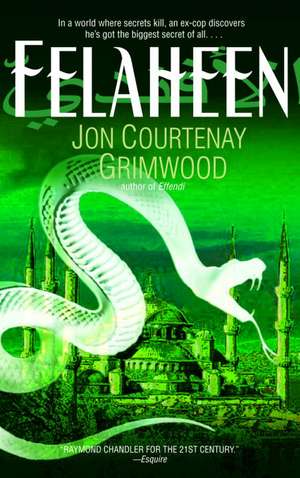

Felaheen: The Third Arabesk

Autor Jon Courtenay Grimwooden Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 noi 2005

Set in a 21st-century Ottoman Empire, Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s acclaimed Arabesk series is a noir action-thriller with an exotic twist. Here an ex-cop with nothing to lose finds himself on the trail of a man he doesn’t believe in: his father.

Ashraf Bey has been a lot of things–and most of them illegal. Now, having resigned as El Iskandryia’s Chief of Detectives, he’s taking stock of his life and there’s not much: a mistress he’s never made love to, a niece everyone thinks is mentally incompetent, and a credit card bill rising towards infinity. With a revolt breaking out across North Africa, the world seems to be racing Raf straight to hell. The last thing he needs is a father he’s never known. But when the old Emir’s security chief requests that Raf come out of retirement to investigate an assassination attempt on His Excellency, that’s exactly what Raf gets. Now, disguised as an itinerant laborer, Raf goes underground to discover a man–and a past–he never knew…and won’t survive again.

“Fast, furious, fun and elegant, the Arabesk trilogy is one of the best things to hit the bookstores in a while.” –SF Revu

“Felaheen is SF at its most inventive.” –Guardian

Preț: 69.70 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 105

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.34€ • 14.50$ • 11.21£

13.34€ • 14.50$ • 11.21£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553383782

ISBN-10: 0553383787

Pagini: 357

Dimensiuni: 144 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Spectra Books

ISBN-10: 0553383787

Pagini: 357

Dimensiuni: 144 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.28 kg

Editura: Spectra Books

Notă biografică

Jon Courtenay Grimwood lives in England. The third book in his acclaimed "Arabesk" series, FELAHEEN, won the 2003 British Science Fiction Association Award, appeared on Locus Magazine's 2003 Recommended Reading List, and appeared on SFSite's Best of 2003 list.

Extras

CHAPTER 1

Tuesday 1st February

"Out of my way." Major Jalal jabbed his elbow into the kidney of one photographer and shouldered another into the gutter, watching as frozen slush filled the man's scruffy shoes. Ten paces at most separated the limo from the door of the casino but five photographers barred the way. Well, three now.

"Chill," his boss said with a broad smile. The major wasn't sure if that was an order or if His Excellency was commenting on New York's weather. So Jalal kept his reply to a nod, which covered both bases.

"Prince . . ."

"Over here . . ."

His Excellency Kashif Pasha was used to catcalls and noise from nasrani paparazzi, who whistled at him like he was someone's dog. It was the only thing he hated about coming to New York.

"Look this way."

Kashif Pasha made the mistake of doing just that and found himself staring into the smirking face of Charlie Vanhie, a WASP reporter he'd had the misfortune to meet at least three times before.

"Tell us about your plan to throw a dinner to celebrate your parents' fiftieth wedding anniversary . . ."

Having made the mistake of looking at Charlie Vanhie, the pasha then compounded his error by actually speaking to the man. "Forty-fifth," he corrected, "it will be their forty-fifth."

"What makes you think the Emir will turn up?"

Kashif Pasha stared at the man.

"Given that he won't even be in the same room as your mother. What was it he called her . . . ?"

Major Jalal began to move towards the speaker but His Excellency held up one hand. "Leave it," he told the major. "Let me handle this."

Around the time Kashif Pasha stood on a snow-covered sidewalk in Manhattan, bathed in the light of a flashgun, a small girl sat at a cheap plastic laptop. She was preparing to answer a long list of EQ questions, most of them multiple choice.

