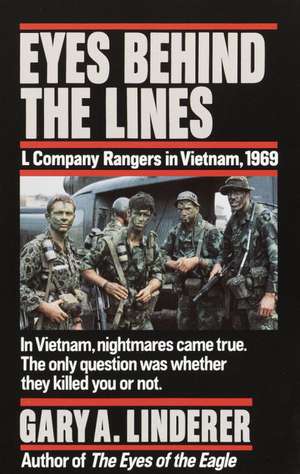

Eyes Behind the Lines: L Company Rangers in Vietnam, 1969

Autor Gary A. Lindereren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 1991

Preț: 57.37 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 86

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.98€ • 11.49$ • 9.08£

10.98€ • 11.49$ • 9.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780804108195

ISBN-10: 0804108196

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 108 x 176 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

ISBN-10: 0804108196

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 108 x 176 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.15 kg

Editura: Presidio Press

Extras

Eyes Behind the Lines Prologue

I had to smile at the irony of it all as the C-130 slammed onto the runway at the Phu Bai airstrip near the imperial city of Hue. Only seven months ago, another C-130 had delivered me to this same hot, sticky, strip of tarmac situated on the coastal plain in the northern part of the Republic of Vietnam. Back then, I had been a green twenty-one-year-old, sold on the idea that I was one of American’s finest, answering my country’s call. I was full of piss and vinegar and ready to take on Uncle Ho and his whole Asian horde. I had volunteered for airborne infantry, advanced individual training, and Jump School in an attempt to get into Officer Candidate School; my two years of college and ROTC had not impressed the army enough to select me as a candidate for the program. However, it did impress them enough to send me halfway around the world to attend a one-year seminar in combat survival.

I had been lucky enough to be assigned to the famous “Screaming Eagles” of the 101st Airborne Division and had opted for “fraternity life” by volunteering for special operations duty with F Company, 58th Infantry (Long Range Patrol).

The army had done an excellent job of pumping all of us full of massive doses of self-confidence. Back in the States at Fort Gordon and Fort Benning, the care had hot-wired my buddies and me into believing that we were indeed “the baddest motherfuckers in the valley.” We developed a heightened sense of immortality and esprit that caused many of us to say a prayer each night that the war would go on long enough for us to get over there.

Some of our instructors threatened us with stories about how tough “Charlie” was and warned us that he would blow us away in a minute if he caught us “half stepping’. ” They promised that if we fell asleep on guard, we}d wake up wearing an extra smile—one cut from ear to ear. After all, we were Airborne, and the baddest motherfuckers in the valley. Airborne didn’t half step, and we sure as hell didn’t sleep on guard. Mr. Charles had better watch his ass when we got to the Nam.

My first seven months in country had exposed the lie. The cadre hadn’t been bullshitting us, and we weren’t the baddest motherfuckers in the valley, either. The damn valley was full of bad motherfuckers. Upon our arrival, we quickly discovered that we were as green as the stiff, chafing new jungle fatigues they issued us. The months of training back in the States had been woefully inadequate for what we would experience in the Nam.

The first few weeks proved to be a twenty-four-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week cram course, “How to Stay Alive in a Hostile Environment.” And no training, in any amount, could truly have prepared us for the actual trials and tribulations of combat. Combat was its own finishing school. But we learned! Slowly but surely, we became jungle-hardened LRPs.

We developed the ability to perform under adverse conditions and in situations that would have destroyed lesser men. Those who couldn’t cut it were quickly and quietly weeded out of the program and sent to other units. There was no place in the Long Range Patrol for the weak, the timid, the unmotivated. In time, our “greenness” had faded, just as the color had bleached from our uniforms and the rest of our gear. The dense, mountainous jungles and the constant sun/heat, sun/rain, sun/sweat, sun/dust cycle that was Vietnam had leached the parade-ground perfection out of each of us.

Humping the steep mountains of the Annamese Cordilla with hundred-pound rucksacks had increased our endurance. We learned to stalk the thick vegetation flanking the enemy’s high-speed trails with the stealth of a panther. We learned how to wait for the enemy along those trails, and to strike with the speed and deadliness of the cobra. We made an alliance with the jungle. It soon became our friend, providing us with shelter and cover as we sought out our enemies. We conquered our fear of the darkness, and learned how to use it to conceal us from the searching eyes of the NVA. We had studied the enemy at his own game. After a while, we had become its master.

