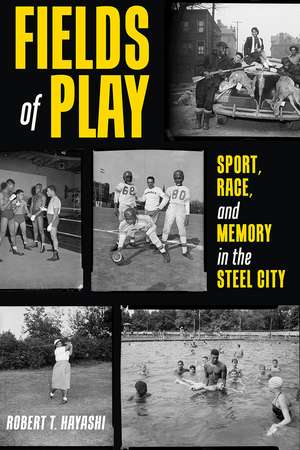

Fields of Play: Sport, Race, and Memory in the Steel City

Autor Robert Hayashien Limba Engleză Hardback – 26 sep 2023

Americans love sports, from neighborhood pickup basketball to the National Football League, and everything in between. While no city better demonstrates the connection between athletic games and community than Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the common association of the city’s professional sports teams with its blue-collar industrial past illustrates a white nostalgic perspective that excludes the voices of many who labored in the mines and mills and played on local fields. In this original and lyrical history, Robert T. Hayashi addresses this gap by uncovering and sharing overlooked tales of the region’s less famous athletes: Chinese baseball players, Black women hunters, Jewish summer campers, and coal miner soccer stars. These athletes created separate spaces of play while demanding equal access to the region’s opportunities on and off the field. Weaving together personal narrative with accounts from media, popular culture, legal cases, and archival sources, Fields of Play details how powerful individuals and organizations used recreation to promote their interests and shape public memory. Combining this rigorous archival research with a poet’s voice, Hayashi vividly portrays how coal towns, settlement houses, municipal swimming pools, state game lands, stadia, and the city’s landmark rivers were all sites of struggle over inclusion and the meaning of play in the Steel City.

Preț: 161.28 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 242

Preț estimativ în valută:

30.86€ • 33.51$ • 25.93£

30.86€ • 33.51$ • 25.93£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 aprilie

Livrare express 18-22 martie pentru 80.17 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780822947844

ISBN-10: 0822947846

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Editura: University of Pittsburgh Press

Colecția University of Pittsburgh Press

ISBN-10: 0822947846

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 43 mm

Greutate: 0.63 kg

Editura: University of Pittsburgh Press

Colecția University of Pittsburgh Press

Recenzii

"Hayashi uncovers hidden pasts, half-forgotten histories, and new angles on sporting life."

—90.5 WESA

"Part history, part memoir, and infused with the author’s feelings of alienation, belonging and nostalgia, “Fields of Play” is informative, blunt and, at times, poignant."

—Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

"A fascinating study of the complex interplay of race, gender, politics and capitalism in our local sporting life."

—Pittsburgh Magazine

“Focused on Pittsburgh’s vaunted athletic past, Fields of Play revisits the question Fitzgerald posed so well in The Great Gatsby: Who is included and who is excluded from the American Dream? With wry, devastating, and surprisingly tender insight, Robert T. Hayashi simultaneously breaks down the myths of the melting pot and the even playing field. Fields of Play is the perfect cure for our lazy hometown nostalgia.”

—Stewart O’Nan, author of Everyday People and Emily, Alone

“This is an exceedingly bracing sports book. The history of Pittsburgh comes alive through Hayashi’s sporting lens, and our sports world is enriched by seeing it through the eyes of Pittsburgh—all of Pittsburgh—itself. It’s not just the history and engaging prose. It’s the diversity of perspectives and hidden histories that set this book apart. I can only hope that because of Fields of Play, a thousand flowers will bloom, and more writers will aspire—and be inspired—to give the Hayashi treatment to their city as well.” —Dave Zirin, author of The Kaepernick Effect and sports editor, the Nation

—90.5 WESA

"Part history, part memoir, and infused with the author’s feelings of alienation, belonging and nostalgia, “Fields of Play” is informative, blunt and, at times, poignant."

—Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

"A fascinating study of the complex interplay of race, gender, politics and capitalism in our local sporting life."

—Pittsburgh Magazine

“Focused on Pittsburgh’s vaunted athletic past, Fields of Play revisits the question Fitzgerald posed so well in The Great Gatsby: Who is included and who is excluded from the American Dream? With wry, devastating, and surprisingly tender insight, Robert T. Hayashi simultaneously breaks down the myths of the melting pot and the even playing field. Fields of Play is the perfect cure for our lazy hometown nostalgia.”

—Stewart O’Nan, author of Everyday People and Emily, Alone

“This is an exceedingly bracing sports book. The history of Pittsburgh comes alive through Hayashi’s sporting lens, and our sports world is enriched by seeing it through the eyes of Pittsburgh—all of Pittsburgh—itself. It’s not just the history and engaging prose. It’s the diversity of perspectives and hidden histories that set this book apart. I can only hope that because of Fields of Play, a thousand flowers will bloom, and more writers will aspire—and be inspired—to give the Hayashi treatment to their city as well.” —Dave Zirin, author of The Kaepernick Effect and sports editor, the Nation

Notă biografică

Robert T. Hayashi is associate professor of American Studies at Amherst College. He was raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and is the author of Haunted by Waters: A Journey through Race and Place in the American West.

