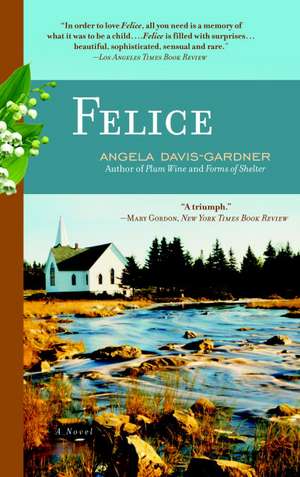

Felice

Autor Angela Davis-Gardneren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2007

Preț: 83.90 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 126

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.06€ • 16.74$ • 13.34£

16.06€ • 16.74$ • 13.34£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385340960

ISBN-10: 0385340966

Pagini: 337

Dimensiuni: 135 x 208 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Dial Press

ISBN-10: 0385340966

Pagini: 337

Dimensiuni: 135 x 208 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.26 kg

Editura: Dial Press

Notă biografică

Angela Davis-Gardner spent a year in Japan as a visiting professor at Tokyo’s Tsuda College, which inspired her acclaimed novel Plum Wine, as well as her latest novel, Butterfly's Child. She is also the author of Felice and Forms of Shelter. An Alumni Distinguished Professor Emerita at North Carolina State University, she lives in Raleigh.

Extras

Chapter One

When Blanche Melanson upset a dish of crab-apple jelly on Mother Superior's pristine white tablecloth, Sister Agatha proclaimed it a sign. A sign of what, she did not care to say. But she was not pressed on this point, for of all those present in the convent dining room that December noon, only Felice Belliveau paid attention to the content as well as the form of Sister Agatha's outburst.

All the others seated at the three circular tables looked outraged or amused, according to their general dispositions, when, after Sister Theodota's reprimand of Blanche (which stained that girl's pasty cheeks as red as the pickled beets upon her plate), Sister Agatha stood and, with her finger trembling like the gelatinous mass she pointed toward, cried, "A sign, Sisters, a sign."

"Ridiculous," Sister Theodota countered, with a volume that carried to the head table at the far end of the room. Mother Superior rose halfway from her chair and looked sternly toward the offender, while beside her the Abbe Sosonier, who appeared, seated amongst the black-frocked females, like a fly serenely caught in molasses, attended to his fish and potatoes as though nothing were amiss. The Doucette twins, dining at Mother Superior's table by virtue of the pink good-conduct ribbons pinned to their collars, smirked. At Sister Agatha's table Sister Claire looked worried, Sister Theodota's brow lowered as threateningly as the Nova Scotia sky before a winter storm, the irrepressible Celeste Rouget giggled, and the novice Evangeline crossed herself. But no less than an hour later, when the young ladies worked at their needlepoint in the parlor and the nuns knelt in the chapel, most members of L'Academie du Sacre Sang had doubtless forgotten the particulars in the sequence of events that climaxed with Sister Agatha being unceremoniously hustled from the dining hall up to her room.

But not Felice. Permanently stored in her memory was the image of the aged nun rising from her place just across the table, pointing at the offending glob of jelly (had she raised her finger just six inches she would have pointed straight at Felice's heart), and moistening her lips with a tongue that seemed too large for her mouth. Recalling the moment later, it seemed to Felice that she had sensed, an instant before Sister Agatha spoke, what the words would be. "A sign, Sisters, a sign": Felice, months afterward, would imagine her lips moving in silent unison as Sister Agatha uttered that prophecy. And all her life Felice would remember the moment just after, when Sister Agatha's eyes, wobbling and magnified behind thick spectacles, found her own face, focused and fixed there, the nun and the girl held together for one long, breath-holding instant before Sister Agatha was rudely jerked down.

