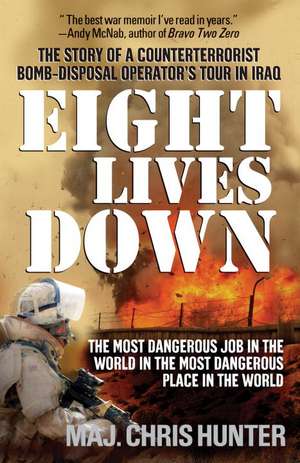

Eight Lives Down: The Most Dangerous Job in the World in the Most Dangerous Place in the World

Autor Chris Hunteren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2009

If fate is against me and I’m killed, so be it, but make it quick and painless. If I’m wounded, don’t let me be crippled. But above all, don’t let me fuck up the task.

So goes the bomb technician’s prayer before every bomb he defuses. For Chris Hunter, it is a prayer he says many times during his four-month tour of Iraq. His is the most dangerous job in the world — to make safe the British sector in Iraq against some of the most hardened and technically advanced terrorists in the world. It is a 24/7 job — in the first two months alone, his team defuses over 45 bombs. And the people they’re up against don’t play by the Geneva Convention. For them, there are no rules, only results — death by any means necessary.

The job of a Bomb Disposal officer is a lonely one. You are alone with the sound of your own breathing and the drumming of your heart in a protective suit in forty-plus degrees of heat. The drawbridge has been pulled up behind you as you advance on your goal. It’s just you and the bomb.

But for Chris Hunter, just when life couldn’t get any more dangerous, the stakes are raised again.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 125.77 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 189

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.07€ • 24.86$ • 20.03£

24.07€ • 24.86$ • 20.03£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553385281

ISBN-10: 0553385283

Pagini: 399

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: DELTA

ISBN-10: 0553385283

Pagini: 399

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: DELTA

Notă biografică

Chris Hunter retired in March 2007 from the Defense Intelligence Staff, where he was the MOD’s senior IED intelligence analyst. He is a former chairman of the Technical Committee of the Institute of Explosives Engineers and continues to work as a counterterrorism consultant. He works regularly with U.S. military and law enforcement personnel, including a number of government agencies and the U.S. Special Forces. He has served on numerous operations in the Balkans, East Africa, Northern Ireland, Colombia, and Afghanistan and was awarded the Queen’s Gallantry Medal for his actions during his tour in Iraq. He lives with his wife and two daughters in the west of England.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Prologue

February 2004

Now I am in my other world. Outside sounds become muted and I am aware only of the sound of my own breathing and the drumming of my heart. This is the moment when I leave everything else behind. The moment when the drawbridge closes behind me and I am truly alone.

The long walk to the target seems to take for ever. I’m carrying 90lb of equipment and wearing a bomb suit that weighs another 80lb. Sweat drips into my eyes and my visor is beginning to mist up in the fearsome tropical heat. The Colombian Jungle Commandos have taken up fire positions in the rainforests and mountains that tower above the ICP. Their job is to stand between me and a sniper’s bullet.

I try not to hold my breath as I take each step, but it isn’t easy. Only 75 metres to go; I’m halfway to the target vehicle. The twinflex firing cable snakes out of my carrying case as I go.

I’m struggling to see. My visor has completely steamed up now. I wipe away the condensation with a cloth. Twenty seconds later it’s steamed up again. The humidity in this place is outrageous.

I go over the threat assessment again in my mind. There are three options. There’s the timed IED, which could go off at IGHT LIVES DOWN any moment. There’s the command initiated device, usually detonated by wire or radio control; it requires an observer, and this terrain offers thousands of potential firing points. I hope to God it’s not RC: the Colombians don’t have any radio jammers, and as I’m here working with them, nor do I. Finally there’s the VO, the booby trap. The Colombian police officers have walked all around the car, so there’s unlikely to be anything buried in the ground, but there’s still every chance of a VO inside it.

So, what is the terrorist trying to achieve? Does he want to get me? Trying to confuse as to intent is a classic Provisional IRA tactic, and I know they’ve been here teaching the FARC boys some new tricks. That’s why I’ve been sent here.

The sweat is pouring off me and my heart’s beating like a drum as I finally reach the target vehicle, one of those 1950s grocery vans you only see in Tintin books. It’s still; eerily silent. There are no tripwires and there’s no disturbed earth, but I can see the improvised mortar through the windscreen. It’s pretty much identical to the last PIRA mortar I saw in Northern Ireland, the barrack buster, a huge projectile which contains as much explosive as your average car bomb. This one’s in a highly volatile state because it’s a misfire – which means it could go live any second. And it’s pointing directly at the village of Espinal.

