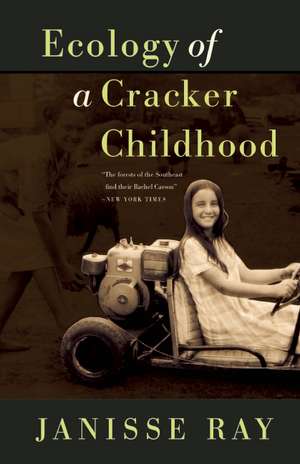

Ecology of a Cracker Childhood

Autor Janisse Rayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2015

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

”A gutsy, wholly original memoir of ragged grace and raw beauty.”

—Kirkus Reviews (STARRED)

From the memories of a childhood marked by extreme poverty, mental illness, and restrictive fundamentalist Christian rules, Janisse Ray crafted a memoir that has inspired thousands to embrace their beginnings, no matter how humble, and fight for the places they love. This edition, published on the fifteenth anniversary of the original publication, updates and contextualizes the story for a new generation and a wider audience desperately searching for stories of empowerment and hope.

Janisse Ray grew up in a junkyard along U.S. Highway 1, hidden from Florida-bound travelers by hulks of old cars. In language at once colloquial, elegiac, and informative, Ray redeems her home and her people, while also cataloging the source of her childhood hope: the Edenic longleaf pine forests, where orchids grow amid wiregrass at the feet of widely spaced, lofty trees. Today, the forests exist in fragments, cherished and threatened, and the South of her youth is gradually being overtaken by golf courses and suburban development. A contemporary classic, Ecology of a Cracker Childhood is a clarion call to protect the cultures and ecologies of every childhood.

—Kirkus Reviews (STARRED)

From the memories of a childhood marked by extreme poverty, mental illness, and restrictive fundamentalist Christian rules, Janisse Ray crafted a memoir that has inspired thousands to embrace their beginnings, no matter how humble, and fight for the places they love. This edition, published on the fifteenth anniversary of the original publication, updates and contextualizes the story for a new generation and a wider audience desperately searching for stories of empowerment and hope.

Janisse Ray grew up in a junkyard along U.S. Highway 1, hidden from Florida-bound travelers by hulks of old cars. In language at once colloquial, elegiac, and informative, Ray redeems her home and her people, while also cataloging the source of her childhood hope: the Edenic longleaf pine forests, where orchids grow amid wiregrass at the feet of widely spaced, lofty trees. Today, the forests exist in fragments, cherished and threatened, and the South of her youth is gradually being overtaken by golf courses and suburban development. A contemporary classic, Ecology of a Cracker Childhood is a clarion call to protect the cultures and ecologies of every childhood.

Preț: 96.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.47€ • 19.28$ • 15.29£

18.47€ • 19.28$ • 15.29£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781571313256

ISBN-10: 1571313257

Pagini: 294

Dimensiuni: 137 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Ediția:Anniversary

Editura: Milkweed Editions

ISBN-10: 1571313257

Pagini: 294

Dimensiuni: 137 x 213 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Ediția:Anniversary

Editura: Milkweed Editions

Recenzii

"The forests of the southeast find their Rachel Carson . . . . In Ecology of a Cracker Childhood, part memoir, part clarion call to save the longleaf pine, she casts a loving but unflinching eye on growing up poor and fundamentalist in southeast Georgia.”

—Anne Raver, New York Times

“Suffused with the same history-haunted sense of loss that imprints so much of the South and its literature. What sets Ecology of a Cracker Childhood apart is the ambitious and arresting mission implied in its title. Ray's passion for preserving this unsung landscape is heartfelt and refreshing.”

—Tony Horwitz, New York Times Book Review

“The gorgeously written Ecology of a Cracker Childhood combines memoir and nature writing in such a way as to take the reader there, to the longleaf pine forests of south Georgia before it was all logged away.”

—Bloomsbury Review, Editor's Favorite Books of 1999

—Anne Raver, New York Times

“Suffused with the same history-haunted sense of loss that imprints so much of the South and its literature. What sets Ecology of a Cracker Childhood apart is the ambitious and arresting mission implied in its title. Ray's passion for preserving this unsung landscape is heartfelt and refreshing.”

