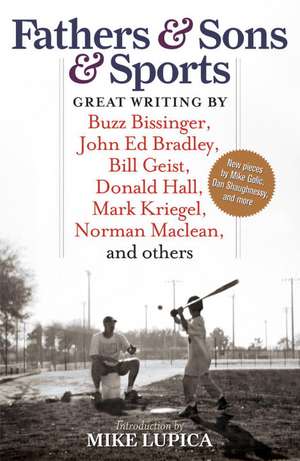

Fathers & Sons & Sports

Autor Buzz Bissinger, John Ed Bradley, Bill Geisten Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2009

Henry Aaron, as told to Cal Fussman • Michael J. Agovino • Buzz Bissinger • Jeff Bradley • John Ed Bradley • James Brown • Darcy Frey • Tom Friend • Bill Geist • Mike Golic • Donald Hall • Paul Hoffman • Mark Kriegel • Norman Maclean • John Buffalo Mailer • Ron Reagan • Peter Richmond • Jeremy Schaap • Lew Schneider • Dan Shaughnessy • Paul Solotaroff • John Jeremiah Sullivan • Wright Thompson • Steve Wulf

The unforgettable accounts here include the stories of a professional football player passing on his father’s secrets to his own sons, a severely disabled boy discovering joy on a surfboard, a wealthy NFL player taking his coddled children back to the mean streets that made him, and a major league manager who must face the hard fact that nothing, not even unconditional love, can save his son.

Anyone who has ever been a father or a son will see himself in these moving snapshots of family life at its most emotional. Whether the stories take place on a diamond, a court, a gridiron, a fairway, or a chessboard, they’re all about the same subject: fatherhood, one of the world’s most intriguing sports.

Preț: 117.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 177

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.54€ • 23.45$ • 18.61£

22.54€ • 23.45$ • 18.61£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781933060705

ISBN-10: 1933060700

Pagini: 319

Dimensiuni: 136 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: ESPN Video

ISBN-10: 1933060700

Pagini: 319

Dimensiuni: 136 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: ESPN Video

Notă biografică

Mike Lupica , a nationally known columnist for the New York Daily News, has written books for both fathers and sons. His first two novels for young readers, Travel Team and Heat, reached # 1 on the New York Times bestseller list. Lupica is also a Sunday morning regular on ESPN’s The Sports Reporters. He lives in New Canaan, Connecticut, with his wife, Taylor, and their four children.

Extras

Introduction

MIKE LUPICA

My dad first took me into the room, welcomed me into the company of sports,when I was six.

He had long since completed all the preliminaries, patiently teaching me the rules of baseball, buying me my first bat and glove, giving me a cut-off five-iron and showing me how to grip it, taking me to the park next door to our house and watching as I finally, and with everything I had, managed to heave a basketball to the rim for the first time.

But it was on the day the Giants played the Colts in 1958– the first sudden-death championship game in NFL history, the one that made pro football a big television attraction in this country–that I joined the conversation.

We lived in upstate New York at the time. There was no American Football League, no DirecTV,no NFL Sunday Ticket, no thought even given to letting people watch any matchup they wanted on Sunday afternoon. For me, there was just one game: The football Giants. And now they had beaten Jim Brown and the Cleveland Browns, and they were going up against Johnny Unitas’s Colts for the title. So this Sunday was different. I wasn’t just watching with my dad. All of my uncles were there as well. Just like that, I was in. So many things have changed for me in the life I’ve been lucky to lead since that day in December 1958, but one thing remains the same: There is no game I am watching that I wouldn’t rather be watching with my dad. The best days I’ve had in sports, either in front of a TV screen or at the ballpark,were shared with my dad and my three sons.

(And just for the record:My nine-year-old daughter? When she occasionally sits with me and asks questions about a game I am watching–usually with her brothers out of the room, usually a baseball game–it is a joy of my life. But this is a book about fathers and sons and sports. I’m just doing my job here!) The first great day was December 28, 1958, Alan Ameche going into the end zone in overtime, sports breaking my heart for the first time.

