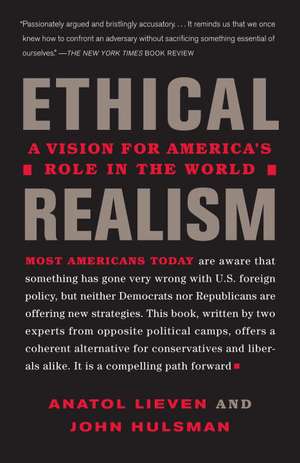

Ethical Realism: A Vision for America's Role in the World

Autor Anatol Lieven, John Hulsmanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2007

Preț: 77.08 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 116

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.75€ • 15.24$ • 12.28£

14.75€ • 15.24$ • 12.28£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307277381

ISBN-10: 0307277380

Pagini: 199

Dimensiuni: 134 x 201 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 0307277380

Pagini: 199

Dimensiuni: 134 x 201 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Anatol Lieven is a senior research fellow at the New America Foundation and is the author of America Right or Wrong: An Anatomy of American Nationalism. He writes regularly for the Financial Times and the International Herald Tribune, among other publications. He lives in Washington, D.C.

John Hulsman is a former senior research fellow at The Heritage Foundation and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, as well as a contributing editor to The National Interest. He advises congressional leaders from both parties on foreign policy issues and makes regular appearances on ABC, CBS, Fox News, CNN, MSNBC, PBS, and the BBC. He lives in Culpeper, Virginia.

From the Hardcover edition.

John Hulsman is a former senior research fellow at The Heritage Foundation and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, as well as a contributing editor to The National Interest. He advises congressional leaders from both parties on foreign policy issues and makes regular appearances on ABC, CBS, Fox News, CNN, MSNBC, PBS, and the BBC. He lives in Culpeper, Virginia.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

One

Lessons of the Truman-

Eisenhower Moment

The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.

–oliver wendell holmes

With the passing of George Kennan in March 2005, the last living member of the Truman administration, the most successful foreign policy team in modern American history, left the stage. Between 1945 and 1960, these men and their successors and de facto allies in the Eisenhower administration set the United States on the road to eventual victory in the Cold War. The success of the containment doctrine that they developed can be gauged by the fact that it was followed in one form or another until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The triumph of the Truman years is all the more remarkable given that at the time of his swearing in, Harry Truman’s only trip overseas had been as an artillery officer in World War I; he had never spoken to a Soviet citizen. What he did possess was native shrewdness; tremendous strength of character; deep patriotism and sense of responsibility; and not least, the self-confidence to appoint brilliant men to positions of responsibility and then back them to the hilt. For in the wake of World War II, with a new threat, Soviet Communism, facing the West, Truman and his team, somewhat unexpectedly followed by Eisenhower, established an entirely new model for American foreign policy that led to victory against an entirely different sort of enemy.

The threat of Soviet Communist expansionism after 1945 was not a sudden shock like Pearl Harbor or 9/11, but it was just as much of a jolt to the American system and attitudes. For the first time, the United States was faced with the need for permanent mobilization to meet a severe and open-ended global threat and maintain an indefinite and massive set of global commitments.

Until the Cold War, America’s military commitments beyond its shores had always been brief, and with a predictable end. Most were short wars, after which it was assumed that America would go home; in the case of the occupations of the Philippines and several Caribbean nations after the defeat of Spain, the overseas commitments were small-scale. None of them required the United States to create a permanent conscript army or permanent security institutions like those the European states had had to develop over the centuries. Indeed, much of America’s political tradition, since the first days of the colonies, was founded precisely on hostility to such “standing armies.”

Not only did the Cold War now require such massive permanent mobilization, but the existence of atomic bombs made a general war with a relatively quick victory with limited losses–as in previous wars–difficult to imagine. After the United States and the Soviet Union both developed thermonuclear weapons, easy victory was almost impossible to imagine. The United States had to learn to live for the first time with permanent tension, which some found unbearable.