Extras

Excerpt from Fields of Play Chapter 5: “Terrible Towels and Sixty-Minute Men: The Pittsburgh Steelers and Forgetting a Black (and Yellow) Past”

When I see someone in a Steelers T-shirt or cap, I have to say something. “Hey, nice shirt! Go, Steelers!” Gas station, shopping mall, airport terminal, it does not matter. I have joined group cheers in public spaces at the least encouragement. I guess what I most hope to hear in reply is, “Where’d yinz live at?” And I feel a little betrayed, even annoyed otherwise. Please, don’t ever tell me you just liked the look of the shirt! Professional teams provide fans with a collective set of symbols around which we unite and signify community: “In rallying around the home team, people identify more closely with a broader civic framework in the spatially, socially, and politically fragmented metropolis.” NFL broadcasters typically note the presence of Steelers fans at contests across the country, “How well Steelers fans travel.” I have been to games in Green Bay and Atlanta where thousands and thousands of men and women dressed in black and gold have filled the seats. Cities across the US and even overseas—Zurich, Bangkok, Rio—have bars where Steeler fans gather to watch the games, cheer, suffer, and reminisce. What the TV talking heads fail to acknowledge is how many of these fans at away games are part of that exodus of workers and families who left the city when industry crashed. The Steeler Nation is a diaspora.

The early years of pro football and of the Steelers certainly did not suggest that the team would function as any collective symbol. Professional football was a relatively minor sport in the first part of the twentieth century, college football being much more popular; and it was not until the mid-twentieth century that pro football began to attract mass audiences, especially with the rise of television, its sports-specific programming, and the clever marketing of the NFL. The dramatic NFL Films, accompanied by a propulsive soundtrack, slow motion shots, and John Facenda’s godlike narration made a simple screen pass appear a distillation of epic tragedy. As noted earlier, the Steelers were perennial losers for decades. Their role in conveying local identity was due to more than their turnaround on the field—dramatic as it was—or to the growth of professional football and the mass media that has catalyzed its explosive growth. A combination of social, cultural, and economic forces during the 1970s coincided with the Steelers’ rise to become the most dominant team in the history of the NFL and provided Pittsburghers with a powerful impulse to paint their faces black and gold.

It is impossible to discuss the Steelers organization without analyzing the influence of the team’s majority owners, the Rooney family of Pittsburgh. As Dave Anderson observed, writing in the New York Times, “In any sport, a team’s character usually reflects, for better or for worse, the franchise’s dominant personality.” Although many NFL teams have experienced a slew of owners, the Steelers have remained a family business, controlled and defined by the Rooneys. The patriarch, Art Rooney, who died in 1988, was the son of Irish Catholic immigrants and grew up on the city’s North Side district, where he lived all his life. The neighborhood had once been an independent town, Allegheny City, which Pittsburgh annexed and reconfigured. . . .

The local sports historian Rob Ruck summarizes well the legendary status and influence of Art Rooney: “In the somewhat mythic but still essentially accurate saga Pittsburghers have woven out of the strands of Art Rooney’s life, sport is a product of hardworking people and tight-knit communities.” Art’s son Dan continued this legacy, even moving into his father’s former home on the North Side. Like his dad, Dan Rooney’s community was also the touchstone of his character, as he described, “I know this sounds impossible but in those days growing up on the North Side, we didn’t think about your skin color, or your accent, or what church you went to. What mattered was that you lived up to your word, pulled your own weight, and looked out for your friends.”

One of Dan Rooney’s most important decisions upon assuming operational control of the organization was the hiring of a new head coach, a young assistant coach of the Miami Dolphins and former high school star from a working-class Cleveland family. Chuck Noll immediately instilled an attitude of professionalism and commitment that echoed across the roster. The longtime kicker Gary Anderson recalls, “I really responded to a guy like that. . . . If you showed up for work in the morning, he assumed you were professional enough to get the job done.” The Steelers also displayed the toughness embodied in Art Rooney, who is famously quoted as saying, “Don’t ever let anyone mistake kindness for weakness.” The former Steeler middle linebacker Jack Lambert, a Steeler legend for his violent play and missing front teeth, which commonly elicited comparisons to Dracula, defined the Steelers’ style as a “culture of hard-hitting, hard-drinking, blue collar masculinity.” And it sold as well as Big Irons—the sixteen-ounce version of the local brew, Iron City. Opponents may have expected to win against Pittsburgh, but victory would come with its lumps. The former NFL quarterback Len Dawson recalled, “They intimidated. It began with their defense.” With Noll at the helm and a new group of exceptionally talented players, the team reached legendary prominence, just as the town’s defining economic base collapsed. Yet the Steelers, through their name, their symbols, and physical style of play, keep the memory of those hulking mills, smokestacks, and once thriving towns like Braddock alive on Sundays.

