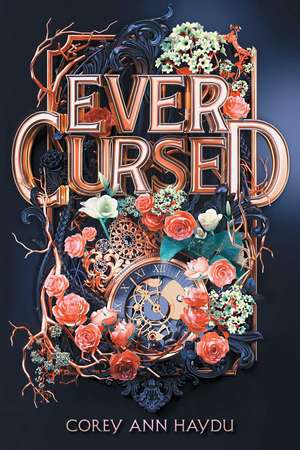

Ever Cursed

Autor Corey Ann Hayduen Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 noi 2021 – vârsta de la 14 ani

Damsel meets A Heart in a Body in the World in this incisive and lyrical feminist fairy tale about a princess determined to save her sisters from a curse, even if it means allying herself with the very witch who cast it.

The Princesses of Ever are beloved by the kingdom and their father, the King. They are cherished, admired.

Cursed.

Jane, Alice, Nora, Grace, and Eden carry the burden of being punished for a crime they did not commit, or even know about. They are each cursed to be Without one essential thing—the ability to eat, sleep, love, remember, or hope. And their mother, the Queen, is imprisoned, frozen in time in an unbreakable glass box.

But when Eden’s curse sets in on her thirteenth birthday, the princesses are given the opportunity to break the curse, preventing it from becoming a True Spell and dooming the princesses for life. To do this, they must confront the one who cast the spell—Reagan, a young witch who might not be the villain they thought—as well as the wickedness plaguing their own kingdom…and family.

Told through the eyes of Reagan and Jane—the witch and the bewitched—this insightful twist of a fairy tale explores power in a patriarchal kingdom not unlike our own.

Preț: 46.90 lei

Preț vechi: 57.76 lei

-19% Nou

Puncte Express: 70

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.97€ • 9.37$ • 7.43£

8.97€ • 9.37$ • 7.43£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-26 martie

Livrare express 28 februarie-06 martie pentru 31.22 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781534437043

ISBN-10: 1534437045

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: f-c scuff-proof matte lam cvr (no spfx)

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

ISBN-10: 1534437045

Pagini: 320

Ilustrații: f-c scuff-proof matte lam cvr (no spfx)

Dimensiuni: 140 x 210 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Colecția Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers

Notă biografică

Corey Ann Haydu is the author of OCD Love Story, Rules for Stealing Stars, Eventown, and several other critically acclaimed young adult and children’s novels. She currently teaches at the MFA Writing for Children program at Vermont College of Fine Arts and lives in Brooklyn, New York, with her husband and daughter. Learn more at CoreyAnnHaydu.com.

Extras

Chapter 1: Jane1. JANE

Outside the walls of the castle, standing before the moat, looking out at the stream that separates us from our subjects, there is a woman in a box. She is tall and blond. She has an ivory dress and pale skin and a shock of a red mouth. She doesn’t move. Not even when the townspeople wave and clamor for her attention. Not even now, when I am looking into her unblinking eyes. She doesn’t move. She can’t.

The woman is my mother.

I tell myself these facts every day, a story I repeat in my head. A true story that can feel untrue, which is why I find myself saying it over and over. My mother, the queen, is frozen in a box. We have to break the spell.

“What’d you say?” Olive says, pulling on one side of my dress, then the other, as if there is a perfect way to wear it, but my body isn’t cooperating. I must have said the words out loud. Years of hunger have broken down my defenses, and thoughts slip out too often now, forgetting to ask my permission first.

“We’re going to break the spell today,” I say, testing out the words for my attendant. They sound true enough. They sound possible, at least.

Olive pauses. Her hands are on my back, pulling and stitching fabric that was meant for someone softer, someone fuller, someone fed. It’s her job to make my dresses fit me, and that means her fingers are always calloused from the needle, her eyes always squinting from the delicacy of the work, the impossibility of making my body look anything but Spellbound. “I hope that’s true,” she says at last.

There’s a clatter from the dining room, one floor below us. I used to like this part of the castle. It always smells like whatever is cooking. And whatever is cooking is always delicious. Now it’s a pointed kind of torture, to smell everything I haven’t been able to eat for five years.

Dad’s offered to move me into a different room a hundred times, but it feels like admitting defeat, so I stay. “Queens don’t complain,” I’ve reminded him more than once. A lesson my mother taught me, when she was out here and not in that box.

“They’re having scones,” I say now, smelling the air. “Cherry.”

“Chocolate cherry,” Olive says before shaking her head and correcting herself. “I’m sorry. I don’t know why I said that. You don’t need to know that.”

“Chocolate-cherry scones,” I say. “Don’t know that I’ve ever had them.”

“For Eden’s birthday, whatever she requests is what gets made,” Olive says, repeating the rules to me as if they aren’t my own, as if I don’t live with them every day. Across the generations many things have happened on Thirteenth Birthdays. Engagements. Weddings. Treaties between nations. And of course, eighty years ago, a kidnapped princess, the start of the biggest War. The War We Won.