The war on terror is of course very different, but it is equally difficult to imagine any quick and successful end to it, especially through U.S. military action. Terrorism, like nuclear weapons, makes nonsense of General Douglas A. MacArthur’s dictum that “in war there can be no substitute for victory.” The substitute is holding the line and preventing the enemy from winning–which is what civilized states have been doing vis-ˆ-vis barbarian enemies since the beginning of recorded time. The Byzantines never did “win” conclusively against their enemies, any more than successive Chinese dynasties did against their own barbarian menace. But they held them off for centuries, during which time great civilizations flourished and eventually produced the societies and technologies by which the barbarian threat could be extinguished.

The Soviet threat therefore required a radical reconfiguration of U.S. institutions and global strategy. Even more important, it required a fundamental rethinking of America’s vision of its role in the world–“a complete revolution in American foreign policy and the attitude of the American people,” as Truman’s secretary of state Dean Acheson called it.#1 The old comforting nostrums of George Washington’s Farewell Address, of avoiding foreign entanglements at all costs, made little sense in a world where ignoring Adolf Hitler’s rise had already led to such cataclysmic results. Ignoring Soviet ambitions to dominate the world was simply no longer an option. New thinking, based on these new realities, was vital.

The Truman administration, followed by that of Eisenhower, recognized the radically new, different, and long-term nature of the struggle, and developed radically new strategies, institutions, and forces to wage it. The National Security Act of 1947, introduced eighteen months after relations with the Soviet Union began their radical downhill slide, created a range of new and vitally important government institutions, including the National Security Council, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Air Force (previously a branch of the U.S. Army). It also created strict and clear rules for operating procedures and relations between them. The revelation of the catastrophic danger of terrorism that occurred on September 11, 2001, demanded an equally new institutional and strategic response from the Bush administration–but did not receive it.

The Truman-Eisenhower period is worth studying because it is an example of radical reform in the midst of crisis, but also because of who was proved to be right by history and who was proved to be wrong. Those who have obviously been proved right were the authors of a tough but restrained strategy of “containing” Soviet expansionism, without launching or unduly risking war; and of meanwhile undermining Communism through the force of the West’s democratic and free market example. This took longer than many of them had hoped–but given that we won completely in the end, a few decades of mostly peaceful struggle were surely preferable to nuclear cataclysm.

By contrast, the “preventive war” and “rollback” schools of thought during the Cold War were proved wrong on just about everything. And a river of wrongness has flowed down from them to their neoconservative descendants of today, many of whose ideas derive directly from those of the hard-liners of the Truman and Eisenhower eras. Would you buy advice on your investments from a firm that has been wrong for sixty years?

For despite hard-liners on the right and appeasers on the left who attempted to derail the Truman-Eisenhower moment, the establishment achieved a fundamental and brilliantly successful rethinking of strategy: the containment doctrine that defined the Truman-Eisenhower moment signaled something entirely new for the United States and the world. Such is also our task today. The efforts of the Bush administration and the neoconservatives to push their agenda have come to predictable grief in Iraq and elsewhere. We must invent something new if we are to avoid the fate of confusion, decline, and ultimate defeat that continuing to pursue such a course is fated to hold. Fortunately, America’s past, and especially the Truman-Eisenhower era, provide inspiration on how to proceed.

The Truman Record

The Truman administration is a tale of both what it did (the Marshall Plan and the creation of NATO) and what it did not do (turn the Korean War into a world war). Its guiding foreign policy strategy, the containment doctrine, was clearly laid down at the start, but also evolved over time, as events influenced the thinking of the administration.

Despite the evident hostility of Stalin’s regime toward the West, abandoning the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union was not easy for the Truman administration. Although the U.S. establish ment and most ordinary Americans had always been deeply suspicious of Communism, the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union had created real feelings of friendship, and even more important, passionate hopes that long-term U.S.-Soviet cooperation would ensure peace and progress for humanity in general.

