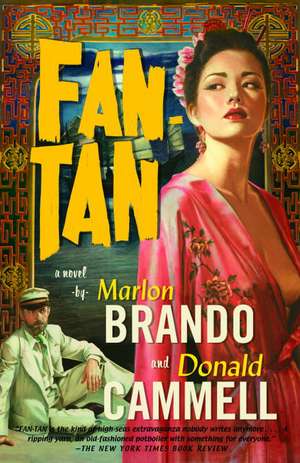

Fan-Tan

Autor Marlon Brando, Donald Cammell Editat de David Thomsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006

Preț: 75.44 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 113

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.44€ • 14.91$ • 12.02£

14.44€ • 14.91$ • 12.02£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096268

ISBN-10: 140009626X

Pagini: 249

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 140009626X

Pagini: 249

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 14 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Marlon Brando appeared in more than forty films, including The Wild One, A Streetcar Named Desire, and Apocalypse Now, and won Academy Awards for his performances in On the Waterfront and The Godfather. His autobiography, Songs My Mother Taught Me, was published in 1994.

Donald Cammell, writer, actor, producer, and director, was best known for his films Performance, Demon Seed, and Wild Side.

From the Hardcover edition.

Donald Cammell, writer, actor, producer, and director, was best known for his films Performance, Demon Seed, and Wild Side.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Prison

Under a black cloud, the prison. And within the prison, a bright rebel. The walls were extremely high, and although this was not possible, they appeared to lean inward yet also to bulge outward, and they were topped with a luminous frosting of broken glass. Seen from the heights of the modest hill named Victoria Peak—from the summer residence of the governor of the Crown Colony of Hong Kong—the prison must have looked very fine. “If the sun were ever to shine,” said Annie to the Portuguee, “the glass would probably glitter. It would look like a necklace of diamonds, Lorenzo. Or a big margarita, in a square cup.”

The sun had not shone since November. This was March 2nd, “In the year of Their Lord” (Annie’s words again) 1927. The vast cloud, several hundreds of miles in diameter and near as thick, squatted upon the unprepossessing island and pissed upon its prison. Annie Doultry (named Anatole for Monsieur France, the novelist) was negotiating the one hundred and eightieth day of a six-month stretch. Born in Edinburgh in the year 1876, he looked his age, every passing minute of it.

His father had been a typesetter, a romantically inclined Scotsman whose hands played with words, a man who loved puns and tragedy, King Lear and Edward Lear. His mother was an unusual woman, lovely and liked, but not quite respectable. She was a MacPherson, but she had a flighty side. She had had lovers, the way some families have pets. Though raised in logic, common sense, and strict economy, once in a while she took absurd gambles—for one, her husband. Later the Doultrys emigrated to Seattle, the boy and the paternal grandmother in tow like many a Midlothian family in those days (when at least there was somewhere to emigrate to). The whole story was vague, though, and Annie was not much given to reflection upon his childhood. His memory was a mess, as full of giant holes as an old sock. Scotland was an accent he loved.

On the other hand, he thought a lot about the future. “That is one of my characteristics, Lorenzo,” he said firmly to the bum of a Portuguee who occupied the bunk above, all aswamp in his own noisome reflections. Annie spoke out like that as a matter of principle, as a way of resisting the danger of thinking silently about one’s own thoughts. That could lead to more thinking and so forth in a potentially hazardous spiral of regressions, the sort of thing one had to be careful of in Victoria Gaol. Men went mad there.

“If you think like a prisoner,” said Lorenzo, “you are a prisoner for life.”

“Not me,” said Annie Doultry.

“But you are here,” said the Portuguee—and it was undeniable. The loose Annie, liberty-loving, unpredictable, spontaneous, was as confined as anyone else in the prison.

“Soon you be old, man,” mocked Lorenzo. “People grow old fast here.”

That warning sank in. It helped explain Annie’s thoughtful look. Once in prison was once too often. Annie Doultry had had little time to ask himself, “Where are you in life? Are you going to be a jailbird or are you going to be your own man?” He had taken that latter hope for granted, but he was too old to be lingering. You could say that it was prison that turned him into a full-blooded fatalist—and made him dangerous.