Felice had always been attentive, even before her Uncle Adolphe had deposited her at the convent school on the western coast of Nova Scotia about a year ago. But in this harsh and unfamiliar climate—the dank halls, the classrooms so cavernous as to swallow up her timid, reciting voice, the dormitory, where she lay looking up into the dark, willing back tears—here Felice's powers of observation were greatly heightened. Conversation, glances, the inclination of a head or hand, the juxtaposition of objects in a room, the shapes of clouds gathering above the bay, the language of the waves that spanked the cove just below the cliff—everything she saw and heard, and even that which she tasted, smelled, and sensed—everything Felice collected as evidence. As evidence of what, she had no clear notion; the collection was itself random but thorough, impressions stored up in much the same way Mother Superior saved bits of string, scraps of cloth, candle-ends, material that might be useful later.

Yet it was not only this general penchant for close observation that caused Felice to notice and to mull over all particulars of Sister Agatha's behavior. Much of the attraction lay in Sister Agatha herself, whom Felice had watched from across the table three times a day (except on fast days, when she watched her in the chapel, or on the days of Sister Agatha's illness, when the girl tiptoed up to her cell and asked if she could be of service); it was Sister Agatha, her sad and powerful and mysterious presence, who was particularly compelling to Felice.

When eating, Sister Agatha sat poised like a bird of prey, her attention fixed on the dark pottery plate, bowl, and cup below her with such an intensity as to seem vengeful. Once upon a time, the kitchenmaid Soukie told Felice, Sister Agatha had eaten from Mother Superior's prized Haviland china like everyone else; when she began to mistake the roses patterned on the plates for morsels of food, Mother Superior had ordered the black dishes for her. Stark against the white cloth, these dishes were now the only objects on the table her eyes could distinguish in the gray flicker of her visual world. All the more wonder, Felice thought, that Sister Agatha had pointed exactly at the jelly; but then, as the nun had often warned her students before her forced retirement, her ears had eyes, and, as she had once confided to Felice, her bridegroom Jesus sometimes caused her to see everything suddenly illuminated in one great glorious burst of light.

Sister Agatha had been at the convent forty years, long enough for a body of legend to accumulate about her. Felice spent a good deal of time trying to reconcile the extant version of Sister Agatha's younger self—lovely, bright-eyed, and intractable—with the decrepit figure she had become. When as a young woman Sister Agatha (the former Catherine Comeau Starr) had come to the convent from Cape Breton—leaving behind, it was said, a broken-hearted privateer who wanted to take her back to his native Barbados—she had painted, in rich tones of sienna, gold, and scarlet, the stations of the cross in the outer chapel and the frescoes on the walls of the classrooms and halls. It was said that she had done the first painting (sinuous figures in a lush Eden) on the wall of her own cell without prelude, without permission, just after taking the veil. Some years later she had transformed the second-floor corridor with a painting of the martyrdom of Saint Agatha, the virgin's breasts being borne away on a huge platter by Roman soldiers while Agatha hid her loss beneath her arms and her doubled-over torso. It was one of the school's stories—slightly revised by each generation of students—that Sister Agatha's own breasts had been torn from her chest with hot tongs by the priest who had discovered her first painting. Felice's contribution to the legend was that her persecutor had been the Abbe Gerard Sosonier, though that mild-mannered man would have been but a child during Sister Agatha's early, troubled conventical years.

Though most of the girls chose to see Sister Agatha as comic, Felice perceived her as unutterably forlorn, mistreated, abandoned. The wrinkles in her almond-shaped face all pointed down, except when one of the gleeful smiles Felice watched for illuminated her face. In contrast to the other nuns' lips, which seemed uniformly trained in tight lines, Sister Agatha's mouth often worked like a child's about to cry. Even her black habit looked abject. Her skirt and veil were not starched, as were those of the other sisters, but lay wilted on her thin frame, and did nothing to disguise the slight hump of her back nor the protuberance of her belly. The glazed bonnet of the order, looking on the other nuns like cheerfully burnt pastries, was in Sister Agatha's case green-tinged and misshapen with age. The rosary that hung from her waist was of wide-spaced, silent urine-colored beads. The other sisters had rosaries of silver that looked, as they clicked busily down the halls or across the grounds, like glinting crossed knives in the depths of their dark skirts.