I’m begging tonight to matter the way so many other Thirteenth Birthdays have.

Downstairs, my sisters are laughing at something. I can practically hear their tongues in their mouths, their hands wiping their lips, their throats swallowing. It’s not just food I miss. It’s everything that comes with food. The way my father used to spread the butter on my bread for me, always caking on extra. The jokes at the table. The loveliness of a heavy silver fork in my hand. Even the way meals mark the passing of time, giving a long day balance and breaks.

Now a day is just an endless stretch of hunger that goes from dawn until dusk without a single breath of relief.

Even today.

“I think you’ll be able to break the spell,” Olive says, working on fitting the sleeves of my gown around my wrists. This dress fit fine a month ago, but it’s now swallowing me whole. The Slow Spell is Quickening. Time is running out.

Ever since the spell was cast, I’ve been counting down to Eden’s Thirteenth Birthday, when the witch promised she’d return to tell us how to break the spell before it turns True.

I wonder if the people of Ever have been thinking about it too. They cried the day the spell was cast. They watched from the other side of the moat when the witch appeared on the Grand Yard, arms raised, a cape flying out behind her. She was a young witch. My age. Her voice was thin as it recited a magical chant. She called out our fates one by one, telling us what malady would befall us on our Thirteenth Birthdays. “When you each reach my age,” she said, “that’s when the spell will bind you. On your Thirteenth Birthday. When it binds the last of you, in five years’ time on Princess Eden’s birthday, I’ll return. I’ll give you one chance to break the spell.”

I waited for Dad to react, to boom out a hundred questions. Most importantly, Why are you doing this? and Don’t you know what our agreement is? and maybe also Do the older witches know you’re here; are you confused; can someone fetch this young, unhinged witch and return her to her Home on the Hill?

Instead, he was quiet. We were all in shock. Witches were our partners in keeping Ever safe. We protected them. They protected us. Perfect symbiosis. Everything about this witch, from her age to her words to the spell itself, was wrong. More than wrong. Impossible.

I was shaking from the impossibility of it.

Mom was quiet too. Queens are quiet, and she was always, always a queen first.

I stayed quiet for as long as I could, because I wanted to be queen. But as long as I could turned out to be twenty-two seconds.

“Why would you do this?” I said. My voice was small at first, then louder, because she didn’t answer, and her face only got harder, more sure. “This is— What are you doing? We’re princesses, and you’re… We don’t do this to each other! Why would you do this?”

Mom had told me a hundred times that silence is more meaningful than words. I was failing at following Mom’s rules, but I didn’t know how to be quiet in the face of this witch.

The witch kept her mouth closed. She wouldn’t look at me. She looked everywhere else, though. She looked at the castle—its stone, its turrets, its incredible size.

I tried to say only the most important thing in the enormous valley of my parents’ silence. “Please,” I said. “No.”

“I have to,” she said. She looked a little sad saying it. Or maybe I’m just remembering it that way.

I was the oldest, three days from my Thirteenth Birthday. The rest of my sisters would have more time to prepare for the spell. Nora would have over a year. Alice another year beyond that. Grace would have nearly four years to think it all through. And Eden would have the whole five years. I had three days. My heart beat out the number. Three. Three. Three.

“Please,” I said again. “No.” Thirteenth Birthdays are celebrated with enormous royal balls, a feast, a dance, silk dresses, a silver crown. Not with curses. Mine was already all planned. “No,” I said again, trying to make it sound royal and right. “No.”

I looked at my mother. She would know how to fix it. My whole life, she’d solved every problem that had come my way.

There hadn’t been many.

I watched her body lean forward a little, her mouth form an O shape, about to say something wise and true to this young witch, ready to finally break her queenly silence. But before a word came out, before she could stitch things back together, make our world right again, she froze. A glass box appeared around her, trapping her inside.

She was Spellbound.

My heart spun right out of my body and joined her in that glass box. I didn’t cry or scream or throw myself onto the glass. Instead I buried my face in my arms and bent at the waist, like if I could get small and hidden enough, I could disappear from the moment.

She was not yet done teaching me how to be a queen, and I was immediately lost without her. I couldn’t think of words or find the right shape for my body to take. I ran through everything she’d ever told me about queens and witches and spells and How to Be. Queens don’t beg witches to be kind. Queens don’t let their eyes fill with tears or let their hearts beat out three, three, three. Queens don’t wish they weren’t the oldest princess; queens don’t wish their sisters would be hit by the spell first; queens don’t hate everyone who isn’t cursed.

I closed my eyes and told my heart to shut up. Queens are quiet.

I knew enough about witches to know that a thirteen-year-old witch could only cast a Slow Spell, the kind that didn’t have everlasting consequences. When witches turn eighteen, their spells turn True, permanent, everlasting, and damaging.

“How do we break the spell?” I asked, trying to find the right words for a queen to say, hoping my mother could hear me and be proud of me, even behind that layer of thick glass.