Draped around the girl's neck was a grey kitten worn like a collar. Actually, Ifritah was almost six months old but she still behaved like a kitten so that was how the girl thought of her.

Lady Hana al-Mansur, wrote the girl in a box marked name. Then she deleted it and typed Hani instead. There was also a box for her age but this was more problematic since no one was quite sure. She chose 10, because either she was about to become ten, or she was ten already, in which case she'd be eleven in less than a week.

In the box marked nationality Hani wrote Ottoman and when the software rejected this she wrote it again. So then the computer offered her a long list of alternatives which she rejected, finally compromising on Other.

The room where Hani sat was in a house five thousand five hundred and seven miles from New York. In El Iskandryia. A city on the left-hand edge of the Nile Delta. Right at the top where the delta jutted out into the Mediterranean.

The madersa looked in on itself in that way many North African houses do. It was old and near decrepit in places. With a grand entrance onto Rue Sherrif at the front and an unmarked door that led out to an alley at the rear.

Guarding this door was a porter named Khartoum, because the city of Khartoum was where he came from and he'd refused to reveal any other. He smoked cigars backwards, with the lit end inside his mouth and had given Hani a tiny silver hand on a thread of cotton to help her do well in the tests.

This impressed Hani greatly and it went, almost without saying, that Hani would rather have had Khartoum with her than the cat but her uncle, the bey, had forbidden it. Not crossly. Just firmly. Because the box containing the test stated that all computers were to be off-line and no other people were to be in the room when the test was taken.

First off was an easy question about being caught in a plane crash. With her plane going down would she: 1) scribble her will on the back of an envelope; 2) offer her help to the pilot; 3) continue to read a magazine?

The answer was obviously continue to read since, a) she'd never learned to fly and so offering help was pointless and, b) she was unlikely to be carrying an envelope, had she had anything to leave anybody which she didn't . . .

Next question was about her father/stepfather/legal other. Since Hani had never met the first, lacked the second and was uncertain if her Uncle Ashraf counted as the third, she ignored it, as she did two more questions about her family.

Then there was a section on school friends, which Hani didn't even bother to read. The final bit was the simplest . . . Five hundred faces on a flat screen, each expressing anger or joy, happiness, boredom, sadness or pain.

Her job was to name that emotion. The section started at a crawl and for the first twenty or so faces Hani thought this was as fast as the software could go, but as impatience set in and Hani started hammering at the keys, her screen became a blur and soon the small girl was selecting answers so fast her computer had all its fans running.

She got every expression right except for five benchmark indicators where the picture was of her. Even so, according to the EQ software, Hani's was the highest score ever recorded for that section, certainly within the time.

The IQ test that followed was infinitely more difficult. So difficult in fact that Hani ran out of time on her very first question. Which was the odd animal out--a sheep, a hen, a dog or a shark? Above each choice was the small photograph, just in case she'd forgotten what the animals looked like.

As answers went, the shark seemed much too obvious. Especially given this was an intelligence test and identifying the first three as air-breathing and the shark as a cartilaginous water dweller took no intelligence at all.

So what else could it be? Sheep were actually domesticated goats. At least Hani was pretty sure they were. Hens had also been domesticated, as had dogs, which were really domesticated wolves. So the answer could be shark but for a less obvious reason, because humanity had no history of domesticating sharks.

But what if that was still too obvious?

In the end she chose the sheep over the hen, dog and shark because it was a herbivore and all the others ate meat. Although, in the case of the hen, Hani suspected that the bird was actually omnivorous. This seemed the mostly likely of the nineteen possible answers she jotted onto a piece of scrap paper.

"So what went wrong?" her uncle asked later, when he finally tracked Hani down to the madersa's roof where the girl sat oblivious to a cold glowering sky.

"With what?"