Felice had been in Sister Agatha's Latin and English literature classes last spring, the nun's final term of teaching. Sister Agatha's favorite textbook authors were Catullus, Herrick, Marvell, and Donne, but she also liked to quote the recently published Gerard Manley Hopkins; he was, she told Felice (whom she had chosen to read the verse aloud to her after classes), her spiritual brother.

Mother Superior was said to disapprove of the students' being exposed to modern poetry; she was also displeased that Caesar and the Gallic wars, supposed to occupy a major place in the Latin curriculum, had been almost entirely supplanted by the love poems of Catullus. And although she was, in general, a supporter of Sister Agatha, Mother Superior did not particularly admire the evolution of the nun's teaching style, which had come to consist almost entirely of student and teacher recitations. Mother Superior offered to mark written tests for her, but Sister Agatha clung to the oral examinations in which the girls were asked to name their favorites of a given group of poems or poets, the highest marks going to those students whose tastes matched her own. Good marks on final exams, therefore, were easy to come by, but the recitations—also part of the cumulative grade—were more difficult. Sometimes the girls had been tempted to refer to a surreptitiously opened text to help them through, but this was done only in the most extreme emergencies, for it was felt that Sister Agatha—even though she did not say so—somehow knew of these transgressions. Sister Agatha could not only recite each poem word for word, but her hands could find, almost miraculously, it seemed, where each lay in the book. But often she had left the book, and her desk, to recite an impassioned verse while swaying about the platform, so that the suspense of whether she would step too far engrossed the students at the expense of Catullus or Marvell. The image of Sister Agatha at the brink of the platform was inextricably bound with Felice's memory of the love poems, and the plaintive, hypnotic voice in which they were recited.

Last May Mother Superior had informed Sister Agatha that it was time for her to retire from teaching. In protest, the aging nun had risen during the next day's mass and stood cruciform before the statue of the Virgin Mary. The spectacle of Sister Agatha trembling before them, her arms outstretched as though in penance, caused such rustlings in the sisters' pews and commotion in the girls' section—where Felice was one of the very few not to giggle—that it had been necessary to escort the nun out. Soon thereafter she had initiated her practice of spontaneous speeches during meals, a situation that, Sister Theodota had been heard to observe, simply could not much longer be tolerated.

One day near the end of the term, Felice had been drawn aside by Sister Agatha in the hall and bestowed with the title of "My favorite student, in all these many years." Not long after, when Felice had carried a bowl of gruel to Sister Agatha in her cell, where she was enduring the monthly illness that had abruptly resumed on the day of her retirement (and which condition was not only a sham but likely to disgrace them all, most of the sisters agreed), the nun whispered, "O child, hold this secret: I am not unclean, it is only from my hands that I bleed, only from my hands." And she lifted the hands, pale and trembling, toward heaven before lowering them and taking the girl's hands into her own. "God gave me one last year of teaching," she told Felice, "so that I might know you, and light your way."

Each of the students at the convent had a particular favorite among the nuns, a paragon whose mannerisms and acts were carefully observed and then compared, in friendly rivalry, with those of the other girls' ideals. In this sub rosa contest that continued year after year, Mother Superior, Sister Constance, and Sister Claire were perennial favorites. Mother Superior's following had greatly increased since she had expressed the opinion—out in public, where even the Abbe could have heard her—that female suffrage, recently approved in Canada, was not only commendable but morally correct. Sister Constance, with her small oval face, her features as perfectly formed as those of a wedding-cake figure, and her short, square teeth perpetually framed by a smile, had long been the standard of female beauty at the convent, but was considered by the present generation of students to be a bit too sweet. Sister Claire, the good-natured music teacher, remained popular even as she aged; Felice, who was considered her best piano student, was officially the current leader of Sister Claire's claque. But, privately, Felice had shifted her chief allegiance in recent months to Sister Agatha, who, other than her protegee Evangeline (lately become a novice, and therefore no longer considered a girl), had among the girls only detractors.