For years, our six-man teams had infiltrated silently into the enemy’s staging areas to gather intelligence and to find him and kill him where he thought he was secure. Swift but deadly ambushes had left numerous NVA patrols no more than fly-blown heaps of carrion along the jungle trails. Many NVA couriers and VC political officers had died while moving between the lowland villages and the distant mountain sanctuaries. Ammo caches had exploded in the faces of unsuspecting NVA soldiers attempting to resupply themselves. Base camps and supply depots had been destroyed by sudden artillery barrages and well-plotted B-42 “Arc Light” bombing runs. Numerous troop concentrations had been destroyed in sudden assaults by Cobra gunships or airstrikes by fast-flying U.S. fighter-bombers.

The NVA knew that this death and destruction was not the result of mere chance. Someone was out there watching them! The enemy had come to fear and hate, yet respect, the “men with the painted faces.” We had adopted their style of war. They had always preferred to pick the time and place to engage their enemies in combat. The men of the Long Range Patrols had taken that option away from them. They were being taught the same demoralizing lesson that they had forced our soldiers to learn: death was everywhere in Vietnam. There were no havens!

A couple of weeks before I reached the “hump,” the midpoint in my twelve-month tour, the NVA took back their option. It was my fourteenth mission, a twelve-man “heavy” team recon patrol into the Roung-Roung Valley.

Sgt. Al Contreros was the overall team leader of the two combined teams. We had inserted at dusk into an elephant grass-choked ravine next to some heavy jungle. John Sours had broken his ankles on the insertion. Not wanting to compromise the team, he had played down the extent of his injury.

We moved into the jungle at dusk and located a wide, well-used high-speed trail snaking along the base of a ridgeline. We followed it east until we heard a warning shot a couple hundred meters to our front. We set up an L-shaped ambush at a bend in the road and lay back to await the dawn.

During the night enemy patrols with flashlights came looking for us. They passed within ten feet of our positions. We held our fire, not wanting to initiate the ambush with so many alerted NVA soldiers in the immediate vicinity.

At dawn, we discovered that Sours’ ankles were too swollen for him to function without help. The team leader made the decision to extract him from our original LZ and sent him down the ravine with an escort of two other LRPs. As the medevac ship lifted him out, we heard another shot up the trail from our ambush site. The sound of the helicopter extracting Sours must have made the NVA think that we had all been pulled out. The second shot was probably and “All clear” signal to the NVA soldiers in the area.

An hour later, ten NVA entered our kill zone and we initiated the ambush, killing nine of them. Their point man, although wounded, escaped. We checked the bodies and discovered that among the dead were four nurses and an NVA major with a dispatch case full of maps and documents. We called for a reaction force to come in and help us secure the area. We waited an hour before being informed that no reaction force was available. In addition, our helicopters were tied up in a brigade-size combat assault and would be unable to extract us for several hours.

Our position was precarious. We had stayed too long at the kill zone waiting for help that would not be arriving. We had violated one of the cardinal rules of long-range patrolling—never remain at an ambush site without being reinforced. The team leader informed us that we were to move out immediately and attempt to find a more defensive position on higher ground.

Jim Venable, our assistant team leader, walked out into a nearby clearing to flash our position to our company commander’s circling command—and-control chopper. As he sighted through the hole of the signal mirror, NVA soldiers hidden in the surrounding jungle opened up on him with automatic weapon, severely wounding him in the arm, neck, and chest. The rest of the team laid down a heavy volume of fire as two other LRPs ran out and dragged the wounded point man back into the perimeter.

Thirty or forty NVA assaulted our position from the direction of the original LZ. We beat them back, killing several of them in the process. The next few hours were hell. We drove one assault after another away from our position, directing artillery and Cobra gunships against the surrounding NVA. Our ammunition was running low, when the team leader ordered us to tighten up the perimeter so that he could direct our supporting fire in closer to us. As the remainder of the team moved to consolidate their positions, a large, command-detonated claymore mine exploded to our rear, sending thousands of deadly pellets through our ranks. When the smoke cleared, four LRPs were dead, and the remainder were wounded. Only three of us were still able to defend our perimeter.

