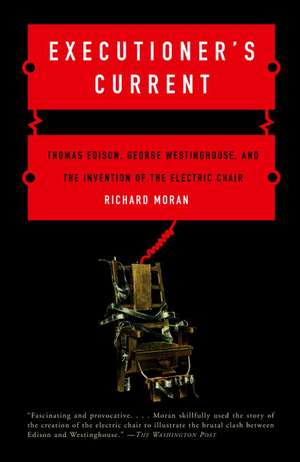

Executioner's Current: Thomas Edison, George Westinghouse, and the Invention of the Electric Chair

Autor Richard Moranen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2003

In 1882, Thomas Edison ushered in the “age of electricity” when he illuminated Manhattan’s Pearl Street with his direct current (DC) system. Six years later, George Westinghouse lit up Buffalo with his less expensive alternating current (AC). The two men quickly became locked in a fierce rivalry, made all the more complicated by a novel new application for their product: the electric chair. When Edison set out to persuade the state of New York to use Westinghouse’s current to execute condemned criminals, Westinghouse fought back in court, attempting to stop the first electrocution and keep AC from becoming the “executioner’s current.” In this meticulously researched account of the ensuing legal battle and the horribly botched first execution, Moran raises disturbing questions not only about electrocution, but about about our society’s tendency to rely on new technologies to answer moral questions.

Preț: 86.49 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 130

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.55€ • 17.13$ • 13.99£

16.55€ • 17.13$ • 13.99£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375724466

ISBN-10: 037572446X

Pagini: 271

Ilustrații: 22 ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 037572446X

Pagini: 271

Ilustrații: 22 ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Richard Moran is professor of sociology at Mount Holyoke College and the author of Knowing Right from Wrong: The Insanity Defense of Daniel McNaughtan and numerous articles and reviews. He has also served as a commentator for National Public Radio’s Morning Edition and written op-eds for the Boston Globe, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, Chicago Tribune, Christian Science Monitor, New York Times, Newsweek, and The Wall Street Journal. He lives in South Hadley, Massachusetts.

Extras

ChapterOone

"William, It Is Time"

In the predawn hours of August 6, 1890, twenty-seven men of law, science, and medicine left their lodgings at the Osborne House and quietly made their way down State Street toward Auburn Penitentiary. It was a dull and gloomy morning with a few wet clouds in the sky. The night before had not been an easy one, and the results were written on the faces of each hunched figure. As the men walked, there was little conversation. Nearing the prison, they encountered a crowd of nearly five hundred spectators. Every tree and rooftop surrounding the ivy-covered stone prison was filled with expectant faces, and young men and boys were perched atop telegraph poles, eager to catch a glimpse of the condemned man scarcely visible through the narrow window of his lighted cell. Western Union had opened a temporary office across from the penitentiary in the dimly lit freight room of the New York Central railroad station. Inside, newspapermen and telegraph operators anxiously waited to dispatch word around the world that the first execution by electricity had taken place.

Although a ticket of admission had been issued to each witness, the men had difficulty gaining entrance to the prison. The crowd was reluctant to give way and security was tight. Warden Charles Durston had ordered the gatekeeper not to let anyone in without a ticket; one witness who had forgotten his was forced to return to the hotel to fetch it. Even the morning shift of guards was not permitted to enter the prison until the bells rang, signifying a completed execution. District Attorney George Quinby, who had prosecuted the condemned man, looked pale as he walked through the prison gate below the statue of the Continental soldier standing guard on its roof. Though he had convicted many murderers, he had never witnessed an execution.

Once inside, the men were escorted into Warden Durston's office where prisoners in white caps and aprons served them coffee and sandwiches. Warden Durston did not join his distinguished guests for breakfast. He had gone directly from his prison lodgings to the basement cell of William Kemmler, the condemned man. After an exchange of pleasantries, Warden Durston drew an official, impressive-looking document from his breast pocket, for the law required that the death warrant be read prior to execution. For his part, Kemmler remained outwardly calm. "William, it is time," said the warden. "I am ready, Mr. Durston," the condemned man responded. Then the warden, his voice trembling, read the death warrant. It differed from all previous warrants only in the prescribed method of execution. William Kemmler was to receive a current of electricity sufficient to cause death.

