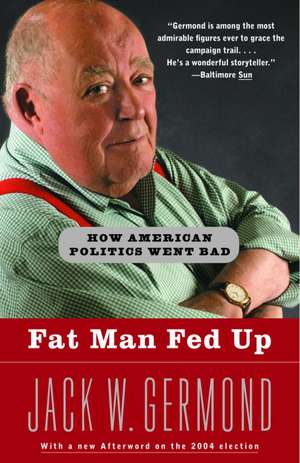

Fat Man Fed Up: How American Politics Went Bad

Autor Jack W. Germonden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2005

Is there any connection between what happens in campaigns and what happens in government? And if not, where does the blame for the discontent lie? Was Tocqueville right? Do we get the leaders we deserve? Indeed, according to Germond, the politicians aren’t the only ones to blame, or even the chief culprits. He describes how he and his colleagues in the news media have been guilty of dumbing-down the political process–and how the voters are too apathetic to demand better coverage and better results. Instead, they simply turn away and too often end up enduring third-rate presidents.

This no-sacred-cows manifesto faces the problems many are reluctant to address:

• Polls and how they are used and abused by politicians and press to mislead gullible voters.

• The critical failure of the press to accurately portray figures in the political realm, from Eugene McCarthy to Barbara Bush to Al Sharpton.

• How the complaints about liberal bias in the press miss the real point: whether that bias, if it exists, colors the way editors and reporters work.

• The staggering influence of television, and the networks’ inability to provide anything but the most simplistic coverage of politics.

• The “big lie” school of campaigning. From “Where’s the beef?” to “compassionate conservatism,” the politics of empty slogans has always placed noise above nuance: Say anything loudly enough and long enough, and voters are bound to mistake it for the truth.

Along the way, Germond illustrates his arguments by drawing from his war chest of priceless anecdotes from decades in the business. With his inimitable combination of incisive journalism and sardonic and witty straight talk, Germond guides us through the fog created by candidates and the media. In this timely, outrageous, and compulsively readable book, no one is let off the hook. Fat Man Fed Up is a bracing look at how we never seem to get the truth about the people we’re electing.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 84.57 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.18€ • 16.72$ • 13.47£

16.18€ • 16.72$ • 13.47£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-18 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812970920

ISBN-10: 0812970926

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

ISBN-10: 0812970926

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.19 kg

Editura: Random House Trade

Notă biografică

JACK GERMOND has been a political columnist for the Baltimore Sun, the Gannett bureau chief in Washington, and a columnist and editor for the late Washington Star. He first appeared on Meet the Press in 1972 and has been a regular on the Today show, CNN, and The McLaughlin Group. He now serves as a panelist on Inside Washington and writes occasional newspaper pieces. He lives in Charles Town, West Virginia.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

In Defense of Politicians

When I was a young reporter covering city hall for the Evening News in Monroe, Michigan, the publisher suggested one day that I should write an occasional editorial on local issues. Fired with the self-righteous certitude of youth, I leaped at the chance. I would straighten out those hacks on the city commission whose meetings I was obliged to cover every Monday night.

But the publisher, a wise man named JS Gray, cautioned me to be patient. "Don't nip at their heels," he said. "We get about what we deserve"-meaning that the quality of the city government reflected the seriousness with which the voters of Monroe considered their decisions when choosing commissioners. We had the proprietor of a small dry-goods store, a salesman in a haberdashery, the operator of a service station, and a couple of young lawyers on the hustle. They were all nice enough people, but we didn't have the municipal equivalent of Robert Taft or Sam Rayburn. So, by JS Gray's reckoning, we shouldn't expect too much.

He was right. Today, after fifty years of exposure to thousands of politicians, I am convinced that we get about what we deserve at all levels of government, up to and including the White House. These days, because so many Americans-almost half-don't bother to vote even in presidential elections, they deserve choices like the one they were offered in 2000, between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Because so few Americans understand the political process or bother to follow it with even a modicum of attention, we elect presidents as empty as George H. W. Bush or as self-absorbed as Bill Clinton-only to be followed by a choice between a Republican obviously over his head and a Democrat too unsure of his own persona to be convincing.