For two hours we fought desperately to stay alive. Cobra gunships crisscrossed our perimeter in a determined effort to keep the NVA from wiping out the survivors. We brought in three medevac choppers and were able to get three of the most seriously wounded out by jungle penetrator.

Just as we were about to write ourselves off, a hastily formed reaction force comprised of LRPs from our own company helicopter-assaulted into a bomb-crater a hundred meters from our position and fought its way through the surrounding NVA to our perimeter. We were saved. Laterm in the surgical center in Phu Bai, I was to find out how serious our losses had been. Sgt. Al Contreros, the team leader, Sgt. Mike Reiff, Sp4c. Art Heringhausen, and my best friend, Sp4c. Terry Clifton, had been killed. Sp4c. Frank Souza, Sp4c. Riley Cox, Sp4c. Jim Bacon, Sgt. Jim Venable, and Sp4c. Steve Czepurny had all been wounded so seriously that they were being shipped back to the States. Their tours were over. Only Sgt. John Sours, Sp4c. Billy Walkabout, and myself would return to duty after recovering from our wounds.

It was a heavy loss for F Company, one that would take months to recover from. I had lost a best friend on that hilltop, a loss that would cause me grief and anguish for years to follow. You see, it had been my fault that he was there that day.

I had witnessed another man’s heroism that should have won him the Medal of Honor. On three separate occasions, Billy Walkabout, although wounded in the hands, had charged unarmed up to the NVA positions to retrieve an errantly dropped jungle penetrator to medevac our wounded. I had learned of my own vulnerability. Death had been at my side that day. I had accepted it. I had made peace with my maker and then, in the next instant, had begged Him to spare me. I had even made up my mind to kill the wounded and then myself, if it appeared that we would be overrun. I would not let myself or my buddies be taken prisoner. Was I heroic, self-serving, or playing God? Therese were questions I could never answer.

After four weeks of convalescence at the 6th convalescent center at Cam Ranh Bay, I had conned my doctor into sending me back to my unit early. I could not bear to goldbrick in the security of a convalescent center while my comrades were still pulling missions up in I Corps. REMF (rear-echelon motherfucker) life was not for me! They cut orders shipping me back to Bien Hoa to clear the division rear before being reassigned. There was a good chance I would be sent to another unit.

I spent a couple of days with an air force buddy from my home town at the air base at Cam Ranh Bay, then hopped a C-130 directly to Phu Bai. I decided not to report to Bien Hoa and take the chance of being shipped to another outfit. I would be good to get back. My first Christmas away from my family and fiancée would not be spent with a bunch of strangers.

I had to smile at the irony of it all as the C-130 slammed onto the runway at the Phu Bai airstrip near the imperial city of Hue. Only seven months ago, another C-130 had delivered me to this same hot, sticky, strip of tarmac situated on the coastal plain in the northern part of the Republic of Vietnam. Back then, I had been a green twenty-one-year-old, sold on the idea that I was one of American’s finest, answering my country’s call. I was full of piss and vinegar and ready to take on Uncle Ho and his whole Asian horde. I had volunteered for airborne infantry, advanced individual training, and Jump School in an attempt to get into Officer Candidate School; my two years of college and ROTC had not impressed the army enough to select me as a candidate for the program. However, it did impress them enough to send me halfway around the world to attend a one-year seminar in combat survival.

I had been lucky enough to be assigned to the famous “Screaming Eagles” of the 101st Airborne Division and had opted for “fraternity life” by volunteering for special operations duty with F Company, 58th Infantry (Long Range Patrol).

The army had done an excellent job of pumping all of us full of massive doses of self-confidence. Back in the States at Fort Gordon and Fort Benning, the care had hot-wired my buddies and me into believing that we were indeed “the baddest motherfuckers in the valley.” We developed a heightened sense of immortality and esprit that caused many of us to say a prayer each night that the war would go on long enough for us to get over there.

Some of our instructors threatened us with stories about how tough “Charlie” was and warned us that he would blow us away in a minute if he caught us “half stepping’. ” They promised that if we fell asleep on guard, we}d wake up wearing an extra smile—one cut from ear to ear. After all, we were Airborne, and the baddest motherfuckers in the valley. Airborne didn’t half step, and we sure as hell didn’t sleep on guard. Mr. Charles had better watch his ass when we got to the Nam.