The witch’s eyes were steady and wide and gray. Her skin looked like mine—an uneven, patchy white. Her mouth was a surprising shade of red, like my mother’s. It is impossible to pick out a witch by anything but the skirts around their waists. In every other way, they look like the rest of Ever. Their skin is every shade of white or brown or in-between; their noses and eyes and chins take different shapes. They are tall and short and round and straight. They are mostly women, but there are witches across the gender spectrum. The only thing they always have in common is magic and the layers of fabric in all colors and textures and patterns tied around their waists, marking them, warning us.

“I’ll return in five years’ time,” the young witch said, repeating her earlier promise with no further details. It wasn’t what I wanted to hear. I wanted a new answer, a better spell, an easier curse.

Alice’s fingers found mine in the silence that followed. Nora drew closer to me. Mom in her glass box had a straight back and kind eyes. I tried to imitate her, but my knees kept buckling. Queens aren’t scared, I told my knees, but they didn’t listen. My mouth was dry. My head swam.

“Please,” Dad said. I had never heard my father beg for anything. He was the king, after all. If queens weren’t meant to beg, kings certainly weren’t either. I wrapped my arms around myself, as if that could hold me together. We were all falling apart.

The witch didn’t care about any of it. She didn’t tell us why. She just looked at us, at all of us, like we already knew.

“How do we break the spell?” I called out to her again, a question I’d already asked and she’d already answered. These were the only words I had. That, and three days. Three days. Three days.

“I’ll be back when the spell has bound the last of you,” the witch said again. With one more sorry look at me, the witch was gone and Mom was trapped, and three days later I turned thirteen and I wasn’t able to lift food or drink to my mouth. I wasn’t able to eat.

And finally, five years later, we are here. Eden’s birthday. Chocolate-cherry scones. A dress that doesn’t fit. A crowd of people across the moat, remembering or not remembering that we were not always Spellbound.

I don’t know when the witch will turn eighteen, when exactly the Slow Spell could turn True, as all unbroken Slow Spells do. But I hope it’s months from now, or maybe a whole year. We’ve studied the breaking of spells these past five years, and they can be complicated and dangerous to undo. Maybe we will be required to cut our hair and give up all our jewels or climb a mountain in another kingdom or solve a nearly impossible riddle. We may have to sit alone in a locked room for weeks or stand outside in the town square for a month without speaking. We might have to give up our castle, our attendants, our avocados, the summer months.

My stomach grips as I try to imagine what tonight will bring. I didn’t know it was possible to look forward to something and dread it all at once, but it is. I am. We are.

“I hope—” I start, but I have no idea how to finish the sentence. I want a hundred things I can’t have. “I hope—” I try again, but there’s no end; there’s nothing to say.

“I know,” Olive says. My father’s voice bellows from downstairs. He’s loud when he’s happy, and it seems to startle Olive. Her shoulders jump. “I hope too.”

My heart pounds, like it did all those years ago. My knees are weak again, weaker now, from lack of nourishment. And I want my mother more than I’ve ever wanted anything. I want her here, now, the way she should be. Smoothing my dress, suggesting hairstyles, telling me I look beautiful.

“I want to show my mother my dress,” I tell Olive, and she escorts me downstairs and out the door. I don’t go anywhere alone. Even when I’m sleeping, Olive checks in on me throughout the night, to make sure I’m safe and comfortable and the right temperature for a princess.

We don’t stop in the dining room, don’t greet my family. I don’t speak with them when they’re eating. It’s easier that way.

“Your Spellbound! Good morning!” a girl with brown skin and braided hair calls out from across the moat the second we are on the Grand Yard. We aren’t meant to speak directly to our subjects, and they know this. But they try anyway. I wave but say nothing.

“Your Stillness,” her white, rosy-cheeked friend booms to my mother in her glass box. “We miss you!”

Subjects say silly things from across the moat. It’s our job to let them. To smile and wave and say nothing. We stay on our side of the moat, and they stay on theirs. It’s how things are and how things have been and how they will always be.

A long time ago, before I was Spellbound, I wondered aloud what it would be like to walk in the kingdom that belongs to us, to know its streets and its people. But my mother and father assured me I did know Ever. “You don’t need to see every leaf in the forest to be the sun giving it the light to grow,” Dad said, and now I know that he’s right. Princesses stay in castles. Kings gives speeches from towers. Attendants say yes and bow their heads when the king enters and sometimes shake at the sight of him. We see Ever from here. That is enough, because it has always been enough.

What I don’t understand, what maybe no one understands, is witches. “They keep us at rest,” Mom said before she was rendered speechless in a box. “And we keep them safe. It’s an imperfect thing. Witches are imperfect. We are too. A queen needs to know that.” I nodded. She nodded back. Looked at me to make sure I was really hearing her. She didn’t need to look so hard, though. I always listened to my mother. “Anyway, it’s all we have. The imperfect agreement. It’s all they have too, after the War We Won. We’re all just waiting for the kidnapped princess to return.” She looked like she had more to say. She was speaking more quickly than usual, repeating herself to make sure I understood. “The witches help us wait.” She nodded to the candles across the moat, the ones our subjects keep lit at all times, so that the kidnapped princess can find her way back to us, someday. And she gestured to the rock carving of the kidnapped princess that Alice had made based on a photograph Dad had given her. She looks a little like me. Pointy chin, straight back, small nose, long hair.