As a group, it turns out, politicians are just like everyone else in our society-a few men and women of high quality, many of different levels of mediocrity, and, finally, a few knaves and poltroons. There are members of Congress who would be overpaid at ten thousand dollars a year and others who would be underpaid at a half million. Nor are presidents of the United States men of some extra dimension, a phrase favored by Richard M. Nixon, other than perhaps the tenacious ambition required to win the office. On the contrary, our presidents are, perhaps too often, very ordinary people.

It is also clear, however, that politicians, whatever their failings, are better people than they are depicted to be in much of the news media and reputed to be in the popular wisdom.

They are men and women who have the nerve to put themselves out there for a popular verdict on their performance and potential delivered in the most public way. Spend an election night with a candidate and you cannot help but be impressed by how wrenching the process can be even for one who is winning. Sure, I'm getting 60 percent of the vote, the candidate mutters to himself, but what about that other 40 percent? Where did I go wrong with them? What can I do to get them next time? They always hope to pitch a shutout.

Many politicians can be good company. They have topics beyond the price of real estate on which they are knowledgeable and interesting. Moreover, they usually have objective minds despite the partisan nature of their work. Often they show, offstage at least, a wicked sense of humor. But they are frequently the victims of grossly inaccurate perceptions.

Contrary to widespread suspicions, for example, they are not in politics for the money. There are exceptions, of course-a few politicians so grasping and perhaps arrogant that they cannot resist the "good things" put in their way by those who want something. They leap at the hot stocks or real estate deals or commodities futures that suddenly appear once they attain power and a position to reward their friends. But most of those who succeed in politics even to the modest level of a seat in the House of Representatives could make a lot more money elsewhere.

Politicians are not hard to read. Their goal is influence rather than money. Wherever they are, they want to take the next step up the ladder. While shaving, the city councilman muses about a seat in the state legislature, where his thoughts quickly turn to Congress, and who knows where that might lead? Ask a candidate for president where he got the idea to run in the first place, and he will usually confess that it came from observing the other candidates and the guy who's already in office.

When I visited Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia for a catfish dinner in Atlanta in 1974, I asked him where he ever got the idea he could be president. "From getting to know the rest of them," he replied, "when they come here to visit." When I encountered one of "the rest of them," Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, a few months later and asked him the same question, his reply was almost identical.

I also remember calling on Senator Ernest Hollings in 1983 after hearing he was quietly raising some political money back home in South Carolina. When I confronted him with my suspicion that he was "thinking about running for president," he replied in that rich South Carolina drawl, "Jack, all senators think about it all the time."

We'll never know how many young politicians there are like Bill Clinton, who had his eye already fixed on the White House when I met him as a thirty-year-old state attorney general running for governor of Arkansas in 1978. But they are not hard to find. For years I made reporting stops in several states a year to meet a local hot property someone had told me enjoyed great potential in national politics-a lieutenant governor such as Mark Hogan of Colorado or Ben Barnes of Texas or perhaps a mayor such as Kevin White of Boston or Jerry Cavanagh of Detroit. Just as every small town has a pitcher who can throw his fastball through a wall, every state has a political phenom who seems destined for the majors. The question is always whether he can throw a curveball, too.

The critical point, however, is that politicians usually want the higher office and the influence it offers in order to achieve some purpose beyond money or their own self-aggrandizement. They have goals that voters may or may not applaud but that are nonetheless legitimate ends they might achieve by gaining a voice in public policy. And we should find some comfort in the transparency of their motives, even if we don't agree with, for example, their determination to turn the national parks over to the oil companies.

So why do we think so poorly of them? Why do so many Americans consider the business too "dirty" to claim their attention? And certainly too dirty to participate in themselves. These days, for most Americans the notion of attending a Republican or Democratic meeting in their ward is laughable. Running for precinct chairman is ludicrous. What is a ward anyway? What's a precinct? The days when ward leaders passed out turkeys at Thanksgiving are long gone.

One reason for this popular disdain is, of course, the few politicians who behave so badly they deserve the contempt with which they are regarded. These are the ones who use their positions to enrich themselves and their friends. The ones who will do anything to be elected and once elected will roll over for any lobbyist or special interest. The ones whose performance in office is such an egregious embarrassment that some people actually notice.