"Your second test. You only did one question and even then . . ." His voice trailed away.

"It wasn't the sheep?"

The thin man with the shades, goatee beard and drop-pearl earring shook his head.

"Which one was it?" Hani demanded.

"The shark."

"Because it's not domesticated?"

Ashraf al-Mansur, known also as Ashraf Bey, put his face in his hands and for a moment looked almost ill. He had a niece half the city thought was retarded. A mistress who wasn't his mistress because they'd never actually fucked. And his own life . . . Raf stopped, considering that point.

He'd recently resigned his job, the madersa cost more to run than he had coming in and yet, between them, Hani and Zara were worth millions. He was being chased for debts while living in a house with two of North Africa's wealthiest people, either of whom would give him the money, if only he'd stop refusing to consider it. As Zara said, getting that to make sense was like trying to fasten jeans with a zip one side and buttonholes the other.

Hani sat her test again next morning. This time on the flat roof of the al-Mansur madersa. And she did exactly what her uncle suggested, which was give the most obvious answer to everything. It took her less than fifteen minutes to achieve a score higher than the software could handle.

CHAPTER 2

Tuesday 1st February

Everything about Manhattan was white, from the sidewalk beneath Major Jalal's boots to the static in his Sony earbead that told the major his boss was off-line again. White streets, white cars, white noise--one way or another snow was responsible for the lot. Well, maybe not the white noise.

Five hours earlier, the windchill along Fifth Avenue had been enough to make grown men cry but now the wind was gone, snow fluttered down between the Knox building and Lane Bryant like feathers from a ruptured pillow and the avenue ahead of him was as empty as the major's crocodile-skin wallet.

While his boss sat snug in Casino 30/54 losing sums of money the major could barely imagine, Major Jalal had been down to Mount Olive trying to bribe his way into the private room of Charlie Vanhie, the Boston photographer currently being wired for a broken jaw.

The contents of his wallet had gone to the pocket of a porter who took the lot and never came back. And then, when the major gave up in disgust, six sour-faced paparazzi appeared out of nowhere to grab frantic shots of him leaving the hospital, in the mistaken belief that the quietly dressed, moustachioed aide-de-camp was his Armani-clad, elegantly bearded boss. The major just hoped His Excellency was having a better night of it.

Unfortunately, Kashif Pasha wasn't.

Although the casino was in New York and His Excellency came from Ifriqiya, the roulette wheel at which he played originated in Paris. This ensured it had only one nonpaying number rather than the zero and double zero found on US tables. It was French because Kashif Pasha placed bets so high he could dictate the choice of wheel, thus limiting the edge allowed to the house. But for all this Kashif Pasha was still losing. (A situation drearily familiar to his aged mother, the Lady Maryam, his father and his bankers.)

"Excellency . . ."

Looking up, Kashif Pasha was in time to see an apologetic croupier lean forward and rake ten scarlet chips from the grid. So busy had he been listening to the dying clatter of the ivory ball that he'd forgotten to check on which number it landed. To Kashif's ear that unmistakable, addictive clicking was pitched somewhere between an old man's death rattle and the tapping of an infestation of wood beetle.

Both of which reminded him of home.

"You there." Kashif Pasha tried to snap his fingers and winced, making do with a quick wave of his injured hand. The effect was identical. A young black woman in a short deerskin skirt hurried forward, a box of cigars open on her silver tray. Her legs were bare, her breasts laced into a tan waistcoat that otherwise gaped down the front. A badge shaped like a feather announced her as Michelle.

"Sir . . ." The waitress waited for the well-dressed foreigner to select a Monte Cristo and take the matches she offered. Something Kashif Pasha did without appearing to notice the bitten nails of his own hands, which spoke of long nights and too little sleep.

Embossed on the matchbox was a tomahawk. The casino's designer had no idea if Mohawk Indians actually fought with hand axes or, indeed, if any Native Americans had ever used such weapons, but tomahawk sounded like Mohawk and 30 West 54th Street was Mohawk land.

