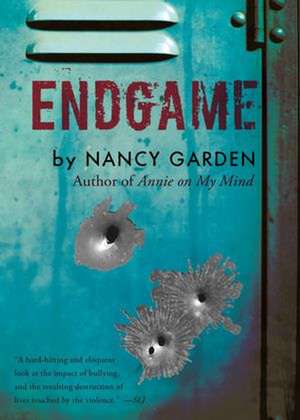

Endgame

Autor Nancy Gardenen Paperback – 5 noi 2012 – vârsta de la 12 ani

New town, new school, new start. That’s what fourteen-year-old Gray Wilton believes. But it doesn’t take long for him to realize that there are bullies in every school, and he’s always their punching bag. Their abuses escalate until Gray feels trapped and alone. He has no power at all until he enters the halls of Greenford High School with his father’s semiautomatic in hand. Nancy Garden deftly explores the cruelty of bullying and its devastating effects. In this brutal, heartbreaking story, a school shooting shatters lives on both sides of the gun.

Preț: 96.68 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 145

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.50€ • 19.31$ • 15.31£

18.50€ • 19.31$ • 15.31£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780152063771

ISBN-10: 0152063773

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 127 x 178 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: HMH Books

Colecția Hmh Books for Young Readers

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0152063773

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 127 x 178 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: HMH Books

Colecția Hmh Books for Young Readers

Locul publicării:United States

Notă biografică

Nancy

Gardenis

the

award-winning

author

ofAnnie

on

My

Mind,one

of

the

first

young

adult

novels

to

dramatize

a

lesbian

relationship.

She

currently

lives

in

Massachusetts.

Visit

her

atwww.nancygarden.com.

Extras

Falco:

Sam

Falco

interviewing

Grayson

Wilton,

age

fifteen,

at

South

Juvenile

Detention

Center,

case

number

9872.

Gray,

I’ve

told

you

about

the

tape

recorder.

Am

I

right

that

you

have

no

objections

to

it?

.

.

.

Gray?

Gray: Yeah, okay. I guess. I don’t really care.

Falco: Okay. Thank you. So—I guess we might as well get started. Let’s see—okay, when did you move to Connecticut?

Gray: Last summer. August? Around the middle.

Falco: Go on.

Gray: What? Go on where? With what?

Falco: Well—how about your new place? What’s

the first thing you remember doing there? Unpacking? Exploring?

Gray: No. Mowing. I remember cutting the grass. Yeah, and counting . . .

One hundred and fifty-three steps, big ones, from the house to the street, and one hundred and seventy-five from side to side. That was our front lawn in Greenford, Connecticut, which my mother made me mow almost as soon as we moved into our new house. I guess that makes it twenty-six thousand, seven hundred and seventy-five square steps big.

Mowing’s not too bad of a job, so I didn’t mind much, even though I was in a sort of bad mood about moving. Hopeful, too, though.

I stopped counting and made up one of those whatchamacallits, you know, mantras? Gonna be better, gonna be better here; gonna be better, gonna be better here. That got pretty lame, though, so I stopped and tried to blank my mind, but now it kept wanting to go mow, mow, mow your—what? I couldn’t think of what. Not boat. Grass? Yard?

By the time I’d run out of mind games and was pretty sweaty, this girl came over from next door carrying a dish, like a one-girl Welcome Wagon. She was like, “Hi, I’m Lindsay Maller, from next door. My mom made a casserole for you guys. You know, welcome to the neighborhood, welcome to Greenford, Connecticut, too.”

I knew she was trying to make conversation, but I was worried she’d be able to smell me from ten feet—no, wrong, back to counting: ten steps—away, so I just told her my mom was inside and went back to counting and mowing. By the time I was done I was really thirsty, so I went in to get a drink and I saw the girl was sitting at the kitchen table with my brother, Peter. Mom was handing out Cokes and I wanted to get one, too, but I was still sweaty and the girl was right there. I was trying to decide whether to go in anyway or get some water from the bathroom when I heard Mom say, “So, you must be—what? Sixteen?”

“Yes, sixteen,” the girl said.

“Peter’s seventeen and Grayson—Gray, my other son—is fourteen. I don’t suppose you have a little brother?”

“No, sorry,” she said. “A sister, Joni. She’s eight.”

“Too young for Gray,” Mom said, “even though he’s small and young for his age.” She dropped her voice almost like she knew I was there. “You know—immature.”

Well, how could I go in then? I could feel my face getting red and my sort-of bad mood getting really bad. I forgot about being thirsty, and I really wanted to bang on my drums, which is what sometimes helped when I was mad. But my drums weren’t set up yet and I couldn’t get at them anyway, so I ran back outside, shoved the lawn mower into the garage, and rummaged in the U-Haul for my target and bow and arrows, thinking, Damn, why’d she say that about me being small and immature? Can’t my own mother tell I’m not done growing? Jemmy—he was my best friend back in Massachusetts—grew a lot that year all of a sudden, and when we moved, his mom was still kidding about how she had to keep buying him new jeans.

Then I said to myself, Chill, Gray. Gonna be better, gonna be better here, remember? Hey, maybe my zits might even go away this year.