I’m supposed to hope for the return of this princess, for solving the mystery of who took her, for knowing which kingdom, out of all the kingdoms, is actually the one that should be Banned. But I can’t hope for anything but the breaking of the spell.

“Do you like my dress?” I ask my mother, holding up the corners of the gown that now more or less fits me. It’s an icy pale blue and is embroidered with jewels. “I wanted something special for Eden’s Thirteenth Birthday,” I say. “Olive made it.” Olive stands a few yards away from my mother and me. She knows when to be close and when to give me space. She knows what I need more than I do, sometimes.

What I need right now, though, is my mother’s kind smile and her bright eyes. I want her to tell me I look like a queen, finally, because the last time she spoke to me, I was so young and so silly and so unstudied.

“The dress is fine, Jane,” my sister Nora says from her spot on the lawn. I don’t know when she joined me out here. She’s sneaky, Nora. Quiet when she wants to be and never wasting time with things like saying good morning or asking how I’m doing. She has hitched her skirts up to her knees and is letting the sun freckle her skin. “Who cares what you look like anyway. This isn’t exactly the party where you’re going to meet the love of your life.”

Her mouth sort of folds over the word “love,” like it’s a joke. And I guess for her it is. The same spell that cursed me with not eating cursed her with not loving. She can’t feel any kind of love—not for princes or princesses or dukes or duchesses, which wouldn’t be so unusual. But Nora can’t feel any love for us, either, not for her family, or her subjects, or the small blue birds she used to feed bread crumbs to, and not even for herself. I suppose for Nora, love sounds about as attainable as a roast chicken does to me.

“Thirteenth Birthdays were Mom’s favorite,” I say. Nora and I remember her best. Alice, Grace, and Eden guess at who she is and what she loved and what she used to say. But Nora and I recall the specifics—the way her hair knotted in the wind, the way she held her hands to her heart when she was disappointed, the care with which she shrugged into a new ball gown like it was a second skin. “She said a Thirteenth Birthday marks the moment a princess becomes herself.”

The day the spell was cast was so close to my own Thirteenth Birthday that preparations had been well underway. Mom and I had chosen the ocean as a theme. I’ve never seen one, but I was fascinated by the idea of an expanse of water so large you couldn’t see the other side. My Thirteenth Birthday was going to have seafood entrées and waves of water beneath glass floors and the smell of salt in the air. The witches had agreed to help make it so. Olive made me an ocean dress in blues and greens, waves of fabric that swished and swayed with such force I could have imagined I was caught in a tide’s pull.

But when it was time for my Thirteenth Birthday, I spent it in a corner, and I called Olive ridiculous for making the gown. I refused to eat a last meal. If I think too hard now, I can still feel the pain of it. How good it felt to topple a tray of bonbons. How I wanted to punch my hand through a window or kick a prince.

It’s there even now, deep down. A simmering rage I’m barely holding back.

Nora knows it too. We are both thinking about last year’s party for Grace. And two years before that when Alice turned thirteen. A royal Thirteenth Birthday used to be a joyous moment, introducing a princess to her future. She’d meet princes and princesses from other kingdoms. She would be given a silver-and-emerald crown. She would be given a title. Princess Mara the Clever. Princess Emily the Listening. Princess Betsy the Strong.

Now we are given our spell and nothing else. Princess Jane Who Can’t Eat. Princess Nora Who Can’t Love. Princess Alice Who Can’t Sleep. Princess Grace Who Can’t Remember. Princess Eden Who Can’t Hope.

“Who cares about Birthdays and dresses?” Nora asks. “Who cares about any of this?”

I’d be better off ignoring Nora, but I can’t. She’s so present. Her body looks the way mine used to—thick around the hips, rounded at the breasts, at the belly. Sturdy and sweet.

I squeeze my hands into fists and wonder what it would be like to shove her, hard, against a tree.

What would a queen do? my mind interrupts. Be a queen. I pull my shoulders back and lift my chin and take on the pose of a ruler.

Nora raises her eyebrows at the way the lace of my dress drapes, clings, tries to thicken me up, fails. Because the spell is a Slow one, I can’t waste away entirely, I can’t die of starvation, but I can’t imagine getting any skinnier than I am right now. I suppose that makes sense. One way or another, we are near the end.

I push the thought away. You will be queen. I will not die from this spell.

“Mom loved the food at the Thirteenth Birthdays,” Nora says. I can’t tell if it’s meant to be cruel or matter-of-fact. I don’t think Nora knows either.

“The only taste I remember is apple,” I say.