Before it became such, the land on which Casino 30/54 sat belonged to Clack Associates, owners of a small hotel much loved by rich European tourists. Augustus Clack III sold the hotel for an undisclosed sum to the billionaire financier, Benjamin Agadir, who promptly swapped it with the Mohawks for seven glass necklaces and a blanket. Since federal regulations specifically allowed casinos to be opened on reservations or any Indian land held in trust, this neatly circumvented the state law that banned the establishment of casinos in New York City.

"Faites vos jeux," announced the croupier, as if inviting a whole table of high rollers to place their bets rather than just the one.

Kashif Pasha ignored the man.

Striking a match, the eldest son and current heir to the Emir of Tunis lifted the match to the tip of his cigar and sucked. His mother disapproved of smoking, gambling, whores and alcohol but since cigars were not expressly mentioned in the Holy Quran, she sometimes kept her peace. Besides, Kashif Pasha was in New York City and she was not.

Quite what Lady Maryam would have made of the striking murals in the gentlemen's lavatory it was best not to imagine. Kashif Pasha's favourite by far featured Pocahontas undergoing what Americans called double entry. For what were undoubtedly good cultural reasons, her lovers both sported tails, the back legs of goats, and small horns.

At home there were no paintings in Lady Maryam's wing of the Bardo and no statues. Even his great-grandfather's famous Neue Sachlichkeit collection of oils had been banished, saved only by the Emir's flat refusal to have them destroyed.

Representative art was abhorrent to his mother for usurping the rights of God. But then this was a woman who found even calligraphy suspect. Which, undoubtedly went some way to explaining why she'd burned the present his father sent her at Kashif's birth. (An Osmanli miniature from the sixteenth century showing the Prophet's wet nurse Hamina breast-feeding.) And this, in turn, maybe helped explain why Emir Moncef had refused to see his wife since.

Kashif Pasha smiled darkly, his favourite expression, and pushed five ivory chips onto the number thirteen.

"Rien ne va plus," announced the croupier, as if he hadn't been waiting. No more bets were to be made. There was a ritual to go through, even though the room was almost empty and the roulette table reserved for Kashif Pasha. The wheel spun one way and the ivory ball was sent tumbling another and when a number other than thirteen came up, Kashif Pasha just shrugged, carelessly he hoped.

Over the course of the next hour the rampart of counters in front of him became a single turret, then little more than ruined foundations and finally almost disappeared, leaving Kashif Pasha with only six ivory chips.

The casino would keep the table open for him while Kashif Pasha ordered more counters, that much was given. High rollers like His Excellency got what they wanted. Their own suites, complimentary meals, limousines to and from the airport. Even use of the casino's own plane if necessary. And what he wanted now was a break.

"Okay," said Kashif Pasha. "I'll be back here at . . ." He glanced at his Rolex and added two hours to the time it was. "At seven," he said. "Have the table reset. New wheel, new ball, new grid, new stack of counters." Which was what his croupier seemed to call those hundred-thousand-dollar red chips.

Tuesday 1st February

"Out of my way." Major Jalal jabbed his elbow into the kidney of one photographer and shouldered another into the gutter, watching as frozen slush filled the man's scruffy shoes. Ten paces at most separated the limo from the door of the casino but five photographers barred the way. Well, three now.

"Chill," his boss said with a broad smile. The major wasn't sure if that was an order or if His Excellency was commenting on New York's weather. So Jalal kept his reply to a nod, which covered both bases.

"Prince . . ."

"Over here . . ."

His Excellency Kashif Pasha was used to catcalls and noise from nasrani paparazzi, who whistled at him like he was someone's dog. It was the only thing he hated about coming to New York.

"Look this way."

Kashif Pasha made the mistake of doing just that and found himself staring into the smirking face of Charlie Vanhie, a WASP reporter he'd had the misfortune to meet at least three times before.