Initially, therefore, it was not the Red Army’s conquest of Eastern Europe in the final days of World War II that primarily unnerved Washington. Rather, Moscow began to set its sights on areas of clear strategic importance to the United States that lay beyond the war’s demarcation lines; in seeking to maintain its military presence in northern Iran in 1946 and in threatening Turkey’s sole control of the Dardanelles strait, it appeared that Moscow was, like the Nazis, trying rapidly to dominate the world.

George Kennan, then acting head of the U.S. embassy in Moscow, proposed a different explanation of Soviet behavior. His “Long Telegram” back to Washington is probably the single most important State Department cable ever written. For what Kennan did was to give voice to the growing American unease about Soviet expansionism, give an explanation of what motivated this expansionism and how it operated, and propound a strategy for dealing with it. He laid the intellectual basis for the containment doctrine that was eventually to bring the United States victory in the Cold War.

In an essay of 1947 based on the telegram, Kennan wrote,

The first of the [Soviet Communist] concepts is that of the innate antagonism between capitalism and socialism. . . . It must invariably be assumed in Moscow that the aims of the capitalist worlds are antagonistic to the Soviet regime, and therefore to the interests of the peoples it controls. . . . And from [this belief in natural antagonism] flow many of the phenomena which we find disturbing in the Kremlin’s conduct of foreign policy: the secretiveness, the lack of frankness, the duplicity, the wary suspiciousness and the basic unfriendliness of purpose.2

Today, this portrayal seems self-evident, denied only by a few elements of the old left. It is difficult to exaggerate, however, its startling and essential effect on Americans of early 1946, and especially liberals, passionately anxious to believe that the Soviet Union, which had made such terrible sacrifices in the struggle against Nazism, and “good old Uncle Joe” Stalin himself, were basically decent, and wanted good relations with the United States.

Kennan saw Stalin and the Soviet Communists as essentially expansionist, but also cautious, because they saw history as on their side and therefore could afford to wait. Compared with the Nazis, they were more rational, and would not force the pace in their drive for global dominance. The Soviet leadership therefore proceeded not according to some strategic doctrine, but opportunistically. They would constantly probe for political, social, and economic weaknesses and divisions in the non-Communist world, seeking to exploit these to their benefit. Unlike the Nazis, however, they would also stop or retreat wherever they met strong resistance, rather than driving ahead, ignoring the risks and the cost. There was rarely a need for America to adopt “threats or blustering or superfluous gestures of outward ‘toughness.’ ” Instead, Kennan said,

It is a sine qua non of successful dealing with Russia that the government in question should remain at all times cool and collected and that its demands on Russian policy should be put forward in such a manner as to leave the way open for a compliance not too detrimental to Russian prestige.

Kennan recommended that Washington adopt two broad strategic countermeasures. First, the containment doctrine drew demarcation lines between the non-Communist and Communist worlds, with the American priority going to bolster allies nearest the lines, such as West Germany, Iran, Greece, Turkey, Japan, and later, South Korea. Second, it would be critically important to build up the free world economically and socially, as Communism thrived on economic suffering, social conflict, and political chaos.#3

The Korean War is the classic example of the military aspects of containment being put to the test, with the United States and its allies–after stumbling very badly twice in the first six months of the war–ultimately defeating North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung’s dreams of a unified Communist Korea. It was preceded by U.S. and British measures to strengthen militarily the anti-Communist side in Greece’s civil war. The Marshall Plan, Truman’s grand effort to stabilize Western Europe, is the great expression of the equally critical nonmilitary aspects of the doctrine.4 This simple, carefully limited strategy was crowned by the fact that the Soviet Union ultimately committed suicide, much as Kennan had predicted with almost uncanny accuracy forty-five years before:

[Unless its Communist economy radically changes] Russia will remain economically a vulnerable and in some sense an impotent nation. . . . Soviet power is only a crust concealing an amorphous mass of human beings among whom no independent organizational structure is tolerated. . . . If, consequently, anything were ever to occur to disrupt the unity and efficacy of the Party as a political instrument, Soviet Russia might be changed overnight from one of the strongest to one of the weakest and most pitiable of national societies.

