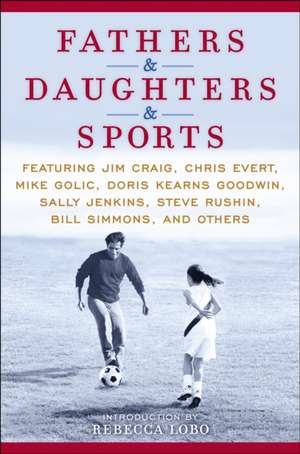

Fathers & Daughters & Sports: Featuring Jim Craig, Chris Evert, Mike Golic, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Sally Jenkins, Steve Rushin, Bill Simmons, and Oth

Chris Evert, Mike Golic, Doris Kearns Goodwinen Limba Engleză Hardback – 30 apr 2010

The evidence fills the covers of this collection of essays by a stellar roster of sports journalists, champion athletes, and celebrated writers. In the Introduction, basketball star Rebecca Lobo recalls how her dad’s advice continued to ring in her ears long after she last played hoops with him on the gravel driveway of their Massachusetts home. Sportswriting legend Dan Shaughnessy celebrates his daughters’ eye-opening softball exploits. Chris Evert recounts how her tennis coach father, Jimmy, taught her coolness under fire. Bill Simmons proudly bequeaths his love of the NBA to his preschool-aged daughter. Doris Kearns Goodwin explains how the not-so-simple act of filling in a scorecard for a father can be an act of love. Mike Veeck, minor-league team owner (and son of baseball’s great impresario, Bill Veeck), writes about the terrifying disease that blinded his daughter, Rebecca, and how they learned from his own father’s example in dealing with disability.

A companion volume to the acclaimed ESPN Books anthology, Fathers & Sons & Sports, Fathers & Daughters & Sports will appeal to everyone who has been either a father or a daughter, or can see himself or herself in these engaging and emotional vignettes. Whether the stories take place on a court, rink, diamond, in the dressage arena, or in the press box, they are universal in appeal, and will touch the hearts of anyone who has ever shot hoops, kicked the ball around, or played catch with a parent or child—and has seen the positive effect these games have on us.

Preț: 120.11 lei

Preț vechi: 144.70 lei

-17% Nou

Puncte Express: 180

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.98€ • 25.07$ • 19.38£

22.98€ • 25.07$ • 19.38£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345520838

ISBN-10: 0345520831

Pagini: 252

Dimensiuni: 146 x 217 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345520831

Pagini: 252

Dimensiuni: 146 x 217 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

Q: Who’s tougher than a former NFL defensive tackle?

A: His daughter. water proof

Mike Golic with Andrew Chaikivsky

When my daughter, Sydney, was ten years old, she told my wife, Chris, and me that she wanted to play lacrosse. She had grown up watching her two older brothers play, and she was eager to try it herself. Great, we told her, and have some fun out there.

She lasted one game. She came off the field, took out her mouthpiece, and vowed never to return.

“This isn’t fun, Dad,” she explained. “I liked watching Mike and Jake play, but the girls’ game is different. They don’t let you hit anybody. You can’t knock people down.” She was visibly disappointed.

Sydney stands tough, no doubt about it. Her brothers now both play Division I football at Notre Dame, and even though they each have a few years on her, young Sydney constantly mixed it up with them. She stood her ground. She fought back. My daughter is a sweet and charming girl, but if you think you can grab the TV remote away from her while she’s watching Viva La Bam, you’re certainly in for some trouble.

But toughness is never simply about physical strength. It’s a mind-set. I’ve been around athletes my whole life—swimming with the local YMCA team as a kid, wrestling in high school and college, playing in the NFL for nine seasons, working at ESPN—and you begin to see in people the direction they’re going to take, how badly they want to succeed and whether or not they have a chance at making it. Very early on, I saw in Sydney something that I had never seen before in someone so young.

She was spending a happy summer swimming and playing soccer when we took a family trip to Notre Dame. Our sons were going for a four-day football camp, and we learned that the athletic department was holding a swimming camp at the same time for girls ages thirteen to eighteen. We had started Sydney with a water-safety course as soon as she was out of the crib, and before long she was picking up strokes like it was second nature. By five, she was competing in swim meets at a country club near our home in Connecticut, and she had been swimming with local teams ever since. But she was only ten years old. Could Sydney attend the Notre Dame camp? we asked. The coaches agreed to let her participate.

We took her to the pool, and I looked over the practice schedule. The distances and sets seemed espe- cially grueling—workouts that would put some football players to shame—and I asked Sydney if she thought she could handle it. She nodded silently, and we kissed her goodbye.

She swam the first session fine, but with the second practice, the distances began to take their toll on her young body. When she climbed out of the pool, I could tell that something was wrong. She looked sad to me, and I asked her if she was okay.

“This is hard, Dad,” she said. “Oh God, this is tough.”

I tried to be encouraging. “The first couple of practices are always the hardest, Sydney. You can do this. You can stick it out.”

I looked at my daughter again and saw tears streaking her cheeks. I felt helpless.

