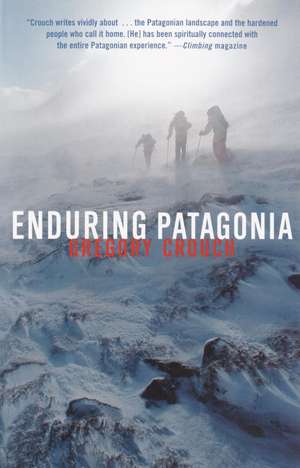

Enduring Patagonia

Autor Gregory Crouchen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2002

Gregory Crouch is one such pilgrim. In seven expeditions to this windswept edge of the Southern Hemisphere, he has braved weather, gravity, fear, and doubt to try himself in the alpine crucible of Patagonia. Crouch has had several notable successes, including the first winter ascent of the legendary Cerro Torre's West Face, to go along with his many spectacular failures. In language both stirring and lyrical, he evokes the perils of every handhold, perils that illustrate the crucial balance between physical danger and mental agility that allows for the most important part of any climb, which is not reaching the summit, but getting down alive.

Crouch reveals the flip side of cutting-edge alpinism: the stunning variety of menial labor one must often perform to afford the next expedition. From building sewer systems during a bitter Colorado winter to washing the plastic balls in McDonalds' playgrounds, Crouch's dedication to the alpine craft has seen him through as many low moments as high summits. He recounts, too, the riotous celebrations of successful climbs, the numbing boredom of forced encampments, and the quiet pride that comes from knowing that one has performed well and bravely, even in failure. Included are more than two dozen color photographs that capture the many moods of this land, from the sublime beauty of the mountains at sunrise to the unrelenting fury of its storms.

Enduring Patagonia is a breathtaking odyssey through one of the worldís last wild places, a land that requires great sacrifice but offers great rewards to those who dare to challenge it.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 98.79 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 148

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.91€ • 19.49$ • 15.95£

18.91€ • 19.49$ • 15.95£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 06-20 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375761287

ISBN-10: 0375761284

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 16-PP B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 206 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0375761284

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: 16-PP B&W INSERT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 206 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Recenzii

"An otherworldly range of mountains exists in Patagonia, at the southern end of the Americas. It is a sublime range, where ice and granite soar with a dancer's grace. From the mountains' feet tumble glaciers and dark forests of beech. The summits float in the southern sky, impossibly remote. Climbers who gaze upon these wonders ache to unlock their secrets. Hard, steep, massive, these might be our planet?s most perfect mountains."

--from Enduring Patagonia

From the Hardcover edition.

--from Enduring Patagonia

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

Gregory Crouch grew up in Goleta, California, where he now lives with his wife, DeAnne, and their son, Ryan. He has made more than a dozen climbing expeditions on four continents, most notably in Alaska and Patagonia, and his work has appeared in National Geographic, Islands, Backpacker, Climbing, and Rock & Ice.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

MY PATAGONIA

An otherworldly range of mountains exists in Patagonia, at the southern end of the Americas. It is a sublime range, where ice and granite soar with a dancer’s grace. From the mountains’ feet tumble glaciers and dark forests of beech. The summits float in the southern sky, impossibly remote. Climbers who gaze upon these wonders ache to unlock their secrets. Hard, steep, massive, these might be our planet’s most perfect mountains. To court these summits is to graft fear to your heart, for all is not idyllic beauty among the great peaks of Patagonia. They stand squarely athwart what sailors refer to as the “roaring forties” and “furious fifties”—that region of the Southern Hemisphere between 40° and 60° south latitude known for ferocious wind and storm. The violent weather spawned over the great south sea charges through the Patagonian Andes with gale-force wind, roaring cloud, and stinging snow. Buried like a rapier deep into the heart of the southern ocean, Patagonia is a land trapped between angry torrents of sea and sky.

The horrendous weather more than makes up for the fact that the mountains of Patagonia do not count extreme altitude as a weapon. Altitude is only one aspect of climbing difficulty. The enormous walls of Patagonia demand fast, efficient, and expert practice of every climbing technique. Wealthy dilettantes cannot buy their way onto these exclusive summits. Only years of dedication to the alpine trade earn a climber the right to gain a Patagonian summit.