“Apple, huh?” Nora says. She stands up, and her dress falls down around her, a mint-green cloud.

“It’s sweet,” I say, licking my lips like some phantom taste might still be there. “Tangy. Watery. A pinch of a taste. The kind of thing you could eat for hours and never feel full from. Is that right?”

“That’s about right,” Nora says with a sort of smile. “The Prince of Soar loves apples. Dad told me. The chef will be making them baked with cinnamon for him.”

“He’s the redheaded one?” I ask.

She shakes her head. “No, that’s the Prince of Nethering. The Prince of Soar is the tall one. Glasses. Dimples. Soft voice.”

I nod. It’s hard to keep track of these things. When I was allowed to eat, names and faces and locations felt like distinct, graspable ideas. Now it’s all hazy, and my anger keeps rising and rising, obscuring things even more.

Be a queen, I tell myself again. I try to stay still and silent. It’s harder than it sounds.

I remember reciting the Royal Rules with my mother before bed every night. I loved the rules. If I could follow them, I would be queen, and all would be well. At rest. The way it was meant to be. I can almost hear my mother’s small voice singing its way through the long list of things I was supposed to be.

Then the moment’s over, and she’s just a woman in glass again, just a trapped queen, just someone I used to know.

Once upon a time.

Outside the walls of the castle, standing before the moat, looking out at the stream that separates us from our subjects, there is a woman in a box. She is tall and blond. She has an ivory dress and pale skin and a shock of a red mouth. She doesn’t move. Not even when the townspeople wave and clamor for her attention. Not even now, when I am looking into her unblinking eyes. She doesn’t move. She can’t.

The woman is my mother.

I tell myself these facts every day, a story I repeat in my head. A true story that can feel untrue, which is why I find myself saying it over and over. My mother, the queen, is frozen in a box. We have to break the spell.

“What’d you say?” Olive says, pulling on one side of my dress, then the other, as if there is a perfect way to wear it, but my body isn’t cooperating. I must have said the words out loud. Years of hunger have broken down my defenses, and thoughts slip out too often now, forgetting to ask my permission first.

“We’re going to break the spell today,” I say, testing out the words for my attendant. They sound true enough. They sound possible, at least.

Olive pauses. Her hands are on my back, pulling and stitching fabric that was meant for someone softer, someone fuller, someone fed. It’s her job to make my dresses fit me, and that means her fingers are always calloused from the needle, her eyes always squinting from the delicacy of the work, the impossibility of making my body look anything but Spellbound. “I hope that’s true,” she says at last.

There’s a clatter from the dining room, one floor below us. I used to like this part of the castle. It always smells like whatever is cooking. And whatever is cooking is always delicious. Now it’s a pointed kind of torture, to smell everything I haven’t been able to eat for five years.

Dad’s offered to move me into a different room a hundred times, but it feels like admitting defeat, so I stay. “Queens don’t complain,” I’ve reminded him more than once. A lesson my mother taught me, when she was out here and not in that box.

“They’re having scones,” I say now, smelling the air. “Cherry.”

“Chocolate cherry,” Olive says before shaking her head and correcting herself. “I’m sorry. I don’t know why I said that. You don’t need to know that.”

“Chocolate-cherry scones,” I say. “Don’t know that I’ve ever had them.”

“For Eden’s birthday, whatever she requests is what gets made,” Olive says, repeating the rules to me as if they aren’t my own, as if I don’t live with them every day. Across the generations many things have happened on Thirteenth Birthdays. Engagements. Weddings. Treaties between nations. And of course, eighty years ago, a kidnapped princess, the start of the biggest War. The War We Won.

I’m begging tonight to matter the way so many other Thirteenth Birthdays have.

Downstairs, my sisters are laughing at something. I can practically hear their tongues in their mouths, their hands wiping their lips, their throats swallowing. It’s not just food I miss. It’s everything that comes with food. The way my father used to spread the butter on my bread for me, always caking on extra. The jokes at the table. The loveliness of a heavy silver fork in my hand. Even the way meals mark the passing of time, giving a long day balance and breaks.

Now a day is just an endless stretch of hunger that goes from dawn until dusk without a single breath of relief.

Even today.

“I think you’ll be able to break the spell,” Olive says, working on fitting the sleeves of my gown around my wrists. This dress fit fine a month ago, but it’s now swallowing me whole. The Slow Spell is Quickening. Time is running out.

Ever since the spell was cast, I’ve been counting down to Eden’s Thirteenth Birthday, when the witch promised she’d return to tell us how to break the spell before it turns True.

I wonder if the people of Ever have been thinking about it too. They cried the day the spell was cast. They watched from the other side of the moat when the witch appeared on the Grand Yard, arms raised, a cape flying out behind her. She was a young witch. My age. Her voice was thin as it recited a magical chant. She called out our fates one by one, telling us what malady would befall us on our Thirteenth Birthdays. “When you each reach my age,” she said, “that’s when the spell will bind you. On your Thirteenth Birthday. When it binds the last of you, in five years’ time on Princess Eden’s birthday, I’ll return. I’ll give you one chance to break the spell.”

