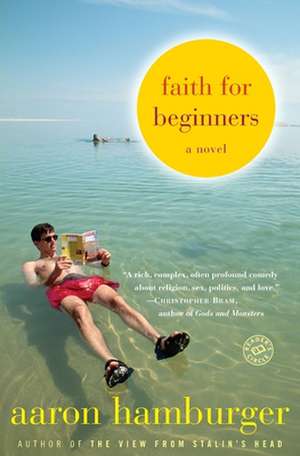

Faith for Beginners

Autor Aaron Hamburgeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2006

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Lambda Literary Awards (2005)

In the summer of 2000, Israel teeters between total war and total peace. Similarly on edge, Helen Michaelson, a respectable suburban housewife from Michigan, has brought her ailing husband and rebellious college-age son, Jeremy, to Jerusalem. She hopes the journey will inspire Jeremy to reconnect with his faith and find meaning in his life . . . or at least get rid of his nose ring.

It’s not that Helen is concerned about Jeremy’s sexual orientation (after all, her other son is gay as well). It’s merely the matter of the overdose (“Just like Liza!” Jeremy had told her), the green hair, and what looks like a safety pin stuck through his face. After therapy, unconditional love, and tough love . . . why not try Israel?

Yet in seductive and dangerous surroundings, with the rumbling of violence and change in the air, in a part of the world where “there are no modern times,” mother and son become new, old, and surprising versions of themselves.

Funny, erotic, searingly insightful, and profoundly moving, Faith for Beginners is a stunning debut novel from a vibrant new voice in fiction.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 108.09 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 162

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.69€ • 21.34$ • 17.51£

20.69€ • 21.34$ • 17.51£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 12-26 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812973204

ISBN-10: 0812973208

Pagini: 353

Dimensiuni: 135 x 201 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812973208

Pagini: 353

Dimensiuni: 135 x 201 x 21 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

Aaron Hamburger is the author of the short-story collection The View from Stalin’s Head, for which he was awarded the Rome Prize by The American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was awarded a fellowship from the Edward F. Albee Foundation and won first prize in the David Dornstein Memorial Creative Writing Contest for Young Adult Writers. His writing has appeared in The Village Voice, Out, Nerve, and Time Out New York. He teaches writing at Columbia University and lives in New York City.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

A LIST OF PLANTS THAT GROW OUT OF THE WAILING WALL

1.HENBANE, or “SHIKARON” (“intoxication” in Hebrew). When ingested, induces a state of deep, colorful hallucination and finally a very pleasant death. Most common plant in the Wall.

2.PODOSNOMA. Roots can crack rocks to draw out water.

3.SICILIAN SNAPDRAGON. Prefers high altitudes.

4.HORSETAIL KNOTGRASS. Antidote for snakebite and the evil eye.

5.THORNY CAPER. Makes an excellent marinade for roast chicken.

6.PHAGNALON. Small and shy.

It was an intolerably hot morning near the end of June. A mother, father, and son named Michaelson floated on a cruise ship off the coast of Haifa, along with the other 251 members of the Millennium Marathon 2000. As they approached the harbor, their ship was briefly turned back by a black military helicopter, chartered to reenact the drama of Holocaust refugees sneaking into Palestine during the British Mandate. The Michiganders offered a light round of confused applause, and as if by command, the helicopter instantly swirled away.

Sweaty, bleary-eyed, and a bit deaf from the chopping of the helicopter, the Michaelsons collected their luggage and duty-free bags and streamed down the gangplanks with the other Michiganders. Aliza, the rabbinic intern, tried unsuccessfully to lead their group in a chorus of “Jerusalem of Gold.” Her lavender song sheets fluttered down the side of the boat into the murky green water of the harbor.

On dry land, they received commemorative T-shirts with a handprint-shaped outline of their state and the message “THE Millennium Marathon 2000! What’s good for the goose is even better for the Michigander!”

“Isn’t that a riot?” said Mrs. Michaelson, fifty-eight years old and often called handsome. She held a shirt up to the chest of her bored-looking son, who clearly did not think it was a riot. Her husband, busy emptying his nose into a hankie, had no opinion. And to tell the truth, Mrs. Michaelson herself didn’t think it was a riot either. She was distracted by the heat as well as the realization that this was the first time she had ever set foot in Asia.