The grown man himself had a nose bent a little to the left. This is what he had written in pencil under March 1, his yesterday: “They say follow your nose. If I followed mine I guess I would be a Bolshie. But mine is a nose that knows who is boss.” There, his own words hint at it: at a level above mere punnery the nose stood upon its battered cartilage as a sort of memorial to the mockery of the name that might have graced a fair highland woman. “Annie Doultry, rhymes with ‘poultry,’ ” he repeated a number of times, testing his earplugs of candle wax as he screwed them in. Nothing wrong with the ears, their lobes pendulous in the style that indicated wisdom according to the Chinese, but the main organs compactly fitted beneath the hinges of a lantern jaw notorious for its insensitivity. “A face to sink a thousand ships,” said Annie sonorously, as a final trial, and with the satisfaction of one who could no longer hear himself except as cello notes in his own bones.

To turn from the inner life of the man to his three-dimensional situation: the lower bunk of a cell in D block, seven feet by five with the usual grim appurtenances, shit pail and ignoble window, glassless but thickly barred, its sill over five feet from the concrete floor, making it fiendishly difficult for a Chinese to see out. Not so hard for Annie Doultry, however, for he was a large man and terribly thick of thew. Thick-chested, thick thumbs and eyebrows, thick tendons of the wrist and below the kneecap and at the insertion of the hamstring, a valuable asset for a violent man a little past the years of youthful resilience when being thrown out of bars and down companion ladders were just laughable excursions. Thick-bearded he was, too. They had tried to make him shave it off, but he had fought a moral battle with them, from barber to chief warder to the governor himself—and won it. So they had taken his hair but left him his beard to play with. Subsequently each hair had grown prouder, though admittedly grayer. It was an unusual gray, with the cuprite tinge that bronze develops when it takes what the imperial metal workers called the water patina.

Annie had often looked at himself in his mirror—before he lost it. It was a metal mirror, not of great antiquity. It was stainless steel, with a hole to hang it from, four inches square and probably Pittsburgh-made, for trading with Polynesian natives. The mirror was both kind and perceptive, like a rare friend. It stressed equally the deceptive youth and petulance of Doultry’s mouth and the inexpressible, faltering beauty of his eyes. Faltering, because they never quite looked back at themselves, in that or any other mirror. The eyes were guarded because he did not wish them to expose him in any way. Beautiful, by way of his mother presumably, for his father was an ugly fellow; or perhaps just by way of contrast with the rustic ruin of the nose.

His hair was not so thick, of course, and it was cropped repulsively short back and sides. This style was all the rage in the prison, for it denied living space to the poor overcrowded lice.

The next thing was to get his socks in his hands in the correct manner. The heels should fit one in t’other, hand heel in sock heel; but the latter were giant vacuities, and the light was poor. The task had to be done. Nothing else guarded against the roaches.

The Portuguee was moaning, which meant that he was asleep. No earplug was proof against that sound. “He is in the fearful presence of a Jesuitical dream,” said Annie softly. He wished he could write this down in his schoolbook, but the socks made it impossible. “Or perhaps he is praying.” Damnation was what the man wished to avoid at all costs; he had told Annie so. But what made his moans all the more impressive was their coincidental harmonic precision with a Chinese type of moan, straight from the throat in E-flat and out through a mouth agape and then the open window of the hospital ward. This pit of suffering was on the ground floor of A block, just across the alley. The one who moaned had been flogged two or three days ago; his wounds were ulcerating and so on. But it must be made clear that the problem for Annie was not emotional or spiritual: it was a sleeping problem, for the buildings were all crammed together and the acoustics were excellent.

Annie lay back with the socks on his hands. On the great hairy pampas of his chest stood a ravaged tea mug, its blue enamel all mottled with dark perfusions like aging internal bruises promising worse to come. Yet Annie treasured it, for it was his one remaining possession inside this tomb of a prison. The other things—the lighter without a flint, the metal mirror, the brass buckle with the camel’s head—he had gambled away at the roach races. Besides, Annie liked his tea, and Corporal Strachan (Ret.), chief warder of D block, would slip him an extra in this mug, Annie’s own. Now, however, it was empty as an unrewarded sin. On either side of it lay his big bunched mitts, gray as stone, manos de piedra indeed, whose knuckles were protuberant but the fingers astonishingly delicate considering what they had been through—no pun intended.

He remained still. Around his tea mug, his chest was decorated with dried pellets of sorghum (a sort of mealy stuff) flavored with ginger. This was a taste much favored by cockroaches. His broad belly carried a trail of these pellets past his navel via the folds of his filthy canvas pants down to his bare feet. The big toes rested with a look of weary dignity on the rusted bedstead. Along it was laid an enticing line of roach bait, like the fuse to a keg of TNT.

