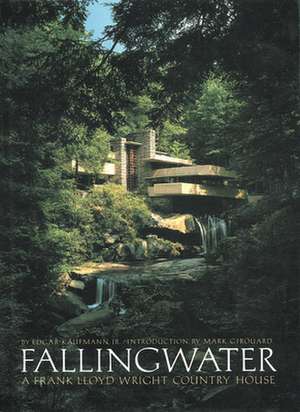

Fallingwater: A Frank Lloyd Wright Country House

Autor Edgar Kaufmann, Jr.en Limba Engleză Hardback – 28 oct 1986

Considered Frank Lloyd Wright's domestic masterpiece, Fallingwater is recognized worldwide as the paradigm of organic architecture. Here, in beautiful photographs, the first as-built measured plans, and an intimate narrative by a key figure, is the fascinating story of this masterwork.

Fallingwater is the most famous modern house in America. Indeed, readers of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects voted it the best American building of the last 125 years! Annually, more than 128,000 visitors seek out Fallingwater in its remote mountain site in southwestern Pennsylvania. Considered Frank Lloyd Wright's domestic masterpiece, the house is recognized worldwide as the paradigm of organic architecture, where a building becomes an integral part of its natural setting.

This charming and provocative book is the work of the man best qualified to undertake it, who was both apprentice to Wright and son of the man who commissioned the house. Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., closely followed the planning and construction of Fallingwater, and lived in the house on weekends and vacations for twenty-seven years-until, following the deaths of his parents, he gave the house in 1963 to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy to hold for public enjoyment and appreciation.

This is a personal, almost intimate record of one man's fifty-year relationship to a work of genius that only gradually revealed its complexities and originality. With full appreciation of the intentions of both architect and client, Mr. Kaufmann described this remarkable building in detail, telling of its extraordinary virtues but not failing to reveal its faults. One section of the book focuses on the realities of Fallingwater as architecture. A famous building right from its beginnings (only partly because it was Wright's first significant commission in more than a decade), Fallingwater has accumulated considerable publicity and analysis-much of it off the mark. Mr. Kaufmann outlined and dealt with the common misunderstandings that have obscured the building's true values and supplied accurate information and interpretations. In another section Mr. Kaufmann provided an in-depth essay on the subtleties of Fallingwater, the ideology underlying its esthetics. A key element of this is the close interweaving of the house and its rugged, challenging setting, which he explicated in fascinating detail.

The author maintained throughout the direct approach of one who knew and loved Fallingwater. As an apprentice and loyal admirer of the architect, Mr. Kaufmann was well attuned to the architecture. And as a retired professor of architectural history and frequent lecturer and panelist, he had considerable experience in presenting and interpreting Wright's ideas. Thoroughly versed in the books, articles, drawings, and buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mr. Kaufmann was eminently situated to place Fallingwater in that context. This unique record was presented in celebration of Fallingwater's fiftieth anniversary.

Special features of this volume include: numerous never-before published photographs of the house under construction, during its entire history, and of the family in residence; a room-by-room pictorial survey in full color taken especially for this volume; isometric architectural perspectives that explain visually how the house was constructed; and the first accurate, measured plans of the house as built.

Fallingwater is the most famous modern house in America. Indeed, readers of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects voted it the best American building of the last 125 years! Annually, more than 128,000 visitors seek out Fallingwater in its remote mountain site in southwestern Pennsylvania. Considered Frank Lloyd Wright's domestic masterpiece, the house is recognized worldwide as the paradigm of organic architecture, where a building becomes an integral part of its natural setting.

This charming and provocative book is the work of the man best qualified to undertake it, who was both apprentice to Wright and son of the man who commissioned the house. Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., closely followed the planning and construction of Fallingwater, and lived in the house on weekends and vacations for twenty-seven years-until, following the deaths of his parents, he gave the house in 1963 to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy to hold for public enjoyment and appreciation.

This is a personal, almost intimate record of one man's fifty-year relationship to a work of genius that only gradually revealed its complexities and originality. With full appreciation of the intentions of both architect and client, Mr. Kaufmann described this remarkable building in detail, telling of its extraordinary virtues but not failing to reveal its faults. One section of the book focuses on the realities of Fallingwater as architecture. A famous building right from its beginnings (only partly because it was Wright's first significant commission in more than a decade), Fallingwater has accumulated considerable publicity and analysis-much of it off the mark. Mr. Kaufmann outlined and dealt with the common misunderstandings that have obscured the building's true values and supplied accurate information and interpretations. In another section Mr. Kaufmann provided an in-depth essay on the subtleties of Fallingwater, the ideology underlying its esthetics. A key element of this is the close interweaving of the house and its rugged, challenging setting, which he explicated in fascinating detail.