Rarely in history has such analytical brilliance led to such wise policy recommendations being followed over such a long period of time. Critical to this success was not only the wisdom of the policy itself, but the creation of bipartisan domestic consensus that–in the face of heavy odds–ensured that Truman’s strategy was followed by Eisenhower’s Republican administration.

Harry Truman succeeded in politically isolating the left wing of the Democratic Party, which favored some sort of accommodation with the U.S.S.R. (epitomized by former vice president and 1948 presidential candidate Henry Wallace). The hard-line, preventive war wing of the Republican Party, symbolized by General Douglas MacArthur, was likewise marginalized.

Instead of either accommodation or war, political competition with the Soviets became the modus operandi in the immediate post-1945 era. This state of affairs was reinforced by the election of Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, a Republican who essentially continued his Democratic predecessor’s strategy. In seeing off these threats to a bipartisan foreign policy, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations laid the basis for eventual victory in the Cold War.

The “Truman-Eisenhower moment” was also a “Churchill-Bevin moment,” when tough-minded members of Britain’s Labour government–including moderate socialists–joined with the Conservative opposition to create a new alliance with the United States to resist Soviet expansionism.#5 This contributed in turn to the rallying of both Christian Democrat and Social Democrat leaders across Western Europe to the same cause. None of this could have been achieved if the United States during that period had pursued a strategy of reckless ideological unilateralism.

Such unilateralism has been characteristic of today’s neoconservatives, and the Bush administration, and has created immense problems for U.S. strategy. For unilateralism can so easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to an America that cannot find allies even if it later seeks them. As the history of America and Europe in the early years of the Cold War makes clear, courting allies does not show weakness–it is a requirement of strategic success in a world where the United States is preeminent but not all-powerful, and is facing powerful enemies and intractable challenges.

The Truman-Eisenhower continuity did not stem from personal affinity between the two men; Truman never forgave Eisenhower for not defending General Marshall from the vile and unfounded attacks of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Nor did Eisenhower ever ask his predecessor for advice the way Truman had consulted former president Herbert Hoover. Well into his retirement, Truman could hardly say anything about Eisenhower without resorting to profanity.#6

Lessons of the Truman-

Eisenhower Moment

The best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.

–oliver wendell holmes

With the passing of George Kennan in March 2005, the last living member of the Truman administration, the most successful foreign policy team in modern American history, left the stage. Between 1945 and 1960, these men and their successors and de facto allies in the Eisenhower administration set the United States on the road to eventual victory in the Cold War. The success of the containment doctrine that they developed can be gauged by the fact that it was followed in one form or another until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The triumph of the Truman years is all the more remarkable given that at the time of his swearing in, Harry Truman’s only trip overseas had been as an artillery officer in World War I; he had never spoken to a Soviet citizen. What he did possess was native shrewdness; tremendous strength of character; deep patriotism and sense of responsibility; and not least, the self-confidence to appoint brilliant men to positions of responsibility and then back them to the hilt. For in the wake of World War II, with a new threat, Soviet Communism, facing the West, Truman and his team, somewhat unexpectedly followed by Eisenhower, established an entirely new model for American foreign policy that led to victory against an entirely different sort of enemy.

The threat of Soviet Communist expansionism after 1945 was not a sudden shock like Pearl Harbor or 9/11, but it was just as much of a jolt to the American system and attitudes. For the first time, the United States was faced with the need for permanent mobilization to meet a severe and open-ended global threat and maintain an indefinite and massive set of global commitments.