Before she could explore the continent further, their group was confronted by three air-conditioned buses, two unlicensed Russian photographers, who were chased away by the police, and one rabbi. His name was Rabbi Sherman, but he encouraged them to call him Rabbi Rick. He looked younger than Mrs. Michaelson had expected—though actually in his forties, he could have passed for thirty-five—and more attractive than any rabbi had a right to be. He was also unusually hairy. The top of his head, his arms, his hands, the back of his neck, and even his feet, peeking through the gaps in his brown leather sandals, were all covered in black wool.

Rabbi Sherman, riding in the first bus of their caravan, led them to their hotel, which boasted a commanding view of the harbor. Mrs. Michaelson took it in alone on the terrace after dinner. A sultry breeze blew in from the purple water of Haifa harbor, where the crescent moon was reflected as a series of white dashes on the waves. Within minutes, her dress was sticking to the skin under her arms and along the neckline.

Clutching an empty wineglass, Mrs. Michaelson closed her eyes and imagined she was having a religious moment. A trickle of sweat inched its way down between her breasts; a mosquito tickled her ear. “It’s so late. . . .” she murmured.

A high, sharp voice, like a seagull, cried out, “Who’s there?”

Someone moved in the shadows. Mrs. Michaelson made out the wide smile first, a wall of chiseled white teeth. The smile belonged to a short, sharp-chinned woman with pointy elbows jutting out of a glittery tissue-thin shawl. She padded up to Mrs. Michaelson in her bare feet.

“Sherry Sherman,” said the stranger, her right hand thrust forward like a gun.

Mrs. Michaelson, who wasn’t the type to accost strangers minding their own business, gave a bored smile, as if she were placing her order at dinner. When she smiled, her kind gray eyes pressed together so tightly it was impossible to see into them.

“I’m sort of a den mother to you folks,” Sherry said. “Rabbi Rick and I live together in Tel Aviv. No, no, nothing like that. Of course, I’m much too old for him. And there’s one more small matter: he’s my son! By the way, your dress is stunning. Did you find it in New York City? I hope you don’t mind spilling all your secrets.”

“This?” Mrs. Michaelson said, holding out the material so that Sherry Sherman could admire the workmanship more easily. “It’s just something I made. The pattern was easy.”

“You made it?” said Sherry, fluffing her tight curls with the tips of her fingers. She was bony and spry like a cat, not a bit like the tall, strapping rabbi, who plodded ahead of their group with his shoulders thrown back like the Great White Hunter. “I don’t know anyone who still sews. Maybe a button, not a whole dress. You really made it? Now that’s special. But aren’t I interrupting? I heard you talking to someone.”

“I wasn’t talking to anyone . . .” said Mrs. Michaelson, who talked to herself so often that she’d had plenty of practice making excuses.

“Hush! Do you feel that breeze? That’s a typical Middle Eastern cooling breeze blowing in off the Mediterranean. Take a moment to let it soak into your skin.”

Mrs. Michaelson took a moment, but didn’t notice anything particularly special about the breeze. Chatty women made her feel like the chubby, soft-spoken girl she’d been in grade school, always dressed in stiff, frilly dresses suitable for antique dolls.

“You’re here for an adventure. Am I right? In that case, I’ll have to keep my eye on you to see how it turns out. If only I could visit Israel for the first time all over again.” Sherry sighed, then recited, “ ‘If I forget thee, Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.’ That’s from Psalms.”

“I’ve heard that one,” Mrs. Michaelson said, smashing a mosquito on her neck.

“ ‘In Jerusalem, everyone remembers he’s forgotten something, but he doesn’t remember what it is.’ That’s by Yehuda Amichai, one of our great poets.” Sherry stared directly at Mrs. Michaelson, who looked away, back at the harbor. “You seem to have a case of the jitters, dear. It’s natural. I see it in all you first-timers, especially Americans. Listen, I’ve lived in Israel for six months, so I’m something of an expert now, and I can tell you we’re far safer here than in the States. Street crime’s practically unheard of. Death by tourism? Extremely rare.”

Mrs. Michaelson preferred not to dwell on morbid subjects like death. Someday she would die but, thankfully, when it happened, she wouldn’t be around to know about it.

“If we change how we live, then the terrorists win,” Sherry said with a firm nod. “You’re far more likely to die in a horrible car crash at home than by a bomb in an Israeli marketplace, but do you stop driving? No. You minimize the risk by wearing a seat belt, which, thanks to Ralph Nader, is now standard in all vehicles. Rabbi Rick and I have decided to vote for Nader in November, but he’d never tell you that, because my son makes it a point to stay out of American political debates. Can I ask why you’re holding that wineglass?”

