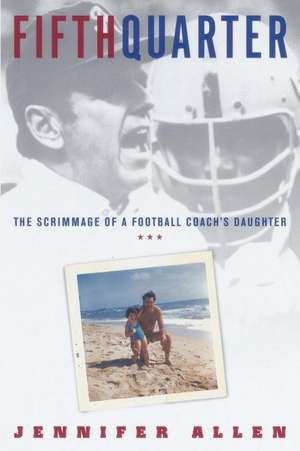

Fifth Quarter: The Scrimmage of a Football Coach's Daughter

Autor Jennifer Allenen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2000

Buffeted by the coach's tumultuous firings and hirings, the Allen family was periodically propelled to new teams in new cities. And while her French-Tunisian mother attempted to teach Jennifer proper feminine etiquette, the author dreamed of being the first female quarterback in the NFL. But as she grew up, she yearned mostly to be someone her father would notice. In a macho world where only foot-ball mattered, what could she strive for? Who could she become?

Allen has written a poignant memoir of the father she tried so hard to know, about a family life that was willfully sacrificed to his endless fanatical pursuit of the Super Bowl. What emerges is a fascinating and singular behind-the-scenes look at professional football, and a memorable, bittersweet portrait of a father and his daughter, written in a fresh and perceptive voice.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 113.46 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 170

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.72€ • 23.60$ • 18.25£

21.72€ • 23.60$ • 18.25£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780812992328

ISBN-10: 0812992326

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 154 x 234 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Random House

ISBN-10: 0812992326

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 154 x 234 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Editura: Random House

Notă biografică

Jennifer Allen is a freelance journalist and the author of Better Get Your Angel On, a collection of stories. She has contributed pieces to numerous magazines, including Rolling Stone, Mirabella, and The New Republic. Allen lives in Los Angeles with her husband, the author Mark Richard, and their sons, Roman and Deacon.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Dinner, New Year's Eve, 1968

Dad sat at the dinner table, sipping his milk. We all watched him sip his milk, his first and only drink of choice. Then he set his glass down on the table where my three older brothers and I sat, while Mom scowled as she stirred a pot of boiling spaghetti on the kitchen stove.

"Listen," Dad said, "a guy who goes out after a loss and parties is a two-time loser." Dad was referring to his ex-boss, Los Angeles Rams owner Dan Reeves. "First, he's a loser for losing, and second, he's a loser for thinking he doesn't look like a loser by partying it up."

Dan Reeves had once said, "I'd rather lose with a coach I can drink with and have fun with than win with George Allen." Reeves had been drinking all Christmas night at a Hollywood bar when he called my father at home from the bar telephone, the following day, at 8 a.m. "Merry Christmas, George," Reeves had said. "You're fired!"

That was a week ago. Now, on New Year's Eve, Dad sat in his pajamas, talking to us kids at the dinner table. Mom stood in her bathrobe, clanging pots and pans on the stove. This was a rare dinner with Dad since he had taken the job as head coach of the Los Angeles Rams three years before. For my father, getting the Rams to the National Football League Championship meant drinking a tall glass of milk at the office for dinner, then spending the night on his office couch so that he wouldn't waste valuable work time driving home, eating with his family, and sleeping with his wife. The long hours paid off: the 1968 Rams defense had set a new fourteen-game record for fewest yards allowed on offense. But the team finished second in the Coastal Division, falling two games short of reaching the championship play-offs. A week later, Dan Reeves fired Dad. Since then, we had been keeping the TV volume turned down low so as not to disturb Dad's weeklong monologue, which had begun the day after Christmas.

"Heck," Dad said, "Dan Reeves is dying of cancer. Maybe that's his problem. He's drinking to forget he's alive!"

We all knew what came next. When talking about drinking and dying, our father always cited his own father, Earl, who died an unemployed alcoholic. To our father, the only thing worse than losing was dying without a job. "I want to die working," Dad told us all. "That's the only way to die!"

"Dying," Mom said, setting down Dad's plate of spaghetti. "Who's talking about dying? I thought we were going to have a nice dinner together for once in our lives."

"I'm trying to teach these kids a lesson."

"They've learned enough as it is."