Kemmler listened in resolute silence. When Warden Durston finished, the condemned man replied: "All right, I am ready." The two men then sat on Kemmler's iron bunk and spoke for a few moments before Durston returned to his office on the second floor. In the entranceway he met the witnesses, now standing about, waiting. They exchanged polite nods, nothing more. The atmosphere was decidedly funereal, although the condemned man was not yet dead.

During the previous afternoon, Warden Durston had shown the witnesses the newly constructed death chamber, where electricians were putting the finishing touches on the execution apparatus. Dr. George E. Fell, a Buffalo professor who had played an important role in the chair's final design, volunteered to be strapped into it for purpose of demonstration. As he did so, Warden Durston declared his utmost confidence in the reliability of the chair. Not everyone shared this optimistic assessment: specifically, some experts had doubts about the strength and dependability of the first-ever electric chair, but ultimately, they decided it was too late to make changes. The chair, they claimed, was indeed the perfect example of science employed for the betterment of humanity-death would be quick and painless.

From the time of his arrest for the murder of his paramour, Matilda "Tillie" Ziegler, on March 29, 1889, until four days after he was sentenced to death, Kemmler remained in the Erie County jail at Buffalo. Then, in accordance with the law, he was transferred to Auburn State Prison. During the trip, Kemmler told his keepers that years before an elderly fortune-teller in Philadelphia had foretold his execution, and everything had transpired exactly as she had predicted. Five days later, on the night of May 23, Kemmler was placed in solitary confinement. He was allowed no visitors except his keepers, his lawyers, his religious advisers, and a few friends of the warden.

About three months prior to his execution, Kemmler dictated his last will and testament to the head turnkey, guard James Warner. The men were interrupted several times by the sound of hammering from two convicts working nearby on the plain pine box that would serve as Kemmler's coffin. Electrician Edwin F. Davis, who would continue as an executioner for the next twenty-four years-throwing the switch on 240 condemned men-could be heard installing the execution apparatus in the room adjacent to Kemmler's cell. Seemingly indifferent to his impending execution, Kemmler assigned his meager belongings with great care. He designated that his principal keeper, Daniel McNaughton, should receive a pictorial Bible that had provided great solace to Kemmler. To the Reverend Dr. W. E. Houghton he left a pig-in-the-clover puzzle. He gave a slate with his autograph to prison chaplain Horatio Yates. To keeper William Wemple he left a small Bible. To Mrs. Durston, the warden's wife, Kemmler gave fifty autographed cards. While in confinement, Kemmler had learned to write his name. He was very proud of this accomplishment, and presumably wanted to share it with the woman who had taught him. He also believed that after his death, the cards would be of significant monetary value.

Kemmler distrusted reporters and had always refused to answer their questions. But he was talkative with visitors, and at times quite entertaining. "He sings, cracks jokes, and . . . tells stories-the sort of stories that wouldn't look well in print," reported the Buffalo Evening News. The paper stated blithely that there was a second reason the ax murderer should be executed: "He is a bad rhymester."

While in jail Kemmler composed several drinking songs, such as this one, published in the Buffalo Evening News.

I used to live in Buffalo,

The people knew me well,

I used to go a-peddling,

A plenty did I sell.

My old clothes were ragged and torn,

My shoes wouldn't cover my toes.

My old hat went flippity flap

With a schuper to my nose.

I can't sing sing,

I won't sing sing,

I'll tell you the reason why.

I can't sing sing,

I won't sing sing,

For my whistle is getting dry.

Despite the condemned man's penchant for ribaldry, Sheriff Oliver A. Jenkins reported that Kemmler was a model prisoner. Head turnkey Warner credited Kemmler with "bearing up wonderfully well" under the constant strain of imminent death.

When he arrived at Auburn on May 24, 1889, Kemmler was an habitual cigar smoker in poor physical condition, and of a "morose" and "taciturn" disposition. While at Auburn, however, Kemmler's personal health and appearance improved greatly. He attributed this change to his enforced temperance and claimed that while in the Erie County jail awaiting trial, the guards had constantly given him tobacco and whiskey. In the months prior to his execution, he was neatly dressed and his collar was turned up in accordance with the latest fashion. His whiskers were trimmed and parted at the chin in the English style, and he always wore a black tie. During his long confinement, Kemmler's health remained good, except for a brief bout with dysentery. He passed his time by singing banjo songs with fellow death row inmate Frank Fish, and listening to his keeper read Victor Hugo's Les Misèrables.