“To calm my nerves” would have been the honest answer. At dinner, Mrs. Michaelson had slipped it into her purse when her son wasn’t looking, in case one of the waiters forgot her warnings and filled the glass by accident. She’d imagined the resulting scene: Jeremy grabbing the glass of wine in a fit of weakness, downing it in a single greedy gulp, and then falling to the floor, where he’d lie twitching like an epileptic.

But how to explain all that to Sherry Sherman, who said, “Oh, I see it’s a sore subject. I never pry,” and padded away.

For two weeks, their troika of air-conditioned buses trekked up and down the Holy Land, from the snows of Mount Hermon (no snow in summer) to the sandy wastes of the Negev (hot, poisonous winds, and dreary scenery).

Mrs. Michaelson applauded for an orchestra of Russian immigrants playing Gershwin at a kibbutz in the Galilee, though she didn’t really like Gershwin. Too showy.

She ate pita pounded thin and then toasted over an open fire by Bedouins in a desert camp in the Negev.

“Good?” they asked.

“Good, good!” she reassured them.

She watched Mr. Michaelson, who’d mysteriously dropped the title “Doctor” when he got sick, rape the Holy Land of its souvenirs: heart-shaped blue-glass eyes, inflatable camels, Dead Sea mud masks, a book of Golda Meir’s favorite falafel recipes, an antique Roman coin that came with a certificate of authenticity.

She received a welcome kit with a miniature cake and an airline-size bottle of kosher red wine (she confiscated Jeremy’s bottle while he was in the shower), a Millennium Marathon Daily Bulletin photocopied on goldenrod paper, and a plastic bottle of from sand to land sand, which Jeremy dumped into her glass of wine one night at dinner to prove he wasn’t the least bit tempted to steal a sip.

She pressed flesh with the mayors of Tel Aviv, Rishon Le-Tzion, and Eilat, where their hotel offered free samples of peppermint foot lotion, which she used to massage her bunions.

She witnessed a phalanx of ten women dressed all in black standing by the side of the highway near the Megiddo junction. Perfectly silent and still, the Women in Black carried signs in Hebrew, English, and Arabic calling for the end of the “occupation.”

She quickly learned the two ways to say “No thanks, I’m stuffed” in Hebrew, a matter of life and death in a country where tourists were apt to be pelted with unwanted extra helpings. The first expression meant “I’ve had enough to eat.” The other, which wasn’t particularly nice, meant “I’m so full I’m going to explode like an Arab.”

She clipped a photo of Ehud Barak from the International Herald Tribune, because he looked exactly like her father when he’d been Barak’s age. Back then, her father woke up at six a.m. to work at his grocery stand, then came home late, his hands chafed raw from washing vegetables in ice water. She loved him, but she used to hate touching his hands.

She posed for a picture beside a camel tied to a parking meter and invited Jeremy, standing a few feet away from everyone as usual with one of his cigarettes, to pose too. And, just for the picture, could he take out the safety pin he’d seen fit to stick through his nose? (There was nothing they could do about the green stripes in his hair, though by pretending to pat him on the head, she often managed to smooth out the sharp edges of his “faux Mohawk,” a pyramid of hair cemented with gel.)

It wasn’t a safety pin.

“It looks like a safety pin,” Mrs. Michaelson said. “What’s the difference?”

Jeremy pulled at the metal, stretching out his nostril. “This is sterilized. Also, for your information, camels aren’t the least bit biblical. They weren’t domesticated until six hundred years after Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.”

At times like this she saw some of her own awkwardness in him, and she couldn’t help laughing.

“Why do I open my mouth?” he said. “You never listen to me anyway.”

So Mrs. Michaelson stood alone by the unbiblical camel, blinked away the beads of perspiration dripping into her eyes, and claimed to be enjoying herself. She recalled the dignity of the Women in Black silently protesting near Megiddo and imagined that by taking the picture she, too, was staging a silent protest.

As soon as the camera flashed, several charming Bedouin boys jumped down from the olive trees and came running at them, shouting, “Money! Money!”

Mostly she sweated. Miserably. They all sweated. Everywhere the Michiganders traveled, guides and drivers and souvenir hawkers told them how unlucky they were to visit Israel during a sharav (Hebrew) or a hamsin (Arabic), a blistering heat wave. These hamsins (most Israelis preferred the Arabic word) scalded the Levant every summer, but there hadn’t been one this bad in a while.

