirror. The inside of jail cells. Friends and family lowered into the ground. Race cars carving deadly paths into crowds. He’s seen stacks of money, too—some coming, some going.

Those visions, those memories, all link into a story. The real story.

The old man sits behind his orderly desk sipping a Coke, almost as if he’s waiting for someone to come through the door and ask, “Tell me what it was like.” It is the start of the twenty-first century, but he is dressed in the style of an earlier era: white shirt and narrow black tie, a gray jacket and felt fedora on a nearby hook—the same uniform he’s worn since FDR’s first term, except for summers, when the fedora is swapped for a straw boater. Raymond Parks is a creature of habit. He doesn’t need to be here each day. With moonshining profits earned as a teen, he bought liquor stores, then vending machines, which funded real estate deals and other sources of income (some legal, some not quite). Far from his squalid youth, Parks is worth plenty, more than he could have imagined. He’s sold off most of his empire—the houses, the land, the nightclubs, the vending machines, and all of his liquor stores except one. Still, he arrives each morning to putter around the office, make phone calls, check his accounts.

Next door, customers trickle into the one package store Parks has kept, the one he’s owned for two-thirds of a century. They buy flasks of Jack Daniels and fifths of Wild Turkey from a brother-in-law who has worked for Parks since World War II. Even now, it’s an ironic business for a teetotaler who—as a so-called moonshine “baron” and “kingpin”—used to make, deliver, and profit nicely from illegal corn whiskey. Outside, crews of Georgia road workers jackhammer into his parking lot, part of a road-widening project that brings Atlanta’s Northside Avenue closer to the bespectacled old man’s front door each day.

Parks is ninety-one, though he looks two decades younger. In his twilight years, this office has become a sanctuary and the place he goes to rummage through the past. The room contains the secrets of NASCAR’s origins. On cluttered walls and shelves are the dinged-up and tarnished trophies and loving cups, the yellowed newspaper articles, the vivid black-and-white photographs of men and machines, of crowds and crack-ups, which tell part of the story of how NASCAR came to be.

Take a look: one of Parks’s drivers is balanced impossibly on two right wheels in the north turn of the old Beach-and-Road course at Daytona; the wizard mechanic who honed his skills juicing up whiskey cars poses on the fender of a 1939 Ford V-8 coupe outside his “24-Hour” garage, wearing his trademark white T-shirt, white pants, and white socks; a driver stands next to his race car in front of Parks’s office / liquor store in 1948, a dozen trophies lined up before him and Miss Atlanta smiling at his side.

Parks is proud of the recent photos, too. It took many years for him to return to the sport he abandoned in 1952. When he did, NASCAR stars such as Dale Earnhardt—his arm affectionately around Parks’s shoulder—embraced him as their sport’s unsung pioneer.

There were good reasons he’d left the sport a half century earlier. That world contained dark secrets like prison and murder, greed and betrayal, the frequent maiming of friends and colleagues, their innocent fans, and the violent death of a young child. Parks keeps a few mementos from that chapter of the NASCAR story tucked neatly inside thick black photo albums, home also to faded pictures of whiskey stills, war-ravaged German cities, and a sheet-draped corpse being loaded into a hearse.

The corpse had been Parks’s cousin and stock car racing’s first true star. He had been like a son to Parks. The day after his greatest racing victory, just as his sport was about to take off, he died. As usual, moonshine was to blame.

*

Except for Violet—the most beautiful of his five wives, whom he married a decade ago at the age of eighty—Parks is often alone now. He survived his previous wives and his lone son. He outlived all the racers whose careers he launched, including his friend and fellow war veteran Red Byron, who, despite a leg full of Japanese shrapnel, became NASCAR’s first champion. He outlived Bill France, too, his wily friend who presided dictator-like over NASCAR’s first quarter century. A handful of racers from the 1940s and ’50s are still kicking around, but none of the major players from those seminal, post-Depression days before there was a NASCAR. Even Dale Earnhardt, the man who brought NASCAR to the masses, is gone, killed at Daytona in 2001.

After abruptly leaving the sport in 1952, Parks watched in awe as NASCAR evolved into something that was unthinkable back in those uneasy years before and after World War II. In the late 1930s, at dusty red-dirt tracks, a victor would be lucky to take home $300 for a win—if the promoter didn’t run off with the purse. Now, a single NASCAR racing tire costs more than $300, and a win on any given Sunday is worth half a million.