"Tell us about your plan to throw a dinner to celebrate your parents' fiftieth wedding anniversary . . ."

Having made the mistake of looking at Charlie Vanhie, the pasha then compounded his error by actually speaking to the man. "Forty-fifth," he corrected, "it will be their forty-fifth."

"What makes you think the Emir will turn up?"

Kashif Pasha stared at the man.

"Given that he won't even be in the same room as your mother. What was it he called her . . . ?"

Major Jalal began to move towards the speaker but His Excellency held up one hand. "Leave it," he told the major. "Let me handle this."

Around the time Kashif Pasha stood on a snow-covered sidewalk in Manhattan, bathed in the light of a flashgun, a small girl sat at a cheap plastic laptop. She was preparing to answer a long list of EQ questions, most of them multiple choice.

Draped around the girl's neck was a grey kitten worn like a collar. Actually, Ifritah was almost six months old but she still behaved like a kitten so that was how the girl thought of her.

Lady Hana al-Mansur, wrote the girl in a box marked name. Then she deleted it and typed Hani instead. There was also a box for her age but this was more problematic since no one was quite sure. She chose 10, because either she was about to become ten, or she was ten already, in which case she'd be eleven in less than a week.

In the box marked nationality Hani wrote Ottoman and when the software rejected this she wrote it again. So then the computer offered her a long list of alternatives which she rejected, finally compromising on Other.

The room where Hani sat was in a house five thousand five hundred and seven miles from New York. In El Iskandryia. A city on the left-hand edge of the Nile Delta. Right at the top where the delta jutted out into the Mediterranean.

The madersa looked in on itself in that way many North African houses do. It was old and near decrepit in places. With a grand entrance onto Rue Sherrif at the front and an unmarked door that led out to an alley at the rear.

Guarding this door was a porter named Khartoum, because the city of Khartoum was where he came from and he'd refused to reveal any other. He smoked cigars backwards, with the lit end inside his mouth and had given Hani a tiny silver hand on a thread of cotton to help her do well in the tests.

This impressed Hani greatly and it went, almost without saying, that Hani would rather have had Khartoum with her than the cat but her uncle, the bey, had forbidden it. Not crossly. Just firmly. Because the box containing the test stated that all computers were to be off-line and no other people were to be in the room when the test was taken.

First off was an easy question about being caught in a plane crash. With her plane going down would she: 1) scribble her will on the back of an envelope; 2) offer her help to the pilot; 3) continue to read a magazine?

The answer was obviously continue to read since, a) she'd never learned to fly and so offering help was pointless and, b) she was unlikely to be carrying an envelope, had she had anything to leave anybody which she didn't . . .

Next question was about her father/stepfather/legal other. Since Hani had never met the first, lacked the second and was uncertain if her Uncle Ashraf counted as the third, she ignored it, as she did two more questions about her family.

Then there was a section on school friends, which Hani didn't even bother to read. The final bit was the simplest . . . Five hundred faces on a flat screen, each expressing anger or joy, happiness, boredom, sadness or pain.

Her job was to name that emotion. The section started at a crawl and for the first twenty or so faces Hani thought this was as fast as the software could go, but as impatience set in and Hani started hammering at the keys, her screen became a blur and soon the small girl was selecting answers so fast her computer had all its fans running.

She got every expression right except for five benchmark indicators where the picture was of her. Even so, according to the EQ software, Hani's was the highest score ever recorded for that section, certainly within the time.

The IQ test that followed was infinitely more difficult. So difficult in fact that Hani ran out of time on her very first question. Which was the odd animal out--a sheep, a hen, a dog or a shark? Above each choice was the small photograph, just in case she'd forgotten what the animals looked like.

As answers went, the shark seemed much too obvious. Especially given this was an intelligence test and identifying the first three as air-breathing and the shark as a cartilaginous water dweller took no intelligence at all.