During Kemmler's long wait on death row, the warden's wife took a special interest in him. Mrs. Durston spent considerable time with Kemmler, singing, reading Scripture, or praying with him. By the end, Kemmler appeared a better man thanks to her intervention. Under her guidance he had learned to read, and seemed to have made peace with his Maker. In a way, all the loving attention devoted to him was compensation for being the first victim of a deadly scientific experiment. The last time she spoke with Kemmler, Mrs. Durston told him he was going to a better place. She took his hand and said, "God be with you, be brave, be strong; everything will come out right."

Mrs. Durston left town for New York City the next morning. Upon her arrival, a friend met her at the railroad station and took her to a country home in Lawrence, on Long Island. Her long association with Kemmler and her genuine concern for his well-being made it too difficult for her to remain in Auburn during the execution. The citizens of Auburn, kept in the dark as to the exact date of Kemmler's execution, naturally took Mrs. Durston's departure as a sign that the fatal day was at hand.

There remained only one possible source of delay. Some observers speculated that the electrical manufacturing giant George Westinghouse might, at the last minute, get an injunction to prevent the use of Westinghouse dynamos in the execution. Attorneys for the Westinghouse Company had fought Kemmler's execution on constitutional grounds right

up to the New York Supreme Court, but since the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear its appeal, there seemed little chance that an injunction would be granted. Although the Westinghouse attorneys had argued that electrocution was cruel and unusual punishment, their real concern was the inevitable association the public would make between death by electricity and its energy source, the alternating current produced by Westinghouse dynamos (generators).

To this end, Westinghouse's attorneys filed a writ for the return of the company dynamos. The writ of replevin claimed that Harold Brown, the electrician who prepared the execution apparatus, fraudulently obtained the dynamos. Westinghouse attorneys argued unsuccessfully that Westinghouse retained an interest in its dynamos even after they were sold, giving them control over any potential misuse.

Initially, Kemmler was sentenced to die during the week of June 24, 1889. To allow his attorneys time to pursue appeals, Kemmler was twice granted a stay of execution. Finally, on July 11, 1890, his legal means of recourse exhausted, William Kemmler arrived in a Buffalo courtroom to hear the sentence of death pronounced for the third time. Accompanied by his keeper, Daniel McNaughton, Kemmler was dressed in an impeccably pressed gray suit and a black derby hat. While confined at Auburn, his dark brown beard and mustache had grown thicker. During his trial, he looked listless and confused. On this day, he was alert, yet he appeared unconcerned. Judge Henry Childs of the New York Supreme Court asked the assistant district attorney if he had any business before the court.

"If the court please," he said, "we desire to move sentence on William Kemmler."

Kemmler was asked to stand up, and Judge Childs informed him that all attempts to save his life had failed. "Yes, sir," Kemmler replied. "Have you anything to say, why a time should not be fixed for carrying out the sentence previously passed upon you?" the judge asked. After a long pause, Kemmler responded, "No, sir." The judge said he hoped the prolonged delay had given Kemmler time to think about the enormity of his crime and the justice of his conviction. He then said that the sentence would be carried out during the week of August 4, 1890. The judge concluded with the time-honored phrase, "May God have mercy upon you."

Upon his return to Auburn prison, Kemmler appeared to be in good spirits, even though he had less than two weeks to live. He no longer spent as much time with his Bible, but preferred to have novels read to him by keeper McNaughton. Kemmler often made the cryptic remark that he "would never die by electricity"; apparently he still hoped for a last-minute reprieve. Along with fellow death row inmate and convicted murderer Frank Fish, who occupied the cell adjacent to Kemmler's, he joined in the daily activities with the "utmost relish." Like Kemmler, Fish was also confident that he would not die in the electric chair. Fish seemed to be in extraordinarily good spirits, even though, at best, a reprieve from the governor would still mean that he would spend the rest of his life in prison.

Until this point, it looked as if Joseph Chapleau, a poor French-Canadian farmer who had beaten his neighbor to death with a billet of wood, would be the first to go. However, on July 16, 1890, just four days before his scheduled execution, Governor David B. Hill commuted Chapleau's death sentence to life imprisonment. The electric chair had been installed at Dannemora Prison, the place of Chapleau's confinement and scheduled execution. Now it would have to be dismantled and moved to Auburn. William Francis Kemmler would go first.