“It’ll be okay,” I said, holding her close in my arms. “We can ask them about easing up on the distances, maybe doing fewer sets.”

She pulled away abruptly. “No,” she said, “I absolutely don’t want to do less.” She wiped her eyes dry. “I’ll be fine.” And with that, she turned around and went back into the pool for the next session.

She finished all her sets that day, every lap for every stroke. She didn’t cry, didn’t come near to getting rattled, never complained. For the first time, I saw an uncommon tenacity in her as she toughed it out for three more days with the other, much older girls. She made it through the entire camp. After the last day’s session, she came back to the hotel room, and it all finally hit her.

She lay down on the bed for a quick nap. She slept for fifteen hours straight.

For a while, Sydney kept up with the soccer, playing goalie for a local travel team. And swimming too. After a very successful soccer season—her team won the state championship—she asked to talk with us about her future. Her future? Sydney was now eleven.

“I can’t play soccer anymore,” she told us. “I want to swim in college, hopefully at Notre Dame, and I want to make the Olympic trials, maybe even get to the Games someday. I know that to do these things I’m going to need to devote all my time to swimming.”

“But we thought you liked soccer?”

“I do like soccer, Dad,” she said. “But I love swimming.”

My wife and I were a little blown away by all this, and we had more than a few discussions about whether or not it was the right thing for her to do. At eleven, she was throwing all her chips into the pot. But I’ll be honest: Part of me was beaming with pride. She knew what she had to do, and she was going for it.

It’s been three years since Sydney’s decision. She’s on her course, progressing steadily through the qualifying times at the regional level, the states, the zones, and the sectionals. Now it’s on to the Junior Nationals, then the Senior Nationals, and then hopefully the Olympic trials in 2012.

She swims six days a week. On Mondays and Fridays, she swims twice, first thing in the morning and then again at night. She also has three dry-land practices each week, two-hour sessions of treadmill work and strength training. Obviously, she goes to high school too and has kept her grade point average above a 3.5. She’s usually done with Friday’s homework by Tuesday night.

She seems to thrive on the routine, but there are days when she’s literally exhausted. She swims between 50,000 and 60,000 yards each week. Thirty miles every six days.

They call swimming a team sport, but it isn’t really. It’s just you and the water and thousands of miles of staring at a thick black line at the bottom of the pool. You’re alone. In practices you just have to keep swimming, working out the calculus of strokes per lap and stroke rate, and executing every turn perfectly. Win a race or set a personal best and the achievement is all yours. If you fail, though, it’s not because the kicker missed a 39-yard field goal. It’s all on you.

And so I worry. My daughter is a beautiful five-foot-ten woman now, but she’s also my youngest child, my little girl, and sometimes I want to grab her, hold her tight, and ask her if she’s okay.

Last spring, we went with Sydney to Maryland for a sectional meet where she would be swimming in six events, from the 100-yard breaststroke to the 400-yard individual medley. Her final race was the 200-yard backstroke, and she swam it strong, finishing in 2:06.46.

It was the first time that she had achieved a qualifying time for the Junior Nationals in any event, the next step in reaching her ultimate goal.

When the race was over, we were all on our feet, clapping and cheering for her as she climbed out of the pool. I looked down and saw the smile on my little girl’s face, the smile of an athlete in triumph, the smile of a beautiful woman.

Mike Golic is co-host of ESPN Radio’s Mike & Mike in the Morning and an analyst for ESPN’s NFL coverage. He cowrote Mike and Mike’s Rules for Sports and Life with his radio partner Mike Greenberg and Andrew Chaikivsky. Golic is a nine-year veteran of the NFL as a defensive tackle and a former captain of the Notre Dame football team.

A: His daughter. water proof

Mike Golic with Andrew Chaikivsky

When my daughter, Sydney, was ten years old, she told my wife, Chris, and me that she wanted to play lacrosse. She had grown up watching her two older brothers play, and she was eager to try it herself. Great, we told her, and have some fun out there.

She lasted one game. She came off the field, took out her mouthpiece, and vowed never to return.

“This isn’t fun, Dad,” she explained. “I liked watching Mike and Jake play, but the girls’ game is different. They don’t let you hit anybody. You can’t knock people down.” She was visibly disappointed.

Sydney stands tough, no doubt about it. Her brothers now both play Division I football at Notre Dame, and even though they each have a few years on her, young Sydney constantly mixed it up with them. She stood her ground. She fought back. My daughter is a sweet and charming girl, but if you think you can grab the TV remote away from her while she’s watching Viva La Bam, you’re certainly in for some trouble.

But toughness is never simply about physical strength. It’s a mind-set. I’ve been around athletes my whole life—swimming with the local YMCA team as a kid, wrestling in high school and college, playing in the NFL for nine seasons, working at ESPN—and you begin to see in people the direction they’re going to take, how badly they want to succeed and whether or not they have a chance at making it. Very early on, I saw in Sydney something that I had never seen before in someone so young.