A second factor is the rhetoric of so many politicians who make a career out of denigrating their own calling and presenting themselves as the exception who will clean up the whole ugly mess. When Americans spend eight years listening to Ronald Reagan disparage politicians-he loved to carry on about "draining the swamp" in Washington-it should be no surprise that potential voters turn away. Who wants to be a party to something so rotten?

Others in high places devalue the political life by the example they set. What would thoughtful Americans believe to be the lesson, for example, from the two most important appointments President George Herbert Walker Bush ever made?

The first was the choice-twice-of Dan Quayle for vice president. What did that tell us about the value the elder Bush attached to the highest office in the land? The second was his selection of Clarence Thomas for the Supreme Court. What was that all about other than using the appointment of an African American as a way of saying nyah-nyah to the Democrats? What did it tell voters about the importance of the nation's highest court? That it was just another political asset? If we have to live with it for another thirty years, too bad.

Conventional wisdom also holds that we think so badly of politicians because the news media, broadly defined, cedes so much of its voice to a few columnists and the braying jackasses of talk radio and cable television. But anyone with a long memory in politics knows that the conspiracy theorists and dark dissenters have always been with us, suggesting that the Rush Limbaughs of this age have mined an existing population of yahoos rather than creating one from scratch.

This is a bloc-yahoos in my perhaps jaundiced view-substantial enough to be heard but still a minority of Americans. Assailing a proposed pay raise for Congress, for example, Limbaugh has shown he can flood the mailbags and telephone lines of Capitol Hill with angry protests at a time when opinion polls of the electorate at large show voters about evenly divided on the same issue. It is even possible to uncover a plurality of Americans tolerant of an increase when they hear the arguments justifying it. That dichotomy suggests that the Limbaugh audience is not an accurate sample of the electorate as a whole, which should come as no surprise.

When I once suggested this in a television broadcast, Limbaugh accused me of saying that his listeners were not entitled to be heard. His braying set off a barrage of telephone calls to me in Washington and to the editors of my newspaper, the Baltimore Sun, demanding that I be fired, at the least, or better yet, immolated. It was the most emotional reaction I have ever evoked with anything I wrote or said on television.

This assault on my bona fides as a human being went on for a week or two until by chance I showed up at the annual Radio-TV Correspondents Association dinner at a time when Limbaugh was testing a pilot for a television program. A camera crew from that program approached me during the cocktail hour for an interview. I was abashed at the notion but felt I couldn't refuse. As it turned out, it gave me a golden opportunity. When the interviewer asked what I thought of Rush Limbaugh going on television, I replied that I thought it was great because "we need more fat guys on television." As I recall it, I mentioned "fat guys" several times. End of problem.

Whatever their limits, Limbaugh and his imitators have provided some cohesion and coherence to the minority of Americans who like to rant about the folly of liberalism. And the liberals have helped them along by being so stuffy and self-righteous and so easy to skewer. Taken in very small doses, Rush Limbaugh can be funny. Not so John Kenneth Galbraith.

The distrust of politicians is not fostered by the Limbaughs alone, however. It is part of the operating ethic of the mainstream news media to keep a close watch on public officials and the taxpayers' money. And it is a legitimate function when performed responsibly. But too often both newspapers and television-news organizations project a picture of themselves wringing their hands in glee at exposing these crooks in public life.

The broadcast-television networks, today's single most important provider of news, love stories about how "it's your money" (ABC News) that is being wasted in "the fleecing of America" (NBC News). Newspapers win Pulitzer Prizes for exposés of official misconduct. Reporters love to tell one another old war stories about how they exposed some mayor paving his driveway with public asphalt or some sewer commissioner with his hands in the till. But reporters rarely boast of the stories they wrote about honest politicians doing what they were elected to do. In fact, only the best newspapers bother to provide any detail on the workings of government that might lead a few readers to be less hostile to all elected officials.

Local television can be particularly brutal because its political coverage is so unsophisticated-too often little more than some twinkie, male or female, repeating slogans learned from their betters. They do not hesitate to make broad judgments that go well beyond the diligence and skill of their reporting. A typical case involved a state senator from Florida who had spent years in Tallahassee building knowledge and expertise and earning widespread respect from his peers in both parties. There are people like him in every state legislature, as well as in Congress-politicians who are also public officials who take their jobs seriously and devote far more time to them than is required. One year, however, this senator made the mistake of attending the annual meeting of the National Conference of State Legislatures held in that capital of sin, New Orleans. Although he met his responsibilities by attending the conference and going to the business sessions, he made the fatal blunder of driving over to Biloxi at night to gamble in the casinos that line the stretch of the Gulf Coast known as the Redneck Riviera.