Annie Doultry was lying in wait for his prey with all the punctilious preparation of a hunter of tigers, or of leopards, using his own person in lieu of the tethered goat. For this was the essential feature of his plan: his personal attractiveness to the animals in question. If there is one dish a Chinese roach prefers to sorghum and ginger, it is the dried skin of a whitee’s feet. They would not dream of devouring the living epidermis, they were not looking for trouble, but they favored calluses as an epicurean rabbi does smoked herring. To hold it against them—the roaches, that is—would be rank prejudice; but the fact was that a vulnerable foot was denuded of its natural protection. Feet became little engines of sensitivity. In Annie’s case it was worse, for the roaches nibbled his fingers too throughout the torpid watches of the night—oh, how delicately they chomped away at the husks of his fingertips! Never did they wake him, and circumspection was their motto. No doubt the fearful size of the man gave them pause. “Do not wake him,” they whispered one to another as they satisfied their desire. Hence the socks on his hands.

In a mood of stillness, Annie Doultry waited. The light became dimmer, the black cloud thickening with the approaching night. Under the black cloud, the prison.

Doultry’s cell was no different in shape or size from the other three hundred and twelve. But in status it was one of a select few, like an ancient and appalling Russian railway carriage with First Class all in gold letters on its side. The top-floor view included the top strata of Victoria Peak and the governor’s summer residence, its Union Jack weighted in the moist atmosphere like a proud dishcloth. The grub was better too—pork twice a week, which was twice as much pork as the others got, the others being Chinese, a smaller race and less needful of meat, according to colonial doctrine. (And who will say they were wrong? Too much pork rots the colon’s underwear and the upholstery of the beating heart.)

The top floor of D block was called the E section, which need not confuse the student if he remembers that the E stood for Europe, or European. The exalted E loomed on brooding signs and likewise on Annie Doultry’s institutional garments, stenciled on the canvas in blood-clot red above the broad arrow. The arrow pointed at the letter with pride or with accusation, depending on how you looked at it. In Annie’s case it was also with indignation, for he was an American, a true-blue American since the age of five or thereabouts (though in his heart’s heart he knew he was ever a Celt from the land of mists, and a wanderer).

Doultry was not the first Yank to wear the big E. As the superintendent had patiently explained to him, the E referred not to geography but to race, and in the view of the prison service a white or whitish American was indisputably an E. There were five- hundred-odd A’s and fourteen E’s in residence in March of ’27, including remand prisoners awaiting trial. This proportional representation was surprisingly close to that of the colony as a whole. This again could be regarded as praiseworthy, pointing at the proud blindness of British justice, or as shameful, for obvious reasons.

From the Hardcover edition.

Under a black cloud, the prison. And within the prison, a bright rebel. The walls were extremely high, and although this was not possible, they appeared to lean inward yet also to bulge outward, and they were topped with a luminous frosting of broken glass. Seen from the heights of the modest hill named Victoria Peak—from the summer residence of the governor of the Crown Colony of Hong Kong—the prison must have looked very fine. “If the sun were ever to shine,” said Annie to the Portuguee, “the glass would probably glitter. It would look like a necklace of diamonds, Lorenzo. Or a big margarita, in a square cup.”

The sun had not shone since November. This was March 2nd, “In the year of Their Lord” (Annie’s words again) 1927. The vast cloud, several hundreds of miles in diameter and near as thick, squatted upon the unprepossessing island and pissed upon its prison. Annie Doultry (named Anatole for Monsieur France, the novelist) was negotiating the one hundred and eightieth day of a six-month stretch. Born in Edinburgh in the year 1876, he looked his age, every passing minute of it.

His father had been a typesetter, a romantically inclined Scotsman whose hands played with words, a man who loved puns and tragedy, King Lear and Edward Lear. His mother was an unusual woman, lovely and liked, but not quite respectable. She was a MacPherson, but she had a flighty side. She had had lovers, the way some families have pets. Though raised in logic, common sense, and strict economy, once in a while she took absurd gambles—for one, her husband. Later the Doultrys emigrated to Seattle, the boy and the paternal grandmother in tow like many a Midlothian family in those days (when at least there was somewhere to emigrate to). The whole story was vague, though, and Annie was not much given to reflection upon his childhood. His memory was a mess, as full of giant holes as an old sock. Scotland was an accent he loved.

On the other hand, he thought a lot about the future. “That is one of my characteristics, Lorenzo,” he said firmly to the bum of a Portuguee who occupied the bunk above, all aswamp in his own noisome reflections. Annie spoke out like that as a matter of principle, as a way of resisting the danger of thinking silently about one’s own thoughts. That could lead to more thinking and so forth in a potentially hazardous spiral of regressions, the sort of thing one had to be careful of in Victoria Gaol. Men went mad there.