If it launches now I’ll be engulfed by the blast. As it lands moments later, the fuse will kick into life and the 120kg of ammonium nitrate and sugar explosive will detonate, fragmenting the bomb into hundreds of supersonic pieces of molten metal. All windows within 200 metres will implode, wreaking havoc and causing massive casualties. Hundreds of pieces of shrapnel will smash through unprotected vehicles and structures. Shards of glass will sever limbs, and what little remains of the shredded bodies will almost certainly be destroyed by the napalm fireball that follows.

In May two years ago, three hundred people crowded into a small church in Bojaya, whispering prayers as they hunkered down on the cement floor, seeking sanctuary from the FARC gunfire outside. They thought they would be safe there. They were wrong. A PIRA-designed improvised mortar exploded on the church roof, which collapsed, killing 119. At least forty-five of the victims were children.

I’ve been an operator for seven years and completed three tours in Northern Ireland. I’ve studied the IRA obsessively and I know their tactics inside out. There could be any number of surprises lying in wait. I have to render this device safe. Now.

I begin clearing a safe area around the vehicle. Even if there is no secondary device this time, the bomber will still be watching me. Tracking my procedures and trying to second-guess me the next time we meet. This is only one battle in a very long war.

My body is starting to shake.

I check inside the van for alarm sensors, but there are none. Good. I carry a couple of pieces of ceramic with me – I’ve taken them from a broken spark plug. I throw one at the bottom lefthand corner of the side window and the glass shatters instantly. It’s amazing what tricks you can pick up at school.

I ease my head inside the cab and check out the bomb’s timing and power unit. My most obvious target is its battery pack. If the TPU is the brain of the bomb, the power source is its heart. I edge my EOD disruptor towards it, to get a better shot.

The disruptor is finally good to go. But as I’m about to pull off target and head back to the ICP to take the shot, I notice something else. A length of fishing wire stretches between the underside of the driver’s seat and the door panel. Bastards. They’ve put a victim-operated IED in there too. A secondary. If I’d opened the door instead of leaning through the window it would have been Goodnight Vienna. The FARC boys have listened carefully to everything our Northern Irish friends have taught them.

I have to shatter both circuits. I can’t do them one at a time: if there’s a hidden collapsing circuit, disrupting one device could initiate the other.

I wipe the sweat from my eyes again. I’m going to neutralize them simultaneously.

Chapter One

Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.

T. S. Eliot

Autumn 1981

It’s not who our parents are that counts; it’s the things we remember about them.

My dad’s pulled me out of school as a special treat. We’ve spent the day in the arcade on Brighton pier, playing the fruit machines, and now we’re back at the Old Ship Hotel. This is where we come to have some father and son time when he’s taking a break from the pub he and Mum run in Hertfordshire.

The oak-panelled bedroom is warm and inviting. Its damaskcovered sofas and chairs have a familiar smell; a musty, comforting smell. Flower-patterned curtains hang over the casement. Outside, the rain drums against the window and the waves crash on to the pebbled beach. I sit, spellbound, and stare out across the angry, beguiling ocean. This is my favourite place in the whole world.

I love spending time here with Dad. I’m eight years old and I’ll never get to know him properly, but I already know he’s a EIGHT LIVES DOWN wonderful man. He’s blessed with a mix of compassion and acceptance that makes everybody love him.

Everybody, that is, except Mum. I don’t think she loves him any more. She used to, but now he makes her sad. Not because he’s nasty to her; he adores her. It’s just that he’s always gambling and it makes her cry.

So for now it’s just the two of us, father and son, sitting on the edge of the bed in our hotel room, pitched together like two volumes of the same book.

He looks down at me with a warm smile and puts his arm around my shoulders. I feel safe. I wish every day could be like this.

But as I look up at him, I see that something strange is happening. Beads of sweat are beginning to form on Dad’s forehead. He looks desperate and pained. Tension and fear are etched on his face. His eyes are fixed on the images unfolding on the TV screen in front of him.

Smoke is billowing from bombed-out houses. ARP wardens run down the street, shouting at the mothers, screaming at them to take their children to the shelter, and quickly. At the foot of St Paul’s Cathedral, a man in khaki fatigues is lying in a freezing puddle at the bottom of a shaft. He’s hugging a massive bomb, lying face to face with a monster. The young officer runs his hands cautiously beneath the beast – a thousand kilograms of steel and TNT. He finds a fuse and slowly, carefully, he begins to unscrew it.

