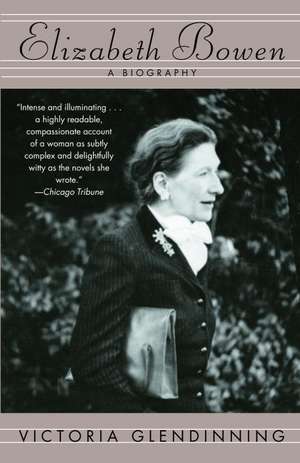

Elizabeth Bowen

Autor Victoria Glendinningen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2006

Taking us from Elizabeth Bowen's ancestral home in Ireland, Bowen’s Court, to Oxford where she met Yeats and Eliot, to her service as an air-raid warden in London during World War II, this penetrating biography lifts the thin veil between Bowen's imaginative world and the complex emotional life that fired her shimmering novels. We see her at elegant parties, where such friends as Virginia Woolf, Eudora Welty, and Evelyn Waugh fell under her spell; in post-war Vienna with Graham Greene; and in war-torn London, where she fell in love with a younger man who was unprepared for life at the pitch she lived it. We see her bound through several affairs to a comfortable marriage, living "life with the lid on." The world of Elizabeth Bowen was akin to that of her novels: no one behaved shockingly, yet the passions that stirred within made her a master of the ultimate suspense of human relationships–the life of the heart.

Preț: 116.64 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 175

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.32€ • 23.22$ • 18.43£

22.32€ • 23.22$ • 18.43£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307277404

ISBN-10: 0307277402

Pagini: 331

Ilustrații: 16 PP B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 0307277402

Pagini: 331

Ilustrații: 16 PP B&W PHOTOGRAPHS

Dimensiuni: 133 x 202 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.34 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Notă biografică

Victoria Glendinning was born in the north of England and read French and Spanish at Oxford. Her first book was A Suppressed Cry, a family memoir about her Quaker great-aunt. She has written biographies of Edith Sitwell (which won the James Tait Black Award and the Duff Cooper Prize), Vita Sackville-West (Whitbread Prize for Biography), Rebecca West, Anthony Trollope (Whitbread Prize for Biography), Jonathan Swift, and Leonard Woolf. She co-edited Mothers and Sons with her son Matthew Glendinning, and has published three novels, The Grown-Ups, Electricity, and Flight. She reviews books for national newspapers and journals, has been a judge of the W. H. Smith Prize and other literary awards, and chair of the judges of the Booker Prize. From 2000-03 she was president of English PEN. She is an Honorary Fellow of Somerville College, Oxford, and was awarded a CBE in 1998.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

Bowen's Court

IN LATE 1959 Cornelius O'Keefe bought Bowen's Court, near Kildorrery, County Cork, from Elizabeth Bowen, the last of the direct line, at a relatively modest price. She hoped that he and his family would inhabit and look after the house. The next year Derek Hill, the painter, asked by Elizabeth to do a painting of Bowen's Court to hang in her new home in England, drove over from Edward Sackville-West's house in County Tipperary. Parking his car by Farahy church, he looked north towards the familiar facade and saw that the roof was off Bowen's Court. By the end of the summer the whole house was demolished.

One can still approach what was Bowen's Court along what was the Lower Avenue. The woods and fine trees around the house are gone; the avenue is rutted by tractors. It may take the stranger a little while to identify the site of the house; it seems strangely small, covered with grass, scrubby bushes, and wild flowers. A line of stable buildings still stands. Walking north from the house-space towards the Ballyhoura mountains, through what was once rockery and laurel-lined woodland, you see that the walls of the three-acre walled garden, too, are still there. Elizabeth wrote of this garden:

A box-edged path runs all the way round, and two paths cross at the sundial in the middle; inside the flower borders, backed by espaliers, are the plots of fruit trees and vegetables, and the glasshouse backs on the sunniest wall. . . . The flowers are, on the whole, old-fashioned--jonquils, polyanthus, parrot tulips, lily o' the valley (grown in cindery beds), voluminous white and crimson peonies, moss roses, mauve-pink cabbage roses, white-pink Celestial roses, borage, sweet pea, snapdragon. . . .1

To go to the garden, walk around in it, select flowers for the house, talk to the gardener, could fill most of a morning for any lady of Bowen's Court. Once Elizabeth's father went there looking for his wife; both vague and dreamy people, they missed each other, and she left, locking the door in the wall, and Henry Bowen was shut in. The walls of the garden enclose nothing at all now.