“If you think like a prisoner,” said Lorenzo, “you are a prisoner for life.”

“Not me,” said Annie Doultry.

“But you are here,” said the Portuguee—and it was undeniable. The loose Annie, liberty-loving, unpredictable, spontaneous, was as confined as anyone else in the prison.

“Soon you be old, man,” mocked Lorenzo. “People grow old fast here.”

That warning sank in. It helped explain Annie’s thoughtful look. Once in prison was once too often. Annie Doultry had had little time to ask himself, “Where are you in life? Are you going to be a jailbird or are you going to be your own man?” He had taken that latter hope for granted, but he was too old to be lingering. You could say that it was prison that turned him into a full-blooded fatalist—and made him dangerous.

The grown man himself had a nose bent a little to the left. This is what he had written in pencil under March 1, his yesterday: “They say follow your nose. If I followed mine I guess I would be a Bolshie. But mine is a nose that knows who is boss.” There, his own words hint at it: at a level above mere punnery the nose stood upon its battered cartilage as a sort of memorial to the mockery of the name that might have graced a fair highland woman. “Annie Doultry, rhymes with ‘poultry,’ ” he repeated a number of times, testing his earplugs of candle wax as he screwed them in. Nothing wrong with the ears, their lobes pendulous in the style that indicated wisdom according to the Chinese, but the main organs compactly fitted beneath the hinges of a lantern jaw notorious for its insensitivity. “A face to sink a thousand ships,” said Annie sonorously, as a final trial, and with the satisfaction of one who could no longer hear himself except as cello notes in his own bones.

To turn from the inner life of the man to his three-dimensional situation: the lower bunk of a cell in D block, seven feet by five with the usual grim appurtenances, shit pail and ignoble window, glassless but thickly barred, its sill over five feet from the concrete floor, making it fiendishly difficult for a Chinese to see out. Not so hard for Annie Doultry, however, for he was a large man and terribly thick of thew. Thick-chested, thick thumbs and eyebrows, thick tendons of the wrist and below the kneecap and at the insertion of the hamstring, a valuable asset for a violent man a little past the years of youthful resilience when being thrown out of bars and down companion ladders were just laughable excursions. Thick-bearded he was, too. They had tried to make him shave it off, but he had fought a moral battle with them, from barber to chief warder to the governor himself—and won it. So they had taken his hair but left him his beard to play with. Subsequently each hair had grown prouder, though admittedly grayer. It was an unusual gray, with the cuprite tinge that bronze develops when it takes what the imperial metal workers called the water patina.

Annie had often looked at himself in his mirror—before he lost it. It was a metal mirror, not of great antiquity. It was stainless steel, with a hole to hang it from, four inches square and probably Pittsburgh-made, for trading with Polynesian natives. The mirror was both kind and perceptive, like a rare friend. It stressed equally the deceptive youth and petulance of Doultry’s mouth and the inexpressible, faltering beauty of his eyes. Faltering, because they never quite looked back at themselves, in that or any other mirror. The eyes were guarded because he did not wish them to expose him in any way. Beautiful, by way of his mother presumably, for his father was an ugly fellow; or perhaps just by way of contrast with the rustic ruin of the nose.

His hair was not so thick, of course, and it was cropped repulsively short back and sides. This style was all the rage in the prison, for it denied living space to the poor overcrowded lice.

The next thing was to get his socks in his hands in the correct manner. The heels should fit one in t’other, hand heel in sock heel; but the latter were giant vacuities, and the light was poor. The task had to be done. Nothing else guarded against the roaches.

The Portuguee was moaning, which meant that he was asleep. No earplug was proof against that sound. “He is in the fearful presence of a Jesuitical dream,” said Annie softly. He wished he could write this down in his schoolbook, but the socks made it impossible. “Or perhaps he is praying.” Damnation was what the man wished to avoid at all costs; he had told Annie so. But what made his moans all the more impressive was their coincidental harmonic precision with a Chinese type of moan, straight from the throat in E-flat and out through a mouth agape and then the open window of the hospital ward. This pit of suffering was on the ground floor of A block, just across the alley. The one who moaned had been flogged two or three days ago; his wounds were ulcerating and so on. But it must be made clear that the problem for Annie was not emotional or spiritual: it was a sleeping problem, for the buildings were all crammed together and the acoustics were excellent.