I remember that play. I remember a big fumble from Frank Gifford. I remember Unitas’s near perfection, never missing a receiver or a throw. The rest of it is a blur.What I know now about the game I have filled in over the years: Raymond Berry’s catches, the big catch Jim Mutscheller made,Lenny Moore’s running, and the plays that Chuckin’ Charlie Conerly made for the Giants. Because it was such an iconic game I have, over time, been able to remember what I had forgotten. ESPN Classic will do that for you.

What I have never forgotten and never will forget is the magic in the room as I sat on the couch next to my father.The excitement of it all.The air in the room.

My friend Seymour Siwoff, who founded the Elias Sports Bureau, once described sports as you talking about a moment and me talking about the same moment and the air in between us. I remember sitting next to my dad and I remember that air. There was no formal announcement, no rite of initiation. It was as if my dad took me by the hand and we entered this world together, the world of shared memories and a shared language and all the things, good and bad, that sports make you feel. The best part of it is,we are still in it.Together.And now my own sons are there with us. I’m sure you have your own home court crowd, the one arena in sports where you most want to be. That is mine.

My oldest boy is in college now, Boston College, my alma mater.My mom and dad live in New Hampshire, in the house we moved into in 1964. The house is less than an hour from downtown Boston, so this past October I arranged for my pop and my son to attend the first two games of the Red Sox-Indians American League Championship Series.

I was going up to Boston for the series’ last two games, so I watched the first two at home. And there was a moment in Game One when the count went to 3-2 on Manny Ramirez and the crowd at Fenway got up, the way it does, and the cameras began to take random shots, the way cameras do. Suddenly there they were.

My son was up first.My dad, who was eighty-three at the time, took a little longer to get out of his seat, though he would tell me later that it was only because his grandson, the college boy, was blocking his way.

There they were, the two of them front and center on my television screen, side by side. There was my son where I had always been, next to my dad.

We had TiVo on the set I was watching, so I was able to record the moment the way you would record a great play, a great shot or catch or swing of the bat. Because this wasn’t a picture worth a thousand words, it was worth a million.Because there it was, the bond between fathers and sons I am trying to explain here as best I can:

That bond being passed on.

This introduction is about my own father-son memories. I’m sure you have your own, about your first bat and glove, about your first trip to the ballpark,Fenway Park or Yankee Stadium or Wrigley or Dodger Stadium. My dear friend Pete Hamill remembers everything–and I mean everything–about the day he went to Ebbets Field with his father, the two of them seeing for the first time Jack Roosevelt Robinson play a game of baseball for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“That was the day the template was cut,” is the way Hamill puts it.

You never need TiVo for a day like that.

Here’s another childhood memory from upstate New York. We lived more than five hours away from Yankee Stadium by car, and so there were years when the only big-league baseball I saw was the old exhibition game they used to play in Cooperstown on Hall of Fame weekend.One year,by sheer blessed chance, the Yankees were in that game.

Only once we were inside the little antique ballpark, it began to rain.And it wouldn’t stop raining.And before long it was endof- the-world rain, and everybody was running back to the streets of the little town, looking for some sort of cover, any sort of cover. Including my dad and me.

We managed to find an awning on Cooperstown’s main street. As we were catching our breath, soaking wet, we turned around.There, in full uniform, standing next to us in his No. 14, was Bill “Moose” Skowron. The ballplayers, it turned out, had come running to town like everybody else.

My dad is a sweet, shy, gentle man. But now he tapped Skowron on the shoulder, introduced himself, and said, “Mr. Skowron, I’d like you to meet my son,Michael.”

The big man shook my hand.

The first big leaguer I ever met.

Another door in sports opened by my dad.

He never pushed them on me.He has always loved sports, has always been passionate about his teams, but never allowed that passion to run wild. Never allowed sports to lose its wonderful place in his wonderful life. If he has passed on anything to me, it is that.

My friend William Goldman,who wrote The Princess Bride and Marathon Man, who won Oscars for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All The President’s Men, is always talking about how he instantly finds a comfort zone in any Hollywood meeting if somebody in the room is a sports fan.

“I know we’ve got a common language,”Bill says.

I got that language from my dad. It isn’t something I remember learning, the way I remember struggling to learn Spanish or French in school.There is no day that I remember my dad sitting me down and telling me he was going to teach me the language of the infield-fly rule.We just started communicating through sports as well as we communicated through anything.

And still do.

