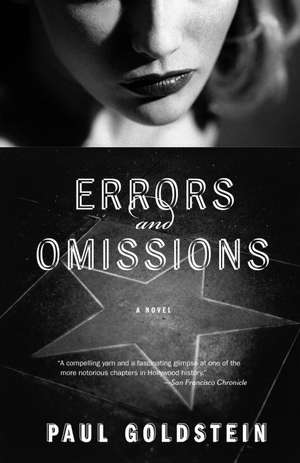

Errors and Omissions: Michael Seeley Mystery

Autor Paul Goldsteinen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2007

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Listen Up (2006)

Preț: 80.16 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 120

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.34€ • 16.05$ • 12.74£

15.34€ • 16.05$ • 12.74£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307274892

ISBN-10: 0307274896

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 148 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Seria Michael Seeley Mystery

ISBN-10: 0307274896

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 148 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Anchor Books

Seria Michael Seeley Mystery

Notă biografică

Paul Goldstein is the Lillick Professor of Law at Stanford Law School and is widely recognized as one of the country's leading authorities on intellectual property law. A graduate of Brandeis University and Columbia Law School, he is Of Counsel to the law firm of Morrison & Foerster LLP and has regularly been included in Best Lawyers in America. He has testified before congressional committees dealing with intellectual property issues and has been an invited expert at international government meetings on copyright issues. A native of New York, he now lives in Menlo Park, California, with his wife and daughter.

Extras

ONE

The worst part of being drunk before breakfast is the hangover that returns before noon.

Michael Seeley's head throbbed. He was tall and ruddy, with an athlete's vigor, but he felt compressed by the narrow room. Like the courtroom next door, the anteroom to Judge Randall Rappaport's chambers was designed for intimidation, not comfort: high ceiling, dark wood, brass fittings, wood chairs with no padding. There were no magazines or newspapers for distraction, not even a legal newspaper or law journal. A leather-bound volume the size of a Bible was carefully centered on a mahogany side table: The Collected Opinions (1985-2005) of the Honorable Randall Rappaport, Justice of the Supreme Court of New York.

The other person in the room, Noel Emmert, hadn't acknowledged Seeley when he came in, and it wasn't until after Seeley inspected the book and returned it to the table that Emmert spoke.

"How's the intellectual property business, counselor?" There was an edge to Emmert's voice, as if he were delivering the punch line to a story.

Emmert's law practice was in county and state courts like this one, in a gray warren of pillared buildings off Foley Square at the bottom of Manhattan. Seeley practiced mainly in the federal courts on Pearl Street, around the corner.

Seeley said, "How's the real property business?"

Emmert gestured, so-so. "Is this going to be a long waltz, counselor, or are we ready to settle?"

Seeley said, "Precisely."

Emmert's eyebrows arched and he shot Seeley a look. "You know," he said, "the law is truly humbling, if you think about it. Your guy sells a piece of crap sculpture to my guy, my guy decides to fix it up with a coat of paint, and before you know it, we have a lawsuit. Two professionals, me and you, spending our time and our clients' money fighting over an issue that's worth--what?--peanuts."

Seeley said, "It's funny, the way you do that."

"What's that?"

"The way you don't say, 'law.' You say 'the law.' There's a nobility to it."

"I never thought about it. Maybe I picked it up in law school."

"That's what I was thinking."

Given a choice, Seeley preferred the public theater of the courtroom where the playing field is level and a lawyer who does his homework has a better than average chance of winning. In judge's chambers, where decisions are private and unreviewable, the averages were out of his control.

The previous night, fueled by gin, Seeley had plotted his strategy for the morning meeting until he passed out on the bed in his room at the University Club. He came to five hours later, murderously hungover. He fumbled a small handful of ice cubes from the insulated bucket on the nightstand, pressed them against his forehead, then dropped them into an empty tumbler. Staggering to the dingy bathroom, Seeley's single thought was to dissolve the thick layers of gauze that encased his brain. He uncapped the fresh bottle of Bombay gin he had hidden beneath the sink and filled the tumbler to within a quarter-inch of the rim. He sipped tentatively at the bright, metallic liquid, took his time to study the University Club crest etched neatly into the glass, then, shuddering, gagging once, took the rest of the contents down in a succession of short, greedy gulps. He reached through the plastic curtain behind him and turned on the shower full force. Filling the tumbler a second time, he nursed the drink while he waited for the steam to rise. When he climbed through the curtain into the punishing needles, his mind was already clearing.