Thus it was not only because of her custom of attentiveness that Felice fixed every detail of that December luncheon so vividly in her memory. It was also as Sister Agatha's self-appointed champion and protector that she memorized each utterance, gesture, and expression, and in this Felice herself displayed foresight; weeks and then months later she would be able to recapture this day for a circle of admiring friends, and to bask in the shared glory of Sister Agatha's vision.

After Sister Agatha's outburst, though all observers attempted to appear scrupulously disinterested, Felice sensed the congealing of tension in the room, a tension binding them all in an uneasy union. Felice noted how Sister Theodota's left hand, the same one that had grasped Sister Agatha's skirt and pulled her back down to her seat, lay for a moment upon the table, still fisted. She saw the glances exchanged among the nuns, and ceasing to eat, she watched Sister Agatha's struggle against tears. As Sister Theodota made short work of the jelly cleanup—scooping it up in her napkin and setting the napkin at the edge of the table for Soukie—Felice observed the nun's lips, pursed so severely that they nearly disappeared. At the same time Felice was also aware—as the other diners, preoccupied with the cleanup, were not—of the light dawning behind Sister Agatha's face and gradually suffusing it, a light which caused her to lay down her fork and to lift her eyes toward the crucifix on the wall.

When Sister Agatha chanted, "Gloria in excelsis Deo," Felice was expecting a speech; Sister Theodota, who was not, jumped, jabbing her fork into her lower lip.

"Lay out the waxed linen cloths, Sisters, my beatification is at hand."

Sister Theodota glared at Sister Agatha, then said in a strangled, saccharine voice, "Yes, dear, we know." Turning her face about the table like a searchlight, the nun focused on Blanche, who cringed, and then on Celeste. "Mademoiselle Rouget, I believe it is your turn to clear?"

Celeste rose, and with an ironical glance toward Felice, lifted the tureen of cod and potatoes and carried it toward the kitchen.

When Blanche Melanson upset a dish of crab-apple jelly on Mother Superior's pristine white tablecloth, Sister Agatha proclaimed it a sign. A sign of what, she did not care to say. But she was not pressed on this point, for of all those present in the convent dining room that December noon, only Felice Belliveau paid attention to the content as well as the form of Sister Agatha's outburst.

All the others seated at the three circular tables looked outraged or amused, according to their general dispositions, when, after Sister Theodota's reprimand of Blanche (which stained that girl's pasty cheeks as red as the pickled beets upon her plate), Sister Agatha stood and, with her finger trembling like the gelatinous mass she pointed toward, cried, "A sign, Sisters, a sign."

"Ridiculous," Sister Theodota countered, with a volume that carried to the head table at the far end of the room. Mother Superior rose halfway from her chair and looked sternly toward the offender, while beside her the Abbe Sosonier, who appeared, seated amongst the black-frocked females, like a fly serenely caught in molasses, attended to his fish and potatoes as though nothing were amiss. The Doucette twins, dining at Mother Superior's table by virtue of the pink good-conduct ribbons pinned to their collars, smirked. At Sister Agatha's table Sister Claire looked worried, Sister Theodota's brow lowered as threateningly as the Nova Scotia sky before a winter storm, the irrepressible Celeste Rouget giggled, and the novice Evangeline crossed herself. But no less than an hour later, when the young ladies worked at their needlepoint in the parlor and the nuns knelt in the chapel, most members of L'Academie du Sacre Sang had doubtless forgotten the particulars in the sequence of events that climaxed with Sister Agatha being unceremoniously hustled from the dining hall up to her room.