The news that Kemmler would be first came as a shock to prison officials at Auburn. It was generally known that Warden Durston did not want to preside over the first electrical execution and would avoid it if possible. Durston had hoped to benefit from the experience gained at Dannemora, and he did not want to conduct what many regarded as a risky scientific experiment.Indeed, when Durston traveled to New York City four days before the execution, most people believed he went to persuade Governor David B. Hill that Kemmler had gone insane, requiring postponement of the execution. When Durston returned to Auburn, he remained in his office, refusing to talk with anyone.

The impending execution of William Kemmler was the major topic of conversation among the citizens of Auburn. The town was full of rumors concerning Kemmler's fate, the most significant being that Kemmler had lost his mind. If this were true, it would entitle him to a stay of execution and a commutation of his sentence to life imprisonment. However, the general impression was that Kemmler's lawyers had invented the ruse to save him from the executioner's current. According to his keepers, Kemmler's physical and mental condition was about what it had been on the day he was arrested for the murder of Tillie Ziegler. Jailer McNaughton, annoyed by the persistent rumors, remarked that despite his year on death row, Kemmler was "not a gibbering idiot, nor a driveling imbecile."

Four months before his death, under Mrs. Durston's guidance, Kemmler had become religious and was baptized into the Methodist faith. The night before his execution the condemned man received the sacrament of the last supper. His spiritual advisers felt they had done everything possible for a man of Kemmler's "meager intelligence." Warden Durston joined the ministers and the prisoner. Kemmler said he felt fine and would not "flinch at the end. I am not afraid, Warden, so long as you are in charge of the job. I won't break down if you don't."

From the Hardcover edition.

"William, It Is Time"

In the predawn hours of August 6, 1890, twenty-seven men of law, science, and medicine left their lodgings at the Osborne House and quietly made their way down State Street toward Auburn Penitentiary. It was a dull and gloomy morning with a few wet clouds in the sky. The night before had not been an easy one, and the results were written on the faces of each hunched figure. As the men walked, there was little conversation. Nearing the prison, they encountered a crowd of nearly five hundred spectators. Every tree and rooftop surrounding the ivy-covered stone prison was filled with expectant faces, and young men and boys were perched atop telegraph poles, eager to catch a glimpse of the condemned man scarcely visible through the narrow window of his lighted cell. Western Union had opened a temporary office across from the penitentiary in the dimly lit freight room of the New York Central railroad station. Inside, newspapermen and telegraph operators anxiously waited to dispatch word around the world that the first execution by electricity had taken place.

Although a ticket of admission had been issued to each witness, the men had difficulty gaining entrance to the prison. The crowd was reluctant to give way and security was tight. Warden Charles Durston had ordered the gatekeeper not to let anyone in without a ticket; one witness who had forgotten his was forced to return to the hotel to fetch it. Even the morning shift of guards was not permitted to enter the prison until the bells rang, signifying a completed execution. District Attorney George Quinby, who had prosecuted the condemned man, looked pale as he walked through the prison gate below the statue of the Continental soldier standing guard on its roof. Though he had convicted many murderers, he had never witnessed an execution.

Once inside, the men were escorted into Warden Durston's office where prisoners in white caps and aprons served them coffee and sandwiches. Warden Durston did not join his distinguished guests for breakfast. He had gone directly from his prison lodgings to the basement cell of William Kemmler, the condemned man. After an exchange of pleasantries, Warden Durston drew an official, impressive-looking document from his breast pocket, for the law required that the death warrant be read prior to execution. For his part, Kemmler remained outwardly calm. "William, it is time," said the warden. "I am ready, Mr. Durston," the condemned man responded. Then the warden, his voice trembling, read the death warrant. It differed from all previous warrants only in the prescribed method of execution. William Kemmler was to receive a current of electricity sufficient to cause death.

Kemmler listened in resolute silence. When Warden Durston finished, the condemned man replied: "All right, I am ready." The two men then sat on Kemmler's iron bunk and spoke for a few moments before Durston returned to his office on the second floor. In the entranceway he met the witnesses, now standing about, waiting. They exchanged polite nods, nothing more. The atmosphere was decidedly funereal, although the condemned man was not yet dead.