Now, in Rappaport's anteroom, the two tumblers of gin were dying inside him, and a burrowing thirst had taken over. He needed a drink. His hands clenched his knees. When he looked down he saw that the suit pants and jacket didn't match--both were dark gray, but one was glen plaid, the other herringbone. Although the light in the room at the University Club was poor, this hadn't happened before. Rappaport's secretary came in and announced that the judge was ready to see them.

Busy signing papers, Rappaport took a full minute before indicating the two empty chairs that faced him, still not looking up from his desk. It was September and the weather was warm, but the judge had on a three-piece suit with a gold chain looped through the vest and black judicial robes open over that. A few strands of gray hair had been carefully combed and plastered across a white scalp. He could have been a child in the tall chair. Seeley would bet that when Rappaport told people he was a supreme court justice he didn't bother to add that there were almost four hundred other supreme court justices in the state. Because of a historical quirk in the way courts were designated in New York State's judicial hierarchy, the supreme court was in fact among the lowest courts in the judicial system, not the highest.

Rappaport read from the paper in front of him. "Minietello v. Weber Properties." When he finally looked up, his expression was a scowl. "Where are your clients, counselors? Where's Mr. Minietello? Where's Mr. Weber?" The voice was nasal, aggrieved. "Surely, when he scheduled this meeting, my clerk reminded you of the standing order. Your clients must be present any time there is a settlement conference before a justice of the supreme court. Mr. Emmert, you have practiced here long enough to know that."

"It's a new requirement, Your Honor--"

"But a mandatory one."

"I have consulted with my client on the point, Your Honor, and he has agreed to waive a personal appearance."

"This is not a requirement that can be waived, counselor." The two could have been volleying at tennis. "I want your clients here. I see too many lawyers rejecting settlements that, if the client knew the details, the client would gladly accept. And you, Mr. . . ." Rappaport's tiny fingers, a busy rodent's, sorted through a pile of papers, searching for an appearance sheet or an appointment diary. This was playacting, Seeley knew, the way a small man bullies a newcomer to his domain. The judge knew his name; it was on the same sheet as the names of the parties. Finally, Rappaport found the paper he pretended to be looking for. "Mr. Seeley. What about your client? Is he waiving, too?"

"He was detained, Your Honor, but he's on his way."

Seeley had made a detour from his room at the University Club to his office on Sixth Avenue in midtown to collect a briefcase, and there had fallen into a long conversation with one of the mailboys about the Mets losing a double-header the day before. Leaving the building in a hired car, he forgot his promise to pick up Gary Minietello at the sculptor's loft so they could review strategy for the settlement conference. Only when he was walking up the granite courthouse steps, already late for the meeting with Rappaport, did Seeley remember the promise. He made a rushed call for Minietello to meet him in chambers.

"So, we shall sit here and wait for Mr. Seeley's client."

Seeley had dealt with difficult judges before, but he had the feeling that Rappaport was going to be a special challenge.

The judge swiveled in his chair to Emmert. "You're Fordham, aren't you?"

"Two years behind Your Honor. Your name still echoed in the hallways. All the time I was there, the professors were still talking about when you destroyed the Columbia team in the moot court competition."

Rappaport beamed. "Harvard, too. In the finals. The Jesuits field a fine moot court team. Where did you attend school, Mr. Seeley?"

"Canisius."

"The Jesuit school upstate?"

Seeley nodded.

"I didn't know they had a law school."

"They don't. I went to college there."

"I was asking where you went to law school," Rappaport said.

Seeley knew that's what he had meant. "Harvard."

"I thought so. An Ivy Leaguer." The judge paused to think if he could make something more of that, and instead made a show of studying his wristwatch and adjusting the cuff of his shirt. "I have a heavy schedule today, counselors, and unlike you, I'm not paid by the hour. So why don't we get started. You can fill your client in when he arrives, Mr. Seeley. Mr. Emmert, I want you to brief your client, too." Again he searched through the papers on his desk. "Let me see if I can help you frame the issue here."

Every first-year law student knows that how a legal issue is posed inevitably determines how it is decided. Seeley said, "If Your Honor would allow me to state the issue--"

Rappaport waved him off. He had found the briefing memo. "Correct me if I am in error, counselors, but, as I understand it, what this little tempest is about is that your client, Mr. Seeley, sold one of his sculptures to Mr. Emmert's client, and now he wants to stop him from putting a coat of paint on it."