But there’s something else. A second fuse. He hesitates . . .

Dad is squeezing my shoulder. I look up at him. His eyes are filled with torment. He’s in agony. ‘Don’t touch it,’ he pleads. ‘Don’t touch the second fuse. It’s rigged.’

He’s no longer sitting with me in this faded Georgian hotel room. He’s back in 1944. He’s somewhere else, a long way from here. His hands are shaking. His breathing is shallow and fast. He’s become part of another world. Another life. His former life.

We’re watching Danger UXB. Only, he’s not just watching it, he’s living it.

Later that night, I can hear Dad praying. ‘Dear God,’ he says, ‘make me the kind of man my son wants me to be.’ Before I go to sleep, I pray that one day I’ll be the kind of man my father is.

February 2004

Now I am in my other world. Outside sounds become muted and I am aware only of the sound of my own breathing and the drumming of my heart. This is the moment when I leave everything else behind. The moment when the drawbridge closes behind me and I am truly alone.

The long walk to the target seems to take for ever. I’m carrying 90lb of equipment and wearing a bomb suit that weighs another 80lb. Sweat drips into my eyes and my visor is beginning to mist up in the fearsome tropical heat. The Colombian Jungle Commandos have taken up fire positions in the rainforests and mountains that tower above the ICP. Their job is to stand between me and a sniper’s bullet.

I try not to hold my breath as I take each step, but it isn’t easy. Only 75 metres to go; I’m halfway to the target vehicle. The twinflex firing cable snakes out of my carrying case as I go.

I’m struggling to see. My visor has completely steamed up now. I wipe away the condensation with a cloth. Twenty seconds later it’s steamed up again. The humidity in this place is outrageous.

I go over the threat assessment again in my mind. There are three options. There’s the timed IED, which could go off at IGHT LIVES DOWN any moment. There’s the command initiated device, usually detonated by wire or radio control; it requires an observer, and this terrain offers thousands of potential firing points. I hope to God it’s not RC: the Colombians don’t have any radio jammers, and as I’m here working with them, nor do I. Finally there’s the VO, the booby trap. The Colombian police officers have walked all around the car, so there’s unlikely to be anything buried in the ground, but there’s still every chance of a VO inside it.

So, what is the terrorist trying to achieve? Does he want to get me? Trying to confuse as to intent is a classic Provisional IRA tactic, and I know they’ve been here teaching the FARC boys some new tricks. That’s why I’ve been sent here.

The sweat is pouring off me and my heart’s beating like a drum as I finally reach the target vehicle, one of those 1950s grocery vans you only see in Tintin books. It’s still; eerily silent. There are no tripwires and there’s no disturbed earth, but I can see the improvised mortar through the windscreen. It’s pretty much identical to the last PIRA mortar I saw in Northern Ireland, the barrack buster, a huge projectile which contains as much explosive as your average car bomb. This one’s in a highly volatile state because it’s a misfire – which means it could go live any second. And it’s pointing directly at the village of Espinal.

If it launches now I’ll be engulfed by the blast. As it lands moments later, the fuse will kick into life and the 120kg of ammonium nitrate and sugar explosive will detonate, fragmenting the bomb into hundreds of supersonic pieces of molten metal. All windows within 200 metres will implode, wreaking havoc and causing massive casualties. Hundreds of pieces of shrapnel will smash through unprotected vehicles and structures. Shards of glass will sever limbs, and what little remains of the shredded bodies will almost certainly be destroyed by the napalm fireball that follows.

In May two years ago, three hundred people crowded into a small church in Bojaya, whispering prayers as they hunkered down on the cement floor, seeking sanctuary from the FARC gunfire outside. They thought they would be safe there. They were wrong. A PIRA-designed improvised mortar exploded on the church roof, which collapsed, killing 119. At least forty-five of the victims were children.

I’ve been an operator for seven years and completed three tours in Northern Ireland. I’ve studied the IRA obsessively and I know their tactics inside out. There could be any number of surprises lying in wait. I have to render this device safe. Now.

I begin clearing a safe area around the vehicle. Even if there is no secondary device this time, the bomber will still be watching me. Tracking my procedures and trying to second-guess me the next time we meet. This is only one battle in a very long war.

My body is starting to shake.