Annie lay back with the socks on his hands. On the great hairy pampas of his chest stood a ravaged tea mug, its blue enamel all mottled with dark perfusions like aging internal bruises promising worse to come. Yet Annie treasured it, for it was his one remaining possession inside this tomb of a prison. The other things—the lighter without a flint, the metal mirror, the brass buckle with the camel’s head—he had gambled away at the roach races. Besides, Annie liked his tea, and Corporal Strachan (Ret.), chief warder of D block, would slip him an extra in this mug, Annie’s own. Now, however, it was empty as an unrewarded sin. On either side of it lay his big bunched mitts, gray as stone, manos de piedra indeed, whose knuckles were protuberant but the fingers astonishingly delicate considering what they had been through—no pun intended.

He remained still. Around his tea mug, his chest was decorated with dried pellets of sorghum (a sort of mealy stuff) flavored with ginger. This was a taste much favored by cockroaches. His broad belly carried a trail of these pellets past his navel via the folds of his filthy canvas pants down to his bare feet. The big toes rested with a look of weary dignity on the rusted bedstead. Along it was laid an enticing line of roach bait, like the fuse to a keg of TNT.

Annie Doultry was lying in wait for his prey with all the punctilious preparation of a hunter of tigers, or of leopards, using his own person in lieu of the tethered goat. For this was the essential feature of his plan: his personal attractiveness to the animals in question. If there is one dish a Chinese roach prefers to sorghum and ginger, it is the dried skin of a whitee’s feet. They would not dream of devouring the living epidermis, they were not looking for trouble, but they favored calluses as an epicurean rabbi does smoked herring. To hold it against them—the roaches, that is—would be rank prejudice; but the fact was that a vulnerable foot was denuded of its natural protection. Feet became little engines of sensitivity. In Annie’s case it was worse, for the roaches nibbled his fingers too throughout the torpid watches of the night—oh, how delicately they chomped away at the husks of his fingertips! Never did they wake him, and circumspection was their motto. No doubt the fearful size of the man gave them pause. “Do not wake him,” they whispered one to another as they satisfied their desire. Hence the socks on his hands.

In a mood of stillness, Annie Doultry waited. The light became dimmer, the black cloud thickening with the approaching night. Under the black cloud, the prison.

Doultry’s cell was no different in shape or size from the other three hundred and twelve. But in status it was one of a select few, like an ancient and appalling Russian railway carriage with First Class all in gold letters on its side. The top-floor view included the top strata of Victoria Peak and the governor’s summer residence, its Union Jack weighted in the moist atmosphere like a proud dishcloth. The grub was better too—pork twice a week, which was twice as much pork as the others got, the others being Chinese, a smaller race and less needful of meat, according to colonial doctrine. (And who will say they were wrong? Too much pork rots the colon’s underwear and the upholstery of the beating heart.)

The top floor of D block was called the E section, which need not confuse the student if he remembers that the E stood for Europe, or European. The exalted E loomed on brooding signs and likewise on Annie Doultry’s institutional garments, stenciled on the canvas in blood-clot red above the broad arrow. The arrow pointed at the letter with pride or with accusation, depending on how you looked at it. In Annie’s case it was also with indignation, for he was an American, a true-blue American since the age of five or thereabouts (though in his heart’s heart he knew he was ever a Celt from the land of mists, and a wanderer).

Doultry was not the first Yank to wear the big E. As the superintendent had patiently explained to him, the E referred not to geography but to race, and in the view of the prison service a white or whitish American was indisputably an E. There were five- hundred-odd A’s and fourteen E’s in residence in March of ’27, including remand prisoners awaiting trial. This proportional representation was surprisingly close to that of the colony as a whole. This again could be regarded as praiseworthy, pointing at the proud blindness of British justice, or as shameful, for obvious reasons.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Fan-Tan is the kind of high-seas extravaganza nobody writes anymore . . . . A ripping yarn, an old-fashioned potboiler with something for everyone.” –The New York Times Book Review

“An exceedingly strange, high-stepping, low-stooping tale.” –The Washington Post Book World

“Fan-Tan is indeed an outrageous sea-story, with babes and pirates, drink and sex. It has an undeniable charm. . . . Students of film, lovers of Brando, or those with a hankering for another tale of avarice and deceit on the high seas will want to have a look.” –The Houston Chronicle

“An exceedingly strange, high-stepping, low-stooping tale.” –The Washington Post Book World

“Fan-Tan is indeed an outrageous sea-story, with babes and pirates, drink and sex. It has an undeniable charm. . . . Students of film, lovers of Brando, or those with a hankering for another tale of avarice and deceit on the high seas will want to have a look.” –The Houston Chronicle