Minietello's sculpture consisted of a dozen or so rusted structural girders exploding through a brick wall in the lobby of a Park Avenue office building, the girders' extremities twisted and shredded as if from a violent explosion. The building, owned by Emmert's client, had been on the market for more than a year. A buyer had at last made an offer on the property, but insisted that the sculpture be cleaned up and painted. Minietello objected. None of his works had ever been painted; to do so, he told anyone who would listen, would violate the integrity of his vision. Seeley didn't care much for the sculpture, or for Minietello, but nonetheless won a temporary restraining order enjoining any alteration of the work. His next step, unless the Honorable Randall Rappaport forced a settlement on him, would be to go to trial and win a judgment making the injunction permanent.

Seeley had been waiting years for a case like this--the opportunity to establish a foothold in New York law for the principle that artists have moral as well as economic rights; that no one, not even the owner of a work of art, can alter the work without the artist's consent. "If Your Honor will--"

"So we have a straightforward clash of interests here," Rappaport said. His chair squeaked as it rocked in a steady rhythm. "Your client's aesthetic wishes on the one side, Mr. Seeley, and on the other side, the interest of Mr. Emmert's client in selling his property. What's not clear to me, Mr. Seeley, is how your client has been injured."

The judge might be a sanctimonious jerk, Seeley thought, but he was no fool. He had stripped the case to its core, leaving no rough edge on which Seeley could build an argument. Seeley could argue that Minietello's interests were not only aesthetic but that his reputation, and consequently his future income, would suffer as soon as word got out that one of his works had been altered. But that wasn't the principle for which he had filed the case.

Emmert nodded at Rappaport's words but didn't speak. When a judge is making your case for you, you don't interrupt.

"I would be interested in hearing what precedents you think you may have on your side." Rappaport was still looking at Seeley.

If the judge had read his brief, he knew there were no direct precedents to support his position. But neither had there been direct precedent for any of the great decisions that had challenged, and ultimately reversed, the authority of existing law. For Seeley, that was the great beauty of American law: if you were persistent, prepared thoroughly, and had justice on your side, you could change the law. "Your Honor, federal law already--"

"This is not federal court, counselor. This is New York Supreme Court."

Seeley's thick hair felt matted as he tried to massage away the throbbing at the back of his head. He was parched; just speaking felt like fingernails clawing at his throat. The meeting was not going as he had planned it the night before. His thoughts ricocheted from the judge to Noel Emmert--the lawyer had the flushed look of a man who liked a drink--to the bottles he had stashed in the credenza in his office uptown. What if the chrome carafe on Rappaport's side table were filled with iced gin? How else would a judge get through the tedium of the day?

"Every civilized country in the world," Seeley heard himself saying, "England, France, Germany--every one of these countries recognizes an artist's moral right. No court in any of these countries would hesitate to enjoin Mr. Emmert's client from disfiguring a work of art."

"Even assuming that to be the case," Rappaport said, still rocking, "this is not a federal court and this is not a French court, either." He tilted back in the chair and clasped his hands over his vest.

Seeley's thoughts turned to the number of ways he might strangle Rappaport. "It's a fundamental principle of decency that you can't take away an artist's right to the integrity of his work."

Emmert said, "What about my client? Maybe he's an artist, too. Maybe he thinks this piece of junk looks better painted."

"That's a foolish argument, and you know it." Seeley hadn't intended it, but his voice had risen. "Painting someone else's sculpture isn't art."

Rappaport smiled. "You must forgive Mr. Emmert. He lacks the advantage of a Harvard education."

Seeley tried to think of a smart remark that might turn this bond between Rappaport and Emmert in his favor, but realized he was lost. Still, the words flew out. "This case isn't just about sculptors. It will set a precedent for painters. Writers. Musicians." Why was he having such difficulty controlling his voice? This was closing argument, a high schooler's imitation of Clarence Darrow. "It makes no difference if the work is Picasso's Guernica or the image some prehistoric man painted on the wall of his cave." His voice rose perilously. "A work of art--any work of art--touches something sacred in us. To violate it--" Words that had seemed so eloquent the previous night now tasted like paper in Seeley's mouth; he gagged on them and hated himself for believing them.

"I don't know what they put up with in federal court, but I will not have voices raised in my chambers. Do you understand that, counselor?" Rappaport's voice was level, his chair still. He waited for Seeley's acknowledgment before continuing. He leaned over the desk, his hands spread before him. "Look, let's be practical about this. If ever there was a case that should settle, it is this one. On your client's side, Mr. Seeley, there are some injured sensitivities. That is understandable. As you have already acknowledged, there is no precedent, but I'll grant that juries can be unpredictable. Also, the appellate process may fail to correct an error by the jury. So I expect"--he turned to include Emmert--"Mr. Emmert might be prepared to offer a reasonable figure for settlement. Reasonable, but not exorbitant. After all, Mr. Emmert's client presumably paid the artist good value when he purchased the sculpture."