Cerro Fitzroy and Cerro Torre are the two crown jewels of the range. Seen from across the wind-swept scrub of the steppes to the east, they are the two crux battlements in the long Andean rampart. Far outdoing the Great Pyramids, Fitzroy’s stone bulk towers 10,000 feet over the arid plains and dominates the landscape like a barbarian king. Beside and a bit behind the king rises Cerro Torre, his royal consort, a graceful obelisk: tall, slender, vertiginous, elusive, hers the very form of alpine perfection. Although Fitzroy is a few hundred feet taller, Cerro Torre exceeds the king in every aspect except size—in difficulty, in threat, in promise, in beauty, in subtlety, and in the savageness of her fury. Cerro Fitzroy and Cerro Torre shoulder the sky like titans.

Cerro Torre stands at the left end of a line of towers, all divided from Fitzroy and his satellites by a deep valley and a flowing glacier. Fitzroy’s half-dozen satellites form a horseshoe to the left and right of the king. Anywhere else, the peaks that flank Fitzroy and Cerro Torre would be centerpiece summits; here in Patagonia they are the palace guard.

Beyond the mountains to the west lies the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap. The ice cap runs north-south like a long irregular cigar, bounded on one side by the front range of the Andes, and on the other by the Pacific Ocean. At its widest point, twenty-five miles north of the Fitzroy massif, the ice cap is almost sixty miles across. At its narrowest, sixty miles south of Fitzroy, less than ten miles of ice separate the Pacific Ocean in Fiordo Peel from fresh waters that flow into the Brazo Mayor (the major arm) of Lago Argentino. From north to south the ice cap is 225 miles long, and without counting the many glaciers that drain it, the surface of the ice cap measures more than 5,000 square miles. It is our world’s largest nonpolar expanse of ice and one of the least knowable landscapes on earth. From no point in the settled world can one get a true impression of the ice cap, for the Andes block the view of it from the inhabited desert to the east. There are places from which we can observe the glaciers that drain the ice cap through breaks in the mountain chain, and from other points we can view bits and pieces of the ice fields, but the ice cap itself exists almost in myth, in a world beyond men. No man makes his home there, and only the most intrepid access this frozen fastness—and even they cannot stay for long.

Driven ashore by the remorseless west wind, storms blast out of the southern ocean, seethe over the ice cap, and guard the summits of the Patagonian Andes with Olympian fury. The leading edge of a storm often reveals Fitzroy as a threatening shadow within the churning clouds, but of Cerro Torre there is seldom any trace. Typically, the storm expends its moisture on the ice cap and mountains, but the power of the wind remains as it bursts free of the peaks and surges across the steppes east of the Andes. Above the desert steppes the west wind strings the clouds out into stacks and lines of saucer- and cigar-shaped lenticular clouds, clouds that run downwind and fade into the blue sky until all that remains of the storms is the wind, the gusting wind, the ceaseless, ceaseless wind.

When rare clear skies greet the rising sun, Fitzroy, Cerro Torre, and their satellites are bathed with purple, blue, rose, and gold light. In such outlandish beauty, the ice and stone heights seem to hold forth the ultimate promise. But late in the day, when the sun sinks to the west, those same mountain faces are shadowed and ominous, ironbound like the walls of Dante’s City of Dis. Then, as the sun drops unseen into the ice cap beyond the mountains, hellfire burns atop the mountain rampart.

Stories of fear, suffering, and failure stop most climbers from coming to Patagonia, and the stories accurately reflect reality. The mountains have no generosity and no justice. They stand unmoved by the human dramas that play out on their flanks, and they give and take with unknowable whim. We have only the dignity of persistence with which to combat this terrible faceless indifference.

The Patagonian gauntlet of hardship cannot be evaded. Frustration builds for climbers as attempt after arduous attempt is rejected by southern storms. Few have the mental fortitude to withstand the repeated failures coupled with the extended inactivity the bad weather enforces. But there are a handful of climbers who find the opposing miseries of the Patagonian Andes irresistible and are repeatedly drawn to this proving ground.