My first seven months in country had exposed the lie. The cadre hadn’t been bullshitting us, and we weren’t the baddest motherfuckers in the valley, either. The damn valley was full of bad motherfuckers. Upon our arrival, we quickly discovered that we were as green as the stiff, chafing new jungle fatigues they issued us. The months of training back in the States had been woefully inadequate for what we would experience in the Nam.

The first few weeks proved to be a twenty-four-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week cram course, “How to Stay Alive in a Hostile Environment.” And no training, in any amount, could truly have prepared us for the actual trials and tribulations of combat. Combat was its own finishing school. But we learned! Slowly but surely, we became jungle-hardened LRPs.

We developed the ability to perform under adverse conditions and in situations that would have destroyed lesser men. Those who couldn’t cut it were quickly and quietly weeded out of the program and sent to other units. There was no place in the Long Range Patrol for the weak, the timid, the unmotivated. In time, our “greenness” had faded, just as the color had bleached from our uniforms and the rest of our gear. The dense, mountainous jungles and the constant sun/heat, sun/rain, sun/sweat, sun/dust cycle that was Vietnam had leached the parade-ground perfection out of each of us.

Humping the steep mountains of the Annamese Cordilla with hundred-pound rucksacks had increased our endurance. We learned to stalk the thick vegetation flanking the enemy’s high-speed trails with the stealth of a panther. We learned how to wait for the enemy along those trails, and to strike with the speed and deadliness of the cobra. We made an alliance with the jungle. It soon became our friend, providing us with shelter and cover as we sought out our enemies. We conquered our fear of the darkness, and learned how to use it to conceal us from the searching eyes of the NVA. We had studied the enemy at his own game. After a while, we had become its master.

For years, our six-man teams had infiltrated silently into the enemy’s staging areas to gather intelligence and to find him and kill him where he thought he was secure. Swift but deadly ambushes had left numerous NVA patrols no more than fly-blown heaps of carrion along the jungle trails. Many NVA couriers and VC political officers had died while moving between the lowland villages and the distant mountain sanctuaries. Ammo caches had exploded in the faces of unsuspecting NVA soldiers attempting to resupply themselves. Base camps and supply depots had been destroyed by sudden artillery barrages and well-plotted B-42 “Arc Light” bombing runs. Numerous troop concentrations had been destroyed in sudden assaults by Cobra gunships or airstrikes by fast-flying U.S. fighter-bombers.

The NVA knew that this death and destruction was not the result of mere chance. Someone was out there watching them! The enemy had come to fear and hate, yet respect, the “men with the painted faces.” We had adopted their style of war. They had always preferred to pick the time and place to engage their enemies in combat. The men of the Long Range Patrols had taken that option away from them. They were being taught the same demoralizing lesson that they had forced our soldiers to learn: death was everywhere in Vietnam. There were no havens!

A couple of weeks before I reached the “hump,” the midpoint in my twelve-month tour, the NVA took back their option. It was my fourteenth mission, a twelve-man “heavy” team recon patrol into the Roung-Roung Valley.

Sgt. Al Contreros was the overall team leader of the two combined teams. We had inserted at dusk into an elephant grass-choked ravine next to some heavy jungle. John Sours had broken his ankles on the insertion. Not wanting to compromise the team, he had played down the extent of his injury.

We moved into the jungle at dusk and located a wide, well-used high-speed trail snaking along the base of a ridgeline. We followed it east until we heard a warning shot a couple hundred meters to our front. We set up an L-shaped ambush at a bend in the road and lay back to await the dawn.

During the night enemy patrols with flashlights came looking for us. They passed within ten feet of our positions. We held our fire, not wanting to initiate the ambush with so many alerted NVA soldiers in the immediate vicinity.

At dawn, we discovered that Sours’ ankles were too swollen for him to function without help. The team leader made the decision to extract him from our original LZ and sent him down the ravine with an escort of two other LRPs. As the medevac ship lifted him out, we heard another shot up the trail from our ambush site. The sound of the helicopter extracting Sours must have made the NVA think that we had all been pulled out. The second shot was probably and “All clear” signal to the NVA soldiers in the area.

An hour later, ten NVA entered our kill zone and we initiated the ambush, killing nine of them. Their point man, although wounded, escaped. We checked the bodies and discovered that among the dead were four nurses and an NVA major with a dispatch case full of maps and documents. We called for a reaction force to come in and help us secure the area. We waited an hour before being informed that no reaction force was available. In addition, our helicopters were tied up in a brigade-size combat assault and would be unable to extract us for several hours.