The third Henry Bowen made Bowen's Court, completing it in 1775. "Since then", wrote Elizabeth, "with a rather alarming sureness, Bowen's Court has made all the succeeding Bowens". After the house was gone, she said that one could not say that the space on which it had stood was empty: "more, as it was--with no house there". And it was, as she said, a clean end.

The little church of the hamlet of Farahy and its glebe lands are carved out of the Bowen's Court demesne. The church is now no longer used. In the little churchyard, against the stone wall that faces where the house was, are the graves of Henry Bowen, his sister Sarah, Elizabeth, his only child, and her husband, Alan Cameron. Not much traffic passes on the Mallow-to-Mitchelstown road, which bounds churchyard and demesne on the south side. It is very quiet. "The churchyard is elegiac", wrote Elizabeth about Farahy. "Trees surrounding it shadow or drip over the graves and evergreens. Catholics as well as Protestants bury here; their dead lie side by side in indisputable peace". From the Bowen's Court side of the churchyard wall a straggling shrub dangles its branches over on to Elizabeth's grave. As late as mid-November it manages a few pink flowers.

Elizabeth inherited Bowen's Court on her father's death in 1930. The house, despite its many perfections, was not comfortable in the modem sense until, after the success of The Heat of the Day in 1949, Elizabeth spent some money on it and put in bathrooms. A little later, planning to live permanently at Bowen's Court instead of being based in England, she did more; the big drawing-room was embellished with curtains made, incredibly, of pink corset-satin: "A very good pink that goes beautifully", C. V. Wedgwood wrote to Jacqueline Hope-Wallace in December, 1953, "the kind of satin that grand shops make corsets and belts of; some local director of Debenhams found they had bales and bales of it left over--actually you would never think of it, but once you have been told you can think of nothing else!"

But even in earlier, more spartan days, Bowen's Court, when Elizabeth was there, was full of people and talk and life. The summer of 1936, for example. On September 25th of that year, Elizabeth wrote to describe her summer to the critic and editor John Hayward, who had written to her from London that "my little world turns very slowly in your absence". Early in August, Lord David Cecil and his wife, Rachel, had been to stay for ten days. "I like Rachel so particularly much, and David's really my oldest, securest friend". The three of them had talked non-stop, she said, "without fatigue, suspicion, exhibitionism, strain, unseemly curiosity or desire to impress". And after the Cecils left more came--the house had been full, which created a problem because although there was lots of space there was not much furniture:

Beds, and even a room in a neighbour's house were borrowed, washstands, blankets (we really did need some new ones), cans, scratchy local bath-towels and four small new teapots bought. Then they all arrived: Roger [Senhouse) and Rosamond [Lehmann] one morning from England, Shaya [Isaiah] Berlin and two student friends [Stuart Hampshire and Con O'Neill] from Killarney that evening, John Summerson, of the Nash book, the morning after, Goronwy Rees two days later. My cousin Noreen Colley was also here. . . . I think of all the guests Roger was really the nicest--in fact I know it--he is so sort of participating, such a support, and makes one feel he really cares for a place itself apart from just the sensation of being there. Shaya was also an angel: I'm very fond of him. . . . Rosamond looked quite lovely, was sweet and I think enjoyed herself. After most of the party had gone, a few other odd people came--one Michael Gilmour, and a nice Irish don who often visits All Souls: Myles Dillon from Dublin.2

When the contents of Bowen's Court were sold at auction in Cork--a two-day sale in April, 1960--the accumulation of many Bowen lifetimes was on offer. As always when old family houses are sold up, the lots ranged from collectors' items to pathetic collections of junk; from gilt mirrors carved with eagles and lions and important pieces in eighteenth-century walnut and mahogany down to waste-paper baskets, lampshades, broken garden tables and "Ewbank carpet cleaner and 2 Hand Bags" (Lot 303). Among it all were "4 China Teapots" sold on the first day with a lustre hot-water jug as Lot I 2: perhaps the four teapots bought specially for the 1936 house-party. And the end of the second day saw the end of the pink drawing-room curtains as Lot 353, promoted for the occasion from corset-satin to "silk damask".