For many years I have been just such a human comet, in long orbits around the obelisks of Patagonia. Seven times I’ve made the pilgrimage. And I will go back, for the times that I spend in those mountains are the most charged moments of my life. In the mountains, life sings. Normal life can be such drudgery; little seems important. But in the mountains, all is different, for the alpine life is a life of consequence. In Patagonia every act, every choice, is significant. The myriad moods of the world matter. Has the wind shifted? Did the clouds rise or lower? Has it snowed much recently? Did it freeze last night? Climbers in the Patagonian Andes are as subject to the tyrannies of wind and storm as were the sailors in the age of tall wooden ships. The pulse of the world ran through their veins, and, in the mountains, it runs through mine.

•

I first arrived in Patagonia, the better part of a decade ago, with a torn backpack, battered tennis shoes, a few hundred dollars in my pocket, my ragged passport, and two letters from my girlfriend about the shaky ground we stood on. Nagging somewhere behind were the never-ending expectations of my driven, success-oriented mother and father for their West Point graduate but otherwise disappointing son. I had followed a dream to the peaks of Patagonia, but, nearing thirty, I was too old for purposeless endeavor, too uninterested in the cubicle world of the corporate workplace to build a career, and far too much in love with mountains to abandon them.

Now, my Patagonian adventures shimmer in my memory with the hammered silver look of the sun on wind-ruffled water. I could sort them into chronological order, but that’s not how I live them. To me, these memories are a tapestry without end or beginning. On these mountain expeditions I have discovered my compass, and it is the harsh discipline of the alpine way. The same final destination awaits us all, climbers and flatlanders alike. In the meantime, there is only the path. For me, it is enough.

My Patagonia is never far buried. Whenever I pull Patagonia into the forefront of my mind, which I do many times a day, I see a vision of the great peaks as they soar up into a sky full of angry clouds. I hear the terrible wind. And I feel fear.

But why climb? And why climb in Patagonia, where storm and mountain are so cruel? I am regularly asked why and I hate the question because the answer refuses distillation, and my inability to produce an adequate quip makes me seem an inarticulate fool. There is no sentence, no paragraph that captures the answer. Virtually everything that I know I have learned in the mountains, for only in such an elemental realm is truth undiluted. Mountains, and mostly the mountains of Patagonia, have taught me what I know about terror and joy; friendship; mirth and gravity; courage and cowardice and when to take a risk; success and failure; persistence, patience, endurance, and opportunity. To them I owe my most extreme visions of beauty and most of what I know about myself. But climbing is so much more than a series of schoolmaster’s lessons, and I resort to writing in the hope that when our shared journey is over you will feel the answer to the question why in your heart and guts as I feel it in mine. And if I fail at that task—as I almost certainly will—then I hope that you will at least enjoy these stories from my alpine life.

•

In Patagonia a storm clears and the alpine monoliths stand like teeth set in a dragon’s jaw. The last shreds of cloud fade into the firmament. The message broadcast from the peaks is as jarring as the scream of a train whistle. “Show yourself,” they say. Few moments bristle with as much opportunity. And before such uncaring majesty I wrestle my twin demons of fear and desire. Do I want this? Who am I? Is it enough? I wonder every time. Those who don’t seek out such moments of beauty, passion, and intensity don’t know themselves as well as they should. People may say that alpinism is a fool’s game full of meaningless risk, and they may be right, but I climb because I thirst to throw back the margins of my world. There remains so much that I do not know.

From the Hardcover edition.

An otherworldly range of mountains exists in Patagonia, at the southern end of the Americas. It is a sublime range, where ice and granite soar with a dancer’s grace. From the mountains’ feet tumble glaciers and dark forests of beech. The summits float in the southern sky, impossibly remote. Climbers who gaze upon these wonders ache to unlock their secrets. Hard, steep, massive, these might be our planet’s most perfect mountains. To court these summits is to graft fear to your heart, for all is not idyllic beauty among the great peaks of Patagonia. They stand squarely athwart what sailors refer to as the “roaring forties” and “furious fifties”—that region of the Southern Hemisphere between 40° and 60° south latitude known for ferocious wind and storm. The violent weather spawned over the great south sea charges through the Patagonian Andes with gale-force wind, roaring cloud, and stinging snow. Buried like a rapier deep into the heart of the southern ocean, Patagonia is a land trapped between angry torrents of sea and sky.