Yeah, in my dreams.

Dad never did really come right out and tell the truth about why we had to move to Connecticut. What he said was it’d be an easy commute into New York City to his new job. But he didn’t have to get a new job. There wasn’t anything wrong with his old one. He’s some kind of supervisor at a business-machine company. That’s what he did at his old job, too, so what’s the big difference? “More money, guys” was what he told us, though, and he gave my brother, Peter, one of his chip-off-the-old-block punches. “More money for college for my Number-OneSon.”

Maybe you noticed that he didn’t say anything about his Number-Two Son. See, I was the real reason for the new job and the move, and the reason both Mom and Dad seemed to be waiting for me to screw up again, and the reason why we never had any fun as a family, all four of us, anymore.

We used to do stuff on weekends, like a normal family. The zoo, hikes, museums. We even went to Disney World when I was little. That was fun. Neat rides and stuff. And we once all stood outside the fence at this little racetrack and watched ten races from there because kids weren’t allowed inside where there was betting going on. But we bet each other, and I won a dollar.

No more, though.

But things’ll be better here, I told myself. I’m gonna change. We all are. Mom’s gonna stand up to Dad more, and Dad’s gonna stop getting on my case, and Perfect Peter’s gonna make a mistake once in a while, and I’m gonna stop making mistakes. Change for the better, you know?

Yeah.

I tried to feel it in my—bones, I guess. Isn’t that where people are supposed to feel things like that?

Like that’s really possible!

I’d found my archery stuff by then, and my dog, Barker—he was a brown and white springer spaniel—was looking at me from where he was sitting in the driveway. He stretched his front legs out and sent his rump up like dogs do when they want to play.

“Come watch me shoot,” I told him. I lugged the target to the backyard and set it up. “Let’s go get us some bull’s-eyes.”

I did get some, too, and Barker watched, grinning like he always did. He’d tried to chase my arrows a couple of times back when he was a puppy, but as soon as he saw that they pretty much always went into the target, he stopped. And this time was no different. By the time Dad drove in, back from whatever had sent him to the hardware store, there was a whole cluster of arrows sticking out of the center of the target. I felt better, too.

“You oughta move that target back some, Gray,” Dad called almost before he was all the way out of the car. “Make it harder for yourself.”

That was it. Nothing about the bull’s-eyes. No “Nice shooting” or “Way to go, kid,” like he used to say. As soon as he’d told me to move the target, Dad lumbered into the house, carrying a paper bag of whatever he’d dashed out for.

Okay, so then my mantra about things getting better did a nosedive out of my head and I slammed my hand against the target, nearly knocking it over and making Barker look up from the sun patch he was snoozing in. As I started to yank the arrows out I heard Peter yell, “Hey, don’t wreck it!”

My big brother—people say he looks like Dad and I look like Mom—came out the back door, gave Barker a pat on the head as he passed, and then slapped me on the back. He’s like, “Wow,” as he examined what was left of the arrow cluster. “Have to start calling you Robin Hood.” He pulled out the rest of the arrows and handed them to me. “How about a run? Mom says we’re going out for dinner. We’ve got time to explore. Although,” he said, sort of wagging his head at the street, “it looks to me as if there’s not a whole lot to see.” He slapped me on the back again. “C’mon anyway. Let’s go change.”

Copyright © 2006 by Nancy Garden

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should

be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Gray: Yeah, okay. I guess. I don’t really care.

Falco: Okay. Thank you. So—I guess we might as well get started. Let’s see—okay, when did you move to Connecticut?

Gray: Last summer. August? Around the middle.

Falco: Go on.

Gray: What? Go on where? With what?

Falco: Well—how about your new place? What’s

the first thing you remember doing there? Unpacking? Exploring?

Gray: No. Mowing. I remember cutting the grass. Yeah, and counting . . .

One hundred and fifty-three steps, big ones, from the house to the street, and one hundred and seventy-five from side to side. That was our front lawn in Greenford, Connecticut, which my mother made me mow almost as soon as we moved into our new house. I guess that makes it twenty-six thousand, seven hundred and seventy-five square steps big.

Mowing’s not too bad of a job, so I didn’t mind much, even though I was in a sort of bad mood about moving. Hopeful, too, though.

I stopped counting and made up one of those whatchamacallits, you know, mantras? Gonna be better, gonna be better here; gonna be better, gonna be better here. That got pretty lame, though, so I stopped and tried to blank my mind, but now it kept wanting to go mow, mow, mow your—what? I couldn’t think of what. Not boat. Grass? Yard?

By the time I’d run out of mind games and was pretty sweaty, this girl came over from next door carrying a dish, like a one-girl Welcome Wagon. She was like, “Hi, I’m Lindsay Maller, from next door. My mom made a casserole for you guys. You know, welcome to the neighborhood, welcome to Greenford, Connecticut, too.”