In the beginning, the Bowens were Welsh--ap Owen--from the Gower Peninsula. A Henry Bowen took up arms for the King's party in the Civil War, then switched sides and went to Ireland as a lieutenant-colonel in Cromwell's army. He was a professional soldier, an atheist, a hard man, and was married three times: from the second marriage came the Bowen's Court Bowens.

There was a family myth about the way in which Henry Bowen acquired his property in County Cork. Hawking was his one pleasure, and he had brought with him from Gower a pair of hawks. His sport was disapproved of by the Cromwellians as frivolous and ungodly, but Henry cared for no one, except maybe his hawks. Once when Cromwell sent for him, he turned up with a hawk on his wrist, and played with it while Cromwell was speaking. Cromwell, infuriated, wrung the hawk's neck, and the two men parted in anger. But either Henry turned over a new leaf or Cromwell was impressed by his spirit, for the next thing was that Cromwell proposed to give him as much Irish land as the other hawk could fly over before it came down.

This story was invalidated for Elizabeth by the Buchan family, who told her that a hawk flies straight up and hangs until it drops on its prey. Be that as it may, the story is that "standing near the foot of the Ballyhouras, Colonel Bowen released his hawk, which flew south". And a hawk remained the family crest.

The land over which the hawk had allegedly flown comprised over eight hundred acres, fifty-five of which were designated "unprofitable"--in the terms of the deed of 195, "Mountain and Bogg". Colonel Bowen made his home in a small half-ruined castle near the Farahy stream, where he was joined by his eldest son, John, from Wales.

Colonel Bowen's great-grandson married rich Jane Cole, and the Bowens absorbed not only her lands but, in all succeeding generations, her name: Elizabeth was Elizabeth Dorothea Cole Bowen. And Colonel Bowen's great-great-grandson, a third Henry, was the builder of Bowen's Court. The architect is not known, and no plans or drawings seem to have survived. The house was ten years in the building, was dated 1775, and the family moved in the following year. The money ran out before everything was finished; the Italian plasterers from Cork (trailing plaster roses and basket-work in the drawing-room) were paid off before they had decorated the well ceiling of the great Long Room, which ran the length of the top storey of the house. The north-east corner of the intended square never got built, and the makeshift staircase that joined the first floor with the Long Room remained the only one. Furniture, glass, and silverware Henry had made specially in Cork; so far as design and craftsmanship were concerned, he could not have placed his orders at a better period.

Elizabeth imagined the third Henry and his wife surveying their new home in the moonlight, its newly glazed windows "giving the house the glitter of a superb maniac". Henry said he would like to beget a child to look out of every window in Bowen's Court: in the south facade there were twenty. The Bowens had fourteen children (and seven who did not survive). The third Henry, with insoluble financial and legal problems--the Bowens were compulsive litigants--was the first Bowen, but not the last, nervously to pace the Long Room up and down, up and down.

The year of the United Irishmen's rising, 1798, brought drama to Bowen's Court. A rumour reached the Farahy rectory that the house was going to be attacked. Running across the field, the incumbent warned the Bowens. The household defended itself, and the house, built like a fortress, helped. Shots were fired from inside and out, and in the morning a dead man was found in a pear tree. On this night, a shot was fired into the dining-room. At the house-party in 1936, conversation at dinner one evening about this was shushed by Elizabeth, as one of the maids in the room was from a family that might have been involved in the 1798 raid. (The topic was a mistaken one not because it might reawaken antagonism but because it lacked delicacy.)