Until the Cold War, America’s military commitments beyond its shores had always been brief, and with a predictable end. Most were short wars, after which it was assumed that America would go home; in the case of the occupations of the Philippines and several Caribbean nations after the defeat of Spain, the overseas commitments were small-scale. None of them required the United States to create a permanent conscript army or permanent security institutions like those the European states had had to develop over the centuries. Indeed, much of America’s political tradition, since the first days of the colonies, was founded precisely on hostility to such “standing armies.”

Not only did the Cold War now require such massive permanent mobilization, but the existence of atomic bombs made a general war with a relatively quick victory with limited losses–as in previous wars–difficult to imagine. After the United States and the Soviet Union both developed thermonuclear weapons, easy victory was almost impossible to imagine. The United States had to learn to live for the first time with permanent tension, which some found unbearable.

The war on terror is of course very different, but it is equally difficult to imagine any quick and successful end to it, especially through U.S. military action. Terrorism, like nuclear weapons, makes nonsense of General Douglas A. MacArthur’s dictum that “in war there can be no substitute for victory.” The substitute is holding the line and preventing the enemy from winning–which is what civilized states have been doing vis-ˆ-vis barbarian enemies since the beginning of recorded time. The Byzantines never did “win” conclusively against their enemies, any more than successive Chinese dynasties did against their own barbarian menace. But they held them off for centuries, during which time great civilizations flourished and eventually produced the societies and technologies by which the barbarian threat could be extinguished.

The Soviet threat therefore required a radical reconfiguration of U.S. institutions and global strategy. Even more important, it required a fundamental rethinking of America’s vision of its role in the world–“a complete revolution in American foreign policy and the attitude of the American people,” as Truman’s secretary of state Dean Acheson called it.#1 The old comforting nostrums of George Washington’s Farewell Address, of avoiding foreign entanglements at all costs, made little sense in a world where ignoring Adolf Hitler’s rise had already led to such cataclysmic results. Ignoring Soviet ambitions to dominate the world was simply no longer an option. New thinking, based on these new realities, was vital.

The Truman administration, followed by that of Eisenhower, recognized the radically new, different, and long-term nature of the struggle, and developed radically new strategies, institutions, and forces to wage it. The National Security Act of 1947, introduced eighteen months after relations with the Soviet Union began their radical downhill slide, created a range of new and vitally important government institutions, including the National Security Council, the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Air Force (previously a branch of the U.S. Army). It also created strict and clear rules for operating procedures and relations between them. The revelation of the catastrophic danger of terrorism that occurred on September 11, 2001, demanded an equally new institutional and strategic response from the Bush administration–but did not receive it.

The Truman-Eisenhower period is worth studying because it is an example of radical reform in the midst of crisis, but also because of who was proved to be right by history and who was proved to be wrong. Those who have obviously been proved right were the authors of a tough but restrained strategy of “containing” Soviet expansionism, without launching or unduly risking war; and of meanwhile undermining Communism through the force of the West’s democratic and free market example. This took longer than many of them had hoped–but given that we won completely in the end, a few decades of mostly peaceful struggle were surely preferable to nuclear cataclysm.

By contrast, the “preventive war” and “rollback” schools of thought during the Cold War were proved wrong on just about everything. And a river of wrongness has flowed down from them to their neoconservative descendants of today, many of whose ideas derive directly from those of the hard-liners of the Truman and Eisenhower eras. Would you buy advice on your investments from a firm that has been wrong for sixty years?

For despite hard-liners on the right and appeasers on the left who attempted to derail the Truman-Eisenhower moment, the establishment achieved a fundamental and brilliantly successful rethinking of strategy: the containment doctrine that defined the Truman-Eisenhower moment signaled something entirely new for the United States and the world. Such is also our task today. The efforts of the Bush administration and the neoconservatives to push their agenda have come to predictable grief in Iraq and elsewhere. We must invent something new if we are to avoid the fate of confusion, decline, and ultimate defeat that continuing to pursue such a course is fated to hold. Fortunately, America’s past, and especially the Truman-Eisenhower era, provide inspiration on how to proceed.