I waited for Dad to react, to boom out a hundred questions. Most importantly, Why are you doing this? and Don’t you know what our agreement is? and maybe also Do the older witches know you’re here; are you confused; can someone fetch this young, unhinged witch and return her to her Home on the Hill?

Instead, he was quiet. We were all in shock. Witches were our partners in keeping Ever safe. We protected them. They protected us. Perfect symbiosis. Everything about this witch, from her age to her words to the spell itself, was wrong. More than wrong. Impossible.

I was shaking from the impossibility of it.

Mom was quiet too. Queens are quiet, and she was always, always a queen first.

I stayed quiet for as long as I could, because I wanted to be queen. But as long as I could turned out to be twenty-two seconds.

“Why would you do this?” I said. My voice was small at first, then louder, because she didn’t answer, and her face only got harder, more sure. “This is— What are you doing? We’re princesses, and you’re… We don’t do this to each other! Why would you do this?”

Mom had told me a hundred times that silence is more meaningful than words. I was failing at following Mom’s rules, but I didn’t know how to be quiet in the face of this witch.

The witch kept her mouth closed. She wouldn’t look at me. She looked everywhere else, though. She looked at the castle—its stone, its turrets, its incredible size.

I tried to say only the most important thing in the enormous valley of my parents’ silence. “Please,” I said. “No.”

“I have to,” she said. She looked a little sad saying it. Or maybe I’m just remembering it that way.

I was the oldest, three days from my Thirteenth Birthday. The rest of my sisters would have more time to prepare for the spell. Nora would have over a year. Alice another year beyond that. Grace would have nearly four years to think it all through. And Eden would have the whole five years. I had three days. My heart beat out the number. Three. Three. Three.

“Please,” I said again. “No.” Thirteenth Birthdays are celebrated with enormous royal balls, a feast, a dance, silk dresses, a silver crown. Not with curses. Mine was already all planned. “No,” I said again, trying to make it sound royal and right. “No.”

I looked at my mother. She would know how to fix it. My whole life, she’d solved every problem that had come my way.

There hadn’t been many.

I watched her body lean forward a little, her mouth form an O shape, about to say something wise and true to this young witch, ready to finally break her queenly silence. But before a word came out, before she could stitch things back together, make our world right again, she froze. A glass box appeared around her, trapping her inside.

She was Spellbound.

My heart spun right out of my body and joined her in that glass box. I didn’t cry or scream or throw myself onto the glass. Instead I buried my face in my arms and bent at the waist, like if I could get small and hidden enough, I could disappear from the moment.

She was not yet done teaching me how to be a queen, and I was immediately lost without her. I couldn’t think of words or find the right shape for my body to take. I ran through everything she’d ever told me about queens and witches and spells and How to Be. Queens don’t beg witches to be kind. Queens don’t let their eyes fill with tears or let their hearts beat out three, three, three. Queens don’t wish they weren’t the oldest princess; queens don’t wish their sisters would be hit by the spell first; queens don’t hate everyone who isn’t cursed.

I closed my eyes and told my heart to shut up. Queens are quiet.

I knew enough about witches to know that a thirteen-year-old witch could only cast a Slow Spell, the kind that didn’t have everlasting consequences. When witches turn eighteen, their spells turn True, permanent, everlasting, and damaging.

“How do we break the spell?” I asked, trying to find the right words for a queen to say, hoping my mother could hear me and be proud of me, even behind that layer of thick glass.

The witch’s eyes were steady and wide and gray. Her skin looked like mine—an uneven, patchy white. Her mouth was a surprising shade of red, like my mother’s. It is impossible to pick out a witch by anything but the skirts around their waists. In every other way, they look like the rest of Ever. Their skin is every shade of white or brown or in-between; their noses and eyes and chins take different shapes. They are tall and short and round and straight. They are mostly women, but there are witches across the gender spectrum. The only thing they always have in common is magic and the layers of fabric in all colors and textures and patterns tied around their waists, marking them, warning us.

“I’ll return in five years’ time,” the young witch said, repeating her earlier promise with no further details. It wasn’t what I wanted to hear. I wanted a new answer, a better spell, an easier curse.

Alice’s fingers found mine in the silence that followed. Nora drew closer to me. Mom in her glass box had a straight back and kind eyes. I tried to imitate her, but my knees kept buckling. Queens aren’t scared, I told my knees, but they didn’t listen. My mouth was dry. My head swam.

“Please,” Dad said. I had never heard my father beg for anything. He was the king, after all. If queens weren’t meant to beg, kings certainly weren’t either. I wrapped my arms around myself, as if that could hold me together. We were all falling apart.

The witch didn’t care about any of it. She didn’t tell us why. She just looked at us, at all of us, like we already knew.

“How do we break the spell?” I called out to her again, a question I’d already asked and she’d already answered. These were the only words I had. That, and three days. Three days. Three days.