During the potato famines of the late 1840s, the current and fifth Mrs. Henry Bowen, a widow, fed the sick and starving from the house; she opened a soup-kitchen in the big stonewalled room that in Elizabeth's day was the laundry. Some died on the way up the grass track from the Farahy gate; a famine pit was dug in a corner of little Farahy churchyard.

Her son Robert Cole Bowen was the first "high-voltage" man, the first big Bowen, in Elizabeth's words, since the housebuilding Henry. When he took over the run-down and impoverished estate, Bowen's Court became a business. Rents and wages came in and went out more regularly than ever before, and the woman he married, Elizabeth Clarke, had both money and gumption. They were Elizabeth's grandparents, though she never knew them.

Robert, a true Victorian, obliterated what Elizabeth called the "unemotional plainness" of Bowen's Court. He filled the house with the glossy, ornate furniture of the 1860s and '70s. The drawing-room was redecorated, and the white, grey, and gold wallpaper he chose remained on its walls afterwards, growing ever more faded, for as long as those walls stood. And he brought in gilt mirrors, gilt pelmets, satin-striped beetlegreen curtains, a patterned carpet. His most revolutionary creation was the Tower, at the back of the house (containing two W.C.s, topped by a tank), which was approached by the back stairs.

Robert Cole Bowen's W.C.s remained the only ones until Elizabeth's improvements in 1949; this was something that visitors such as Blanche Knopf, her American publisher, had to get used to. For Mrs. Knopf--exquisite, Americanly addicted to cleanliness, warmth, and comfort--a stay at bathless Bowen's Court was quite an experience, to which she did her gallant best to respond; she wrote to Elizabeth in August, 1938:

I cannot even begin to tell you what staying at Bowen's Court has meant to me. I have never seen anything quite like it of course, but I never realized how living that way could possibly be.

Possibly, on occasion, it could be rather uncomfortable. Nine years later, Elizabeth told Blanche that the house was in considerably better order since she was there, "though the upstairs rooms are still rather Chas. Addams-ish--I often remind myself of his hostess showing in a guest: 'This is your room. . . . If you want anything, just scream'."

To return to Robert Cole Bowen: he planted screens--thin strips of woodland--to protect the fields, and made the Lower Avenue down to Farahy, to balance the third Henry's Upper Avenue, which ran from the front steps westward to come out on the road to Mallow. And Robert and Elizabeth's eldest child, born in 1862, was Henry Charles Cole Bowen, Elizabeth's father.

He and his eight surviving brothers and sisters had a thin childhood in that overfumished great house. They were thin children; their nursery diet was thin; they grew tall very fast (Elizabeth's father was six feet two inches) and lived "keyed-up": they suffered, Elizabeth thought, from inanition. "Their child life, congested and isolated, their life as Bowens together made a drama from which, as grown-up people, some of them found it hard to emerge. This was Personal Life at its most intense". And they were afraid of their father.

But if Robert Cole Bowen lived at high pressure, his household ran smoothly. The Bowen's Court housekeeper who was still in office in Elizabeth's day, Sarah Barry, came as a very young kitchen maid from Nenagh in those early days (fetched by Robert in a dogcart), and told Elizabeth that "downstairs" life was so harmonious that "you would hardly know who was a Protestant". (The butler was, for one.)

Bowen's Court

IN LATE 1959 Cornelius O'Keefe bought Bowen's Court, near Kildorrery, County Cork, from Elizabeth Bowen, the last of the direct line, at a relatively modest price. She hoped that he and his family would inhabit and look after the house. The next year Derek Hill, the painter, asked by Elizabeth to do a painting of Bowen's Court to hang in her new home in England, drove over from Edward Sackville-West's house in County Tipperary. Parking his car by Farahy church, he looked north towards the familiar facade and saw that the roof was off Bowen's Court. By the end of the summer the whole house was demolished.