What he didn't expect was a camera crew from a hometown TV station that followed him and reported on his high living in glamorous Biloxi when presumably he should have been spending his leisure discussing land-use planning with fellow legislators from Montana. In fact, since no taxpayer money was involved in the side trip to Biloxi, there wasn't a legitimate story there. But the TV crew made it sound like another case of a politician shirking his duties for his own pleasure and profit.

Given everything voters hear and read, their harsh view of public officials is inevitable. Most Americans, unhappily, are too lazy or uninterested to question whether press accounts of malfeasance present a balanced view. When the sainted Ralph Nader revives the mantra of the late George Corley Wallace and insists that there is not a dime's worth of difference between the two major political parties, it sounds sort of sensible. Many voters like the idea of being "independents" who vote "for the man, not the party."

Enough Americans accepted that notion of civic virtue to alter the outcome of the 2000 presidential election, when votes for Nader clearly defeated Al Gore and elected George W. Bush. (The same thing probably happened in 1968, when George Wallace took enough votes from Hubert H. Humphrey to elect Richard M. Nixon.)

From the Hardcover edition.

In Defense of Politicians

When I was a young reporter covering city hall for the Evening News in Monroe, Michigan, the publisher suggested one day that I should write an occasional editorial on local issues. Fired with the self-righteous certitude of youth, I leaped at the chance. I would straighten out those hacks on the city commission whose meetings I was obliged to cover every Monday night.

But the publisher, a wise man named JS Gray, cautioned me to be patient. "Don't nip at their heels," he said. "We get about what we deserve"-meaning that the quality of the city government reflected the seriousness with which the voters of Monroe considered their decisions when choosing commissioners. We had the proprietor of a small dry-goods store, a salesman in a haberdashery, the operator of a service station, and a couple of young lawyers on the hustle. They were all nice enough people, but we didn't have the municipal equivalent of Robert Taft or Sam Rayburn. So, by JS Gray's reckoning, we shouldn't expect too much.

He was right. Today, after fifty years of exposure to thousands of politicians, I am convinced that we get about what we deserve at all levels of government, up to and including the White House. These days, because so many Americans-almost half-don't bother to vote even in presidential elections, they deserve choices like the one they were offered in 2000, between Al Gore and George W. Bush. Because so few Americans understand the political process or bother to follow it with even a modicum of attention, we elect presidents as empty as George H. W. Bush or as self-absorbed as Bill Clinton-only to be followed by a choice between a Republican obviously over his head and a Democrat too unsure of his own persona to be convincing.

As a group, it turns out, politicians are just like everyone else in our society-a few men and women of high quality, many of different levels of mediocrity, and, finally, a few knaves and poltroons. There are members of Congress who would be overpaid at ten thousand dollars a year and others who would be underpaid at a half million. Nor are presidents of the United States men of some extra dimension, a phrase favored by Richard M. Nixon, other than perhaps the tenacious ambition required to win the office. On the contrary, our presidents are, perhaps too often, very ordinary people.

It is also clear, however, that politicians, whatever their failings, are better people than they are depicted to be in much of the news media and reputed to be in the popular wisdom.

They are men and women who have the nerve to put themselves out there for a popular verdict on their performance and potential delivered in the most public way. Spend an election night with a candidate and you cannot help but be impressed by how wrenching the process can be even for one who is winning. Sure, I'm getting 60 percent of the vote, the candidate mutters to himself, but what about that other 40 percent? Where did I go wrong with them? What can I do to get them next time? They always hope to pitch a shutout.

Many politicians can be good company. They have topics beyond the price of real estate on which they are knowledgeable and interesting. Moreover, they usually have objective minds despite the partisan nature of their work. Often they show, offstage at least, a wicked sense of humor. But they are frequently the victims of grossly inaccurate perceptions.

Contrary to widespread suspicions, for example, they are not in politics for the money. There are exceptions, of course-a few politicians so grasping and perhaps arrogant that they cannot resist the "good things" put in their way by those who want something. They leap at the hot stocks or real estate deals or commodities futures that suddenly appear once they attain power and a position to reward their friends. But most of those who succeed in politics even to the modest level of a seat in the House of Representatives could make a lot more money elsewhere.