During the previous afternoon, Warden Durston had shown the witnesses the newly constructed death chamber, where electricians were putting the finishing touches on the execution apparatus. Dr. George E. Fell, a Buffalo professor who had played an important role in the chair's final design, volunteered to be strapped into it for purpose of demonstration. As he did so, Warden Durston declared his utmost confidence in the reliability of the chair. Not everyone shared this optimistic assessment: specifically, some experts had doubts about the strength and dependability of the first-ever electric chair, but ultimately, they decided it was too late to make changes. The chair, they claimed, was indeed the perfect example of science employed for the betterment of humanity-death would be quick and painless.

From the time of his arrest for the murder of his paramour, Matilda "Tillie" Ziegler, on March 29, 1889, until four days after he was sentenced to death, Kemmler remained in the Erie County jail at Buffalo. Then, in accordance with the law, he was transferred to Auburn State Prison. During the trip, Kemmler told his keepers that years before an elderly fortune-teller in Philadelphia had foretold his execution, and everything had transpired exactly as she had predicted. Five days later, on the night of May 23, Kemmler was placed in solitary confinement. He was allowed no visitors except his keepers, his lawyers, his religious advisers, and a few friends of the warden.

About three months prior to his execution, Kemmler dictated his last will and testament to the head turnkey, guard James Warner. The men were interrupted several times by the sound of hammering from two convicts working nearby on the plain pine box that would serve as Kemmler's coffin. Electrician Edwin F. Davis, who would continue as an executioner for the next twenty-four years-throwing the switch on 240 condemned men-could be heard installing the execution apparatus in the room adjacent to Kemmler's cell. Seemingly indifferent to his impending execution, Kemmler assigned his meager belongings with great care. He designated that his principal keeper, Daniel McNaughton, should receive a pictorial Bible that had provided great solace to Kemmler. To the Reverend Dr. W. E. Houghton he left a pig-in-the-clover puzzle. He gave a slate with his autograph to prison chaplain Horatio Yates. To keeper William Wemple he left a small Bible. To Mrs. Durston, the warden's wife, Kemmler gave fifty autographed cards. While in confinement, Kemmler had learned to write his name. He was very proud of this accomplishment, and presumably wanted to share it with the woman who had taught him. He also believed that after his death, the cards would be of significant monetary value.

Kemmler distrusted reporters and had always refused to answer their questions. But he was talkative with visitors, and at times quite entertaining. "He sings, cracks jokes, and . . . tells stories-the sort of stories that wouldn't look well in print," reported the Buffalo Evening News. The paper stated blithely that there was a second reason the ax murderer should be executed: "He is a bad rhymester."

While in jail Kemmler composed several drinking songs, such as this one, published in the Buffalo Evening News.

I used to live in Buffalo,

The people knew me well,

I used to go a-peddling,

A plenty did I sell.

My old clothes were ragged and torn,

My shoes wouldn't cover my toes.

My old hat went flippity flap

With a schuper to my nose.

I can't sing sing,

I won't sing sing,

I'll tell you the reason why.

I can't sing sing,

I won't sing sing,

For my whistle is getting dry.

Despite the condemned man's penchant for ribaldry, Sheriff Oliver A. Jenkins reported that Kemmler was a model prisoner. Head turnkey Warner credited Kemmler with "bearing up wonderfully well" under the constant strain of imminent death.

When he arrived at Auburn on May 24, 1889, Kemmler was an habitual cigar smoker in poor physical condition, and of a "morose" and "taciturn" disposition. While at Auburn, however, Kemmler's personal health and appearance improved greatly. He attributed this change to his enforced temperance and claimed that while in the Erie County jail awaiting trial, the guards had constantly given him tobacco and whiskey. In the months prior to his execution, he was neatly dressed and his collar was turned up in accordance with the latest fashion. His whiskers were trimmed and parted at the chin in the English style, and he always wore a black tie. During his long confinement, Kemmler's health remained good, except for a brief bout with dysentery. He passed his time by singing banjo songs with fellow death row inmate Frank Fish, and listening to his keeper read Victor Hugo's Les Misèrables.

During Kemmler's long wait on death row, the warden's wife took a special interest in him. Mrs. Durston spent considerable time with Kemmler, singing, reading Scripture, or praying with him. By the end, Kemmler appeared a better man thanks to her intervention. Under her guidance he had learned to read, and seemed to have made peace with his Maker. In a way, all the loving attention devoted to him was compensation for being the first victim of a deadly scientific experiment. The last time she spoke with Kemmler, Mrs. Durston told him he was going to a better place. She took his hand and said, "God be with you, be brave, be strong; everything will come out right."