One can still approach what was Bowen's Court along what was the Lower Avenue. The woods and fine trees around the house are gone; the avenue is rutted by tractors. It may take the stranger a little while to identify the site of the house; it seems strangely small, covered with grass, scrubby bushes, and wild flowers. A line of stable buildings still stands. Walking north from the house-space towards the Ballyhoura mountains, through what was once rockery and laurel-lined woodland, you see that the walls of the three-acre walled garden, too, are still there. Elizabeth wrote of this garden:

A box-edged path runs all the way round, and two paths cross at the sundial in the middle; inside the flower borders, backed by espaliers, are the plots of fruit trees and vegetables, and the glasshouse backs on the sunniest wall. . . . The flowers are, on the whole, old-fashioned--jonquils, polyanthus, parrot tulips, lily o' the valley (grown in cindery beds), voluminous white and crimson peonies, moss roses, mauve-pink cabbage roses, white-pink Celestial roses, borage, sweet pea, snapdragon. . . .1

To go to the garden, walk around in it, select flowers for the house, talk to the gardener, could fill most of a morning for any lady of Bowen's Court. Once Elizabeth's father went there looking for his wife; both vague and dreamy people, they missed each other, and she left, locking the door in the wall, and Henry Bowen was shut in. The walls of the garden enclose nothing at all now.

The third Henry Bowen made Bowen's Court, completing it in 1775. "Since then", wrote Elizabeth, "with a rather alarming sureness, Bowen's Court has made all the succeeding Bowens". After the house was gone, she said that one could not say that the space on which it had stood was empty: "more, as it was--with no house there". And it was, as she said, a clean end.

The little church of the hamlet of Farahy and its glebe lands are carved out of the Bowen's Court demesne. The church is now no longer used. In the little churchyard, against the stone wall that faces where the house was, are the graves of Henry Bowen, his sister Sarah, Elizabeth, his only child, and her husband, Alan Cameron. Not much traffic passes on the Mallow-to-Mitchelstown road, which bounds churchyard and demesne on the south side. It is very quiet. "The churchyard is elegiac", wrote Elizabeth about Farahy. "Trees surrounding it shadow or drip over the graves and evergreens. Catholics as well as Protestants bury here; their dead lie side by side in indisputable peace". From the Bowen's Court side of the churchyard wall a straggling shrub dangles its branches over on to Elizabeth's grave. As late as mid-November it manages a few pink flowers.

Elizabeth inherited Bowen's Court on her father's death in 1930. The house, despite its many perfections, was not comfortable in the modem sense until, after the success of The Heat of the Day in 1949, Elizabeth spent some money on it and put in bathrooms. A little later, planning to live permanently at Bowen's Court instead of being based in England, she did more; the big drawing-room was embellished with curtains made, incredibly, of pink corset-satin: "A very good pink that goes beautifully", C. V. Wedgwood wrote to Jacqueline Hope-Wallace in December, 1953, "the kind of satin that grand shops make corsets and belts of; some local director of Debenhams found they had bales and bales of it left over--actually you would never think of it, but once you have been told you can think of nothing else!"

But even in earlier, more spartan days, Bowen's Court, when Elizabeth was there, was full of people and talk and life. The summer of 1936, for example. On September 25th of that year, Elizabeth wrote to describe her summer to the critic and editor John Hayward, who had written to her from London that "my little world turns very slowly in your absence". Early in August, Lord David Cecil and his wife, Rachel, had been to stay for ten days. "I like Rachel so particularly much, and David's really my oldest, securest friend". The three of them had talked non-stop, she said, "without fatigue, suspicion, exhibitionism, strain, unseemly curiosity or desire to impress". And after the Cecils left more came--the house had been full, which created a problem because although there was lots of space there was not much furniture:

Beds, and even a room in a neighbour's house were borrowed, washstands, blankets (we really did need some new ones), cans, scratchy local bath-towels and four small new teapots bought. Then they all arrived: Roger [Senhouse) and Rosamond [Lehmann] one morning from England, Shaya [Isaiah] Berlin and two student friends [Stuart Hampshire and Con O'Neill] from Killarney that evening, John Summerson, of the Nash book, the morning after, Goronwy Rees two days later. My cousin Noreen Colley was also here. . . . I think of all the guests Roger was really the nicest--in fact I know it--he is so sort of participating, such a support, and makes one feel he really cares for a place itself apart from just the sensation of being there. Shaya was also an angel: I'm very fond of him. . . . Rosamond looked quite lovely, was sweet and I think enjoyed herself. After most of the party had gone, a few other odd people came--one Michael Gilmour, and a nice Irish don who often visits All Souls: Myles Dillon from Dublin.2