The author maintained throughout the direct approach of one who knew and loved Fallingwater. As an apprentice and loyal admirer of the architect, Mr. Kaufmann was well attuned to the architecture. And as a retired professor of architectural history and frequent lecturer and panelist, he had considerable experience in presenting and interpreting Wright's ideas. Thoroughly versed in the books, articles, drawings, and buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, Mr. Kaufmann was eminently situated to place Fallingwater in that context. This unique record was presented in celebration of Fallingwater's fiftieth anniversary.

Special features of this volume include: numerous never-before published photographs of the house under construction, during its entire history, and of the family in residence; a room-by-room pictorial survey in full color taken especially for this volume; isometric architectural perspectives that explain visually how the house was constructed; and the first accurate, measured plans of the house as built.

Preț: 390.45 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 586

Preț estimativ în valută:

74.74€ • 78.52$ • 62.81£

74.74€ • 78.52$ • 62.81£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 19 februarie-05 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780896596627

ISBN-10: 0896596621

Pagini: 190

Dimensiuni: 241 x 330 x 32 mm

Greutate: 1.68 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

ISBN-10: 0896596621

Pagini: 190

Dimensiuni: 241 x 330 x 32 mm

Greutate: 1.68 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Cuprins

Table of Contents from: Fallingwater

Introduction:

The House and the Natural Landscape: A Prelude to Fallingwater by Mark Girouard

Foreword:

Fallingwater, Known and Unknown

Recollecting Fallingwater:

Drifting Toward Wright

How Fallingwater Began

The Faults of Fallingwater

Living with Fallingwater

Responsibilities

Rewards and Opportunities

Fallingwater in a New Role

Entry and Main Floor:

Pictorial

Realities at Fallingwater:

What Fallingwater Is–and Is Not

Measured Drawings

The Adaptability of Wrights Architecture

Wright's Systems–and Mutations

Presenting Continuous Space

Fallingwater in Its Setting

Inside Fallingwater

Upper Floors and Guest Wing:

Pictorial

Ideas of Fallingwater:

Images

What Images Do Not Tell

Afterword:

Fallingwater's Future

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

Photography Credits

Introduction:

The House and the Natural Landscape: A Prelude to Fallingwater by Mark Girouard

Foreword:

Fallingwater, Known and Unknown

Recollecting Fallingwater:

Drifting Toward Wright

How Fallingwater Began

The Faults of Fallingwater

Living with Fallingwater

Responsibilities

Rewards and Opportunities

Fallingwater in a New Role

Entry and Main Floor:

Pictorial

Realities at Fallingwater:

What Fallingwater Is–and Is Not

Measured Drawings

The Adaptability of Wrights Architecture

Wright's Systems–and Mutations

Presenting Continuous Space

Fallingwater in Its Setting

Inside Fallingwater

Upper Floors and Guest Wing:

Pictorial

Ideas of Fallingwater:

Images

What Images Do Not Tell

Afterword:

Fallingwater's Future

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Index

Photography Credits

Recenzii

"…never has [Kaufmann's] account been so astute and revealing, and never has the resulting building been so brilliantly portrayed as in this volume…As the reader views Fallingwater in a series of stunning illustrations, Kaufmann gives a more intimate view of what the house has meant to him personally and what role it has played in assuring Wright an enduring place in architectural history." — Booklist

"An engaging, intimate, sumptuous appreciation of Wright's 1936 house in Bear Run, Pennsylvania…[Kaufmann] is able to explain the intentions of architect and client, and writes with both feeling and critical knowledge, having lived in and with the masterpiece all his life. A work of loving scholarship, beautifully presented, Fallingwater is highly recommended for all collections." — Library Journal

"An engaging, intimate, sumptuous appreciation of Wright's 1936 house in Bear Run, Pennsylvania…[Kaufmann] is able to explain the intentions of architect and client, and writes with both feeling and critical knowledge, having lived in and with the masterpiece all his life. A work of loving scholarship, beautifully presented, Fallingwater is highly recommended for all collections." — Library Journal

Notă biografică

Edgar J. Kaufmann, Jr. (1910-1989), entered Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin Fellowship in 1934. During Fallingwater's design and construction, he often served as intermediary between his parents and Wright. Subsequently, Mr. Kaufmann joined the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, became editorial adviser to Encyclopaedia Britannica, and taught at Columbia University. Mr. Kaufmann was the author, editor, or contributor to several design and architecture books and wrote numerous articles. He served on the Editorial Board of the Architectural History Foundation.