“I’ll be back when the spell has bound the last of you,” the witch said again. With one more sorry look at me, the witch was gone and Mom was trapped, and three days later I turned thirteen and I wasn’t able to lift food or drink to my mouth. I wasn’t able to eat.

And finally, five years later, we are here. Eden’s birthday. Chocolate-cherry scones. A dress that doesn’t fit. A crowd of people across the moat, remembering or not remembering that we were not always Spellbound.

I don’t know when the witch will turn eighteen, when exactly the Slow Spell could turn True, as all unbroken Slow Spells do. But I hope it’s months from now, or maybe a whole year. We’ve studied the breaking of spells these past five years, and they can be complicated and dangerous to undo. Maybe we will be required to cut our hair and give up all our jewels or climb a mountain in another kingdom or solve a nearly impossible riddle. We may have to sit alone in a locked room for weeks or stand outside in the town square for a month without speaking. We might have to give up our castle, our attendants, our avocados, the summer months.

My stomach grips as I try to imagine what tonight will bring. I didn’t know it was possible to look forward to something and dread it all at once, but it is. I am. We are.

“I hope—” I start, but I have no idea how to finish the sentence. I want a hundred things I can’t have. “I hope—” I try again, but there’s no end; there’s nothing to say.

“I know,” Olive says. My father’s voice bellows from downstairs. He’s loud when he’s happy, and it seems to startle Olive. Her shoulders jump. “I hope too.”

My heart pounds, like it did all those years ago. My knees are weak again, weaker now, from lack of nourishment. And I want my mother more than I’ve ever wanted anything. I want her here, now, the way she should be. Smoothing my dress, suggesting hairstyles, telling me I look beautiful.

“I want to show my mother my dress,” I tell Olive, and she escorts me downstairs and out the door. I don’t go anywhere alone. Even when I’m sleeping, Olive checks in on me throughout the night, to make sure I’m safe and comfortable and the right temperature for a princess.

We don’t stop in the dining room, don’t greet my family. I don’t speak with them when they’re eating. It’s easier that way.

“Your Spellbound! Good morning!” a girl with brown skin and braided hair calls out from across the moat the second we are on the Grand Yard. We aren’t meant to speak directly to our subjects, and they know this. But they try anyway. I wave but say nothing.

“Your Stillness,” her white, rosy-cheeked friend booms to my mother in her glass box. “We miss you!”

Subjects say silly things from across the moat. It’s our job to let them. To smile and wave and say nothing. We stay on our side of the moat, and they stay on theirs. It’s how things are and how things have been and how they will always be.

A long time ago, before I was Spellbound, I wondered aloud what it would be like to walk in the kingdom that belongs to us, to know its streets and its people. But my mother and father assured me I did know Ever. “You don’t need to see every leaf in the forest to be the sun giving it the light to grow,” Dad said, and now I know that he’s right. Princesses stay in castles. Kings gives speeches from towers. Attendants say yes and bow their heads when the king enters and sometimes shake at the sight of him. We see Ever from here. That is enough, because it has always been enough.

What I don’t understand, what maybe no one understands, is witches. “They keep us at rest,” Mom said before she was rendered speechless in a box. “And we keep them safe. It’s an imperfect thing. Witches are imperfect. We are too. A queen needs to know that.” I nodded. She nodded back. Looked at me to make sure I was really hearing her. She didn’t need to look so hard, though. I always listened to my mother. “Anyway, it’s all we have. The imperfect agreement. It’s all they have too, after the War We Won. We’re all just waiting for the kidnapped princess to return.” She looked like she had more to say. She was speaking more quickly than usual, repeating herself to make sure I understood. “The witches help us wait.” She nodded to the candles across the moat, the ones our subjects keep lit at all times, so that the kidnapped princess can find her way back to us, someday. And she gestured to the rock carving of the kidnapped princess that Alice had made based on a photograph Dad had given her. She looks a little like me. Pointy chin, straight back, small nose, long hair.

I’m supposed to hope for the return of this princess, for solving the mystery of who took her, for knowing which kingdom, out of all the kingdoms, is actually the one that should be Banned. But I can’t hope for anything but the breaking of the spell.

“Do you like my dress?” I ask my mother, holding up the corners of the gown that now more or less fits me. It’s an icy pale blue and is embroidered with jewels. “I wanted something special for Eden’s Thirteenth Birthday,” I say. “Olive made it.” Olive stands a few yards away from my mother and me. She knows when to be close and when to give me space. She knows what I need more than I do, sometimes.

What I need right now, though, is my mother’s kind smile and her bright eyes. I want her to tell me I look like a queen, finally, because the last time she spoke to me, I was so young and so silly and so unstudied.

“The dress is fine, Jane,” my sister Nora says from her spot on the lawn. I don’t know when she joined me out here. She’s sneaky, Nora. Quiet when she wants to be and never wasting time with things like saying good morning or asking how I’m doing. She has hitched her skirts up to her knees and is letting the sun freckle her skin. “Who cares what you look like anyway. This isn’t exactly the party where you’re going to meet the love of your life.”