When I see someone in a Steelers T-shirt or cap, I have to say something. “Hey, nice shirt! Go, Steelers!” Gas station, shopping mall, airport terminal, it does not matter. I have joined group cheers in public spaces at the least encouragement. I guess what I most hope to hear in reply is, “Where’d yinz live at?” And I feel a little betrayed, even annoyed otherwise. Please, don’t ever tell me you just liked the look of the shirt! Professional teams provide fans with a collective set of symbols around which we unite and signify community: “In rallying around the home team, people identify more closely with a broader civic framework in the spatially, socially, and politically fragmented metropolis.” NFL broadcasters typically note the presence of Steelers fans at contests across the country, “How well Steelers fans travel.” I have been to games in Green Bay and Atlanta where thousands and thousands of men and women dressed in black and gold have filled the seats. Cities across the US and even overseas—Zurich, Bangkok, Rio—have bars where Steeler fans gather to watch the games, cheer, suffer, and reminisce. What the TV talking heads fail to acknowledge is how many of these fans at away games are part of that exodus of workers and families who left the city when industry crashed. The Steeler Nation is a diaspora.

The early years of pro football and of the Steelers certainly did not suggest that the team would function as any collective symbol. Professional football was a relatively minor sport in the first part of the twentieth century, college football being much more popular; and it was not until the mid-twentieth century that pro football began to attract mass audiences, especially with the rise of television, its sports-specific programming, and the clever marketing of the NFL. The dramatic NFL Films, accompanied by a propulsive soundtrack, slow motion shots, and John Facenda’s godlike narration made a simple screen pass appear a distillation of epic tragedy. As noted earlier, the Steelers were perennial losers for decades. Their role in conveying local identity was due to more than their turnaround on the field—dramatic as it was—or to the growth of professional football and the mass media that has catalyzed its explosive growth. A combination of social, cultural, and economic forces during the 1970s coincided with the Steelers’ rise to become the most dominant team in the history of the NFL and provided Pittsburghers with a powerful impulse to paint their faces black and gold.

It is impossible to discuss the Steelers organization without analyzing the influence of the team’s majority owners, the Rooney family of Pittsburgh. As Dave Anderson observed, writing in the New York Times, “In any sport, a team’s character usually reflects, for better or for worse, the franchise’s dominant personality.” Although many NFL teams have experienced a slew of owners, the Steelers have remained a family business, controlled and defined by the Rooneys. The patriarch, Art Rooney, who died in 1988, was the son of Irish Catholic immigrants and grew up on the city’s North Side district, where he lived all his life. The neighborhood had once been an independent town, Allegheny City, which Pittsburgh annexed and reconfigured. . . .

The local sports historian Rob Ruck summarizes well the legendary status and influence of Art Rooney: “In the somewhat mythic but still essentially accurate saga Pittsburghers have woven out of the strands of Art Rooney’s life, sport is a product of hardworking people and tight-knit communities.” Art’s son Dan continued this legacy, even moving into his father’s former home on the North Side. Like his dad, Dan Rooney’s community was also the touchstone of his character, as he described, “I know this sounds impossible but in those days growing up on the North Side, we didn’t think about your skin color, or your accent, or what church you went to. What mattered was that you lived up to your word, pulled your own weight, and looked out for your friends.”

One of Dan Rooney’s most important decisions upon assuming operational control of the organization was the hiring of a new head coach, a young assistant coach of the Miami Dolphins and former high school star from a working-class Cleveland family. Chuck Noll immediately instilled an attitude of professionalism and commitment that echoed across the roster. The longtime kicker Gary Anderson recalls, “I really responded to a guy like that. . . . If you showed up for work in the morning, he assumed you were professional enough to get the job done.” The Steelers also displayed the toughness embodied in Art Rooney, who is famously quoted as saying, “Don’t ever let anyone mistake kindness for weakness.” The former Steeler middle linebacker Jack Lambert, a Steeler legend for his violent play and missing front teeth, which commonly elicited comparisons to Dracula, defined the Steelers’ style as a “culture of hard-hitting, hard-drinking, blue collar masculinity.” And it sold as well as Big Irons—the sixteen-ounce version of the local brew, Iron City. Opponents may have expected to win against Pittsburgh, but victory would come with its lumps. The former NFL quarterback Len Dawson recalled, “They intimidated. It began with their defense.” With Noll at the helm and a new group of exceptionally talented players, the team reached legendary prominence, just as the town’s defining economic base collapsed. Yet the Steelers, through their name, their symbols, and physical style of play, keep the memory of those hulking mills, smokestacks, and once thriving towns like Braddock alive on Sundays.