Extras

Excerpt from: Fallingwater

Introduction: The House and the Natural Landscape: A Prelude to Fallingwater by Mark Girouard

A charming drawing by Thomas Hearne shows Sir George Beaumont and Joseph Farington sketching a waterfall in the Lake District, sometime in the 1770s. Waterfalls were being visited and sketched all over the British Isles at this period. But although gentlemen of taste sketched waterfalls, they did not build houses by them, still less over them. Nonetheless, a continuous thread connects Sir George Beaumont, sketching his waterfall in the 1770s, to Edgar J. Kaufmann, commissioning Frank Lloyd Wright to build Fallingwater in the 1930s. Between them lies a gradual development of the romantic imagination, and of attitudes to the natural landscape and to the problem of how buildings should, or should not, be fitted into it.

In the eighteenth century, when English travelers first began to appreciate natural scenery, and to tour the mountains, lakes, rocks, waterfalls, and wild places of the British Isles, their attitude was by no means uncritical. For them "nature" was the supreme arbiter, but by "nature" they understood a Platonic ideal that actual natural scenery did not necessarily live up to. They had come to their appreciation by way of art and poetry, and traveled with minds conditioned by the way artists had painted wild landscapes, or poets had written about them, in both cases selecting and adjusting in order to compose a picture or a poem. A guide to the Lake District, first published in 1778, set out to take tourists "from the delicate touches of Claude, verified in Coniston Lake, to the noble scenes of Poussin, exhibited on Windermere-water, and from there to the stupendous romantic ideas of Salvator Rosa, realized in the Lake of Derwent." When looking at a view, travelers would pass judgment on it, and mentally readjust it if necessary.

Scenery was condemned for being too simple or too bare. A landscape of heather and rocks needed trees to break its outlines and give it light and shade. "Mere rocks," wrote Thomas Whately in his Observations on Modern Gardening (1770), "may surprise, but can hardly please; they are too far removed from common life, too barren and inhospitable, rather desolate than solitary, and more horrid than terrible." Rocks were improved by water falling over or running through them; this produced a broken light and a broken sound that was both picturesque and pleasing. Trees, rocks, and water joined together in the right proportions made up a picturesque composition.

Conventions developed about what did, or did not, go with particular views or features. Some types of buildings harmonized with waterfalls: Whately, for instance, described with approval "an iron forge, covered with a black cloud of smoke, and surrounded with half-burned ore" next to the "roar of a waterfall" on the River Wye. It suggested "the ideas of force or of danger" and was "perfectly compatible with the wildest romantic situations." But a regular house next to a waterfall was a solecism: it spoiled the picture because it had the wrong associations. Looked at the other way, a wild landscape coming right up to a house spoiled the house. "And while rough thickets shade the lonely glen, Let culture smile upon the haunts of men," wrote Richard Payne Knight in his poem The Landscape (1795). A house of any size needed a park, and a park while it should never be formal, had "a character distinct from a forest; for while we admire, and even imitate, the romantic wildness of nature, we ought never to forget that a park is the habitation of men." (Humphry Repton, An Enquiry into the Changes in Landscape Gardening, 1806)

So it came about that when eighteenth-century devotees of the picturesque painted or drew "the romantic wildness of nature" they depicted it without domestic accompaniments; when they imitated it, they imitated it out of sight of their houses; and when they went to live in it, they inserted an intermediary zone of culture and cultivation between house and wilderness. Hafod in Wales, for instance, which was the most famous wild demesne in eighteenth-century Britain, was renowned for its waterfalls. But none of these was in sight of the house, which was built in a more pastoral setting of greensward and grazing cattle.

Country-house owners whose property did not happen to contain waterfalls not infrequently constructed an artificial one. At Bowood, in Wiltshire, Lord Shelburne made one at the end of an artificial lake, after the model of a picture by Poussin. Lord Stamford’s new cascade at Enville in Staffordshire was described with enthusiasm by Joseph Heely: "I think I never saw so fine an effect from light and shade, as is here produced by the gloom of evergreens and other trees, and the peculiar brightness of the foaming water." (Letters on the Beauties of Hagley, Envil and the Leasowes, 1777) But neither fall was in sight of the house. The most that was considered suitable to embellish a waterfall was a statue or inscription, perhaps to a departed relative or friend, suitable to the mood of gentle melancholy induced by the sound of water; or a seat from which to admire it. The latter had to be in the right mode, however, like that at the Leasowes, near Enville: "a rude seat, composed of stone, under rugged roots."

Unlike ordinary houses, castles, especially ruined castles, were also considered appropriate features in wild scenery. They definitely had the right romantic connotations. But sometimes castles were still lived in, and sometimes they needed to be rebuilt. Culzean Castle in Ayrshire, for instance, was an old fortified house on a cliff top overlooking the sea. Its position was superb, its family associations were valued, but as a house the building failed to meet the late-eighteenth-century standards of accommodation and comfort. Between 1777 and 1792 it was rebuilt to the designs of Robert Adam, but in his own individual version of a castle style, in sympathy with its site. The new house rose straight from the cliffs, like the old one.