“We didn’t have one so bad for maybe fifty years, giving or taking,” said Baruch, their Israeli driver, as they churned along Highway 1 from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. She preferred Baruch to Igor, who stank of dill. Beside her snored Mr. Michaelson, leaking threads of drool from the corners of his mouth. She was so glad to see him enjoy a good sleep, she didn’t care how he looked. Jeremy sat four rows behind them and pushed up his hair. He’d caused a sensation that morning by pinning his name tag to the zipper of his camouflage cutoffs.

“The last time we had such a hamsin, it was a few weeks after our War for Independence,” said Baruch, his shirt unbuttoned down to his navel. He was always trying to impress her by careening around the edges of sheer cliffs or aiming their bus at fruit stands in picturesque stone alleys. “I was a boy, but I still remember everywhere there was shooting and crazy men with guns in their hands.”

“Terrifying,” she said as if she cared, but she’d heard so many hamsin stories by then, they blended together. She was surprised there was no commemorative T-shirt.

“That’s only the start, my dear Shoshana.” Baruch always called her Shoshana, Hebrew for Rose, though it wasn’t her name. “In a hamsin, a man can get all turned around. Normal becomes crazy and crazy becomes normal.”

Mrs. Michaelson had dreamed of exactly that kind of transformation for her son when she’d signed them up to visit Israel. No luck so far, and now they had only five days left before they returned home. She felt ashamed when she thought of how naïvely she’d pushed them all to come, and at such expense.

Their bus grunted uphill, slouching beneath a heraldic banner across Highway 1: Peugeot welcomed them to Jerusalem, Mrs. Michaelson’s final, though perhaps best, hope. If Jeremy was going to find himself, where could be more fitting than the capital of the Jews’ home turf?

Almost fifteen years earlier, Mrs. Michaelson had transferred her two boys to Jewish Day School after an economically and educationally challenged African American boy had punched Jeremy’s older brother, Robert, in the jaw at recess. Robert went about religion in the same methodical, businesslike way he went about everything. Jeremy, however, decided at the tender age of six that he wanted to become a prophet. He’d dress up in a white beard and black robe and quote passages from his Children’s Bible to point out the family’s sins. For example, they washed milk and meat dishes in the same sink, and ate swordfish, which in infancy had scales like a kosher fish should but then lost its scales in adulthood. He began wearing a yarmulke to meals and then all the time. After his bar mitzvah, he attended an Orthodox shul and wore a wrinkled cotton shirt with fringes under his clothes.

From the Hardcover edition.

A LIST OF PLANTS THAT GROW OUT OF THE WAILING WALL

1.HENBANE, or “SHIKARON” (“intoxication” in Hebrew). When ingested, induces a state of deep, colorful hallucination and finally a very pleasant death. Most common plant in the Wall.

2.PODOSNOMA. Roots can crack rocks to draw out water.

3.SICILIAN SNAPDRAGON. Prefers high altitudes.

4.HORSETAIL KNOTGRASS. Antidote for snakebite and the evil eye.

5.THORNY CAPER. Makes an excellent marinade for roast chicken.

6.PHAGNALON. Small and shy.

It was an intolerably hot morning near the end of June. A mother, father, and son named Michaelson floated on a cruise ship off the coast of Haifa, along with the other 251 members of the Millennium Marathon 2000. As they approached the harbor, their ship was briefly turned back by a black military helicopter, chartered to reenact the drama of Holocaust refugees sneaking into Palestine during the British Mandate. The Michiganders offered a light round of confused applause, and as if by command, the helicopter instantly swirled away.

Sweaty, bleary-eyed, and a bit deaf from the chopping of the helicopter, the Michaelsons collected their luggage and duty-free bags and streamed down the gangplanks with the other Michiganders. Aliza, the rabbinic intern, tried unsuccessfully to lead their group in a chorus of “Jerusalem of Gold.” Her lavender song sheets fluttered down the side of the boat into the murky green water of the harbor.

On dry land, they received commemorative T-shirts with a handprint-shaped outline of their state and the message “THE Millennium Marathon 2000! What’s good for the goose is even better for the Michigander!”

“Isn’t that a riot?” said Mrs. Michaelson, fifty-eight years old and often called handsome. She held a shirt up to the chest of her bored-looking son, who clearly did not think it was a riot. Her husband, busy emptying his nose into a hankie, had no opinion. And to tell the truth, Mrs. Michaelson herself didn’t think it was a riot either. She was distracted by the heat as well as the realization that this was the first time she had ever set foot in Asia.