From the Hardcover edition.

The worst part of being drunk before breakfast is the hangover that returns before noon.

Michael Seeley's head throbbed. He was tall and ruddy, with an athlete's vigor, but he felt compressed by the narrow room. Like the courtroom next door, the anteroom to Judge Randall Rappaport's chambers was designed for intimidation, not comfort: high ceiling, dark wood, brass fittings, wood chairs with no padding. There were no magazines or newspapers for distraction, not even a legal newspaper or law journal. A leather-bound volume the size of a Bible was carefully centered on a mahogany side table: The Collected Opinions (1985-2005) of the Honorable Randall Rappaport, Justice of the Supreme Court of New York.

The other person in the room, Noel Emmert, hadn't acknowledged Seeley when he came in, and it wasn't until after Seeley inspected the book and returned it to the table that Emmert spoke.

"How's the intellectual property business, counselor?" There was an edge to Emmert's voice, as if he were delivering the punch line to a story.

Emmert's law practice was in county and state courts like this one, in a gray warren of pillared buildings off Foley Square at the bottom of Manhattan. Seeley practiced mainly in the federal courts on Pearl Street, around the corner.

Seeley said, "How's the real property business?"

Emmert gestured, so-so. "Is this going to be a long waltz, counselor, or are we ready to settle?"

Seeley said, "Precisely."

Emmert's eyebrows arched and he shot Seeley a look. "You know," he said, "the law is truly humbling, if you think about it. Your guy sells a piece of crap sculpture to my guy, my guy decides to fix it up with a coat of paint, and before you know it, we have a lawsuit. Two professionals, me and you, spending our time and our clients' money fighting over an issue that's worth--what?--peanuts."

Seeley said, "It's funny, the way you do that."

"What's that?"

"The way you don't say, 'law.' You say 'the law.' There's a nobility to it."

"I never thought about it. Maybe I picked it up in law school."

"That's what I was thinking."

Given a choice, Seeley preferred the public theater of the courtroom where the playing field is level and a lawyer who does his homework has a better than average chance of winning. In judge's chambers, where decisions are private and unreviewable, the averages were out of his control.

The previous night, fueled by gin, Seeley had plotted his strategy for the morning meeting until he passed out on the bed in his room at the University Club. He came to five hours later, murderously hungover. He fumbled a small handful of ice cubes from the insulated bucket on the nightstand, pressed them against his forehead, then dropped them into an empty tumbler. Staggering to the dingy bathroom, Seeley's single thought was to dissolve the thick layers of gauze that encased his brain. He uncapped the fresh bottle of Bombay gin he had hidden beneath the sink and filled the tumbler to within a quarter-inch of the rim. He sipped tentatively at the bright, metallic liquid, took his time to study the University Club crest etched neatly into the glass, then, shuddering, gagging once, took the rest of the contents down in a succession of short, greedy gulps. He reached through the plastic curtain behind him and turned on the shower full force. Filling the tumbler a second time, he nursed the drink while he waited for the steam to rise. When he climbed through the curtain into the punishing needles, his mind was already clearing.

Now, in Rappaport's anteroom, the two tumblers of gin were dying inside him, and a burrowing thirst had taken over. He needed a drink. His hands clenched his knees. When he looked down he saw that the suit pants and jacket didn't match--both were dark gray, but one was glen plaid, the other herringbone. Although the light in the room at the University Club was poor, this hadn't happened before. Rappaport's secretary came in and announced that the judge was ready to see them.

Busy signing papers, Rappaport took a full minute before indicating the two empty chairs that faced him, still not looking up from his desk. It was September and the weather was warm, but the judge had on a three-piece suit with a gold chain looped through the vest and black judicial robes open over that. A few strands of gray hair had been carefully combed and plastered across a white scalp. He could have been a child in the tall chair. Seeley would bet that when Rappaport told people he was a supreme court justice he didn't bother to add that there were almost four hundred other supreme court justices in the state. Because of a historical quirk in the way courts were designated in New York State's judicial hierarchy, the supreme court was in fact among the lowest courts in the judicial system, not the highest.