Culzean pioneered a fresh approach, based on the idea that the architecture of a new house could be adapted to fit it to a wild situation. In the early nineteenth century a number of such houses were built, on dramatic sites or in wild settings, even when there had been no house there before. Normally they were built in a castle manner, but some, like Dunglass in Haddingtonshire, were built in the classical style, though on an asymmetric plan and with a broken outline, to fit the site. Such houses continued to be built through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s the architect Richard Norman Shaw established his reputation by designing Leyswood in Sussex, and Cragside in Northumberland, on dramatic rocky sites to which the houses played up with fragmented plans, soaring verticals, and picturesquely broken roofs. Shaw was consciously continuing the picturesque tradition, but, on the whole, new houses in this kind of position were built comparatively seldom in the British Isles.

When clients or architects did opt for a wild site it was usually an elevated one, with the house rising out of wild nature rather than melting into it. This was partly because such houses were built for people of position, who wanted their place of residence to have a degree of importance; but also because houses on higher land had a view, and enclosed low-lying situations were thought to be unhealthy. It was probably for these reasons that houses down by waterfalls were a rarity.

There was one building type, however, that could appropriately be designed to melt into its surroundings. This was the cottage. An interest in natural scenery had almost inevitably led to an appreciation of the way in which nature worked on and weathered man-made structures. Ruins appealed to eighteenth-century eyes in part because they were usually overgrown with moss and creepers. Artists on the look-out for picturesque effects also began to take an interest in old cottages, particularly when they were so dilapidated that nature seemed to be taking them over, to the delight of the artist if not of the inhabitants. "Moral and picturesque ideas do not always coincide," as William Gilpin put it. (Observations on Several Parts of England, 1808)

From the mid-eighteenth century onward similar effects, suitably adapted to cope with problems of keeping out wind and weather, began to be incorporated into new buildings. Thatched roofs, rough undressed stonework, and creeper-clad porches and verandahs made of untrimmed branches, often with the bark left on them, were especially popular. To begin with these elements were confined to buildings such as grottoes, hermitages, and bathhouses, which were built as features in a park rather than to be lived in. But by the end of the eighteenth century they were being used for residential cottages. These included elaborate "cottages ornées," designed for the residence of ladies and gentlemen themselves, especially when they were on holiday by the seaside, or in retreat from the responsibilities of an active life. In such situations dignity and importance were not called for; people went to live in a cottage ornée specifically in order to feel that they were escaping from the conventions of society and tasting something of the rural innocence that poets had always associated with cottage life: "the insinuating effusions of the muse, that true happiness is only to be found in a sequestered and rural life," as William Heely put it.

Perhaps the most alluring cottage ornée ever built is the so-called Swiss Cottage at Cahir, in southern Ireland. It was designed, possibly by John Nash, for the Earl of Glengall in about 1820. Its position is a singularly beautiful and peaceful one, on a low rise above a reach of the River Suir. The cottage was, and is, almost swallowed up by the woods that envelop it, and by its own thatched roofs and rustic verandahs. Inside, however, a selection of highly fashionable French wallpapers kept Lord Glengall in touch with metropolitan society.

Swiss Cottage is worth comparing with the "cabin" built for or by Jean-Jacques Rousseau near the chateau of Ermenonville, where he spent the last years of his life. The cabin, as described in an anonymous Tour to Ermenonville (1785), was "built against the rock and thatched with heath. Within, besides a plain and unornamented fireplace, we found a seat cut out of the rock, and covered with moss, a small table and two wicker chairs." On the door was the inscription "It is on the tops of mountains that man contemplates the face of nature with real delight. There it is that, in conference with the fruitful parent of all things, he receives from her those all powerful inspirations, which lift the mind above the sphere of error and prejudice."

The cabin clearly related to rustic hermitages in English gentlemen’s parks, but it related with a difference. For one thing it was not in a park; it was on a hilltop in what contemporaries called a "desert," a stretch of completely unimproved heath a mile or two from the chateau. Round the chateau itself its owner had created conventionally picturesque grounds in the English manner, complete with an artificial cascade and a monument to Rousseau, erected after his death on an island in a lake. The English visitor was struck by the contrast between all this and the adjacent "desert." Rousseau himself had used the cabin on "excursions, during which he loved to read the great book of nature, on the tops of mountains, or in the depths of some venerable forest."