"You know," our father said as our mother finished serving dinner, "you kids have a lot to learn about life."

We kids nodded. We twisted our forks into our spaghetti as Dad told us again about his other kids, the players he'd recently coached at the Rams: Deacon, Lamar, Roman, and Jack. Deacon Jones, Lamar Lundy, Roman Gabriel, and Jack Pardee had organized a team strike against Dan Reeves the day after Reeves had fired Dad. Thirty-eight of the Rams' forty players signed a petition saying they would quit if my father was not rehired as head coach. "We won't play if George don't coach" was the slogan they chanted for the television cameras. Dad was so moved by this display of support that he could barely manage more than a few words for the reporters before stepping down off the platform to lean against the shoulders of his men. Dark sunglasses covered his eyes as one by one the players took the microphone to speak for their former coach, whom some called their best friend.

"Now, those are men to aspire to," our dad told us. "You kids need something to aspire to." He said television was turning us all into wallpaper. He said we needed to have daily goals besides watching television all day long. "Show me a person without goals and I'll show you someone who's dead!"

"Please, George," Mom said, "it's New Year's Eve. Can we please eat a dinner in peace?"

But my father now directed his gaze at the little black-and-white television perched on a stool over my shoulder. A local Los Angeles announcer was summarizing the past year's events: the assassinations of Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the recent firing of Los Angeles Rams Head Coach George Allen.

"You know," my father said, not taking his eyes off the television, "I'm disappointed in each of you kids." He said there was a lot to be done around the new house and no one was doing anything about it. A few weeks earlier, we had moved into our large new house. It was our third home in three years as we followed Dad, moving from team to team in the NFL. Sealed boxes still filled every room of the house. Pointing to a box in the kitchen, Dad said, "You see a box like that, you unpack it!" Pointing to a scrap of brown paper on the floor, he said, "You see a piece of paper, you pick it up!" Peeling away a strip of packing tape stuck to the edge of the kitchen table, Dad said, "You see a piece of tape, you toss it out!"

We leapt from our dinner chairs to unpack boxes, pick up paper, toss out tape.

Mom stopped us all. "Not now," she said. "Sit down, it's time to eat. Let's eat."

"You know," Dad said, "it would be nice if someone said a little grace for a change."

"I said it last time," my oldest brother, George, said.

"I said it last time," my middle brother, Gregory, said.

"Bull, you did," my youngest brother, Bruce, said. "I always say it!"

"Grace!" Mom shouted. "There. I said it."

Dad shook his head. "Boy, oh, boy," he said, "here I am fighting to get back my job, and my own family cannot even bow their heads to say a few prayers."

Everyone looked to me. I was almost eight years old. When no one else wanted to say grace, I said it. I bowed my head and closed my eyes and thanked the Lord for our food and shelter and asked the Lord to help Dad get his job back with the Rams.

"Amen," we all said together, and Dad thanked me for my special grace, and George called me Ugly and I called George a Moron and George called me a Dog and I told George to Shut Up and my father said, "You know I don't like that word," and Gregory said, "What word?" and Bruce screamed, "Shut up!" and Dad just shook his head, ran his hand through his thick black hair, and said, "Boy, oh, boy, you kids."

"Now can we eat?" my mother said.

"Who's stopping you?" my father said. His gaze returned to the television. The announcer was now giving a play-by-play of Senator Robert Kennedy's assassination in the kitchen of the Los Angeles Ambassador Hotel.

"Now there's a leader," Dad said. "There's a man this country will never forget."

My father was talking about Rosey Grier, a former Rams defensive lineman who had tackled and helped capture Kennedy's assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, moments after the shooting.

The telephone rang.

"Uh-oh!" said Dad, sitting up. "Uh-oh!" meant "Oh, no!" Every time the telephone rang since Dan Reeves called the day after Christmas to say, "Merry Christmas, George, you're fired," my father would say, "Uh-oh!" and refuse to answer the telephone. We knew the call would invariably be for Dad, but still we all sprang to answer it, saying, "Hello? Allen residence? Hello?" and then we would force the receiver into our father's hand. It would usually be just another sports reporter calling to ask Dad about his "uncertain future." Our number was unlisted, yet every sportswriter in the country seemed to have it in his Rolodex.