When Jack Nicklaus came from behind to win the Masters in 1986,with his son Jackie on the bag that day, I probably called my dad ten times over the last nine holes. It was the year before my first son was born. So when the big things happened in sports, it was still my pop and me.

A year earlier, we had been in his den in New Hampshire when Doug Flutie completed that Hail Mary pass against Miami the day after Thanksgiving, the most famous pass not just in the history of his school and mine, but in all of college football.

Once more, my dad and I were in front of a television, two big kids hugging each other and doing this crazy dance in front of the set, sharing the magic of that moment, breathing in the intoxicating air in the room.

I remember Flutie on the run and the ball in the air and then Flutie sprinting down the field to celebrate with his buddy, Gerard Phelan, the guy who had somehow caught that ball. I see it now and wish I was there.

Not in the Orange Bowl.

But back in the room with my father.

So I hope you enjoy reading about fathers and sons and sports in the pages of this book. I have my memories.The writers of these pieces have their own.

Ron Reagan writes about the first time he beat his father in the swimming pool, a boy of twelve edging out his sixty-year-old dad.Poet Laureate Donald Hall writes lyrically about the simple act of playing catch with your father, and John Buffalo Mailer writes about the morning his famous father,Norman, led him to believe–at the age of three–that he had the best right-hand cross in the world.

John Ed Bradley explains the lessons he learned about football and life from his father the coach, and the great Henry Aaron dreams of making it big in sports. John Jeremiah Sullivan writes about seeking to understand his own deceased sportswriter father by looking into the man’s love of sports, particularly his love for the horse Secretariat.

And pardon my prejudice, but there is a particularly wonderful piece written by my friend Jeremy Schaap about his late father, Dick. Maybe you know this and maybe not, but I was lucky enough to have Dick Schaap as a friend and mentor for more than thirty years of my life, and then lucky enough to sit next to him on ESPN’s The Sports Reporters for more than a decade.

Besides the one next to my dad and my boys, it is the best seat I’ve ever had.

In “A Father’s Gift,” Jeremy writes about how Dick missed two of Reggie Jackson’s three home runs in Game Six of the 1977 World Series because he was off getting hot dogs and sodas for his son.

In “Holy Ground,”Wright Thompson explains the pain of losing his dad to cancer before he could deliver on a promise to share a golf trip to the Masters Tournament with him. These are only a few of the fine pieces in this book. I urge you to read them all. In the end, they will do exactly what sports does. They will make you feel and they will make you remember.

I write young adult novels now, have for years.The first was Travel Team, a book that really began for me–unexpectedly– the first time sports broke the heart of my second son, when he was cut from a seventh-grade travel team for being too small. I started a basketball team that year for all the boys who got cut, and it became one of the greatest sports experiences, one of the greatest seasons, of my life.

My son will remember that season the way all the boys on that team will remember it. But more than a season he didn’t expect to have, one that none of the boys expected to have, it was an adventure my boy and I shared together.

My newest novel, The Big Field, is built around the strained relationship between the hero and his father, a failed ballplayer. The two think the bond between them is irretrievably lost until their common love of sports helps them find the love they still have for each other.

Again: I have my own stories,my own memories, about my dad.You have yours.The writers of these stories have theirs.The language, though, the language doesn’t change. Neither does the air in the room.

Mike Lupica

January 2008

MIKE LUPICA

My dad first took me into the room, welcomed me into the company of sports,when I was six.

He had long since completed all the preliminaries, patiently teaching me the rules of baseball, buying me my first bat and glove, giving me a cut-off five-iron and showing me how to grip it, taking me to the park next door to our house and watching as I finally, and with everything I had, managed to heave a basketball to the rim for the first time.

But it was on the day the Giants played the Colts in 1958– the first sudden-death championship game in NFL history, the one that made pro football a big television attraction in this country–that I joined the conversation.

We lived in upstate New York at the time. There was no American Football League, no DirecTV,no NFL Sunday Ticket, no thought even given to letting people watch any matchup they wanted on Sunday afternoon. For me, there was just one game: The football Giants. And now they had beaten Jim Brown and the Cleveland Browns, and they were going up against Johnny Unitas’s Colts for the title. So this Sunday was different. I wasn’t just watching with my dad. All of my uncles were there as well. Just like that, I was in. So many things have changed for me in the life I’ve been lucky to lead since that day in December 1958, but one thing remains the same: There is no game I am watching that I wouldn’t rather be watching with my dad. The best days I’ve had in sports, either in front of a TV screen or at the ballpark,were shared with my dad and my three sons.