A new note is being struck, the note of the Romantic Movement, which grew out of appreciation of the picturesque, overlapped it, but was essentially different from it. Wild natural scenery ceased to be looked at with a critical eye, as something to be enjoyed but also improved, in the light of a literary or artistic tradition; the simple life ceased to be seen as a form of agreeable play-acting. Nature, in the sense of actual wild landscape not a lost ideal, was now to be approached with reverence, as a means of regeneration and a source of mystical experience. Rousseau was a pioneer, but in the first half of the nineteenth century the attitudes he had helped to inaugurate spread through the Western world.

The idea of the picturesque had inevitably come to America, but its American devotees were at a disadvantage. America had no ruined abbeys, castles, or temples, nor landscapes rich with suitable associations. For a time Americans felt deprived when they looked at their own scenery. The Romantic Movement reversed the situation. "All nature is here new to art," English-born Thomas Cole wrote of the Catskill Mountains in the 1830s, in celebration not in a mood of despondency. "No Tivolis, Ternis, Mont Blancs, Plinlimmons, hackneyed and worn by the pencils of hundreds, but primeval forests, virgin lakes and waterfalls." (Quoted by Charles Rockwell, The Catskill Mountains, 1873.) "Here," wrote American-born Washington Irving in Home Authors and Home Artists, "are locked up mighty forests which have never been invaded by the axe; deep umbrageous valleys where the virgin soil has never been outraged by the plough; bright streams flowing in untasked idleness, unburthened by commerce, unchecked by the mill. This mountain zone is in fact the great poetical zone of our country."

As early as 1823-24 the hotel known as the Catskill Mountain House was built on the edge of a cliff in the heart of the range. Forty years later it was still going strong, and being celebrated in verse by Charles Rockwell:

There it stands, to bless the pilgrim / From the city’s heated homes / Worn and weary with life’s contest / To this mountain height he comes.

By the middle decades of the century spreading railways and growing cities were bringing more and more visitors to mountainous or wild country all over America. Its apparently inexhaustible wealth of wild landscape was accepted as one of its chief glories; so was the role of this landscape as a source of cleansing, refreshment, and spiritual recharging for tired city-dwellers.

The summer rush to the wilds brought architectural problems. A tent and a campfire may have been the ideal equipment with which to commune with nature, but more permanent forms of settlement inevitably developed, even if they continued to be called "camps." What were these to look like, and how could they best be fitted into wild surroundings? Any idea that wild nature could or should be "improved" had been jettisoned, nor was there any desire to interpose a barrier of cultivation between dwelling and surroundings. The Catskill Mountain House seemed to have been dropped on the edge of its precipice in an almost unaltered landscape. But the hotel itself was a porticoed neoclassical building, such as could have been found on the edge of dozens of American cities. Thomas Cole, in his superb picture of hotel and mountains, had to paint the hotel narrow-end on, in order to keep it from being too obtrusive.

For a time experiments were made with the Swiss-chalet style, as on occasions in England. Later on in the century Norman Shaw’s houses exerted a powerful influence on American seaside and holiday architecture, mainly on the strength of the brilliant drawings with which they had been illustrated in English architectural magazines. The rocky settings of Cragside and Leyswood were not all that different from the rocky coastline of New England; both Shaw’s architecture and the style of draftsmanship with which it was presented are immediately recognizable in Eldon Deane’s drawings of summer cottages at Manchester-by-the-Sea. One of them was even called Kragsyde.

But in these and other summer cottages up and down the coast Shaw’s architecture was already undergoing a process of simplification, designed to make it more "natural." Boulders were incorporated into foundations as well as left littered over the surrounding ground. Detail was eliminated and the houses covered with a skin of shingles that rapidly weathered to a color in harmony with their setting. Inside, Shaw’s great inglenook fireplaces were simplified until they became caves of rough-hewn stone. An extra repertory of forms was drawn from America’s brand of natural architecture, the log cabin. It was a form of construction that both made sense in practical terms and had the right connotations; it became especially popular for camps in the Adirondacks, and other mountain districts.

By the early 1900s there were local and individual variations, but a brotherhood of plan, materials, motifs, and descriptive language united holiday houses and camps in wild country all over North America. "The outside will weather to natures gray, which, combined with the natural effect of the porch and the rough stonework will cause the building to blend into the landscape." The description (from W. T. Comstock’s Bungalows, Camps and Mountain Houses, 1908) is of a holiday house on the St. Lawrence River, but similar descriptions were being applied to Adirondack camps, or weekend cottages on Signal Mountain in Tennessee. Boulders or rough-hewn stonework were de rigueur for fireplaces as well as foundations and chimneystacks, especially for the great stone fireplace that invariably dominated the living room. Walls were normally of timber, either shingle-clad or of exposed logs, carrying the mark of the adze or sometimes with the bark left on them…

Introduction: The House and the Natural Landscape: A Prelude to Fallingwater by Mark Girouard

A charming drawing by Thomas Hearne shows Sir George Beaumont and Joseph Farington sketching a waterfall in the Lake District, sometime in the 1770s. Waterfalls were being visited and sketched all over the British Isles at this period. But although gentlemen of taste sketched waterfalls, they did not build houses by them, still less over them. Nonetheless, a continuous thread connects Sir George Beaumont, sketching his waterfall in the 1770s, to Edgar J. Kaufmann, commissioning Frank Lloyd Wright to build Fallingwater in the 1930s. Between them lies a gradual development of the romantic imagination, and of attitudes to the natural landscape and to the problem of how buildings should, or should not, be fitted into it.