She was spending a happy summer swimming and playing soccer when we took a family trip to Notre Dame. Our sons were going for a four-day football camp, and we learned that the athletic department was holding a swimming camp at the same time for girls ages thirteen to eighteen. We had started Sydney with a water-safety course as soon as she was out of the crib, and before long she was picking up strokes like it was second nature. By five, she was competing in swim meets at a country club near our home in Connecticut, and she had been swimming with local teams ever since. But she was only ten years old. Could Sydney attend the Notre Dame camp? we asked. The coaches agreed to let her participate.

We took her to the pool, and I looked over the practice schedule. The distances and sets seemed espe- cially grueling—workouts that would put some football players to shame—and I asked Sydney if she thought she could handle it. She nodded silently, and we kissed her goodbye.

She swam the first session fine, but with the second practice, the distances began to take their toll on her young body. When she climbed out of the pool, I could tell that something was wrong. She looked sad to me, and I asked her if she was okay.

“This is hard, Dad,” she said. “Oh God, this is tough.”

I tried to be encouraging. “The first couple of practices are always the hardest, Sydney. You can do this. You can stick it out.”

I looked at my daughter again and saw tears streaking her cheeks. I felt helpless.

“It’ll be okay,” I said, holding her close in my arms. “We can ask them about easing up on the distances, maybe doing fewer sets.”

She pulled away abruptly. “No,” she said, “I absolutely don’t want to do less.” She wiped her eyes dry. “I’ll be fine.” And with that, she turned around and went back into the pool for the next session.

She finished all her sets that day, every lap for every stroke. She didn’t cry, didn’t come near to getting rattled, never complained. For the first time, I saw an uncommon tenacity in her as she toughed it out for three more days with the other, much older girls. She made it through the entire camp. After the last day’s session, she came back to the hotel room, and it all finally hit her.

She lay down on the bed for a quick nap. She slept for fifteen hours straight.

For a while, Sydney kept up with the soccer, playing goalie for a local travel team. And swimming too. After a very successful soccer season—her team won the state championship—she asked to talk with us about her future. Her future? Sydney was now eleven.

“I can’t play soccer anymore,” she told us. “I want to swim in college, hopefully at Notre Dame, and I want to make the Olympic trials, maybe even get to the Games someday. I know that to do these things I’m going to need to devote all my time to swimming.”

“But we thought you liked soccer?”

“I do like soccer, Dad,” she said. “But I love swimming.”

My wife and I were a little blown away by all this, and we had more than a few discussions about whether or not it was the right thing for her to do. At eleven, she was throwing all her chips into the pot. But I’ll be honest: Part of me was beaming with pride. She knew what she had to do, and she was going for it.

It’s been three years since Sydney’s decision. She’s on her course, progressing steadily through the qualifying times at the regional level, the states, the zones, and the sectionals. Now it’s on to the Junior Nationals, then the Senior Nationals, and then hopefully the Olympic trials in 2012.

She swims six days a week. On Mondays and Fridays, she swims twice, first thing in the morning and then again at night. She also has three dry-land practices each week, two-hour sessions of treadmill work and strength training. Obviously, she goes to high school too and has kept her grade point average above a 3.5. She’s usually done with Friday’s homework by Tuesday night.

She seems to thrive on the routine, but there are days when she’s literally exhausted. She swims between 50,000 and 60,000 yards each week. Thirty miles every six days.

They call swimming a team sport, but it isn’t really. It’s just you and the water and thousands of miles of staring at a thick black line at the bottom of the pool. You’re alone. In practices you just have to keep swimming, working out the calculus of strokes per lap and stroke rate, and executing every turn perfectly. Win a race or set a personal best and the achievement is all yours. If you fail, though, it’s not because the kicker missed a 39-yard field goal. It’s all on you.

And so I worry. My daughter is a beautiful five-foot-ten woman now, but she’s also my youngest child, my little girl, and sometimes I want to grab her, hold her tight, and ask her if she’s okay.

Last spring, we went with Sydney to Maryland for a sectional meet where she would be swimming in six events, from the 100-yard breaststroke to the 400-yard individual medley. Her final race was the 200-yard backstroke, and she swam it strong, finishing in 2:06.46.

It was the first time that she had achieved a qualifying time for the Junior Nationals in any event, the next step in reaching her ultimate goal.

When the race was over, we were all on our feet, clapping and cheering for her as she climbed out of the pool. I looked down and saw the smile on my little girl’s face, the smile of an athlete in triumph, the smile of a beautiful woman.

Mike Golic is co-host of ESPN Radio’s Mike & Mike in the Morning and an analyst for ESPN’s NFL coverage. He cowrote Mike and Mike’s Rules for Sports and Life with his radio partner Mike Greenberg and Andrew Chaikivsky. Golic is a nine-year veteran of the NFL as a defensive tackle and a former captain of the Notre Dame football team.

Descriere

A collection of essays by a stellar roster of sports journalists, champion athletes, and celebrated writers. Whether the stories take place on a court, rink, diamond, in the dressage arena, or in the press box, they are universal in appeal, and will touch the hearts of anyone who has ever shot hoops, kicked the ball around, or played catch with a parent or child.

Notă biografică

ESPN; Introduction by Rebecca Lobo