But not Felice. Permanently stored in her memory was the image of the aged nun rising from her place just across the table, pointing at the offending glob of jelly (had she raised her finger just six inches she would have pointed straight at Felice's heart), and moistening her lips with a tongue that seemed too large for her mouth. Recalling the moment later, it seemed to Felice that she had sensed, an instant before Sister Agatha spoke, what the words would be. "A sign, Sisters, a sign": Felice, months afterward, would imagine her lips moving in silent unison as Sister Agatha uttered that prophecy. And all her life Felice would remember the moment just after, when Sister Agatha's eyes, wobbling and magnified behind thick spectacles, found her own face, focused and fixed there, the nun and the girl held together for one long, breath-holding instant before Sister Agatha was rudely jerked down.

Felice had always been attentive, even before her Uncle Adolphe had deposited her at the convent school on the western coast of Nova Scotia about a year ago. But in this harsh and unfamiliar climate—the dank halls, the classrooms so cavernous as to swallow up her timid, reciting voice, the dormitory, where she lay looking up into the dark, willing back tears—here Felice's powers of observation were greatly heightened. Conversation, glances, the inclination of a head or hand, the juxtaposition of objects in a room, the shapes of clouds gathering above the bay, the language of the waves that spanked the cove just below the cliff—everything she saw and heard, and even that which she tasted, smelled, and sensed—everything Felice collected as evidence. As evidence of what, she had no clear notion; the collection was itself random but thorough, impressions stored up in much the same way Mother Superior saved bits of string, scraps of cloth, candle-ends, material that might be useful later.

Yet it was not only this general penchant for close observation that caused Felice to notice and to mull over all particulars of Sister Agatha's behavior. Much of the attraction lay in Sister Agatha herself, whom Felice had watched from across the table three times a day (except on fast days, when she watched her in the chapel, or on the days of Sister Agatha's illness, when the girl tiptoed up to her cell and asked if she could be of service); it was Sister Agatha, her sad and powerful and mysterious presence, who was particularly compelling to Felice.

When eating, Sister Agatha sat poised like a bird of prey, her attention fixed on the dark pottery plate, bowl, and cup below her with such an intensity as to seem vengeful. Once upon a time, the kitchenmaid Soukie told Felice, Sister Agatha had eaten from Mother Superior's prized Haviland china like everyone else; when she began to mistake the roses patterned on the plates for morsels of food, Mother Superior had ordered the black dishes for her. Stark against the white cloth, these dishes were now the only objects on the table her eyes could distinguish in the gray flicker of her visual world. All the more wonder, Felice thought, that Sister Agatha had pointed exactly at the jelly; but then, as the nun had often warned her students before her forced retirement, her ears had eyes, and, as she had once confided to Felice, her bridegroom Jesus sometimes caused her to see everything suddenly illuminated in one great glorious burst of light.

Sister Agatha had been at the convent forty years, long enough for a body of legend to accumulate about her. Felice spent a good deal of time trying to reconcile the extant version of Sister Agatha's younger self—lovely, bright-eyed, and intractable—with the decrepit figure she had become. When as a young woman Sister Agatha (the former Catherine Comeau Starr) had come to the convent from Cape Breton—leaving behind, it was said, a broken-hearted privateer who wanted to take her back to his native Barbados—she had painted, in rich tones of sienna, gold, and scarlet, the stations of the cross in the outer chapel and the frescoes on the walls of the classrooms and halls. It was said that she had done the first painting (sinuous figures in a lush Eden) on the wall of her own cell without prelude, without permission, just after taking the veil. Some years later she had transformed the second-floor corridor with a painting of the martyrdom of Saint Agatha, the virgin's breasts being borne away on a huge platter by Roman soldiers while Agatha hid her loss beneath her arms and her doubled-over torso. It was one of the school's stories—slightly revised by each generation of students—that Sister Agatha's own breasts had been torn from her chest with hot tongs by the priest who had discovered her first painting. Felice's contribution to the legend was that her persecutor had been the Abbe Gerard Sosonier, though that mild-mannered man would have been but a child during Sister Agatha's early, troubled conventical years.