Over the years, a few hard-core fans, amateur historians, or magazine writers have tracked Parks down. They stop by to scan his photographs, to tap into his memories of the rowdy races on red-clay tracks, the guns and women and fistfights and white liquor, the days before NASCAR existed. Most days, he works in his office alone, or with Violet by his side. He is the sole living keeper of NASCAR’s true history, but his memory is fading, and Violet frets about that. In his tenth decade, Parks—the ex-felon, the war veteran, the self- made millionaire and philanthropist—has finally begun to slow down.

The “sport” that Parks helped create became a multibillion-dollar industry. It evolved from rural, workingman’s domain into an attraction—often an obsession—for eighty million loyal fans. Today’s NASCAR, still owned by a single family, is a phenomenon, a churning moneymaker—equal parts Disney, Vegas, and Ringling Brothers—and the second most popular sport in America, with races that regularly attract two hundred thousand spectators. No longer a second-tier event on ESPN2, races are now televised nationally on NBC, TNT, and FOX and in 2007 will begin airing on ABC, ESPN, and other networks, part of a TV contract worth nearly $5 billion.

With the help of sophisticated merchandising, marketing, and soaring corporate sponsorship, NASCAR continues growing beyond the South, faster than ever, becoming more mainstream by the day. NASCAR’s red- white-and-blue logo is splashed on cereal boxes in supermarket aisles, on magazine covers, beer cans, clothing, even leather recliners. Try driving any major highway, even in the Northeast, without seeing NASCAR devotions glued to bumpers. Recent additions to the list of $20-million-a-year race car sponsors include Viagra and, reflective of NASCAR’s growing female fan base, Brawny paper towels, Tide, and Betty Crocker. In a sign of NASCAR’s relentless hunger for profit, it even rescinded a long-standing ban against liquor sponsors to allow Jack Daniels and Jim Beam to endorse cars in 2005.

In 2004, NASCAR’s longtime top sponsor—cigarette maker R. J. Reynolds, which had been introduced to NASCAR in 1972 by a convicted moonshiner—was replaced by communications giant Nextel. That $750- million deal symbolized not only the sport’s modern era but the continued decline of the South’s ideological dominance of the sport. As Richard Petty has said, “NASCAR is no longer a southern sport.”

Today, NASCAR’s fan base has found a happy home in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Dallas, Kansas City, and Chicago. Plans are even afoot for a racetrack near New York City. Most fans are college-educated, middle- aged, middle-class homeowners; nearly half are women. At a time when some pro baseball teams play before paltry crowds of a few thousand, attendance at NASCAR events grows by 10 percent a year. Average attendance at a NASCAR Nextel Cup race is nearly 200,000, three times bigger than the average NFL football game. The sport’s stars are millionaire celebrities who appear in rock videos, date supermodels, and live in mansions. When Dale Earnhardt died, millions of Americans wept, as did Parks, who was there that day in 2001 when Earnhardt slammed into the wall at Daytona. The prolonged mourning for Earnhardt—the sport’s Elvis—opened the eyes of more than a few non–NASCAR fans.

As NASCAR’s popularity continues to spread, the sport is becoming a symbol of America itself. But how did NASCAR happen at all? And why? The answers lie in the complicated, whiskey-soaked history of the South.

*

It’s safe to say few of today’s NASCAR fans know the name Raymond Parks, nor the monkey named Jocko, the busty pit-road groupies and brash female racers, the moonshining drivers named Fonty, Soapy, Speedy, Smokey, Cannonball, Jap, Cotton, Gober, and Crash. Nor the two intense, freckled friends named Red, one of whom came up with the name NASCAR—the “National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing”—and the other of whom became the sport’s first champion. And its second.

Unlike baseball and football, which celebrate their pioneers and early heroes, most of the dirt-poor southerners who founded stock car racing have died or retired into obscurity. There is no Babe Ruth or Ty Cobb, not even an Abner Doubleday. A few NASCAR names from the 1950s and ’60s might still resonate among hard-cores: Junior Johnson, Curtis Turner, Fireball Roberts. It’s occasionally noted that Richard Petty’s father, Lee, and Dale Earnhardt’s pop, Ralph, were aggressive, dirt-smeared racing pioneers. But, despite the many books that have proliferated during NASCAR’s recent rise to nationwide popularity, the names of Raymond Parks, Red Byron, Red Vogt, Lloyd Seay, and Roy Hall rarely appear in print.

Maybe that’s because of NASCAR’s dirty little secret: moonshine.