Mrs. Durston left town for New York City the next morning. Upon her arrival, a friend met her at the railroad station and took her to a country home in Lawrence, on Long Island. Her long association with Kemmler and her genuine concern for his well-being made it too difficult for her to remain in Auburn during the execution. The citizens of Auburn, kept in the dark as to the exact date of Kemmler's execution, naturally took Mrs. Durston's departure as a sign that the fatal day was at hand.

There remained only one possible source of delay. Some observers speculated that the electrical manufacturing giant George Westinghouse might, at the last minute, get an injunction to prevent the use of Westinghouse dynamos in the execution. Attorneys for the Westinghouse Company had fought Kemmler's execution on constitutional grounds right

up to the New York Supreme Court, but since the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear its appeal, there seemed little chance that an injunction would be granted. Although the Westinghouse attorneys had argued that electrocution was cruel and unusual punishment, their real concern was the inevitable association the public would make between death by electricity and its energy source, the alternating current produced by Westinghouse dynamos (generators).

To this end, Westinghouse's attorneys filed a writ for the return of the company dynamos. The writ of replevin claimed that Harold Brown, the electrician who prepared the execution apparatus, fraudulently obtained the dynamos. Westinghouse attorneys argued unsuccessfully that Westinghouse retained an interest in its dynamos even after they were sold, giving them control over any potential misuse.

Initially, Kemmler was sentenced to die during the week of June 24, 1889. To allow his attorneys time to pursue appeals, Kemmler was twice granted a stay of execution. Finally, on July 11, 1890, his legal means of recourse exhausted, William Kemmler arrived in a Buffalo courtroom to hear the sentence of death pronounced for the third time. Accompanied by his keeper, Daniel McNaughton, Kemmler was dressed in an impeccably pressed gray suit and a black derby hat. While confined at Auburn, his dark brown beard and mustache had grown thicker. During his trial, he looked listless and confused. On this day, he was alert, yet he appeared unconcerned. Judge Henry Childs of the New York Supreme Court asked the assistant district attorney if he had any business before the court.

"If the court please," he said, "we desire to move sentence on William Kemmler."

Kemmler was asked to stand up, and Judge Childs informed him that all attempts to save his life had failed. "Yes, sir," Kemmler replied. "Have you anything to say, why a time should not be fixed for carrying out the sentence previously passed upon you?" the judge asked. After a long pause, Kemmler responded, "No, sir." The judge said he hoped the prolonged delay had given Kemmler time to think about the enormity of his crime and the justice of his conviction. He then said that the sentence would be carried out during the week of August 4, 1890. The judge concluded with the time-honored phrase, "May God have mercy upon you."

Upon his return to Auburn prison, Kemmler appeared to be in good spirits, even though he had less than two weeks to live. He no longer spent as much time with his Bible, but preferred to have novels read to him by keeper McNaughton. Kemmler often made the cryptic remark that he "would never die by electricity"; apparently he still hoped for a last-minute reprieve. Along with fellow death row inmate and convicted murderer Frank Fish, who occupied the cell adjacent to Kemmler's, he joined in the daily activities with the "utmost relish." Like Kemmler, Fish was also confident that he would not die in the electric chair. Fish seemed to be in extraordinarily good spirits, even though, at best, a reprieve from the governor would still mean that he would spend the rest of his life in prison.

Until this point, it looked as if Joseph Chapleau, a poor French-Canadian farmer who had beaten his neighbor to death with a billet of wood, would be the first to go. However, on July 16, 1890, just four days before his scheduled execution, Governor David B. Hill commuted Chapleau's death sentence to life imprisonment. The electric chair had been installed at Dannemora Prison, the place of Chapleau's confinement and scheduled execution. Now it would have to be dismantled and moved to Auburn. William Francis Kemmler would go first.

The news that Kemmler would be first came as a shock to prison officials at Auburn. It was generally known that Warden Durston did not want to preside over the first electrical execution and would avoid it if possible. Durston had hoped to benefit from the experience gained at Dannemora, and he did not want to conduct what many regarded as a risky scientific experiment.Indeed, when Durston traveled to New York City four days before the execution, most people believed he went to persuade Governor David B. Hill that Kemmler had gone insane, requiring postponement of the execution. When Durston returned to Auburn, he remained in his office, refusing to talk with anyone.