The horrendous weather more than makes up for the fact that the mountains of Patagonia do not count extreme altitude as a weapon. Altitude is only one aspect of climbing difficulty. The enormous walls of Patagonia demand fast, efficient, and expert practice of every climbing technique. Wealthy dilettantes cannot buy their way onto these exclusive summits. Only years of dedication to the alpine trade earn a climber the right to gain a Patagonian summit.

Cerro Fitzroy and Cerro Torre are the two crown jewels of the range. Seen from across the wind-swept scrub of the steppes to the east, they are the two crux battlements in the long Andean rampart. Far outdoing the Great Pyramids, Fitzroy’s stone bulk towers 10,000 feet over the arid plains and dominates the landscape like a barbarian king. Beside and a bit behind the king rises Cerro Torre, his royal consort, a graceful obelisk: tall, slender, vertiginous, elusive, hers the very form of alpine perfection. Although Fitzroy is a few hundred feet taller, Cerro Torre exceeds the king in every aspect except size—in difficulty, in threat, in promise, in beauty, in subtlety, and in the savageness of her fury. Cerro Fitzroy and Cerro Torre shoulder the sky like titans.

Cerro Torre stands at the left end of a line of towers, all divided from Fitzroy and his satellites by a deep valley and a flowing glacier. Fitzroy’s half-dozen satellites form a horseshoe to the left and right of the king. Anywhere else, the peaks that flank Fitzroy and Cerro Torre would be centerpiece summits; here in Patagonia they are the palace guard.

Beyond the mountains to the west lies the Southern Patagonian Ice Cap. The ice cap runs north-south like a long irregular cigar, bounded on one side by the front range of the Andes, and on the other by the Pacific Ocean. At its widest point, twenty-five miles north of the Fitzroy massif, the ice cap is almost sixty miles across. At its narrowest, sixty miles south of Fitzroy, less than ten miles of ice separate the Pacific Ocean in Fiordo Peel from fresh waters that flow into the Brazo Mayor (the major arm) of Lago Argentino. From north to south the ice cap is 225 miles long, and without counting the many glaciers that drain it, the surface of the ice cap measures more than 5,000 square miles. It is our world’s largest nonpolar expanse of ice and one of the least knowable landscapes on earth. From no point in the settled world can one get a true impression of the ice cap, for the Andes block the view of it from the inhabited desert to the east. There are places from which we can observe the glaciers that drain the ice cap through breaks in the mountain chain, and from other points we can view bits and pieces of the ice fields, but the ice cap itself exists almost in myth, in a world beyond men. No man makes his home there, and only the most intrepid access this frozen fastness—and even they cannot stay for long.

Driven ashore by the remorseless west wind, storms blast out of the southern ocean, seethe over the ice cap, and guard the summits of the Patagonian Andes with Olympian fury. The leading edge of a storm often reveals Fitzroy as a threatening shadow within the churning clouds, but of Cerro Torre there is seldom any trace. Typically, the storm expends its moisture on the ice cap and mountains, but the power of the wind remains as it bursts free of the peaks and surges across the steppes east of the Andes. Above the desert steppes the west wind strings the clouds out into stacks and lines of saucer- and cigar-shaped lenticular clouds, clouds that run downwind and fade into the blue sky until all that remains of the storms is the wind, the gusting wind, the ceaseless, ceaseless wind.

When rare clear skies greet the rising sun, Fitzroy, Cerro Torre, and their satellites are bathed with purple, blue, rose, and gold light. In such outlandish beauty, the ice and stone heights seem to hold forth the ultimate promise. But late in the day, when the sun sinks to the west, those same mountain faces are shadowed and ominous, ironbound like the walls of Dante’s City of Dis. Then, as the sun drops unseen into the ice cap beyond the mountains, hellfire burns atop the mountain rampart.

Stories of fear, suffering, and failure stop most climbers from coming to Patagonia, and the stories accurately reflect reality. The mountains have no generosity and no justice. They stand unmoved by the human dramas that play out on their flanks, and they give and take with unknowable whim. We have only the dignity of persistence with which to combat this terrible faceless indifference.