In the eighteenth century, when English travelers first began to appreciate natural scenery, and to tour the mountains, lakes, rocks, waterfalls, and wild places of the British Isles, their attitude was by no means uncritical. For them "nature" was the supreme arbiter, but by "nature" they understood a Platonic ideal that actual natural scenery did not necessarily live up to. They had come to their appreciation by way of art and poetry, and traveled with minds conditioned by the way artists had painted wild landscapes, or poets had written about them, in both cases selecting and adjusting in order to compose a picture or a poem. A guide to the Lake District, first published in 1778, set out to take tourists "from the delicate touches of Claude, verified in Coniston Lake, to the noble scenes of Poussin, exhibited on Windermere-water, and from there to the stupendous romantic ideas of Salvator Rosa, realized in the Lake of Derwent." When looking at a view, travelers would pass judgment on it, and mentally readjust it if necessary.

Scenery was condemned for being too simple or too bare. A landscape of heather and rocks needed trees to break its outlines and give it light and shade. "Mere rocks," wrote Thomas Whately in his Observations on Modern Gardening (1770), "may surprise, but can hardly please; they are too far removed from common life, too barren and inhospitable, rather desolate than solitary, and more horrid than terrible." Rocks were improved by water falling over or running through them; this produced a broken light and a broken sound that was both picturesque and pleasing. Trees, rocks, and water joined together in the right proportions made up a picturesque composition.

Conventions developed about what did, or did not, go with particular views or features. Some types of buildings harmonized with waterfalls: Whately, for instance, described with approval "an iron forge, covered with a black cloud of smoke, and surrounded with half-burned ore" next to the "roar of a waterfall" on the River Wye. It suggested "the ideas of force or of danger" and was "perfectly compatible with the wildest romantic situations." But a regular house next to a waterfall was a solecism: it spoiled the picture because it had the wrong associations. Looked at the other way, a wild landscape coming right up to a house spoiled the house. "And while rough thickets shade the lonely glen, Let culture smile upon the haunts of men," wrote Richard Payne Knight in his poem The Landscape (1795). A house of any size needed a park, and a park while it should never be formal, had "a character distinct from a forest; for while we admire, and even imitate, the romantic wildness of nature, we ought never to forget that a park is the habitation of men." (Humphry Repton, An Enquiry into the Changes in Landscape Gardening, 1806)

So it came about that when eighteenth-century devotees of the picturesque painted or drew "the romantic wildness of nature" they depicted it without domestic accompaniments; when they imitated it, they imitated it out of sight of their houses; and when they went to live in it, they inserted an intermediary zone of culture and cultivation between house and wilderness. Hafod in Wales, for instance, which was the most famous wild demesne in eighteenth-century Britain, was renowned for its waterfalls. But none of these was in sight of the house, which was built in a more pastoral setting of greensward and grazing cattle.

Country-house owners whose property did not happen to contain waterfalls not infrequently constructed an artificial one. At Bowood, in Wiltshire, Lord Shelburne made one at the end of an artificial lake, after the model of a picture by Poussin. Lord Stamford’s new cascade at Enville in Staffordshire was described with enthusiasm by Joseph Heely: "I think I never saw so fine an effect from light and shade, as is here produced by the gloom of evergreens and other trees, and the peculiar brightness of the foaming water." (Letters on the Beauties of Hagley, Envil and the Leasowes, 1777) But neither fall was in sight of the house. The most that was considered suitable to embellish a waterfall was a statue or inscription, perhaps to a departed relative or friend, suitable to the mood of gentle melancholy induced by the sound of water; or a seat from which to admire it. The latter had to be in the right mode, however, like that at the Leasowes, near Enville: "a rude seat, composed of stone, under rugged roots."

Unlike ordinary houses, castles, especially ruined castles, were also considered appropriate features in wild scenery. They definitely had the right romantic connotations. But sometimes castles were still lived in, and sometimes they needed to be rebuilt. Culzean Castle in Ayrshire, for instance, was an old fortified house on a cliff top overlooking the sea. Its position was superb, its family associations were valued, but as a house the building failed to meet the late-eighteenth-century standards of accommodation and comfort. Between 1777 and 1792 it was rebuilt to the designs of Robert Adam, but in his own individual version of a castle style, in sympathy with its site. The new house rose straight from the cliffs, like the old one.