The sport’s distant, whiskey-fueled origins are usually wrapped into a neat, vague little clause—“. . . whose early racers were bootleggers . . .”—about as noncommittal to the deeper truth as crediting pigs for their contribution to football. Today, if the fans know anything about NASCAR’s origins, they might know the name Bill France. The tall, megaphone-voiced racer/promoter from D.C. deftly managed to get himself named NASCAR’s first president in 1947, then eventually bought out the organization’s other top officers and stockholders to make himself sole proprietor of a sport that became his personal dynasty. France is often referred to as NASCAR’s “founder,” which is oversimplification bordering on fiction. Largely forgotten from the NASCAR story is this: Bill France used to race for, borrow money, and seek advice from a moonshine baron and convicted felon from Atlanta named Raymond Parks.

According to the minutes of the historic 1947 organizational meeting in Daytona Beach at which NASCAR was born, France envisioned an everyman’s sport with “distinct possibilities for Sunday shows. . . . We don’t know how big it can be if it’s handled properly.” Many people over the years—including, right from the start, Raymond Parks and the two Reds—have argued that France did not handle things properly. NASCAR certainly succeeded far beyond anyone’s wildest postwar expectations, thanks in large part to the moonshiners who were its first and best racers. But France held a deep disdain for the whiskey drivers who nurtured NASCAR’s gestation and its early years. He worked hard to distance his sport from those roots and was not above blackballing any dissenters, as Parks and both of the Reds discovered.

In striving to create squeaky-clean family entertainment, to the point of downplaying NASCAR’s crime-tainted origins, France buried the more dramatic parts of NASCAR’s story beneath the all-American mythology he preferred. Efforts to portray stock car racing as a family sport continue to this day. In 2004, Dale Earnhardt Jr. was fined $10,000 for saying “shit” on national television; he declined to apologize, saying that anyone tuned in to a stock car race shouldn’t be surprised by a four-letter word. And in 2006, just before the Daytona 500, NASCAR President Mike Helton told reporters in Washington (Bill France’s hometown) that “the old Southeastern redneck heritage that we had is no longer in existence.” After a backlash from fans, Helton backpedaled, saying NASCAR was “proud of where we came from.” Despite the lip service, in its reach to a wider audience, NASCAR seems to be losing its vernacular and, in the words of The Washington Post, “shedding its past as if it were an embarrassing family secret.”

Bill France, for better or worse, commandeered stock car racing, declared himself its king, appropriated its coffers and history, leaving the real but untidy story behind. He transformed an unruly hobby into a monopoly, then rewrote the past.

This book, therefore, is the previously untold story of how Raymond Parks, his moonshining cousins, and their four-letter-word-using friends from the red-dirt hills of North Georgia helped create the sport that Bill France ultimately made his own.

In the South, where the Great Depression infected deeper and festered longer than elsewhere, there were few escape routes. Folks couldn’t venture into the city for a baseball game or a movie because there weren’t enough cities, transportation was limited, and the smaller towns rarely had a theater. There were no big-time sports, either (the Braves wouldn’t settle in Atlanta until 1965, and the Falcons a year later). It was all cotton fields, unemployed farmers, and Depression-silenced mills, mines, and factories. But if you were lucky enough to have a nearby fairgrounds or an enterprising farmer who’d turned his barren field into a racetrack, maybe you’d have had a chance to stand beside a chicken-wire fence and watch Lloyd Seay in his jacked-up Ford V-8 tearing around the oval, a symbol of power for the powerless. But Seay’s racing career would get violently cut short by his moonshining career, and World War II would interrupt the entire sport’s progression for nearly five years. It wasn’t until after the war that southern racing, helped by an unlikely hero with a war-crippled leg, regained its footing and momentum. The rough, violent years of 1945 through 1950 would then unfold as the most outrageous years of NASCAR’s colorful history.

For those who were a part of it, who saw it and felt it, it was incredible.

*

This is not a book about NASCAR. It’s the story of what happened in Atlanta, in Daytona Beach, and a handful of smaller southern towns before and after World War II. It’s the story of what happened when moonshine and the automobile collided, and how puritanical Henry Ford and the forces of Prohibition and war all inadvertently helped the southern moonshiners and their gnarly sport. NASCAR historians can tell you who led every lap of every race since the organization’s first official contest was won in 1948 by a man named Red Byron. But they can’t—or won’t—say much about what happened in the decade before that. If Abner Doubleday allegedly invented baseball and James Naismith created basketball with peach baskets and soccer balls at a YMCA, then who created NASCAR?

The answer: a bunch of motherless, dirt-poor southern teens driving with the devil in jacked-up Fords full of corn whiskey. Because long before there were stock cars, there were Ford V-8 whiskey cars—the best means of escape a southern boy could wish for.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Thompson exhumes the sport's Prohibition-era roots in this colorful, meticulously detailed history."

-Time Magazine

“Here’s the real story, not just of NASCAR, but of the new South that emerged from moonshine and speed.”