Earlier that day, our mother, who is French, had intercepted one such call.

"You Americans are so brutal!" she laid into the guy, "so different from the French. At least when a man is standing at the guillotine, we give him a cigarette before cutting off his goddamn head!"

Mom hated reporters. She said reporters were vultures preying on Dad. Dad liked reporters. He often talked to them as if they were long-lost friends, confiding in them recently how much he loved coaching the Rams. That's all Dad wanted, he would tell reporters. Dad would tell them, "I just want to coach, you see?" But this time, tonight, when the telephone rang, Mom answered it. Enough!" she screamed into the receiver and slammed it down, then took it off the hook.

"You think those goddamn reporters care if we're trying to eat our goddamn holiday dinner in peace?" she asked. I looked around the table. Gregory was pouring himself another glass of milk, Bruce was slurping up the last of a long spaghetti strand, and George was licking his plate clean.

Dad hadn't touched his food.

"Starving yourself isn't going to get your job back, so eat," she said. Then she said to all of us, "Your father thinks chewing is a distraction. Your father's afraid chewing might take his mind off football."

Dad nodded his head and sipped his milk. He'd lost fifteen pounds during the last season: skipping meals, getting vitamin shots, drinking milk for dinner. He had two bleeding stomach ulcers: one that acted up during the season and one that bled off-season. He believed milk calmed ulcers. His love of milk was so well known that he became the spokesman for a local dairy that sponsored his weekly pregame radio show. Instead of regular payment, Dad made a deal with the dairy to deliver hundreds of gallons of the stuff to our door daily.

"You know, football was the only thing that didn't bug me," our father said. I knew of a few things that did bug him, beginning with his childhood during the Depression in Detroit, where he and his parents and sister lived in a two-room shack with a single-seat outhouse. His father, Earl, a failed musician, suffered a severe injury on the Ford assembly line that left him with a metal plate in his head and shakes so violent that even alcohol could not sedate his pain. After that, Earl could not keep a job. At ten years old, my father went to work to support the family by planting potatoes for pennies a day. What really bugged my father was allowing his brilliant younger sister, Virginia, to convince him that she should take over the care of their aging parents so that he could pursue his dream of coaching professional football. Only in later years did he realize the depth of her sacrifice when he discovered she had hidden the menial nature of her clerical work in order to allow her brother his rise to fame. These were some of the things that bugged my father.

From the Hardcover edition.

Dad sat at the dinner table, sipping his milk. We all watched him sip his milk, his first and only drink of choice. Then he set his glass down on the table where my three older brothers and I sat, while Mom scowled as she stirred a pot of boiling spaghetti on the kitchen stove.

"Listen," Dad said, "a guy who goes out after a loss and parties is a two-time loser." Dad was referring to his ex-boss, Los Angeles Rams owner Dan Reeves. "First, he's a loser for losing, and second, he's a loser for thinking he doesn't look like a loser by partying it up."

Dan Reeves had once said, "I'd rather lose with a coach I can drink with and have fun with than win with George Allen." Reeves had been drinking all Christmas night at a Hollywood bar when he called my father at home from the bar telephone, the following day, at 8 a.m. "Merry Christmas, George," Reeves had said. "You're fired!"

That was a week ago. Now, on New Year's Eve, Dad sat in his pajamas, talking to us kids at the dinner table. Mom stood in her bathrobe, clanging pots and pans on the stove. This was a rare dinner with Dad since he had taken the job as head coach of the Los Angeles Rams three years before. For my father, getting the Rams to the National Football League Championship meant drinking a tall glass of milk at the office for dinner, then spending the night on his office couch so that he wouldn't waste valuable work time driving home, eating with his family, and sleeping with his wife. The long hours paid off: the 1968 Rams defense had set a new fourteen-game record for fewest yards allowed on offense. But the team finished second in the Coastal Division, falling two games short of reaching the championship play-offs. A week later, Dan Reeves fired Dad. Since then, we had been keeping the TV volume turned down low so as not to disturb Dad's weeklong monologue, which had begun the day after Christmas.