Culzean pioneered a fresh approach, based on the idea that the architecture of a new house could be adapted to fit it to a wild situation. In the early nineteenth century a number of such houses were built, on dramatic sites or in wild settings, even when there had been no house there before. Normally they were built in a castle manner, but some, like Dunglass in Haddingtonshire, were built in the classical style, though on an asymmetric plan and with a broken outline, to fit the site. Such houses continued to be built through the nineteenth century. In the 1870s the architect Richard Norman Shaw established his reputation by designing Leyswood in Sussex, and Cragside in Northumberland, on dramatic rocky sites to which the houses played up with fragmented plans, soaring verticals, and picturesquely broken roofs. Shaw was consciously continuing the picturesque tradition, but, on the whole, new houses in this kind of position were built comparatively seldom in the British Isles.

When clients or architects did opt for a wild site it was usually an elevated one, with the house rising out of wild nature rather than melting into it. This was partly because such houses were built for people of position, who wanted their place of residence to have a degree of importance; but also because houses on higher land had a view, and enclosed low-lying situations were thought to be unhealthy. It was probably for these reasons that houses down by waterfalls were a rarity.

There was one building type, however, that could appropriately be designed to melt into its surroundings. This was the cottage. An interest in natural scenery had almost inevitably led to an appreciation of the way in which nature worked on and weathered man-made structures. Ruins appealed to eighteenth-century eyes in part because they were usually overgrown with moss and creepers. Artists on the look-out for picturesque effects also began to take an interest in old cottages, particularly when they were so dilapidated that nature seemed to be taking them over, to the delight of the artist if not of the inhabitants. "Moral and picturesque ideas do not always coincide," as William Gilpin put it. (Observations on Several Parts of England, 1808)

From the mid-eighteenth century onward similar effects, suitably adapted to cope with problems of keeping out wind and weather, began to be incorporated into new buildings. Thatched roofs, rough undressed stonework, and creeper-clad porches and verandahs made of untrimmed branches, often with the bark left on them, were especially popular. To begin with these elements were confined to buildings such as grottoes, hermitages, and bathhouses, which were built as features in a park rather than to be lived in. But by the end of the eighteenth century they were being used for residential cottages. These included elaborate "cottages ornées," designed for the residence of ladies and gentlemen themselves, especially when they were on holiday by the seaside, or in retreat from the responsibilities of an active life. In such situations dignity and importance were not called for; people went to live in a cottage ornée specifically in order to feel that they were escaping from the conventions of society and tasting something of the rural innocence that poets had always associated with cottage life: "the insinuating effusions of the muse, that true happiness is only to be found in a sequestered and rural life," as William Heely put it.

Perhaps the most alluring cottage ornée ever built is the so-called Swiss Cottage at Cahir, in southern Ireland. It was designed, possibly by John Nash, for the Earl of Glengall in about 1820. Its position is a singularly beautiful and peaceful one, on a low rise above a reach of the River Suir. The cottage was, and is, almost swallowed up by the woods that envelop it, and by its own thatched roofs and rustic verandahs. Inside, however, a selection of highly fashionable French wallpapers kept Lord Glengall in touch with metropolitan society.

Swiss Cottage is worth comparing with the "cabin" built for or by Jean-Jacques Rousseau near the chateau of Ermenonville, where he spent the last years of his life. The cabin, as described in an anonymous Tour to Ermenonville (1785), was "built against the rock and thatched with heath. Within, besides a plain and unornamented fireplace, we found a seat cut out of the rock, and covered with moss, a small table and two wicker chairs." On the door was the inscription "It is on the tops of mountains that man contemplates the face of nature with real delight. There it is that, in conference with the fruitful parent of all things, he receives from her those all powerful inspirations, which lift the mind above the sphere of error and prejudice."

The cabin clearly related to rustic hermitages in English gentlemen’s parks, but it related with a difference. For one thing it was not in a park; it was on a hilltop in what contemporaries called a "desert," a stretch of completely unimproved heath a mile or two from the chateau. Round the chateau itself its owner had created conventionally picturesque grounds in the English manner, complete with an artificial cascade and a monument to Rousseau, erected after his death on an island in a lake. The English visitor was struck by the contrast between all this and the adjacent "desert." Rousseau himself had used the cabin on "excursions, during which he loved to read the great book of nature, on the tops of mountains, or in the depths of some venerable forest."