I check inside the van for alarm sensors, but there are none. Good. I carry a couple of pieces of ceramic with me – I’ve taken them from a broken spark plug. I throw one at the bottom lefthand corner of the side window and the glass shatters instantly. It’s amazing what tricks you can pick up at school.

I ease my head inside the cab and check out the bomb’s timing and power unit. My most obvious target is its battery pack. If the TPU is the brain of the bomb, the power source is its heart. I edge my EOD disruptor towards it, to get a better shot.

The disruptor is finally good to go. But as I’m about to pull off target and head back to the ICP to take the shot, I notice something else. A length of fishing wire stretches between the underside of the driver’s seat and the door panel. Bastards. They’ve put a victim-operated IED in there too. A secondary. If I’d opened the door instead of leaning through the window it would have been Goodnight Vienna. The FARC boys have listened carefully to everything our Northern Irish friends have taught them.

I have to shatter both circuits. I can’t do them one at a time: if there’s a hidden collapsing circuit, disrupting one device could initiate the other.

I wipe the sweat from my eyes again. I’m going to neutralize them simultaneously.

Chapter One

Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.

T. S. Eliot

Autumn 1981

It’s not who our parents are that counts; it’s the things we remember about them.

My dad’s pulled me out of school as a special treat. We’ve spent the day in the arcade on Brighton pier, playing the fruit machines, and now we’re back at the Old Ship Hotel. This is where we come to have some father and son time when he’s taking a break from the pub he and Mum run in Hertfordshire.

The oak-panelled bedroom is warm and inviting. Its damaskcovered sofas and chairs have a familiar smell; a musty, comforting smell. Flower-patterned curtains hang over the casement. Outside, the rain drums against the window and the waves crash on to the pebbled beach. I sit, spellbound, and stare out across the angry, beguiling ocean. This is my favourite place in the whole world.

I love spending time here with Dad. I’m eight years old and I’ll never get to know him properly, but I already know he’s a EIGHT LIVES DOWN wonderful man. He’s blessed with a mix of compassion and acceptance that makes everybody love him.

Everybody, that is, except Mum. I don’t think she loves him any more. She used to, but now he makes her sad. Not because he’s nasty to her; he adores her. It’s just that he’s always gambling and it makes her cry.

So for now it’s just the two of us, father and son, sitting on the edge of the bed in our hotel room, pitched together like two volumes of the same book.

He looks down at me with a warm smile and puts his arm around my shoulders. I feel safe. I wish every day could be like this.

But as I look up at him, I see that something strange is happening. Beads of sweat are beginning to form on Dad’s forehead. He looks desperate and pained. Tension and fear are etched on his face. His eyes are fixed on the images unfolding on the TV screen in front of him.

Smoke is billowing from bombed-out houses. ARP wardens run down the street, shouting at the mothers, screaming at them to take their children to the shelter, and quickly. At the foot of St Paul’s Cathedral, a man in khaki fatigues is lying in a freezing puddle at the bottom of a shaft. He’s hugging a massive bomb, lying face to face with a monster. The young officer runs his hands cautiously beneath the beast – a thousand kilograms of steel and TNT. He finds a fuse and slowly, carefully, he begins to unscrew it.

But there’s something else. A second fuse. He hesitates . . .

Dad is squeezing my shoulder. I look up at him. His eyes are filled with torment. He’s in agony. ‘Don’t touch it,’ he pleads. ‘Don’t touch the second fuse. It’s rigged.’

He’s no longer sitting with me in this faded Georgian hotel room. He’s back in 1944. He’s somewhere else, a long way from here. His hands are shaking. His breathing is shallow and fast. He’s become part of another world. Another life. His former life.

We’re watching Danger UXB. Only, he’s not just watching it, he’s living it.

Later that night, I can hear Dad praying. ‘Dear God,’ he says, ‘make me the kind of man my son wants me to be.’ Before I go to sleep, I pray that one day I’ll be the kind of man my father is.

Recenzii

"... packed with such powerful descriptions of coming under fire that at times you begin to imagine you have picked up the script for a Hollywood action movie."

—London Lite

"Will do for Saddam Hussein and George W. Bush what McNab did for Saddam and George Senior"

—Evening Standard

"You're left in awe and wondering if we're paying Our Boys enough for going through this kind of hell. And doubting it."

—Books Sport

From the Hardcover edition.

—London Lite

"Will do for Saddam Hussein and George W. Bush what McNab did for Saddam and George Senior"

—Evening Standard

"You're left in awe and wondering if we're paying Our Boys enough for going through this kind of hell. And doubting it."

—Books Sport

From the Hardcover edition.