Before she could explore the continent further, their group was confronted by three air-conditioned buses, two unlicensed Russian photographers, who were chased away by the police, and one rabbi. His name was Rabbi Sherman, but he encouraged them to call him Rabbi Rick. He looked younger than Mrs. Michaelson had expected—though actually in his forties, he could have passed for thirty-five—and more attractive than any rabbi had a right to be. He was also unusually hairy. The top of his head, his arms, his hands, the back of his neck, and even his feet, peeking through the gaps in his brown leather sandals, were all covered in black wool.

Rabbi Sherman, riding in the first bus of their caravan, led them to their hotel, which boasted a commanding view of the harbor. Mrs. Michaelson took it in alone on the terrace after dinner. A sultry breeze blew in from the purple water of Haifa harbor, where the crescent moon was reflected as a series of white dashes on the waves. Within minutes, her dress was sticking to the skin under her arms and along the neckline.

Clutching an empty wineglass, Mrs. Michaelson closed her eyes and imagined she was having a religious moment. A trickle of sweat inched its way down between her breasts; a mosquito tickled her ear. “It’s so late. . . .” she murmured.

A high, sharp voice, like a seagull, cried out, “Who’s there?”

Someone moved in the shadows. Mrs. Michaelson made out the wide smile first, a wall of chiseled white teeth. The smile belonged to a short, sharp-chinned woman with pointy elbows jutting out of a glittery tissue-thin shawl. She padded up to Mrs. Michaelson in her bare feet.

“Sherry Sherman,” said the stranger, her right hand thrust forward like a gun.

Mrs. Michaelson, who wasn’t the type to accost strangers minding their own business, gave a bored smile, as if she were placing her order at dinner. When she smiled, her kind gray eyes pressed together so tightly it was impossible to see into them.

“I’m sort of a den mother to you folks,” Sherry said. “Rabbi Rick and I live together in Tel Aviv. No, no, nothing like that. Of course, I’m much too old for him. And there’s one more small matter: he’s my son! By the way, your dress is stunning. Did you find it in New York City? I hope you don’t mind spilling all your secrets.”

“This?” Mrs. Michaelson said, holding out the material so that Sherry Sherman could admire the workmanship more easily. “It’s just something I made. The pattern was easy.”

“You made it?” said Sherry, fluffing her tight curls with the tips of her fingers. She was bony and spry like a cat, not a bit like the tall, strapping rabbi, who plodded ahead of their group with his shoulders thrown back like the Great White Hunter. “I don’t know anyone who still sews. Maybe a button, not a whole dress. You really made it? Now that’s special. But aren’t I interrupting? I heard you talking to someone.”

“I wasn’t talking to anyone . . .” said Mrs. Michaelson, who talked to herself so often that she’d had plenty of practice making excuses.

“Hush! Do you feel that breeze? That’s a typical Middle Eastern cooling breeze blowing in off the Mediterranean. Take a moment to let it soak into your skin.”

Mrs. Michaelson took a moment, but didn’t notice anything particularly special about the breeze. Chatty women made her feel like the chubby, soft-spoken girl she’d been in grade school, always dressed in stiff, frilly dresses suitable for antique dolls.

“You’re here for an adventure. Am I right? In that case, I’ll have to keep my eye on you to see how it turns out. If only I could visit Israel for the first time all over again.” Sherry sighed, then recited, “ ‘If I forget thee, Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning.’ That’s from Psalms.”

“I’ve heard that one,” Mrs. Michaelson said, smashing a mosquito on her neck.

“ ‘In Jerusalem, everyone remembers he’s forgotten something, but he doesn’t remember what it is.’ That’s by Yehuda Amichai, one of our great poets.” Sherry stared directly at Mrs. Michaelson, who looked away, back at the harbor. “You seem to have a case of the jitters, dear. It’s natural. I see it in all you first-timers, especially Americans. Listen, I’ve lived in Israel for six months, so I’m something of an expert now, and I can tell you we’re far safer here than in the States. Street crime’s practically unheard of. Death by tourism? Extremely rare.”

Mrs. Michaelson preferred not to dwell on morbid subjects like death. Someday she would die but, thankfully, when it happened, she wouldn’t be around to know about it.