Rappaport read from the paper in front of him. "Minietello v. Weber Properties." When he finally looked up, his expression was a scowl. "Where are your clients, counselors? Where's Mr. Minietello? Where's Mr. Weber?" The voice was nasal, aggrieved. "Surely, when he scheduled this meeting, my clerk reminded you of the standing order. Your clients must be present any time there is a settlement conference before a justice of the supreme court. Mr. Emmert, you have practiced here long enough to know that."

"It's a new requirement, Your Honor--"

"But a mandatory one."

"I have consulted with my client on the point, Your Honor, and he has agreed to waive a personal appearance."

"This is not a requirement that can be waived, counselor." The two could have been volleying at tennis. "I want your clients here. I see too many lawyers rejecting settlements that, if the client knew the details, the client would gladly accept. And you, Mr. . . ." Rappaport's tiny fingers, a busy rodent's, sorted through a pile of papers, searching for an appearance sheet or an appointment diary. This was playacting, Seeley knew, the way a small man bullies a newcomer to his domain. The judge knew his name; it was on the same sheet as the names of the parties. Finally, Rappaport found the paper he pretended to be looking for. "Mr. Seeley. What about your client? Is he waiving, too?"

"He was detained, Your Honor, but he's on his way."

Seeley had made a detour from his room at the University Club to his office on Sixth Avenue in midtown to collect a briefcase, and there had fallen into a long conversation with one of the mailboys about the Mets losing a double-header the day before. Leaving the building in a hired car, he forgot his promise to pick up Gary Minietello at the sculptor's loft so they could review strategy for the settlement conference. Only when he was walking up the granite courthouse steps, already late for the meeting with Rappaport, did Seeley remember the promise. He made a rushed call for Minietello to meet him in chambers.

"So, we shall sit here and wait for Mr. Seeley's client."

Seeley had dealt with difficult judges before, but he had the feeling that Rappaport was going to be a special challenge.

The judge swiveled in his chair to Emmert. "You're Fordham, aren't you?"

"Two years behind Your Honor. Your name still echoed in the hallways. All the time I was there, the professors were still talking about when you destroyed the Columbia team in the moot court competition."

Rappaport beamed. "Harvard, too. In the finals. The Jesuits field a fine moot court team. Where did you attend school, Mr. Seeley?"

"Canisius."

"The Jesuit school upstate?"

Seeley nodded.

"I didn't know they had a law school."

"They don't. I went to college there."

"I was asking where you went to law school," Rappaport said.

Seeley knew that's what he had meant. "Harvard."

"I thought so. An Ivy Leaguer." The judge paused to think if he could make something more of that, and instead made a show of studying his wristwatch and adjusting the cuff of his shirt. "I have a heavy schedule today, counselors, and unlike you, I'm not paid by the hour. So why don't we get started. You can fill your client in when he arrives, Mr. Seeley. Mr. Emmert, I want you to brief your client, too." Again he searched through the papers on his desk. "Let me see if I can help you frame the issue here."

Every first-year law student knows that how a legal issue is posed inevitably determines how it is decided. Seeley said, "If Your Honor would allow me to state the issue--"

Rappaport waved him off. He had found the briefing memo. "Correct me if I am in error, counselors, but, as I understand it, what this little tempest is about is that your client, Mr. Seeley, sold one of his sculptures to Mr. Emmert's client, and now he wants to stop him from putting a coat of paint on it."

Minietello's sculpture consisted of a dozen or so rusted structural girders exploding through a brick wall in the lobby of a Park Avenue office building, the girders' extremities twisted and shredded as if from a violent explosion. The building, owned by Emmert's client, had been on the market for more than a year. A buyer had at last made an offer on the property, but insisted that the sculpture be cleaned up and painted. Minietello objected. None of his works had ever been painted; to do so, he told anyone who would listen, would violate the integrity of his vision. Seeley didn't care much for the sculpture, or for Minietello, but nonetheless won a temporary restraining order enjoining any alteration of the work. His next step, unless the Honorable Randall Rappaport forced a settlement on him, would be to go to trial and win a judgment making the injunction permanent.

Seeley had been waiting years for a case like this--the opportunity to establish a foothold in New York law for the principle that artists have moral as well as economic rights; that no one, not even the owner of a work of art, can alter the work without the artist's consent. "If Your Honor will--"

"So we have a straightforward clash of interests here," Rappaport said. His chair squeaked as it rocked in a steady rhythm. "Your client's aesthetic wishes on the one side, Mr. Seeley, and on the other side, the interest of Mr. Emmert's client in selling his property. What's not clear to me, Mr. Seeley, is how your client has been injured."