The impending execution of William Kemmler was the major topic of conversation among the citizens of Auburn. The town was full of rumors concerning Kemmler's fate, the most significant being that Kemmler had lost his mind. If this were true, it would entitle him to a stay of execution and a commutation of his sentence to life imprisonment. However, the general impression was that Kemmler's lawyers had invented the ruse to save him from the executioner's current. According to his keepers, Kemmler's physical and mental condition was about what it had been on the day he was arrested for the murder of Tillie Ziegler. Jailer McNaughton, annoyed by the persistent rumors, remarked that despite his year on death row, Kemmler was "not a gibbering idiot, nor a driveling imbecile."

Four months before his death, under Mrs. Durston's guidance, Kemmler had become religious and was baptized into the Methodist faith. The night before his execution the condemned man received the sacrament of the last supper. His spiritual advisers felt they had done everything possible for a man of Kemmler's "meager intelligence." Warden Durston joined the ministers and the prisoner. Kemmler said he felt fine and would not "flinch at the end. I am not afraid, Warden, so long as you are in charge of the job. I won't break down if you don't."

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Fascinating and provocative. . . . Moran skillfully used the story of the creation of the electric chair to illustrate the brutal clash between Edison and Westinghouse.” —Washington Post Book World

“Fascinating. . . . Moran conclusively shows that Edison hoped to discredit alternating current--by associating it in the public mind with death--and advance his own direct current." —Los Angeles Times

"Chilling. . . . A 'Coke-versus-Pepsi' story as if told by Stephen King. . . . A macabre jolt of history." —Chicago Sun-Times

“A remarkable account. . . . A fantastic tale, well told.” —Forbes

“[An] engaging analysis of the relationship between electrocution and the personal and corporate battles waged between Edison and Westinghouse.” —Louis P. Masur, Chicago Tribune

“Richard Moran shows us not only how the death penalty in America affects condemned prisoners, but also how it is used by powerful interests in our society to further their own political and economic ends. . . . Five stars, and three cheers, for Professor Moran!” —Sister Helen Prejean, author of Dead Man Walking

“Riveting. . . . Moran [has a] lively reportorial style. . . . In this narrative of callous ambition and hypocrisy, a condemned criminal plays an unexpectedly dignified role.” —Seattle Weekly

"Compelling. . . . Reads like pages torn from today's headlines about nefarious CEOs and corporate greed." —Albany Times Union

“Haunting…. Incisive… A chilling look at something that has become a too-common theme of modern times: the use of technology to develop new ways of killing.” —Roanoke Times

“An eye-opening and riveting account of the battle for the future of electricity and the part that played in changing the technology of execution.” —Wilmington Sunday News Journal

“Fascinating. . . . Moran conclusively shows that Edison hoped to discredit alternating current--by associating it in the public mind with death--and advance his own direct current." —Los Angeles Times

"Chilling. . . . A 'Coke-versus-Pepsi' story as if told by Stephen King. . . . A macabre jolt of history." —Chicago Sun-Times

“A remarkable account. . . . A fantastic tale, well told.” —Forbes

“[An] engaging analysis of the relationship between electrocution and the personal and corporate battles waged between Edison and Westinghouse.” —Louis P. Masur, Chicago Tribune

“Richard Moran shows us not only how the death penalty in America affects condemned prisoners, but also how it is used by powerful interests in our society to further their own political and economic ends. . . . Five stars, and three cheers, for Professor Moran!” —Sister Helen Prejean, author of Dead Man Walking

“Riveting. . . . Moran [has a] lively reportorial style. . . . In this narrative of callous ambition and hypocrisy, a condemned criminal plays an unexpectedly dignified role.” —Seattle Weekly

"Compelling. . . . Reads like pages torn from today's headlines about nefarious CEOs and corporate greed." —Albany Times Union

“Haunting…. Incisive… A chilling look at something that has become a too-common theme of modern times: the use of technology to develop new ways of killing.” —Roanoke Times

“An eye-opening and riveting account of the battle for the future of electricity and the part that played in changing the technology of execution.” —Wilmington Sunday News Journal