The Truman Record

The Truman administration is a tale of both what it did (the Marshall Plan and the creation of NATO) and what it did not do (turn the Korean War into a world war). Its guiding foreign policy strategy, the containment doctrine, was clearly laid down at the start, but also evolved over time, as events influenced the thinking of the administration.

Despite the evident hostility of Stalin’s regime toward the West, abandoning the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union was not easy for the Truman administration. Although the U.S. establish ment and most ordinary Americans had always been deeply suspicious of Communism, the wartime alliance with the Soviet Union had created real feelings of friendship, and even more important, passionate hopes that long-term U.S.-Soviet cooperation would ensure peace and progress for humanity in general.

Initially, therefore, it was not the Red Army’s conquest of Eastern Europe in the final days of World War II that primarily unnerved Washington. Rather, Moscow began to set its sights on areas of clear strategic importance to the United States that lay beyond the war’s demarcation lines; in seeking to maintain its military presence in northern Iran in 1946 and in threatening Turkey’s sole control of the Dardanelles strait, it appeared that Moscow was, like the Nazis, trying rapidly to dominate the world.

George Kennan, then acting head of the U.S. embassy in Moscow, proposed a different explanation of Soviet behavior. His “Long Telegram” back to Washington is probably the single most important State Department cable ever written. For what Kennan did was to give voice to the growing American unease about Soviet expansionism, give an explanation of what motivated this expansionism and how it operated, and propound a strategy for dealing with it. He laid the intellectual basis for the containment doctrine that was eventually to bring the United States victory in the Cold War.

In an essay of 1947 based on the telegram, Kennan wrote,

The first of the [Soviet Communist] concepts is that of the innate antagonism between capitalism and socialism. . . . It must invariably be assumed in Moscow that the aims of the capitalist worlds are antagonistic to the Soviet regime, and therefore to the interests of the peoples it controls. . . . And from [this belief in natural antagonism] flow many of the phenomena which we find disturbing in the Kremlin’s conduct of foreign policy: the secretiveness, the lack of frankness, the duplicity, the wary suspiciousness and the basic unfriendliness of purpose.2

Today, this portrayal seems self-evident, denied only by a few elements of the old left. It is difficult to exaggerate, however, its startling and essential effect on Americans of early 1946, and especially liberals, passionately anxious to believe that the Soviet Union, which had made such terrible sacrifices in the struggle against Nazism, and “good old Uncle Joe” Stalin himself, were basically decent, and wanted good relations with the United States.

Kennan saw Stalin and the Soviet Communists as essentially expansionist, but also cautious, because they saw history as on their side and therefore could afford to wait. Compared with the Nazis, they were more rational, and would not force the pace in their drive for global dominance. The Soviet leadership therefore proceeded not according to some strategic doctrine, but opportunistically. They would constantly probe for political, social, and economic weaknesses and divisions in the non-Communist world, seeking to exploit these to their benefit. Unlike the Nazis, however, they would also stop or retreat wherever they met strong resistance, rather than driving ahead, ignoring the risks and the cost. There was rarely a need for America to adopt “threats or blustering or superfluous gestures of outward ‘toughness.’ ” Instead, Kennan said,

It is a sine qua non of successful dealing with Russia that the government in question should remain at all times cool and collected and that its demands on Russian policy should be put forward in such a manner as to leave the way open for a compliance not too detrimental to Russian prestige.