The judge might be a sanctimonious jerk, Seeley thought, but he was no fool. He had stripped the case to its core, leaving no rough edge on which Seeley could build an argument. Seeley could argue that Minietello's interests were not only aesthetic but that his reputation, and consequently his future income, would suffer as soon as word got out that one of his works had been altered. But that wasn't the principle for which he had filed the case.

Emmert nodded at Rappaport's words but didn't speak. When a judge is making your case for you, you don't interrupt.

"I would be interested in hearing what precedents you think you may have on your side." Rappaport was still looking at Seeley.

If the judge had read his brief, he knew there were no direct precedents to support his position. But neither had there been direct precedent for any of the great decisions that had challenged, and ultimately reversed, the authority of existing law. For Seeley, that was the great beauty of American law: if you were persistent, prepared thoroughly, and had justice on your side, you could change the law. "Your Honor, federal law already--"

"This is not federal court, counselor. This is New York Supreme Court."

Seeley's thick hair felt matted as he tried to massage away the throbbing at the back of his head. He was parched; just speaking felt like fingernails clawing at his throat. The meeting was not going as he had planned it the night before. His thoughts ricocheted from the judge to Noel Emmert--the lawyer had the flushed look of a man who liked a drink--to the bottles he had stashed in the credenza in his office uptown. What if the chrome carafe on Rappaport's side table were filled with iced gin? How else would a judge get through the tedium of the day?

"Every civilized country in the world," Seeley heard himself saying, "England, France, Germany--every one of these countries recognizes an artist's moral right. No court in any of these countries would hesitate to enjoin Mr. Emmert's client from disfiguring a work of art."

"Even assuming that to be the case," Rappaport said, still rocking, "this is not a federal court and this is not a French court, either." He tilted back in the chair and clasped his hands over his vest.

Seeley's thoughts turned to the number of ways he might strangle Rappaport. "It's a fundamental principle of decency that you can't take away an artist's right to the integrity of his work."

Emmert said, "What about my client? Maybe he's an artist, too. Maybe he thinks this piece of junk looks better painted."

"That's a foolish argument, and you know it." Seeley hadn't intended it, but his voice had risen. "Painting someone else's sculpture isn't art."

Rappaport smiled. "You must forgive Mr. Emmert. He lacks the advantage of a Harvard education."

Seeley tried to think of a smart remark that might turn this bond between Rappaport and Emmert in his favor, but realized he was lost. Still, the words flew out. "This case isn't just about sculptors. It will set a precedent for painters. Writers. Musicians." Why was he having such difficulty controlling his voice? This was closing argument, a high schooler's imitation of Clarence Darrow. "It makes no difference if the work is Picasso's Guernica or the image some prehistoric man painted on the wall of his cave." His voice rose perilously. "A work of art--any work of art--touches something sacred in us. To violate it--" Words that had seemed so eloquent the previous night now tasted like paper in Seeley's mouth; he gagged on them and hated himself for believing them.

"I don't know what they put up with in federal court, but I will not have voices raised in my chambers. Do you understand that, counselor?" Rappaport's voice was level, his chair still. He waited for Seeley's acknowledgment before continuing. He leaned over the desk, his hands spread before him. "Look, let's be practical about this. If ever there was a case that should settle, it is this one. On your client's side, Mr. Seeley, there are some injured sensitivities. That is understandable. As you have already acknowledged, there is no precedent, but I'll grant that juries can be unpredictable. Also, the appellate process may fail to correct an error by the jury. So I expect"--he turned to include Emmert--"Mr. Emmert might be prepared to offer a reasonable figure for settlement. Reasonable, but not exorbitant. After all, Mr. Emmert's client presumably paid the artist good value when he purchased the sculpture."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“A compelling yarn and a fascinating glimpse at one of the more notorious chapters in Hollywood history.”—The San Francisco Chronicle “It’s difficult to convey the mounting excitement with which I turned the pages. . . . the writing [is] masterful, not one wasted word. . . . A terrific read.” —Sue Grafton“Memorable [and] pleasurable. . . . Goldstein displays the keen eye and sure hand of a gifted writer.”—The Wall Street Journal“Compares favorably with the best legal thrillers of the likes of John Grisham. . . . [Errors and Omissions] qualifies Goldstein for a high position among recent crime fiction.”—Political Affairs

Descriere

From one of the foremost experts in the country on intellectual property law comes a gripping legal thriller of depth and complexity.

Premii

- Listen Up Editor's Choice, 2006