I knew she was trying to make conversation, but I was worried she’d be able to smell me from ten feet—no, wrong, back to counting: ten steps—away, so I just told her my mom was inside and went back to counting and mowing. By the time I was done I was really thirsty, so I went in to get a drink and I saw the girl was sitting at the kitchen table with my brother, Peter. Mom was handing out Cokes and I wanted to get one, too, but I was still sweaty and the girl was right there. I was trying to decide whether to go in anyway or get some water from the bathroom when I heard Mom say, “So, you must be—what? Sixteen?”

“Yes, sixteen,” the girl said.

“Peter’s seventeen and Grayson—Gray, my other son—is fourteen. I don’t suppose you have a little brother?”

“No, sorry,” she said. “A sister, Joni. She’s eight.”

“Too young for Gray,” Mom said, “even though he’s small and young for his age.” She dropped her voice almost like she knew I was there. “You know—immature.”

Well, how could I go in then? I could feel my face getting red and my sort-of bad mood getting really bad. I forgot about being thirsty, and I really wanted to bang on my drums, which is what sometimes helped when I was mad. But my drums weren’t set up yet and I couldn’t get at them anyway, so I ran back outside, shoved the lawn mower into the garage, and rummaged in the U-Haul for my target and bow and arrows, thinking, Damn, why’d she say that about me being small and immature? Can’t my own mother tell I’m not done growing? Jemmy—he was my best friend back in Massachusetts—grew a lot that year all of a sudden, and when we moved, his mom was still kidding about how she had to keep buying him new jeans.

Then I said to myself, Chill, Gray. Gonna be better, gonna be better here, remember? Hey, maybe my zits might even go away this year.

Yeah, in my dreams.

Dad never did really come right out and tell the truth about why we had to move to Connecticut. What he said was it’d be an easy commute into New York City to his new job. But he didn’t have to get a new job. There wasn’t anything wrong with his old one. He’s some kind of supervisor at a business-machine company. That’s what he did at his old job, too, so what’s the big difference? “More money, guys” was what he told us, though, and he gave my brother, Peter, one of his chip-off-the-old-block punches. “More money for college for my Number-OneSon.”

Maybe you noticed that he didn’t say anything about his Number-Two Son. See, I was the real reason for the new job and the move, and the reason both Mom and Dad seemed to be waiting for me to screw up again, and the reason why we never had any fun as a family, all four of us, anymore.

We used to do stuff on weekends, like a normal family. The zoo, hikes, museums. We even went to Disney World when I was little. That was fun. Neat rides and stuff. And we once all stood outside the fence at this little racetrack and watched ten races from there because kids weren’t allowed inside where there was betting going on. But we bet each other, and I won a dollar.

No more, though.

But things’ll be better here, I told myself. I’m gonna change. We all are. Mom’s gonna stand up to Dad more, and Dad’s gonna stop getting on my case, and Perfect Peter’s gonna make a mistake once in a while, and I’m gonna stop making mistakes. Change for the better, you know?

Yeah.

I tried to feel it in my—bones, I guess. Isn’t that where people are supposed to feel things like that?

Like that’s really possible!

I’d found my archery stuff by then, and my dog, Barker—he was a brown and white springer spaniel—was looking at me from where he was sitting in the driveway. He stretched his front legs out and sent his rump up like dogs do when they want to play.

“Come watch me shoot,” I told him. I lugged the target to the backyard and set it up. “Let’s go get us some bull’s-eyes.”

I did get some, too, and Barker watched, grinning like he always did. He’d tried to chase my arrows a couple of times back when he was a puppy, but as soon as he saw that they pretty much always went into the target, he stopped. And this time was no different. By the time Dad drove in, back from whatever had sent him to the hardware store, there was a whole cluster of arrows sticking out of the center of the target. I felt better, too.

“You oughta move that target back some, Gray,” Dad called almost before he was all the way out of the car. “Make it harder for yourself.”

That was it. Nothing about the bull’s-eyes. No “Nice shooting” or “Way to go, kid,” like he used to say. As soon as he’d told me to move the target, Dad lumbered into the house, carrying a paper bag of whatever he’d dashed out for.

Okay, so then my mantra about things getting better did a nosedive out of my head and I slammed my hand against the target, nearly knocking it over and making Barker look up from the sun patch he was snoozing in. As I started to yank the arrows out I heard Peter yell, “Hey, don’t wreck it!”

My big brother—people say he looks like Dad and I look like Mom—came out the back door, gave Barker a pat on the head as he passed, and then slapped me on the back. He’s like, “Wow,” as he examined what was left of the arrow cluster. “Have to start calling you Robin Hood.” He pulled out the rest of the arrows and handed them to me. “How about a run? Mom says we’re going out for dinner. We’ve got time to explore. Although,” he said, sort of wagging his head at the street, “it looks to me as if there’s not a whole lot to see.” He slapped me on the back again. “C’mon anyway. Let’s go change.”

Copyright © 2006 by Nancy Garden

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including

photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should

be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Descriere

In

this

devastating

novel,

a

school

shooting

shatters

lives

on

both

sides

of

the

gun. Told

from

the

point

of

view

of

of

fourteen-year-old

Gray

Wilton,

who

killed

four students

at

his

high

school, as

he awaits

his

murder

trial.