The Patagonian gauntlet of hardship cannot be evaded. Frustration builds for climbers as attempt after arduous attempt is rejected by southern storms. Few have the mental fortitude to withstand the repeated failures coupled with the extended inactivity the bad weather enforces. But there are a handful of climbers who find the opposing miseries of the Patagonian Andes irresistible and are repeatedly drawn to this proving ground.

For many years I have been just such a human comet, in long orbits around the obelisks of Patagonia. Seven times I’ve made the pilgrimage. And I will go back, for the times that I spend in those mountains are the most charged moments of my life. In the mountains, life sings. Normal life can be such drudgery; little seems important. But in the mountains, all is different, for the alpine life is a life of consequence. In Patagonia every act, every choice, is significant. The myriad moods of the world matter. Has the wind shifted? Did the clouds rise or lower? Has it snowed much recently? Did it freeze last night? Climbers in the Patagonian Andes are as subject to the tyrannies of wind and storm as were the sailors in the age of tall wooden ships. The pulse of the world ran through their veins, and, in the mountains, it runs through mine.

•

I first arrived in Patagonia, the better part of a decade ago, with a torn backpack, battered tennis shoes, a few hundred dollars in my pocket, my ragged passport, and two letters from my girlfriend about the shaky ground we stood on. Nagging somewhere behind were the never-ending expectations of my driven, success-oriented mother and father for their West Point graduate but otherwise disappointing son. I had followed a dream to the peaks of Patagonia, but, nearing thirty, I was too old for purposeless endeavor, too uninterested in the cubicle world of the corporate workplace to build a career, and far too much in love with mountains to abandon them.

Now, my Patagonian adventures shimmer in my memory with the hammered silver look of the sun on wind-ruffled water. I could sort them into chronological order, but that’s not how I live them. To me, these memories are a tapestry without end or beginning. On these mountain expeditions I have discovered my compass, and it is the harsh discipline of the alpine way. The same final destination awaits us all, climbers and flatlanders alike. In the meantime, there is only the path. For me, it is enough.

My Patagonia is never far buried. Whenever I pull Patagonia into the forefront of my mind, which I do many times a day, I see a vision of the great peaks as they soar up into a sky full of angry clouds. I hear the terrible wind. And I feel fear.

But why climb? And why climb in Patagonia, where storm and mountain are so cruel? I am regularly asked why and I hate the question because the answer refuses distillation, and my inability to produce an adequate quip makes me seem an inarticulate fool. There is no sentence, no paragraph that captures the answer. Virtually everything that I know I have learned in the mountains, for only in such an elemental realm is truth undiluted. Mountains, and mostly the mountains of Patagonia, have taught me what I know about terror and joy; friendship; mirth and gravity; courage and cowardice and when to take a risk; success and failure; persistence, patience, endurance, and opportunity. To them I owe my most extreme visions of beauty and most of what I know about myself. But climbing is so much more than a series of schoolmaster’s lessons, and I resort to writing in the hope that when our shared journey is over you will feel the answer to the question why in your heart and guts as I feel it in mine. And if I fail at that task—as I almost certainly will—then I hope that you will at least enjoy these stories from my alpine life.

•

In Patagonia a storm clears and the alpine monoliths stand like teeth set in a dragon’s jaw. The last shreds of cloud fade into the firmament. The message broadcast from the peaks is as jarring as the scream of a train whistle. “Show yourself,” they say. Few moments bristle with as much opportunity. And before such uncaring majesty I wrestle my twin demons of fear and desire. Do I want this? Who am I? Is it enough? I wonder every time. Those who don’t seek out such moments of beauty, passion, and intensity don’t know themselves as well as they should. People may say that alpinism is a fool’s game full of meaningless risk, and they may be right, but I climb because I thirst to throw back the margins of my world. There remains so much that I do not know.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

Enduring Patagonia, " with its exhilarating yet poetic voice and extraordinary color photos, chronicles one man's obsession with the wind-swept mountains and steppes of this strange part of the world made famous by Magellan and Darwin.