(And just for the record:My nine-year-old daughter? When she occasionally sits with me and asks questions about a game I am watching–usually with her brothers out of the room, usually a baseball game–it is a joy of my life. But this is a book about fathers and sons and sports. I’m just doing my job here!) The first great day was December 28, 1958, Alan Ameche going into the end zone in overtime, sports breaking my heart for the first time.

I remember that play. I remember a big fumble from Frank Gifford. I remember Unitas’s near perfection, never missing a receiver or a throw. The rest of it is a blur.What I know now about the game I have filled in over the years: Raymond Berry’s catches, the big catch Jim Mutscheller made,Lenny Moore’s running, and the plays that Chuckin’ Charlie Conerly made for the Giants. Because it was such an iconic game I have, over time, been able to remember what I had forgotten. ESPN Classic will do that for you.

What I have never forgotten and never will forget is the magic in the room as I sat on the couch next to my father.The excitement of it all.The air in the room.

My friend Seymour Siwoff, who founded the Elias Sports Bureau, once described sports as you talking about a moment and me talking about the same moment and the air in between us. I remember sitting next to my dad and I remember that air. There was no formal announcement, no rite of initiation. It was as if my dad took me by the hand and we entered this world together, the world of shared memories and a shared language and all the things, good and bad, that sports make you feel. The best part of it is,we are still in it.Together.And now my own sons are there with us. I’m sure you have your own home court crowd, the one arena in sports where you most want to be. That is mine.

My oldest boy is in college now, Boston College, my alma mater.My mom and dad live in New Hampshire, in the house we moved into in 1964. The house is less than an hour from downtown Boston, so this past October I arranged for my pop and my son to attend the first two games of the Red Sox-Indians American League Championship Series.

I was going up to Boston for the series’ last two games, so I watched the first two at home. And there was a moment in Game One when the count went to 3-2 on Manny Ramirez and the crowd at Fenway got up, the way it does, and the cameras began to take random shots, the way cameras do. Suddenly there they were.

My son was up first.My dad, who was eighty-three at the time, took a little longer to get out of his seat, though he would tell me later that it was only because his grandson, the college boy, was blocking his way.

There they were, the two of them front and center on my television screen, side by side. There was my son where I had always been, next to my dad.

We had TiVo on the set I was watching, so I was able to record the moment the way you would record a great play, a great shot or catch or swing of the bat. Because this wasn’t a picture worth a thousand words, it was worth a million.Because there it was, the bond between fathers and sons I am trying to explain here as best I can:

That bond being passed on.

This introduction is about my own father-son memories. I’m sure you have your own, about your first bat and glove, about your first trip to the ballpark,Fenway Park or Yankee Stadium or Wrigley or Dodger Stadium. My dear friend Pete Hamill remembers everything–and I mean everything–about the day he went to Ebbets Field with his father, the two of them seeing for the first time Jack Roosevelt Robinson play a game of baseball for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

“That was the day the template was cut,” is the way Hamill puts it.

You never need TiVo for a day like that.

Here’s another childhood memory from upstate New York. We lived more than five hours away from Yankee Stadium by car, and so there were years when the only big-league baseball I saw was the old exhibition game they used to play in Cooperstown on Hall of Fame weekend.One year,by sheer blessed chance, the Yankees were in that game.

Only once we were inside the little antique ballpark, it began to rain.And it wouldn’t stop raining.And before long it was endof- the-world rain, and everybody was running back to the streets of the little town, looking for some sort of cover, any sort of cover. Including my dad and me.

We managed to find an awning on Cooperstown’s main street. As we were catching our breath, soaking wet, we turned around.There, in full uniform, standing next to us in his No. 14, was Bill “Moose” Skowron. The ballplayers, it turned out, had come running to town like everybody else.

My dad is a sweet, shy, gentle man. But now he tapped Skowron on the shoulder, introduced himself, and said, “Mr. Skowron, I’d like you to meet my son,Michael.”

The big man shook my hand.