So what else could it be? Sheep were actually domesticated goats. At least Hani was pretty sure they were. Hens had also been domesticated, as had dogs, which were really domesticated wolves. So the answer could be shark but for a less obvious reason, because humanity had no history of domesticating sharks.

But what if that was still too obvious?

In the end she chose the sheep over the hen, dog and shark because it was a herbivore and all the others ate meat. Although, in the case of the hen, Hani suspected that the bird was actually omnivorous. This seemed the mostly likely of the nineteen possible answers she jotted onto a piece of scrap paper.

"So what went wrong?" her uncle asked later, when he finally tracked Hani down to the madersa's roof where the girl sat oblivious to a cold glowering sky.

"With what?"

"Your second test. You only did one question and even then . . ." His voice trailed away.

"It wasn't the sheep?"

The thin man with the shades, goatee beard and drop-pearl earring shook his head.

"Which one was it?" Hani demanded.

"The shark."

"Because it's not domesticated?"

Ashraf al-Mansur, known also as Ashraf Bey, put his face in his hands and for a moment looked almost ill. He had a niece half the city thought was retarded. A mistress who wasn't his mistress because they'd never actually fucked. And his own life . . . Raf stopped, considering that point.

He'd recently resigned his job, the madersa cost more to run than he had coming in and yet, between them, Hani and Zara were worth millions. He was being chased for debts while living in a house with two of North Africa's wealthiest people, either of whom would give him the money, if only he'd stop refusing to consider it. As Zara said, getting that to make sense was like trying to fasten jeans with a zip one side and buttonholes the other.

Hani sat her test again next morning. This time on the flat roof of the al-Mansur madersa. And she did exactly what her uncle suggested, which was give the most obvious answer to everything. It took her less than fifteen minutes to achieve a score higher than the software could handle.

CHAPTER 2

Tuesday 1st February

Everything about Manhattan was white, from the sidewalk beneath Major Jalal's boots to the static in his Sony earbead that told the major his boss was off-line again. White streets, white cars, white noise--one way or another snow was responsible for the lot. Well, maybe not the white noise.

Five hours earlier, the windchill along Fifth Avenue had been enough to make grown men cry but now the wind was gone, snow fluttered down between the Knox building and Lane Bryant like feathers from a ruptured pillow and the avenue ahead of him was as empty as the major's crocodile-skin wallet.

While his boss sat snug in Casino 30/54 losing sums of money the major could barely imagine, Major Jalal had been down to Mount Olive trying to bribe his way into the private room of Charlie Vanhie, the Boston photographer currently being wired for a broken jaw.

The contents of his wallet had gone to the pocket of a porter who took the lot and never came back. And then, when the major gave up in disgust, six sour-faced paparazzi appeared out of nowhere to grab frantic shots of him leaving the hospital, in the mistaken belief that the quietly dressed, moustachioed aide-de-camp was his Armani-clad, elegantly bearded boss. The major just hoped His Excellency was having a better night of it.

Unfortunately, Kashif Pasha wasn't.

Although the casino was in New York and His Excellency came from Ifriqiya, the roulette wheel at which he played originated in Paris. This ensured it had only one nonpaying number rather than the zero and double zero found on US tables. It was French because Kashif Pasha placed bets so high he could dictate the choice of wheel, thus limiting the edge allowed to the house. But for all this Kashif Pasha was still losing. (A situation drearily familiar to his aged mother, the Lady Maryam, his father and his bankers.)

"Excellency . . ."

Looking up, Kashif Pasha was in time to see an apologetic croupier lean forward and rake ten scarlet chips from the grid. So busy had he been listening to the dying clatter of the ivory ball that he'd forgotten to check on which number it landed. To Kashif's ear that unmistakable, addictive clicking was pitched somewhere between an old man's death rattle and the tapping of an infestation of wood beetle.

Both of which reminded him of home.