"Heck," Dad said, "Dan Reeves is dying of cancer. Maybe that's his problem. He's drinking to forget he's alive!"

We all knew what came next. When talking about drinking and dying, our father always cited his own father, Earl, who died an unemployed alcoholic. To our father, the only thing worse than losing was dying without a job. "I want to die working," Dad told us all. "That's the only way to die!"

"Dying," Mom said, setting down Dad's plate of spaghetti. "Who's talking about dying? I thought we were going to have a nice dinner together for once in our lives."

"I'm trying to teach these kids a lesson."

"They've learned enough as it is."

"You know," our father said as our mother finished serving dinner, "you kids have a lot to learn about life."

We kids nodded. We twisted our forks into our spaghetti as Dad told us again about his other kids, the players he'd recently coached at the Rams: Deacon, Lamar, Roman, and Jack. Deacon Jones, Lamar Lundy, Roman Gabriel, and Jack Pardee had organized a team strike against Dan Reeves the day after Reeves had fired Dad. Thirty-eight of the Rams' forty players signed a petition saying they would quit if my father was not rehired as head coach. "We won't play if George don't coach" was the slogan they chanted for the television cameras. Dad was so moved by this display of support that he could barely manage more than a few words for the reporters before stepping down off the platform to lean against the shoulders of his men. Dark sunglasses covered his eyes as one by one the players took the microphone to speak for their former coach, whom some called their best friend.

"Now, those are men to aspire to," our dad told us. "You kids need something to aspire to." He said television was turning us all into wallpaper. He said we needed to have daily goals besides watching television all day long. "Show me a person without goals and I'll show you someone who's dead!"

"Please, George," Mom said, "it's New Year's Eve. Can we please eat a dinner in peace?"

But my father now directed his gaze at the little black-and-white television perched on a stool over my shoulder. A local Los Angeles announcer was summarizing the past year's events: the assassinations of Senator Robert F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the recent firing of Los Angeles Rams Head Coach George Allen.

"You know," my father said, not taking his eyes off the television, "I'm disappointed in each of you kids." He said there was a lot to be done around the new house and no one was doing anything about it. A few weeks earlier, we had moved into our large new house. It was our third home in three years as we followed Dad, moving from team to team in the NFL. Sealed boxes still filled every room of the house. Pointing to a box in the kitchen, Dad said, "You see a box like that, you unpack it!" Pointing to a scrap of brown paper on the floor, he said, "You see a piece of paper, you pick it up!" Peeling away a strip of packing tape stuck to the edge of the kitchen table, Dad said, "You see a piece of tape, you toss it out!"

We leapt from our dinner chairs to unpack boxes, pick up paper, toss out tape.

Mom stopped us all. "Not now," she said. "Sit down, it's time to eat. Let's eat."

"You know," Dad said, "it would be nice if someone said a little grace for a change."

"I said it last time," my oldest brother, George, said.

"I said it last time," my middle brother, Gregory, said.

"Bull, you did," my youngest brother, Bruce, said. "I always say it!"

"Grace!" Mom shouted. "There. I said it."

Dad shook his head. "Boy, oh, boy," he said, "here I am fighting to get back my job, and my own family cannot even bow their heads to say a few prayers."

Everyone looked to me. I was almost eight years old. When no one else wanted to say grace, I said it. I bowed my head and closed my eyes and thanked the Lord for our food and shelter and asked the Lord to help Dad get his job back with the Rams.

"Amen," we all said together, and Dad thanked me for my special grace, and George called me Ugly and I called George a Moron and George called me a Dog and I told George to Shut Up and my father said, "You know I don't like that word," and Gregory said, "What word?" and Bruce screamed, "Shut up!" and Dad just shook his head, ran his hand through his thick black hair, and said, "Boy, oh, boy, you kids."

"Now can we eat?" my mother said.

"Who's stopping you?" my father said. His gaze returned to the television. The announcer was now giving a play-by-play of Senator Robert Kennedy's assassination in the kitchen of the Los Angeles Ambassador Hotel.

"Now there's a leader," Dad said. "There's a man this country will never forget."

My father was talking about Rosey Grier, a former Rams defensive lineman who had tackled and helped capture Kennedy's assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, moments after the shooting.