Our position was precarious. We had stayed too long at the kill zone waiting for help that would not be arriving. We had violated one of the cardinal rules of long-range patrolling—never remain at an ambush site without being reinforced. The team leader informed us that we were to move out immediately and attempt to find a more defensive position on higher ground.

Jim Venable, our assistant team leader, walked out into a nearby clearing to flash our position to our company commander’s circling command—and-control chopper. As he sighted through the hole of the signal mirror, NVA soldiers hidden in the surrounding jungle opened up on him with automatic weapon, severely wounding him in the arm, neck, and chest. The rest of the team laid down a heavy volume of fire as two other LRPs ran out and dragged the wounded point man back into the perimeter.

Thirty or forty NVA assaulted our position from the direction of the original LZ. We beat them back, killing several of them in the process. The next few hours were hell. We drove one assault after another away from our position, directing artillery and Cobra gunships against the surrounding NVA. Our ammunition was running low, when the team leader ordered us to tighten up the perimeter so that he could direct our supporting fire in closer to us. As the remainder of the team moved to consolidate their positions, a large, command-detonated claymore mine exploded to our rear, sending thousands of deadly pellets through our ranks. When the smoke cleared, four LRPs were dead, and the remainder were wounded. Only three of us were still able to defend our perimeter.

For two hours we fought desperately to stay alive. Cobra gunships crisscrossed our perimeter in a determined effort to keep the NVA from wiping out the survivors. We brought in three medevac choppers and were able to get three of the most seriously wounded out by jungle penetrator.

Just as we were about to write ourselves off, a hastily formed reaction force comprised of LRPs from our own company helicopter-assaulted into a bomb-crater a hundred meters from our position and fought its way through the surrounding NVA to our perimeter. We were saved. Laterm in the surgical center in Phu Bai, I was to find out how serious our losses had been. Sgt. Al Contreros, the team leader, Sgt. Mike Reiff, Sp4c. Art Heringhausen, and my best friend, Sp4c. Terry Clifton, had been killed. Sp4c. Frank Souza, Sp4c. Riley Cox, Sp4c. Jim Bacon, Sgt. Jim Venable, and Sp4c. Steve Czepurny had all been wounded so seriously that they were being shipped back to the States. Their tours were over. Only Sgt. John Sours, Sp4c. Billy Walkabout, and myself would return to duty after recovering from our wounds.

It was a heavy loss for F Company, one that would take months to recover from. I had lost a best friend on that hilltop, a loss that would cause me grief and anguish for years to follow. You see, it had been my fault that he was there that day.

I had witnessed another man’s heroism that should have won him the Medal of Honor. On three separate occasions, Billy Walkabout, although wounded in the hands, had charged unarmed up to the NVA positions to retrieve an errantly dropped jungle penetrator to medevac our wounded. I had learned of my own vulnerability. Death had been at my side that day. I had accepted it. I had made peace with my maker and then, in the next instant, had begged Him to spare me. I had even made up my mind to kill the wounded and then myself, if it appeared that we would be overrun. I would not let myself or my buddies be taken prisoner. Was I heroic, self-serving, or playing God? Therese were questions I could never answer.

After four weeks of convalescence at the 6th convalescent center at Cam Ranh Bay, I had conned my doctor into sending me back to my unit early. I could not bear to goldbrick in the security of a convalescent center while my comrades were still pulling missions up in I Corps. REMF (rear-echelon motherfucker) life was not for me! They cut orders shipping me back to Bien Hoa to clear the division rear before being reassigned. There was a good chance I would be sent to another unit.

I spent a couple of days with an air force buddy from my home town at the air base at Cam Ranh Bay, then hopped a C-130 directly to Phu Bai. I decided not to report to Bien Hoa and take the chance of being shipped to another outfit. I would be good to get back. My first Christmas away from my family and fiancée would not be spent with a bunch of strangers.

Descriere

The job of the all-volunteer Rangers was to find the enemy, observe him, or kill him--all the while behind enemy lines, where discovery could mean a quick, violent death. Whether ambushing NVA soldiers or rescuing downed air crews, the Rangers demanded--and got--extraordinary performance from their troops. Sequel to The Eyes of the Eagle.