Her mouth sort of folds over the word “love,” like it’s a joke. And I guess for her it is. The same spell that cursed me with not eating cursed her with not loving. She can’t feel any kind of love—not for princes or princesses or dukes or duchesses, which wouldn’t be so unusual. But Nora can’t feel any love for us, either, not for her family, or her subjects, or the small blue birds she used to feed bread crumbs to, and not even for herself. I suppose for Nora, love sounds about as attainable as a roast chicken does to me.

“Thirteenth Birthdays were Mom’s favorite,” I say. Nora and I remember her best. Alice, Grace, and Eden guess at who she is and what she loved and what she used to say. But Nora and I recall the specifics—the way her hair knotted in the wind, the way she held her hands to her heart when she was disappointed, the care with which she shrugged into a new ball gown like it was a second skin. “She said a Thirteenth Birthday marks the moment a princess becomes herself.”

The day the spell was cast was so close to my own Thirteenth Birthday that preparations had been well underway. Mom and I had chosen the ocean as a theme. I’ve never seen one, but I was fascinated by the idea of an expanse of water so large you couldn’t see the other side. My Thirteenth Birthday was going to have seafood entrées and waves of water beneath glass floors and the smell of salt in the air. The witches had agreed to help make it so. Olive made me an ocean dress in blues and greens, waves of fabric that swished and swayed with such force I could have imagined I was caught in a tide’s pull.

But when it was time for my Thirteenth Birthday, I spent it in a corner, and I called Olive ridiculous for making the gown. I refused to eat a last meal. If I think too hard now, I can still feel the pain of it. How good it felt to topple a tray of bonbons. How I wanted to punch my hand through a window or kick a prince.

It’s there even now, deep down. A simmering rage I’m barely holding back.

Nora knows it too. We are both thinking about last year’s party for Grace. And two years before that when Alice turned thirteen. A royal Thirteenth Birthday used to be a joyous moment, introducing a princess to her future. She’d meet princes and princesses from other kingdoms. She would be given a silver-and-emerald crown. She would be given a title. Princess Mara the Clever. Princess Emily the Listening. Princess Betsy the Strong.

Now we are given our spell and nothing else. Princess Jane Who Can’t Eat. Princess Nora Who Can’t Love. Princess Alice Who Can’t Sleep. Princess Grace Who Can’t Remember. Princess Eden Who Can’t Hope.

“Who cares about Birthdays and dresses?” Nora asks. “Who cares about any of this?”

I’d be better off ignoring Nora, but I can’t. She’s so present. Her body looks the way mine used to—thick around the hips, rounded at the breasts, at the belly. Sturdy and sweet.

I squeeze my hands into fists and wonder what it would be like to shove her, hard, against a tree.

What would a queen do? my mind interrupts. Be a queen. I pull my shoulders back and lift my chin and take on the pose of a ruler.

Nora raises her eyebrows at the way the lace of my dress drapes, clings, tries to thicken me up, fails. Because the spell is a Slow one, I can’t waste away entirely, I can’t die of starvation, but I can’t imagine getting any skinnier than I am right now. I suppose that makes sense. One way or another, we are near the end.

I push the thought away. You will be queen. I will not die from this spell.

“Mom loved the food at the Thirteenth Birthdays,” Nora says. I can’t tell if it’s meant to be cruel or matter-of-fact. I don’t think Nora knows either.

“The only taste I remember is apple,” I say.

“Apple, huh?” Nora says. She stands up, and her dress falls down around her, a mint-green cloud.

“It’s sweet,” I say, licking my lips like some phantom taste might still be there. “Tangy. Watery. A pinch of a taste. The kind of thing you could eat for hours and never feel full from. Is that right?”

“That’s about right,” Nora says with a sort of smile. “The Prince of Soar loves apples. Dad told me. The chef will be making them baked with cinnamon for him.”

“He’s the redheaded one?” I ask.

She shakes her head. “No, that’s the Prince of Nethering. The Prince of Soar is the tall one. Glasses. Dimples. Soft voice.”

I nod. It’s hard to keep track of these things. When I was allowed to eat, names and faces and locations felt like distinct, graspable ideas. Now it’s all hazy, and my anger keeps rising and rising, obscuring things even more.

Be a queen, I tell myself again. I try to stay still and silent. It’s harder than it sounds.

I remember reciting the Royal Rules with my mother before bed every night. I loved the rules. If I could follow them, I would be queen, and all would be well. At rest. The way it was meant to be. I can almost hear my mother’s small voice singing its way through the long list of things I was supposed to be.

Then the moment’s over, and she’s just a woman in glass again, just a trapped queen, just someone I used to know.

Once upon a time.

Descriere

Incisive and lyrical feminist fairy tale about a princess determined to save her sisters from a curse, even if it means allying herself with the very witch who cast it.