—Tony Horwitz, New York Times Book Review

“The gorgeously written Ecology of a Cracker Childhood combines memoir and nature writing in such a way as to take the reader there, to the longleaf pine forests of south Georgia before it was all logged away.”

—Bloomsbury Review, Editor's Favorite Books of 1999

Notă biografică

Writer, naturalist and activist Janisse Ray is the author of six books of literary nonfiction and poetry. She has won the Southern Booksellers Award, the Southeastern Booksellers Award, and an American Book Award. Ray lives and works on a farm in Baxley, GA.

Extras

Introduction

In south Georgia everything is flat and wide. Not empty. My people live among the mobile homes, junked cars, pine plantations, clearcuts, and fields. They live among the lost forests.

The creation ends in south Georgia, at the very edge of the sweet earth. Only the sky, widest of the wide, goes on, flatness against flatness. The sky appears so close that, with a long-enough extension ladder, you think you could touch it, and sometimes you do, when clouds descend in the night to set a fine pelt of dew on the grasses, leaving behind white trails of fog and mist.

At night the stars are thick and bright as a pint jar of fireflies, the moon at full a pearly orb, sailing through them like an egret. By day the sun, close in a paper sky, laps moisture from the land, then gives it back, always an exchange. Even in drought, when each dawn a parched sun cracks against the horizon’s griddle, the air is thick with water.

It is a land of few surprises. It is a land of routine, of cycle, and of constancy. Many a summer afternoon a black cloud builds to the southwest, approaching until you hear thunder and spot lightning, and even then there’s time to clear away tools and bring in the laundry before the first raindrops spatter down. Everything that comes you see coming.

That’s because the land is so wide, so much of it open. It’s wide open, flat as a book, vulnerable as a child. It’s easy to take advantage of, and yet it is also a land of dignity. It has been the way it is for thousands of years, and it is not wont to change.

I was born from people who were born from people who were born from people who were born here. The Crackers crossed the wide Altamaha into what had been Creek territory and settled the vast, fire-loving uplands of the coastal plains of southeast Georgia, surrounded by a singing forest of tall and widely spaced pines whose history they did not know, whose stories were untold. The memory of what they entered is scrawled on my bones, so that I carry the landscape inside like an ache. The story of who I am cannot be severed from the story of the flatwoods.

To find myself among what has been and what remains, I go where my grandmother’s name is inscribed on a clay hill beside my grandfather. The cemetery rests in a sparse stand of remnant longleaf pine, where clumps of wiregrass can still be found. From the grave I can see a hardwood drain, hung with Spanish moss, and beyond to a cypress swamp, and almost to the river, but beyond that, there is only sky.

Chapter One: Child of Pine

When my parents had been married five years and my sister was four, they went out searching among the pinewoods through which the junkyard had begun to spread. It was early February of 1962, and the ewes in the small herd of sheep that kept the grass cropped around the junked cars were dropping lambs.

On this day, Candlemas, with winter half undone, a tormented wind bore down from the north and brought with it a bitter wet cold that cut through my parents’ sweaters and coats and sliced through thin socks, stinging their skin and penetrating to the bone. Tonight the pipes would freeze if the faucets weren’t left dripping, and if the fig tree wasn’t covered with quilts, it would be knocked back to the ground.

It was dark by six, for the days lengthened only by minutes, and my father had gone early to shut up the sheep. Nights he penned them in one end of his shop, a wide, tin-roofed building that smelled both acrid and sweet, a mixture of dry dung, gasoline, hay, and grease. That night when he counted them, one of the ewes was missing. He had bought the sheep to keep weeds and snakes down in the junkyard, so people could get to parts they needed; now he knew all the animals by name and knew also their personalities. Maude was close to her time.

In the hour they had been walking, the temperature had fallen steadily. It would soon be dark. Out of the grayness Mama heard a bleating cry.

“Listen,” she said, touching Daddy’s big arm and stopping so suddenly that shoulder-length curls of dark hair swung across her heart-shaped face. Her eyes were a deep, rich brown, and she cut a fine figure, slim and strong, easy in her body. Her husband was over six feet tall, handsome, his forehead wide and smart, his hair thick and wiry as horsetail.