Kennan recommended that Washington adopt two broad strategic countermeasures. First, the containment doctrine drew demarcation lines between the non-Communist and Communist worlds, with the American priority going to bolster allies nearest the lines, such as West Germany, Iran, Greece, Turkey, Japan, and later, South Korea. Second, it would be critically important to build up the free world economically and socially, as Communism thrived on economic suffering, social conflict, and political chaos.#3

The Korean War is the classic example of the military aspects of containment being put to the test, with the United States and its allies–after stumbling very badly twice in the first six months of the war–ultimately defeating North Korean dictator Kim Il Sung’s dreams of a unified Communist Korea. It was preceded by U.S. and British measures to strengthen militarily the anti-Communist side in Greece’s civil war. The Marshall Plan, Truman’s grand effort to stabilize Western Europe, is the great expression of the equally critical nonmilitary aspects of the doctrine.4 This simple, carefully limited strategy was crowned by the fact that the Soviet Union ultimately committed suicide, much as Kennan had predicted with almost uncanny accuracy forty-five years before:

[Unless its Communist economy radically changes] Russia will remain economically a vulnerable and in some sense an impotent nation. . . . Soviet power is only a crust concealing an amorphous mass of human beings among whom no independent organizational structure is tolerated. . . . If, consequently, anything were ever to occur to disrupt the unity and efficacy of the Party as a political instrument, Soviet Russia might be changed overnight from one of the strongest to one of the weakest and most pitiable of national societies.

Rarely in history has such analytical brilliance led to such wise policy recommendations being followed over such a long period of time. Critical to this success was not only the wisdom of the policy itself, but the creation of bipartisan domestic consensus that–in the face of heavy odds–ensured that Truman’s strategy was followed by Eisenhower’s Republican administration.

Harry Truman succeeded in politically isolating the left wing of the Democratic Party, which favored some sort of accommodation with the U.S.S.R. (epitomized by former vice president and 1948 presidential candidate Henry Wallace). The hard-line, preventive war wing of the Republican Party, symbolized by General Douglas MacArthur, was likewise marginalized.

Instead of either accommodation or war, political competition with the Soviets became the modus operandi in the immediate post-1945 era. This state of affairs was reinforced by the election of Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, a Republican who essentially continued his Democratic predecessor’s strategy. In seeing off these threats to a bipartisan foreign policy, the Truman and Eisenhower administrations laid the basis for eventual victory in the Cold War.

The “Truman-Eisenhower moment” was also a “Churchill-Bevin moment,” when tough-minded members of Britain’s Labour government–including moderate socialists–joined with the Conservative opposition to create a new alliance with the United States to resist Soviet expansionism.#5 This contributed in turn to the rallying of both Christian Democrat and Social Democrat leaders across Western Europe to the same cause. None of this could have been achieved if the United States during that period had pursued a strategy of reckless ideological unilateralism.

Such unilateralism has been characteristic of today’s neoconservatives, and the Bush administration, and has created immense problems for U.S. strategy. For unilateralism can so easily become a self-fulfilling prophecy, leading to an America that cannot find allies even if it later seeks them. As the history of America and Europe in the early years of the Cold War makes clear, courting allies does not show weakness–it is a requirement of strategic success in a world where the United States is preeminent but not all-powerful, and is facing powerful enemies and intractable challenges.

The Truman-Eisenhower continuity did not stem from personal affinity between the two men; Truman never forgave Eisenhower for not defending General Marshall from the vile and unfounded attacks of Senator Joseph McCarthy. Nor did Eisenhower ever ask his predecessor for advice the way Truman had consulted former president Herbert Hoover. Well into his retirement, Truman could hardly say anything about Eisenhower without resorting to profanity.#6

Recenzii

“Passionately argued and bristlingly accusatory. It reminds us that we once knew how to confront an adversary without sacrificing something essential of ourselves.”—The New York Times“Lieven and Hulsman are passionate in their sobriety and remarkably concrete about the steps to be taken.” —The Atlantic Monthly“Makes a powerful case that the United States needs a foreign policy based on hard facts and what we can achieve with our available resources, in order not to retreat from a U.S. world role, but, on the contrary, ‘to live up to its glorious national promise.’ ” —General Brent Scowcroft, former national security adviser“A profoundly necessary alternative to the arrogance of preemptive warfare. . . . Ethical Realism is characterized by prudence, humility, understanding, responsibility, and genuine patriotism, and is deeply rooted in the best of America’s history.” —Senator Gary Hart