The telephone rang.

"Uh-oh!" said Dad, sitting up. "Uh-oh!" meant "Oh, no!" Every time the telephone rang since Dan Reeves called the day after Christmas to say, "Merry Christmas, George, you're fired," my father would say, "Uh-oh!" and refuse to answer the telephone. We knew the call would invariably be for Dad, but still we all sprang to answer it, saying, "Hello? Allen residence? Hello?" and then we would force the receiver into our father's hand. It would usually be just another sports reporter calling to ask Dad about his "uncertain future." Our number was unlisted, yet every sportswriter in the country seemed to have it in his Rolodex.

Earlier that day, our mother, who is French, had intercepted one such call.

"You Americans are so brutal!" she laid into the guy, "so different from the French. At least when a man is standing at the guillotine, we give him a cigarette before cutting off his goddamn head!"

Mom hated reporters. She said reporters were vultures preying on Dad. Dad liked reporters. He often talked to them as if they were long-lost friends, confiding in them recently how much he loved coaching the Rams. That's all Dad wanted, he would tell reporters. Dad would tell them, "I just want to coach, you see?" But this time, tonight, when the telephone rang, Mom answered it. Enough!" she screamed into the receiver and slammed it down, then took it off the hook.

"You think those goddamn reporters care if we're trying to eat our goddamn holiday dinner in peace?" she asked. I looked around the table. Gregory was pouring himself another glass of milk, Bruce was slurping up the last of a long spaghetti strand, and George was licking his plate clean.

Dad hadn't touched his food.

"Starving yourself isn't going to get your job back, so eat," she said. Then she said to all of us, "Your father thinks chewing is a distraction. Your father's afraid chewing might take his mind off football."

Dad nodded his head and sipped his milk. He'd lost fifteen pounds during the last season: skipping meals, getting vitamin shots, drinking milk for dinner. He had two bleeding stomach ulcers: one that acted up during the season and one that bled off-season. He believed milk calmed ulcers. His love of milk was so well known that he became the spokesman for a local dairy that sponsored his weekly pregame radio show. Instead of regular payment, Dad made a deal with the dairy to deliver hundreds of gallons of the stuff to our door daily.

"You know, football was the only thing that didn't bug me," our father said. I knew of a few things that did bug him, beginning with his childhood during the Depression in Detroit, where he and his parents and sister lived in a two-room shack with a single-seat outhouse. His father, Earl, a failed musician, suffered a severe injury on the Ford assembly line that left him with a metal plate in his head and shakes so violent that even alcohol could not sedate his pain. After that, Earl could not keep a job. At ten years old, my father went to work to support the family by planting potatoes for pennies a day. What really bugged my father was allowing his brilliant younger sister, Virginia, to convince him that she should take over the care of their aging parents so that he could pursue his dream of coaching professional football. Only in later years did he realize the depth of her sacrifice when he discovered she had hidden the menial nature of her clerical work in order to allow her brother his rise to fame. These were some of the things that bugged my father.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

Advance praise for Fifth Quarter

"Fifth Quarter is the best book about football I've ever read--and Jennifer Allen never played a down in her life. But she was born to be a writer, she grew up around some of the greatest names in the NFL, and her father happened to be one of the greatest coaches in history. What a family this woman hails from!"

--Pat Conroy

"What an extraordinary story! Within a terrifying, pathetic, and sometimes-- inevitably--hilarious tale of professional football and her father's life as a coach, Jennifer Allen shows everything that's wrong--and right--about 'sports-minded' American men."

--Carolyn See

From the Hardcover edition.

"Fifth Quarter is the best book about football I've ever read--and Jennifer Allen never played a down in her life. But she was born to be a writer, she grew up around some of the greatest names in the NFL, and her father happened to be one of the greatest coaches in history. What a family this woman hails from!"

--Pat Conroy

"What an extraordinary story! Within a terrifying, pathetic, and sometimes-- inevitably--hilarious tale of professional football and her father's life as a coach, Jennifer Allen shows everything that's wrong--and right--about 'sports-minded' American men."

--Carolyn See

From the Hardcover edition.