When the contents of Bowen's Court were sold at auction in Cork--a two-day sale in April, 1960--the accumulation of many Bowen lifetimes was on offer. As always when old family houses are sold up, the lots ranged from collectors' items to pathetic collections of junk; from gilt mirrors carved with eagles and lions and important pieces in eighteenth-century walnut and mahogany down to waste-paper baskets, lampshades, broken garden tables and "Ewbank carpet cleaner and 2 Hand Bags" (Lot 303). Among it all were "4 China Teapots" sold on the first day with a lustre hot-water jug as Lot I 2: perhaps the four teapots bought specially for the 1936 house-party. And the end of the second day saw the end of the pink drawing-room curtains as Lot 353, promoted for the occasion from corset-satin to "silk damask".

In the beginning, the Bowens were Welsh--ap Owen--from the Gower Peninsula. A Henry Bowen took up arms for the King's party in the Civil War, then switched sides and went to Ireland as a lieutenant-colonel in Cromwell's army. He was a professional soldier, an atheist, a hard man, and was married three times: from the second marriage came the Bowen's Court Bowens.

There was a family myth about the way in which Henry Bowen acquired his property in County Cork. Hawking was his one pleasure, and he had brought with him from Gower a pair of hawks. His sport was disapproved of by the Cromwellians as frivolous and ungodly, but Henry cared for no one, except maybe his hawks. Once when Cromwell sent for him, he turned up with a hawk on his wrist, and played with it while Cromwell was speaking. Cromwell, infuriated, wrung the hawk's neck, and the two men parted in anger. But either Henry turned over a new leaf or Cromwell was impressed by his spirit, for the next thing was that Cromwell proposed to give him as much Irish land as the other hawk could fly over before it came down.

This story was invalidated for Elizabeth by the Buchan family, who told her that a hawk flies straight up and hangs until it drops on its prey. Be that as it may, the story is that "standing near the foot of the Ballyhouras, Colonel Bowen released his hawk, which flew south". And a hawk remained the family crest.

The land over which the hawk had allegedly flown comprised over eight hundred acres, fifty-five of which were designated "unprofitable"--in the terms of the deed of 195, "Mountain and Bogg". Colonel Bowen made his home in a small half-ruined castle near the Farahy stream, where he was joined by his eldest son, John, from Wales.

Colonel Bowen's great-grandson married rich Jane Cole, and the Bowens absorbed not only her lands but, in all succeeding generations, her name: Elizabeth was Elizabeth Dorothea Cole Bowen. And Colonel Bowen's great-great-grandson, a third Henry, was the builder of Bowen's Court. The architect is not known, and no plans or drawings seem to have survived. The house was ten years in the building, was dated 1775, and the family moved in the following year. The money ran out before everything was finished; the Italian plasterers from Cork (trailing plaster roses and basket-work in the drawing-room) were paid off before they had decorated the well ceiling of the great Long Room, which ran the length of the top storey of the house. The north-east corner of the intended square never got built, and the makeshift staircase that joined the first floor with the Long Room remained the only one. Furniture, glass, and silverware Henry had made specially in Cork; so far as design and craftsmanship were concerned, he could not have placed his orders at a better period.

Elizabeth imagined the third Henry and his wife surveying their new home in the moonlight, its newly glazed windows "giving the house the glitter of a superb maniac". Henry said he would like to beget a child to look out of every window in Bowen's Court: in the south facade there were twenty. The Bowens had fourteen children (and seven who did not survive). The third Henry, with insoluble financial and legal problems--the Bowens were compulsive litigants--was the first Bowen, but not the last, nervously to pace the Long Room up and down, up and down.