—Richard Ben Cramer, author of Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life and editor of The Best American Sports Writing 2004

“Neal Thompson has written NASCAR’s Glory of Their Times. He tells the true story of NASCAR’s beginnings, revealing the sport’s strong whiskey roots and letting us get to know its key movers and shakers, including the triumvirate of racer Red Byron, mechanic Red Vogt, and bootlegger car owner Raymond Parks. Like Seabiscuit, Thompson makes a sport and an era come wonderfully alive.”

—Peter Golenbock, author of Miracle: Bobby Allison and the Saga of the Alabama Gang and American Zoom: Stock Car Racing—From Dirt Tracks to Daytona

“Driving with the Devil is a full-tilt excursion through the back roads of NASCAR’s past, when moonshiners and scofflaws pioneered the sport. This is a tale that sanitized corporate NASCAR would rather forget about, but with Neal Thompson at the wheel, it makes for wonderful reading.”

—Sharyn McCrumb, author of St. Dale

“Driving with the Devil is a treasure trove of historically relevant information that tracks the history of the American automobile industry, the culture and morality of the broader society, and the motivations and personalities of early stock-car-racing operatives. All of which have inexorably contributed to the foundation and fabric of NASCAR’s brand of stock-car racing as it manifests itself today.”

—Jack Roush, chairman of Roush Racing

“Driving with the Devil is a most impressive piece of work. Most Americans have the vague notion that big-time stock-car racing sprang from moonshine-hauling in the southern Appalachians prior to the Second World War, but here is documented proof that it was that and much more. Neal Thompson’s Driving with the Devil nails it once and for all: a riveting report any student of Americana will cherish. It’s no more about racing than The Old Man and the Sea is about fishing.”

—Paul Hemphill, author of Lovesick Blues: The Life of Hank Williams and Wheels: A Season on NASCAR’s Winston Cup Circuit

"A fascinating and fast-moving account of NASCAR's fledgling days."

–Atlanta Journal Constitution

"There are more divorces, drunks and wrecks than you can shake a checkered flag at...A thoroughly researched account of a 'simpler time' in a sport that has since become a multi-billion dollar business."

–NBC News anchor Brian Williams, in the Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.

-Time Magazine

“Here’s the real story, not just of NASCAR, but of the new South that emerged from moonshine and speed.”

—Richard Ben Cramer, author of Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life and editor of The Best American Sports Writing 2004

“Neal Thompson has written NASCAR’s Glory of Their Times. He tells the true story of NASCAR’s beginnings, revealing the sport’s strong whiskey roots and letting us get to know its key movers and shakers, including the triumvirate of racer Red Byron, mechanic Red Vogt, and bootlegger car owner Raymond Parks. Like Seabiscuit, Thompson makes a sport and an era come wonderfully alive.”

—Peter Golenbock, author of Miracle: Bobby Allison and the Saga of the Alabama Gang and American Zoom: Stock Car Racing—From Dirt Tracks to Daytona

“Driving with the Devil is a full-tilt excursion through the back roads of NASCAR’s past, when moonshiners and scofflaws pioneered the sport. This is a tale that sanitized corporate NASCAR would rather forget about, but with Neal Thompson at the wheel, it makes for wonderful reading.”

—Sharyn McCrumb, author of St. Dale

“Driving with the Devil is a treasure trove of historically relevant information that tracks the history of the American automobile industry, the culture and morality of the broader society, and the motivations and personalities of early stock-car-racing operatives. All of which have inexorably contributed to the foundation and fabric of NASCAR’s brand of stock-car racing as it manifests itself today.”

—Jack Roush, chairman of Roush Racing

“Driving with the Devil is a most impressive piece of work. Most Americans have the vague notion that big-time stock-car racing sprang from moonshine-hauling in the southern Appalachians prior to the Second World War, but here is documented proof that it was that and much more. Neal Thompson’s Driving with the Devil nails it once and for all: a riveting report any student of Americana will cherish. It’s no more about racing than The Old Man and the Sea is about fishing.”

—Paul Hemphill, author of Lovesick Blues: The Life of Hank Williams and Wheels: A Season on NASCAR’s Winston Cup Circuit

"A fascinating and fast-moving account of NASCAR's fledgling days."

–Atlanta Journal Constitution

"There are more divorces, drunks and wrecks than you can shake a checkered flag at...A thoroughly researched account of a 'simpler time' in a sport that has since become a multi-billion dollar business."

–NBC News anchor Brian Williams, in the Wall Street Journal

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Offering an fascinating look at the well-hidden historical connection between whiskey running and stock-car racing, Thompson reveals the dramatic, untold story of Southern moonshiners, their Ford V-8s, and the creation of NASCAR.