A new note is being struck, the note of the Romantic Movement, which grew out of appreciation of the picturesque, overlapped it, but was essentially different from it. Wild natural scenery ceased to be looked at with a critical eye, as something to be enjoyed but also improved, in the light of a literary or artistic tradition; the simple life ceased to be seen as a form of agreeable play-acting. Nature, in the sense of actual wild landscape not a lost ideal, was now to be approached with reverence, as a means of regeneration and a source of mystical experience. Rousseau was a pioneer, but in the first half of the nineteenth century the attitudes he had helped to inaugurate spread through the Western world.

The idea of the picturesque had inevitably come to America, but its American devotees were at a disadvantage. America had no ruined abbeys, castles, or temples, nor landscapes rich with suitable associations. For a time Americans felt deprived when they looked at their own scenery. The Romantic Movement reversed the situation. "All nature is here new to art," English-born Thomas Cole wrote of the Catskill Mountains in the 1830s, in celebration not in a mood of despondency. "No Tivolis, Ternis, Mont Blancs, Plinlimmons, hackneyed and worn by the pencils of hundreds, but primeval forests, virgin lakes and waterfalls." (Quoted by Charles Rockwell, The Catskill Mountains, 1873.) "Here," wrote American-born Washington Irving in Home Authors and Home Artists, "are locked up mighty forests which have never been invaded by the axe; deep umbrageous valleys where the virgin soil has never been outraged by the plough; bright streams flowing in untasked idleness, unburthened by commerce, unchecked by the mill. This mountain zone is in fact the great poetical zone of our country."

As early as 1823-24 the hotel known as the Catskill Mountain House was built on the edge of a cliff in the heart of the range. Forty years later it was still going strong, and being celebrated in verse by Charles Rockwell:

There it stands, to bless the pilgrim / From the city’s heated homes / Worn and weary with life’s contest / To this mountain height he comes.

By the middle decades of the century spreading railways and growing cities were bringing more and more visitors to mountainous or wild country all over America. Its apparently inexhaustible wealth of wild landscape was accepted as one of its chief glories; so was the role of this landscape as a source of cleansing, refreshment, and spiritual recharging for tired city-dwellers.

The summer rush to the wilds brought architectural problems. A tent and a campfire may have been the ideal equipment with which to commune with nature, but more permanent forms of settlement inevitably developed, even if they continued to be called "camps." What were these to look like, and how could they best be fitted into wild surroundings? Any idea that wild nature could or should be "improved" had been jettisoned, nor was there any desire to interpose a barrier of cultivation between dwelling and surroundings. The Catskill Mountain House seemed to have been dropped on the edge of its precipice in an almost unaltered landscape. But the hotel itself was a porticoed neoclassical building, such as could have been found on the edge of dozens of American cities. Thomas Cole, in his superb picture of hotel and mountains, had to paint the hotel narrow-end on, in order to keep it from being too obtrusive.

For a time experiments were made with the Swiss-chalet style, as on occasions in England. Later on in the century Norman Shaw’s houses exerted a powerful influence on American seaside and holiday architecture, mainly on the strength of the brilliant drawings with which they had been illustrated in English architectural magazines. The rocky settings of Cragside and Leyswood were not all that different from the rocky coastline of New England; both Shaw’s architecture and the style of draftsmanship with which it was presented are immediately recognizable in Eldon Deane’s drawings of summer cottages at Manchester-by-the-Sea. One of them was even called Kragsyde.

But in these and other summer cottages up and down the coast Shaw’s architecture was already undergoing a process of simplification, designed to make it more "natural." Boulders were incorporated into foundations as well as left littered over the surrounding ground. Detail was eliminated and the houses covered with a skin of shingles that rapidly weathered to a color in harmony with their setting. Inside, Shaw’s great inglenook fireplaces were simplified until they became caves of rough-hewn stone. An extra repertory of forms was drawn from America’s brand of natural architecture, the log cabin. It was a form of construction that both made sense in practical terms and had the right connotations; it became especially popular for camps in the Adirondacks, and other mountain districts.

By the early 1900s there were local and individual variations, but a brotherhood of plan, materials, motifs, and descriptive language united holiday houses and camps in wild country all over North America. "The outside will weather to natures gray, which, combined with the natural effect of the porch and the rough stonework will cause the building to blend into the landscape." The description (from W. T. Comstock’s Bungalows, Camps and Mountain Houses, 1908) is of a holiday house on the St. Lawrence River, but similar descriptions were being applied to Adirondack camps, or weekend cottages on Signal Mountain in Tennessee. Boulders or rough-hewn stonework were de rigueur for fireplaces as well as foundations and chimneystacks, especially for the great stone fireplace that invariably dominated the living room. Walls were normally of timber, either shingle-clad or of exposed logs, carrying the mark of the adze or sometimes with the bark left on them…