The year of the United Irishmen's rising, 1798, brought drama to Bowen's Court. A rumour reached the Farahy rectory that the house was going to be attacked. Running across the field, the incumbent warned the Bowens. The household defended itself, and the house, built like a fortress, helped. Shots were fired from inside and out, and in the morning a dead man was found in a pear tree. On this night, a shot was fired into the dining-room. At the house-party in 1936, conversation at dinner one evening about this was shushed by Elizabeth, as one of the maids in the room was from a family that might have been involved in the 1798 raid. (The topic was a mistaken one not because it might reawaken antagonism but because it lacked delicacy.)

During the potato famines of the late 1840s, the current and fifth Mrs. Henry Bowen, a widow, fed the sick and starving from the house; she opened a soup-kitchen in the big stonewalled room that in Elizabeth's day was the laundry. Some died on the way up the grass track from the Farahy gate; a famine pit was dug in a corner of little Farahy churchyard.

Her son Robert Cole Bowen was the first "high-voltage" man, the first big Bowen, in Elizabeth's words, since the housebuilding Henry. When he took over the run-down and impoverished estate, Bowen's Court became a business. Rents and wages came in and went out more regularly than ever before, and the woman he married, Elizabeth Clarke, had both money and gumption. They were Elizabeth's grandparents, though she never knew them.

Robert, a true Victorian, obliterated what Elizabeth called the "unemotional plainness" of Bowen's Court. He filled the house with the glossy, ornate furniture of the 1860s and '70s. The drawing-room was redecorated, and the white, grey, and gold wallpaper he chose remained on its walls afterwards, growing ever more faded, for as long as those walls stood. And he brought in gilt mirrors, gilt pelmets, satin-striped beetlegreen curtains, a patterned carpet. His most revolutionary creation was the Tower, at the back of the house (containing two W.C.s, topped by a tank), which was approached by the back stairs.

Robert Cole Bowen's W.C.s remained the only ones until Elizabeth's improvements in 1949; this was something that visitors such as Blanche Knopf, her American publisher, had to get used to. For Mrs. Knopf--exquisite, Americanly addicted to cleanliness, warmth, and comfort--a stay at bathless Bowen's Court was quite an experience, to which she did her gallant best to respond; she wrote to Elizabeth in August, 1938:

I cannot even begin to tell you what staying at Bowen's Court has meant to me. I have never seen anything quite like it of course, but I never realized how living that way could possibly be.

Possibly, on occasion, it could be rather uncomfortable. Nine years later, Elizabeth told Blanche that the house was in considerably better order since she was there, "though the upstairs rooms are still rather Chas. Addams-ish--I often remind myself of his hostess showing in a guest: 'This is your room. . . . If you want anything, just scream'."

To return to Robert Cole Bowen: he planted screens--thin strips of woodland--to protect the fields, and made the Lower Avenue down to Farahy, to balance the third Henry's Upper Avenue, which ran from the front steps westward to come out on the road to Mallow. And Robert and Elizabeth's eldest child, born in 1862, was Henry Charles Cole Bowen, Elizabeth's father.

He and his eight surviving brothers and sisters had a thin childhood in that overfumished great house. They were thin children; their nursery diet was thin; they grew tall very fast (Elizabeth's father was six feet two inches) and lived "keyed-up": they suffered, Elizabeth thought, from inanition. "Their child life, congested and isolated, their life as Bowens together made a drama from which, as grown-up people, some of them found it hard to emerge. This was Personal Life at its most intense". And they were afraid of their father.

But if Robert Cole Bowen lived at high pressure, his household ran smoothly. The Bowen's Court housekeeper who was still in office in Elizabeth's day, Sarah Barry, came as a very young kitchen maid from Nenagh in those early days (fetched by Robert in a dogcart), and told Elizabeth that "downstairs" life was so harmonious that "you would hardly know who was a Protestant". (The butler was, for one.)

Recenzii

"Intense and illuminating...a highly readable, compassionate account of a woman as subtly complex and delightfully witty as the novels she wrote." —Chicago Tribune

"As a complex and compelling personality, Miss Bowen comes very much to life on these pages...entirely absorbing." —The New York Times

"As a complex and compelling personality, Miss Bowen comes very much to life on these pages...entirely absorbing." —The New York Times