Politicians are not hard to read. Their goal is influence rather than money. Wherever they are, they want to take the next step up the ladder. While shaving, the city councilman muses about a seat in the state legislature, where his thoughts quickly turn to Congress, and who knows where that might lead? Ask a candidate for president where he got the idea to run in the first place, and he will usually confess that it came from observing the other candidates and the guy who's already in office.

When I visited Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia for a catfish dinner in Atlanta in 1974, I asked him where he ever got the idea he could be president. "From getting to know the rest of them," he replied, "when they come here to visit." When I encountered one of "the rest of them," Senator Lloyd Bentsen of Texas, a few months later and asked him the same question, his reply was almost identical.

I also remember calling on Senator Ernest Hollings in 1983 after hearing he was quietly raising some political money back home in South Carolina. When I confronted him with my suspicion that he was "thinking about running for president," he replied in that rich South Carolina drawl, "Jack, all senators think about it all the time."

We'll never know how many young politicians there are like Bill Clinton, who had his eye already fixed on the White House when I met him as a thirty-year-old state attorney general running for governor of Arkansas in 1978. But they are not hard to find. For years I made reporting stops in several states a year to meet a local hot property someone had told me enjoyed great potential in national politics-a lieutenant governor such as Mark Hogan of Colorado or Ben Barnes of Texas or perhaps a mayor such as Kevin White of Boston or Jerry Cavanagh of Detroit. Just as every small town has a pitcher who can throw his fastball through a wall, every state has a political phenom who seems destined for the majors. The question is always whether he can throw a curveball, too.

The critical point, however, is that politicians usually want the higher office and the influence it offers in order to achieve some purpose beyond money or their own self-aggrandizement. They have goals that voters may or may not applaud but that are nonetheless legitimate ends they might achieve by gaining a voice in public policy. And we should find some comfort in the transparency of their motives, even if we don't agree with, for example, their determination to turn the national parks over to the oil companies.

So why do we think so poorly of them? Why do so many Americans consider the business too "dirty" to claim their attention? And certainly too dirty to participate in themselves. These days, for most Americans the notion of attending a Republican or Democratic meeting in their ward is laughable. Running for precinct chairman is ludicrous. What is a ward anyway? What's a precinct? The days when ward leaders passed out turkeys at Thanksgiving are long gone.

One reason for this popular disdain is, of course, the few politicians who behave so badly they deserve the contempt with which they are regarded. These are the ones who use their positions to enrich themselves and their friends. The ones who will do anything to be elected and once elected will roll over for any lobbyist or special interest. The ones whose performance in office is such an egregious embarrassment that some people actually notice.

A second factor is the rhetoric of so many politicians who make a career out of denigrating their own calling and presenting themselves as the exception who will clean up the whole ugly mess. When Americans spend eight years listening to Ronald Reagan disparage politicians-he loved to carry on about "draining the swamp" in Washington-it should be no surprise that potential voters turn away. Who wants to be a party to something so rotten?

Others in high places devalue the political life by the example they set. What would thoughtful Americans believe to be the lesson, for example, from the two most important appointments President George Herbert Walker Bush ever made?

The first was the choice-twice-of Dan Quayle for vice president. What did that tell us about the value the elder Bush attached to the highest office in the land? The second was his selection of Clarence Thomas for the Supreme Court. What was that all about other than using the appointment of an African American as a way of saying nyah-nyah to the Democrats? What did it tell voters about the importance of the nation's highest court? That it was just another political asset? If we have to live with it for another thirty years, too bad.

Conventional wisdom also holds that we think so badly of politicians because the news media, broadly defined, cedes so much of its voice to a few columnists and the braying jackasses of talk radio and cable television. But anyone with a long memory in politics knows that the conspiracy theorists and dark dissenters have always been with us, suggesting that the Rush Limbaughs of this age have mined an existing population of yahoos rather than creating one from scratch.