Though most of the girls chose to see Sister Agatha as comic, Felice perceived her as unutterably forlorn, mistreated, abandoned. The wrinkles in her almond-shaped face all pointed down, except when one of the gleeful smiles Felice watched for illuminated her face. In contrast to the other nuns' lips, which seemed uniformly trained in tight lines, Sister Agatha's mouth often worked like a child's about to cry. Even her black habit looked abject. Her skirt and veil were not starched, as were those of the other sisters, but lay wilted on her thin frame, and did nothing to disguise the slight hump of her back nor the protuberance of her belly. The glazed bonnet of the order, looking on the other nuns like cheerfully burnt pastries, was in Sister Agatha's case green-tinged and misshapen with age. The rosary that hung from her waist was of wide-spaced, silent urine-colored beads. The other sisters had rosaries of silver that looked, as they clicked busily down the halls or across the grounds, like glinting crossed knives in the depths of their dark skirts.

Felice had been in Sister Agatha's Latin and English literature classes last spring, the nun's final term of teaching. Sister Agatha's favorite textbook authors were Catullus, Herrick, Marvell, and Donne, but she also liked to quote the recently published Gerard Manley Hopkins; he was, she told Felice (whom she had chosen to read the verse aloud to her after classes), her spiritual brother.

Mother Superior was said to disapprove of the students' being exposed to modern poetry; she was also displeased that Caesar and the Gallic wars, supposed to occupy a major place in the Latin curriculum, had been almost entirely supplanted by the love poems of Catullus. And although she was, in general, a supporter of Sister Agatha, Mother Superior did not particularly admire the evolution of the nun's teaching style, which had come to consist almost entirely of student and teacher recitations. Mother Superior offered to mark written tests for her, but Sister Agatha clung to the oral examinations in which the girls were asked to name their favorites of a given group of poems or poets, the highest marks going to those students whose tastes matched her own. Good marks on final exams, therefore, were easy to come by, but the recitations—also part of the cumulative grade—were more difficult. Sometimes the girls had been tempted to refer to a surreptitiously opened text to help them through, but this was done only in the most extreme emergencies, for it was felt that Sister Agatha—even though she did not say so—somehow knew of these transgressions. Sister Agatha could not only recite each poem word for word, but her hands could find, almost miraculously, it seemed, where each lay in the book. But often she had left the book, and her desk, to recite an impassioned verse while swaying about the platform, so that the suspense of whether she would step too far engrossed the students at the expense of Catullus or Marvell. The image of Sister Agatha at the brink of the platform was inextricably bound with Felice's memory of the love poems, and the plaintive, hypnotic voice in which they were recited.

Last May Mother Superior had informed Sister Agatha that it was time for her to retire from teaching. In protest, the aging nun had risen during the next day's mass and stood cruciform before the statue of the Virgin Mary. The spectacle of Sister Agatha trembling before them, her arms outstretched as though in penance, caused such rustlings in the sisters' pews and commotion in the girls' section—where Felice was one of the very few not to giggle—that it had been necessary to escort the nun out. Soon thereafter she had initiated her practice of spontaneous speeches during meals, a situation that, Sister Theodota had been heard to observe, simply could not much longer be tolerated.

One day near the end of the term, Felice had been drawn aside by Sister Agatha in the hall and bestowed with the title of "My favorite student, in all these many years." Not long after, when Felice had carried a bowl of gruel to Sister Agatha in her cell, where she was enduring the monthly illness that had abruptly resumed on the day of her retirement (and which condition was not only a sham but likely to disgrace them all, most of the sisters agreed), the nun whispered, "O child, hold this secret: I am not unclean, it is only from my hands that I bleed, only from my hands." And she lifted the hands, pale and trembling, toward heaven before lowering them and taking the girl's hands into her own. "God gave me one last year of teaching," she told Felice, "so that I might know you, and light your way."