“If we change how we live, then the terrorists win,” Sherry said with a firm nod. “You’re far more likely to die in a horrible car crash at home than by a bomb in an Israeli marketplace, but do you stop driving? No. You minimize the risk by wearing a seat belt, which, thanks to Ralph Nader, is now standard in all vehicles. Rabbi Rick and I have decided to vote for Nader in November, but he’d never tell you that, because my son makes it a point to stay out of American political debates. Can I ask why you’re holding that wineglass?”

“To calm my nerves” would have been the honest answer. At dinner, Mrs. Michaelson had slipped it into her purse when her son wasn’t looking, in case one of the waiters forgot her warnings and filled the glass by accident. She’d imagined the resulting scene: Jeremy grabbing the glass of wine in a fit of weakness, downing it in a single greedy gulp, and then falling to the floor, where he’d lie twitching like an epileptic.

But how to explain all that to Sherry Sherman, who said, “Oh, I see it’s a sore subject. I never pry,” and padded away.

For two weeks, their troika of air-conditioned buses trekked up and down the Holy Land, from the snows of Mount Hermon (no snow in summer) to the sandy wastes of the Negev (hot, poisonous winds, and dreary scenery).

Mrs. Michaelson applauded for an orchestra of Russian immigrants playing Gershwin at a kibbutz in the Galilee, though she didn’t really like Gershwin. Too showy.

She ate pita pounded thin and then toasted over an open fire by Bedouins in a desert camp in the Negev.

“Good?” they asked.

“Good, good!” she reassured them.

She watched Mr. Michaelson, who’d mysteriously dropped the title “Doctor” when he got sick, rape the Holy Land of its souvenirs: heart-shaped blue-glass eyes, inflatable camels, Dead Sea mud masks, a book of Golda Meir’s favorite falafel recipes, an antique Roman coin that came with a certificate of authenticity.

She received a welcome kit with a miniature cake and an airline-size bottle of kosher red wine (she confiscated Jeremy’s bottle while he was in the shower), a Millennium Marathon Daily Bulletin photocopied on goldenrod paper, and a plastic bottle of from sand to land sand, which Jeremy dumped into her glass of wine one night at dinner to prove he wasn’t the least bit tempted to steal a sip.

She pressed flesh with the mayors of Tel Aviv, Rishon Le-Tzion, and Eilat, where their hotel offered free samples of peppermint foot lotion, which she used to massage her bunions.

She witnessed a phalanx of ten women dressed all in black standing by the side of the highway near the Megiddo junction. Perfectly silent and still, the Women in Black carried signs in Hebrew, English, and Arabic calling for the end of the “occupation.”

She quickly learned the two ways to say “No thanks, I’m stuffed” in Hebrew, a matter of life and death in a country where tourists were apt to be pelted with unwanted extra helpings. The first expression meant “I’ve had enough to eat.” The other, which wasn’t particularly nice, meant “I’m so full I’m going to explode like an Arab.”

She clipped a photo of Ehud Barak from the International Herald Tribune, because he looked exactly like her father when he’d been Barak’s age. Back then, her father woke up at six a.m. to work at his grocery stand, then came home late, his hands chafed raw from washing vegetables in ice water. She loved him, but she used to hate touching his hands.

She posed for a picture beside a camel tied to a parking meter and invited Jeremy, standing a few feet away from everyone as usual with one of his cigarettes, to pose too. And, just for the picture, could he take out the safety pin he’d seen fit to stick through his nose? (There was nothing they could do about the green stripes in his hair, though by pretending to pat him on the head, she often managed to smooth out the sharp edges of his “faux Mohawk,” a pyramid of hair cemented with gel.)

It wasn’t a safety pin.

“It looks like a safety pin,” Mrs. Michaelson said. “What’s the difference?”

Jeremy pulled at the metal, stretching out his nostril. “This is sterilized. Also, for your information, camels aren’t the least bit biblical. They weren’t domesticated until six hundred years after Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.”

At times like this she saw some of her own awkwardness in him, and she couldn’t help laughing.

“Why do I open my mouth?” he said. “You never listen to me anyway.”

So Mrs. Michaelson stood alone by the unbiblical camel, blinked away the beads of perspiration dripping into her eyes, and claimed to be enjoying herself. She recalled the dignity of the Women in Black silently protesting near Megiddo and imagined that by taking the picture she, too, was staging a silent protest.

As soon as the camera flashed, several charming Bedouin boys jumped down from the olive trees and came running at them, shouting, “Money! Money!”