"You there." Kashif Pasha tried to snap his fingers and winced, making do with a quick wave of his injured hand. The effect was identical. A young black woman in a short deerskin skirt hurried forward, a box of cigars open on her silver tray. Her legs were bare, her breasts laced into a tan waistcoat that otherwise gaped down the front. A badge shaped like a feather announced her as Michelle.

"Sir . . ." The waitress waited for the well-dressed foreigner to select a Monte Cristo and take the matches she offered. Something Kashif Pasha did without appearing to notice the bitten nails of his own hands, which spoke of long nights and too little sleep.

Embossed on the matchbox was a tomahawk. The casino's designer had no idea if Mohawk Indians actually fought with hand axes or, indeed, if any Native Americans had ever used such weapons, but tomahawk sounded like Mohawk and 30 West 54th Street was Mohawk land.

Before it became such, the land on which Casino 30/54 sat belonged to Clack Associates, owners of a small hotel much loved by rich European tourists. Augustus Clack III sold the hotel for an undisclosed sum to the billionaire financier, Benjamin Agadir, who promptly swapped it with the Mohawks for seven glass necklaces and a blanket. Since federal regulations specifically allowed casinos to be opened on reservations or any Indian land held in trust, this neatly circumvented the state law that banned the establishment of casinos in New York City.

"Faites vos jeux," announced the croupier, as if inviting a whole table of high rollers to place their bets rather than just the one.

Kashif Pasha ignored the man.

Striking a match, the eldest son and current heir to the Emir of Tunis lifted the match to the tip of his cigar and sucked. His mother disapproved of smoking, gambling, whores and alcohol but since cigars were not expressly mentioned in the Holy Quran, she sometimes kept her peace. Besides, Kashif Pasha was in New York City and she was not.

Quite what Lady Maryam would have made of the striking murals in the gentlemen's lavatory it was best not to imagine. Kashif Pasha's favourite by far featured Pocahontas undergoing what Americans called double entry. For what were undoubtedly good cultural reasons, her lovers both sported tails, the back legs of goats, and small horns.

At home there were no paintings in Lady Maryam's wing of the Bardo and no statues. Even his great-grandfather's famous Neue Sachlichkeit collection of oils had been banished, saved only by the Emir's flat refusal to have them destroyed.

Representative art was abhorrent to his mother for usurping the rights of God. But then this was a woman who found even calligraphy suspect. Which, undoubtedly went some way to explaining why she'd burned the present his father sent her at Kashif's birth. (An Osmanli miniature from the sixteenth century showing the Prophet's wet nurse Hamina breast-feeding.) And this, in turn, maybe helped explain why Emir Moncef had refused to see his wife since.

Kashif Pasha smiled darkly, his favourite expression, and pushed five ivory chips onto the number thirteen.

"Rien ne va plus," announced the croupier, as if he hadn't been waiting. No more bets were to be made. There was a ritual to go through, even though the room was almost empty and the roulette table reserved for Kashif Pasha. The wheel spun one way and the ivory ball was sent tumbling another and when a number other than thirteen came up, Kashif Pasha just shrugged, carelessly he hoped.

Over the course of the next hour the rampart of counters in front of him became a single turret, then little more than ruined foundations and finally almost disappeared, leaving Kashif Pasha with only six ivory chips.

The casino would keep the table open for him while Kashif Pasha ordered more counters, that much was given. High rollers like His Excellency got what they wanted. Their own suites, complimentary meals, limousines to and from the airport. Even use of the casino's own plane if necessary. And what he wanted now was a break.

"Okay," said Kashif Pasha. "I'll be back here at . . ." He glanced at his Rolex and added two hours to the time it was. "At seven," he said. "Have the table reset. New wheel, new ball, new grid, new stack of counters." Which was what his croupier seemed to call those hundred-thousand-dollar red chips.

Recenzii

"Skillfully blends a hard-boiled whodunit with SF and alternate history.... Grimwood makes his imagined world feel real."--Publishers Weekly