The first big leaguer I ever met.

Another door in sports opened by my dad.

He never pushed them on me.He has always loved sports, has always been passionate about his teams, but never allowed that passion to run wild. Never allowed sports to lose its wonderful place in his wonderful life. If he has passed on anything to me, it is that.

My friend William Goldman,who wrote The Princess Bride and Marathon Man, who won Oscars for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and All The President’s Men, is always talking about how he instantly finds a comfort zone in any Hollywood meeting if somebody in the room is a sports fan.

“I know we’ve got a common language,”Bill says.

I got that language from my dad. It isn’t something I remember learning, the way I remember struggling to learn Spanish or French in school.There is no day that I remember my dad sitting me down and telling me he was going to teach me the language of the infield-fly rule.We just started communicating through sports as well as we communicated through anything.

And still do.

When Jack Nicklaus came from behind to win the Masters in 1986,with his son Jackie on the bag that day, I probably called my dad ten times over the last nine holes. It was the year before my first son was born. So when the big things happened in sports, it was still my pop and me.

A year earlier, we had been in his den in New Hampshire when Doug Flutie completed that Hail Mary pass against Miami the day after Thanksgiving, the most famous pass not just in the history of his school and mine, but in all of college football.

Once more, my dad and I were in front of a television, two big kids hugging each other and doing this crazy dance in front of the set, sharing the magic of that moment, breathing in the intoxicating air in the room.

I remember Flutie on the run and the ball in the air and then Flutie sprinting down the field to celebrate with his buddy, Gerard Phelan, the guy who had somehow caught that ball. I see it now and wish I was there.

Not in the Orange Bowl.

But back in the room with my father.

So I hope you enjoy reading about fathers and sons and sports in the pages of this book. I have my memories.The writers of these pieces have their own.

Ron Reagan writes about the first time he beat his father in the swimming pool, a boy of twelve edging out his sixty-year-old dad.Poet Laureate Donald Hall writes lyrically about the simple act of playing catch with your father, and John Buffalo Mailer writes about the morning his famous father,Norman, led him to believe–at the age of three–that he had the best right-hand cross in the world.

John Ed Bradley explains the lessons he learned about football and life from his father the coach, and the great Henry Aaron dreams of making it big in sports. John Jeremiah Sullivan writes about seeking to understand his own deceased sportswriter father by looking into the man’s love of sports, particularly his love for the horse Secretariat.

And pardon my prejudice, but there is a particularly wonderful piece written by my friend Jeremy Schaap about his late father, Dick. Maybe you know this and maybe not, but I was lucky enough to have Dick Schaap as a friend and mentor for more than thirty years of my life, and then lucky enough to sit next to him on ESPN’s The Sports Reporters for more than a decade.

Besides the one next to my dad and my boys, it is the best seat I’ve ever had.

In “A Father’s Gift,” Jeremy writes about how Dick missed two of Reggie Jackson’s three home runs in Game Six of the 1977 World Series because he was off getting hot dogs and sodas for his son.

In “Holy Ground,”Wright Thompson explains the pain of losing his dad to cancer before he could deliver on a promise to share a golf trip to the Masters Tournament with him. These are only a few of the fine pieces in this book. I urge you to read them all. In the end, they will do exactly what sports does. They will make you feel and they will make you remember.

I write young adult novels now, have for years.The first was Travel Team, a book that really began for me–unexpectedly– the first time sports broke the heart of my second son, when he was cut from a seventh-grade travel team for being too small. I started a basketball team that year for all the boys who got cut, and it became one of the greatest sports experiences, one of the greatest seasons, of my life.

My son will remember that season the way all the boys on that team will remember it. But more than a season he didn’t expect to have, one that none of the boys expected to have, it was an adventure my boy and I shared together.

My newest novel, The Big Field, is built around the strained relationship between the hero and his father, a failed ballplayer. The two think the bond between them is irretrievably lost until their common love of sports helps them find the love they still have for each other.

Again: I have my own stories,my own memories, about my dad.You have yours.The writers of these stories have theirs.The language, though, the language doesn’t change. Neither does the air in the room.

Mike Lupica

January 2008

Descriere

This anthology collects unforgettable tales about fathers and sons who have found a common language in a shared passion--sports.