Mostly she sweated. Miserably. They all sweated. Everywhere the Michiganders traveled, guides and drivers and souvenir hawkers told them how unlucky they were to visit Israel during a sharav (Hebrew) or a hamsin (Arabic), a blistering heat wave. These hamsins (most Israelis preferred the Arabic word) scalded the Levant every summer, but there hadn’t been one this bad in a while.

“We didn’t have one so bad for maybe fifty years, giving or taking,” said Baruch, their Israeli driver, as they churned along Highway 1 from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. She preferred Baruch to Igor, who stank of dill. Beside her snored Mr. Michaelson, leaking threads of drool from the corners of his mouth. She was so glad to see him enjoy a good sleep, she didn’t care how he looked. Jeremy sat four rows behind them and pushed up his hair. He’d caused a sensation that morning by pinning his name tag to the zipper of his camouflage cutoffs.

“The last time we had such a hamsin, it was a few weeks after our War for Independence,” said Baruch, his shirt unbuttoned down to his navel. He was always trying to impress her by careening around the edges of sheer cliffs or aiming their bus at fruit stands in picturesque stone alleys. “I was a boy, but I still remember everywhere there was shooting and crazy men with guns in their hands.”

“Terrifying,” she said as if she cared, but she’d heard so many hamsin stories by then, they blended together. She was surprised there was no commemorative T-shirt.

“That’s only the start, my dear Shoshana.” Baruch always called her Shoshana, Hebrew for Rose, though it wasn’t her name. “In a hamsin, a man can get all turned around. Normal becomes crazy and crazy becomes normal.”

Mrs. Michaelson had dreamed of exactly that kind of transformation for her son when she’d signed them up to visit Israel. No luck so far, and now they had only five days left before they returned home. She felt ashamed when she thought of how naïvely she’d pushed them all to come, and at such expense.

Their bus grunted uphill, slouching beneath a heraldic banner across Highway 1: Peugeot welcomed them to Jerusalem, Mrs. Michaelson’s final, though perhaps best, hope. If Jeremy was going to find himself, where could be more fitting than the capital of the Jews’ home turf?

Almost fifteen years earlier, Mrs. Michaelson had transferred her two boys to Jewish Day School after an economically and educationally challenged African American boy had punched Jeremy’s older brother, Robert, in the jaw at recess. Robert went about religion in the same methodical, businesslike way he went about everything. Jeremy, however, decided at the tender age of six that he wanted to become a prophet. He’d dress up in a white beard and black robe and quote passages from his Children’s Bible to point out the family’s sins. For example, they washed milk and meat dishes in the same sink, and ate swordfish, which in infancy had scales like a kosher fish should but then lost its scales in adulthood. He began wearing a yarmulke to meals and then all the time. After his bar mitzvah, he attended an Orthodox shul and wore a wrinkled cotton shirt with fringes under his clothes.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Aaron Hamburger takes a deceptively simple situation–an American family visiting Israel–and spins a rich, complex, often profound comedy about religion, sex, politics, and love. He has an excellent eye and ear for the absurd, but more important, genuine sympathy for the hopes and confusions all people share under our cartoon surfaces. And nobody has written a better mother and son.”

–Christopher Bram, author of Lives of the Circus Animals and Gods and Monsters

“Aaron Hamburger elucidates a truth about the search for faith: that the journey forward is seldom blissful. In Faith for Beginners, Hamburger peoples a volatile political setting with a handful of characters pursuing transcendence–through culture, through mortality, through the spirit, through the flesh. For Hamburger’s seekers, what transpires is risky, chaotic, and surprisingly tender. For his readers, exhilarating.”

–Dave King, author of The Ha-Ha

From the Hardcover edition.

–Christopher Bram, author of Lives of the Circus Animals and Gods and Monsters

“Aaron Hamburger elucidates a truth about the search for faith: that the journey forward is seldom blissful. In Faith for Beginners, Hamburger peoples a volatile political setting with a handful of characters pursuing transcendence–through culture, through mortality, through the spirit, through the flesh. For Hamburger’s seekers, what transpires is risky, chaotic, and surprisingly tender. For his readers, exhilarating.”

–Dave King, author of The Ha-Ha

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

The author of "The View from Stalin's Head" now offers a humorous and moving novel about an American family whose vacation to Jerusalem goes terribly awry.

Premii

- Lambda Literary Awards Nominee, 2005