Again came the cry. It sounded more human than sheep, coming from a clump of palmettos beneath a pine. The sharp-needled fronds of the palmettos stood out emerald against the gray of winter, and the pine needles, so richly brown when first dropped, had faded to dull sienna. Daddy slid his hands—big, rough hands—past the bayonet-tipped palmetto fronds, their fans rattling urgently with his movements, him careful not to rake against saw-blade stems. The weird crying had not stopped. He peered in.

It was a baby. Pine needles cradled a long-limbed newborn child with a duff of dark hair, its face red and puckered. And that was me, his second-born. I came into their lives easy as finding a dark-faced merino with legs yet too wobbly to stand.

My sister had been found in a big cabbage in the garden; a year after me, my brother was discovered under the grapevine, and a year after that, my little brother appeared beside a huckleberry bush. From as early as I could question, I was told this creation story. If they’d said they’d found me in the trunk of a ’52 Ford, it would have been more believable. I was raised on a junkyard on the outskirts of a town called Baxley, the county seat of Appling, in rural south Georgia.

In the 1970 census, Baxley listed 3,500 people and Appling County figured almost 13,000, and a decade later the figures had risen only slightly. Even in 1990 the county’s population was not even 16,000, the town’s a little over 3,800—hardly more than it had been thirty years earlier when I was a girl. Projections for the year 2000 don’t show much of a change. The nearest bigger town was Waycross forty miles south, population 19,000, located on the northern edge of the unvanquished Okefenokee Swamp, and anything that could be called a city lay two or three hours, a hemisphere, away: Jacksonville to the south; Macon to the north; Savannah to the east, on the Atlantic. But those places were outside my knowing, and foreign.

What I knew was a 20’ x 26’, white, clapboard house that sat in the middle of ten brushy acres my father had newly purchased. He’d built the house and strung a hog-wire fence around it, inside which my mother had planted sapling plums and pears and outside which junk was stacked and piled. The house had two small bedrooms opening onto a short hall that joined the living room/kitchen. A thick white sheepskin lay in front of the gas space heater in the hallway, and a little organ that no- body could play sat in the living room. Baby pictures lined the organ. The house’s back steps were concrete blocks that wobbled and grumbled underneath your feet and a screened porch hung off the front door.

Mama tried to keep flowers, beds of four-o’clocks, old maids, and daylilies around the house’s drip line, and mowed the grass regularly. She arranged chairs in the yard among pretty ornaments—a ceramic frog, a tiny wrought-iron tea table. She spray-painted a cast-iron cookstove black and set it up on bricks and hung a wash-pot from a metal frame, and when the sheep got in and ate the flowers, she drove them from the yard with her broom, yelling “shoo, shoo” and “git.”

As soon as I learned to walk, I would wander into the beyond, where the junk began, touching the pint-sized redbud my mother had planted or the hymn of chinaberry that dropped wrinkled and poisonous drupes into the grass. When my mother called, I would crouch in the dirt behind the water pump, perfectly still and quiet, making her search for me. It wasn’t a game.

“Half wild,” she’d murmur. She had to tie bells on my shoes, silver jingle bells that gave away my whereabouts and led her to me.

My hair was long and stringy, snarled at the nape like a rat’s nest, so that Mama, who had brushed it out just that morning, chased me with a hairbrush and pinned it out of my eyes with barrettes. My mouth was dirty as was my dress, and my feet were perpetually dirty, and Mama would pop me in the bathtub and button me into a ruffled dress dotted with flowers she had handsewn on her Singer. But she’d need to peel potatoes for supper or slice a mess of okra, and I would stand looking out the screen door until I worried it into opening, and when she found me, I would again be dirty.

When I was bigger, I could get up into the trees, especially the chinaberry, which had grown quickly and notched after a couple of feet. I would sit in the tree and wait, listening for something—a sound, a resonance—that came from far away, from the past and from the ground. When it came, the sun would hold its breath, the tree would shiver, and I would leap toward the sky, hoping finally for wings, for feathers to tear loose from my shoulders and catch against sweeps of air.

The ground was hard, unyielding, but it wanted me, reaching out its hard, black arms and rising in welcome. I would lift and run along it as fast as I could and think again of soaring, of flying, until I was breathless and oily with sweat, and then I would collapse to the earth.

Premii

- Pat Conroy Southern Book Prize Winner, 2000