This is a bloc-yahoos in my perhaps jaundiced view-substantial enough to be heard but still a minority of Americans. Assailing a proposed pay raise for Congress, for example, Limbaugh has shown he can flood the mailbags and telephone lines of Capitol Hill with angry protests at a time when opinion polls of the electorate at large show voters about evenly divided on the same issue. It is even possible to uncover a plurality of Americans tolerant of an increase when they hear the arguments justifying it. That dichotomy suggests that the Limbaugh audience is not an accurate sample of the electorate as a whole, which should come as no surprise.

When I once suggested this in a television broadcast, Limbaugh accused me of saying that his listeners were not entitled to be heard. His braying set off a barrage of telephone calls to me in Washington and to the editors of my newspaper, the Baltimore Sun, demanding that I be fired, at the least, or better yet, immolated. It was the most emotional reaction I have ever evoked with anything I wrote or said on television.

This assault on my bona fides as a human being went on for a week or two until by chance I showed up at the annual Radio-TV Correspondents Association dinner at a time when Limbaugh was testing a pilot for a television program. A camera crew from that program approached me during the cocktail hour for an interview. I was abashed at the notion but felt I couldn't refuse. As it turned out, it gave me a golden opportunity. When the interviewer asked what I thought of Rush Limbaugh going on television, I replied that I thought it was great because "we need more fat guys on television." As I recall it, I mentioned "fat guys" several times. End of problem.

Whatever their limits, Limbaugh and his imitators have provided some cohesion and coherence to the minority of Americans who like to rant about the folly of liberalism. And the liberals have helped them along by being so stuffy and self-righteous and so easy to skewer. Taken in very small doses, Rush Limbaugh can be funny. Not so John Kenneth Galbraith.

The distrust of politicians is not fostered by the Limbaughs alone, however. It is part of the operating ethic of the mainstream news media to keep a close watch on public officials and the taxpayers' money. And it is a legitimate function when performed responsibly. But too often both newspapers and television-news organizations project a picture of themselves wringing their hands in glee at exposing these crooks in public life.

The broadcast-television networks, today's single most important provider of news, love stories about how "it's your money" (ABC News) that is being wasted in "the fleecing of America" (NBC News). Newspapers win Pulitzer Prizes for exposés of official misconduct. Reporters love to tell one another old war stories about how they exposed some mayor paving his driveway with public asphalt or some sewer commissioner with his hands in the till. But reporters rarely boast of the stories they wrote about honest politicians doing what they were elected to do. In fact, only the best newspapers bother to provide any detail on the workings of government that might lead a few readers to be less hostile to all elected officials.

Local television can be particularly brutal because its political coverage is so unsophisticated-too often little more than some twinkie, male or female, repeating slogans learned from their betters. They do not hesitate to make broad judgments that go well beyond the diligence and skill of their reporting. A typical case involved a state senator from Florida who had spent years in Tallahassee building knowledge and expertise and earning widespread respect from his peers in both parties. There are people like him in every state legislature, as well as in Congress-politicians who are also public officials who take their jobs seriously and devote far more time to them than is required. One year, however, this senator made the mistake of attending the annual meeting of the National Conference of State Legislatures held in that capital of sin, New Orleans. Although he met his responsibilities by attending the conference and going to the business sessions, he made the fatal blunder of driving over to Biloxi at night to gamble in the casinos that line the stretch of the Gulf Coast known as the Redneck Riviera.

What he didn't expect was a camera crew from a hometown TV station that followed him and reported on his high living in glamorous Biloxi when presumably he should have been spending his leisure discussing land-use planning with fellow legislators from Montana. In fact, since no taxpayer money was involved in the side trip to Biloxi, there wasn't a legitimate story there. But the TV crew made it sound like another case of a politician shirking his duties for his own pleasure and profit.

Given everything voters hear and read, their harsh view of public officials is inevitable. Most Americans, unhappily, are too lazy or uninterested to question whether press accounts of malfeasance present a balanced view. When the sainted Ralph Nader revives the mantra of the late George Corley Wallace and insists that there is not a dime's worth of difference between the two major political parties, it sounds sort of sensible. Many voters like the idea of being "independents" who vote "for the man, not the party."

Enough Americans accepted that notion of civic virtue to alter the outcome of the 2000 presidential election, when votes for Nader clearly defeated Al Gore and elected George W. Bush. (The same thing probably happened in 1968, when George Wallace took enough votes from Hubert H. Humphrey to elect Richard M. Nixon.)

From the Hardcover edition.