Each of the students at the convent had a particular favorite among the nuns, a paragon whose mannerisms and acts were carefully observed and then compared, in friendly rivalry, with those of the other girls' ideals. In this sub rosa contest that continued year after year, Mother Superior, Sister Constance, and Sister Claire were perennial favorites. Mother Superior's following had greatly increased since she had expressed the opinion—out in public, where even the Abbe could have heard her—that female suffrage, recently approved in Canada, was not only commendable but morally correct. Sister Constance, with her small oval face, her features as perfectly formed as those of a wedding-cake figure, and her short, square teeth perpetually framed by a smile, had long been the standard of female beauty at the convent, but was considered by the present generation of students to be a bit too sweet. Sister Claire, the good-natured music teacher, remained popular even as she aged; Felice, who was considered her best piano student, was officially the current leader of Sister Claire's claque. But, privately, Felice had shifted her chief allegiance in recent months to Sister Agatha, who, other than her protegee Evangeline (lately become a novice, and therefore no longer considered a girl), had among the girls only detractors.

Thus it was not only because of her custom of attentiveness that Felice fixed every detail of that December luncheon so vividly in her memory. It was also as Sister Agatha's self-appointed champion and protector that she memorized each utterance, gesture, and expression, and in this Felice herself displayed foresight; weeks and then months later she would be able to recapture this day for a circle of admiring friends, and to bask in the shared glory of Sister Agatha's vision.

After Sister Agatha's outburst, though all observers attempted to appear scrupulously disinterested, Felice sensed the congealing of tension in the room, a tension binding them all in an uneasy union. Felice noted how Sister Theodota's left hand, the same one that had grasped Sister Agatha's skirt and pulled her back down to her seat, lay for a moment upon the table, still fisted. She saw the glances exchanged among the nuns, and ceasing to eat, she watched Sister Agatha's struggle against tears. As Sister Theodota made short work of the jelly cleanup—scooping it up in her napkin and setting the napkin at the edge of the table for Soukie—Felice observed the nun's lips, pursed so severely that they nearly disappeared. At the same time Felice was also aware—as the other diners, preoccupied with the cleanup, were not—of the light dawning behind Sister Agatha's face and gradually suffusing it, a light which caused her to lay down her fork and to lift her eyes toward the crucifix on the wall.

When Sister Agatha chanted, "Gloria in excelsis Deo," Felice was expecting a speech; Sister Theodota, who was not, jumped, jabbing her fork into her lower lip.

"Lay out the waxed linen cloths, Sisters, my beatification is at hand."

Sister Theodota glared at Sister Agatha, then said in a strangled, saccharine voice, "Yes, dear, we know." Turning her face about the table like a searchlight, the nun focused on Blanche, who cringed, and then on Celeste. "Mademoiselle Rouget, I believe it is your turn to clear?"

Celeste rose, and with an ironical glance toward Felice, lifted the tureen of cod and potatoes and carried it toward the kitchen.

Recenzii

“Surely a spinning wheel—not a typewriter—turned out this shimmering story….You will not have loved a young girl so much since Johanna Spyri’s Heidi.” —Charlotte Observer

“Few novels glow with such warmth and delicate grace….Felice is a modest miracle of goodly feelings.” —Kansas City Star

“Style and craft are alive and well and in this book, a novel that uplifts, praises and illuminates the human spirit….Felice is the work of a writer who is in touch with the human heart.” —Raleigh News and Observer

“A warmly intimate, funny first novel…Charming…and Sister A. is a pip!” —Kirkus Reviews

“Few novels glow with such warmth and delicate grace….Felice is a modest miracle of goodly feelings.” —Kansas City Star

“Style and craft are alive and well and in this book, a novel that uplifts, praises and illuminates the human spirit….Felice is the work of a writer who is in touch with the human heart.” —Raleigh News and Observer

“A warmly intimate, funny first novel…Charming…and Sister A. is a pip!” —Kirkus Reviews

Descriere

Davis-Gardners novel, called beautiful, sophisticated, sensual and rare by the "Los Angeles Times Book Review," is back in print after more than a decade.