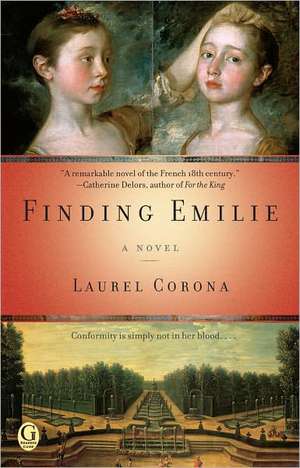

Finding Emilie

Autor Laurel Coronaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 apr 2011

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

San Diego Book Awards (2012)

Lili du Châtelet yearns to know more about her mother, the brilliant French mathematician Emilie. But the shrouded details of Emilie’s unconventional life—and her sudden death—are elusive. Caught between the confines of a convent upbringing and the intrigues of the Versailles court, Lili blossoms under the care of a Parisian salonnière as she absorbs the excitement of the Enlightenment, even as the scandalous shadow of her mother’s past haunts her and puts her on her own path of self-discovery.

Laurel Corona’s breathtaking new novel, set on the eve of the French Revolution, vividly illuminates the tensions of the times, and the dangerous dance between the need to conform and the desire to chart one’s own destiny and journey of the heart.

Preț: 152.84 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 229

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.25€ • 30.53$ • 24.20£

29.25€ • 30.53$ • 24.20£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781439197660

ISBN-10: 1439197660

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 135 x 210 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Original.

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

ISBN-10: 1439197660

Pagini: 448

Dimensiuni: 135 x 210 x 33 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:Original.

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Extras

1759

“STOP WINNING all the time!” Delphine tossed her cards in the air in frustration that turned to laughter as they cascaded over Lili’s head and fell around her on the bed. The two ten-year-old girls sat cross-legged in muslin nightdresses, curling their bare toes around ripples in the green velvet coverlet. Next to them, a small white dog snorted at the disturbance to his sleep.

Lili picked up the strewn cards and tapped the sides of the pack until they were aligned. “Want to play again? I told you how I do it.”

Delphine sighed. “I know. You remember the cards we’ve already played. Me, it’s king, queen, la-la-la.”

“Well, you can’t win at piquet if you don’t know what’s already happened.”

“All of that remembering is like schoolwork. No more fun than doing sums.” Delphine stood up on the bed behind Lili. “Want me to play with your hair? I’ll get some combs and put it up just like Madame de Pompadour’s.” She picked up Lili’s brown hair and crushed it in her hands on top of Lili’s head. “Just like that,” she said, pursing her lips and kissing the air in imitation of King Louis XV’s mistress. “Where did you put your brush?”

Lili didn’t answer. “They’re arguing about something downstairs,” she said, cocking her head. “Can you hear them?”

Delphine sniffed as she retrieved the brush from Lili’s dressing table. “Who cares? Silly old men.” While her back was turned, Lili hopped off the bed and tiptoed out into the upstairs hallway of Hôtel Bercy. The dog jumped down to follow her.

“Stanislas-Adélaïde! Come back here!” she heard Delphine scold. “You’re practically naked!” Lili turned and put her finger to her lips. “I’m going to try to listen.”

“Well, at least put on your robe! I can see the outline of your bottom under your chemise!” Ignored, Delphine gave a dramatic sigh and, throwing on her dressing gown, came out into the hallway. “It’s freezing,” she whispered, picking up the tiny bichon frise and holding it to her chest. “Look! Tintin is shivering, even with his fur coat.” She nuzzled him. “Aren’t you, mon petit?”

“Shh!” Lili held a finger to her lips. “They’re talking about the Jansenists, I think. Or maybe it’s the Jesuits. It’s hard to hear.” Lili stood by the railing at the top of the staircase and cocked one ear. “I thought I heard someone call Jesuits a plague on France, but that can’t be right.” She listened again. “Or maybe it was that there’s no place for them in France, but that doesn’t make much sense either.” She looked at Delphine. “They’re priests. How could anyone think there’s no need for priests?”

“You’ll need one soon enough if you catch your death of cold,” Delphine said, prancing on her bare toes. “My feet are turning to ice.”

The voices downstairs had quieted again to an indistinguishable murmur. Lili suddenly became aware of floorboards so cold they burned her toes and sent goose bumps up her arms and legs. “Race you to bed!” she said with a grin as she dashed past Delphine. The two girls leapt onto the soft pile of bedcovers, and Tintin joined in the jumble of arms and legs, licking their eyes and noses until they squealed.

“Time for your hair,” Delphine reminded her. Lili sat up, with Tintin in her lap, and Delphine knelt behind her. Lili closed her brown eyes in contentment as Delphine brushed her hair, but Lili’s ears remained focused on the murmuring downstairs. “I’d like to know what they’re so passionate about, wouldn’t you?”

“Who?”

“The men at Maman’s salon.”

“Unless it’s about me, I don’t really care,” Delphine said. She sat back on her haunches. “It would be rather nice to be Maman, wouldn’t it? So beautiful and kind that everyone comes to her salon because they’re secretly in love with her.”

She crawled around in front of Lili, shooed the dog away, and laid her head in Lili’s lap. “My arm’s tired. Tell me a story,” she pleaded. “About a beautiful princess. I don’t care which one.”

“Don’t you get tired of those? How about ‘Puss and Boots,’ or something else for a change?”

Delphine glared at her and said nothing.

“All right,” Lili conceded. “If you promise that just one will put you to sleep.”

“Promise.”

Lili took a deep breath. “Once upon a time …”

Corinne, the girls’ femme de chambre, gave a cursory knock on the door frame before coming in. “I beg your pardon, mam’selles,” the young servant said with a quick curtsey. “Madame said I am to make sure you have a good sleep before you return to the abbey tomorrow.” She went to the table and extinguished an oil lamp. “Madame says that you may sleep in one bed if you wish.”

With a groan of annoyance, Lili wiggled out from under Delphine’s head and lay down beside her. When Corinne had arranged the covers over them, she blew out the candles, and shut the door behind her. Lili immediately sat back up in the dark, and Delphine resumed her position on her lap.

“Once upon a time there was a king and queen who had no children for years and years. Finally they had a baby daughter, and they asked seven fairies to be the godmothers. But they forgot about one fairy, who was so old she rarely left her tower.”

“An ugly fairy,” Delphine murmured. “With one good eye.”

“Mmm. When she arrived and saw there was no place for her at the christening banquet, she was angry, and she cursed the baby girl to die of a spindle prick before she could be married …” Lili stroked Delphine’s forehead. “Sleepy yet?”

“Of course not. You barely started. But skip to the part about the dresses she wore.”

“Let’s say the princess was called …” Lili pretended to be choosing a name before coming up with the same answer she always did. “Princess Delphine.” Delphine sighed her approval and wiggled deeper into Lili’s lap. “A new dress magically appeared for her every morning, and her petticoats left a trail of sparkles behind her.”

“Sparkles?”

“Well, they are magic dresses,” Lili said. “Do you like it?”

“Oh yes,” Delphine whispered. “Put the sparkles in every time.”

“One day the beautiful princess was wandering through the palace and she saw an old woman spinning …”

By the time Lili reached the point where Sleeping Beauty was awakened from a hundred-year sleep, Delphine’s breathing was shallow, and her head was heavy on Lili’s lap. “The prince noticed right away that her gown was hopelessly out of style,” Lili continued. “Even his grandmother would not have been seen in public wearing it.” If Delphine were awake, they would have added detail after ugly detail to the dress, but her breathing did not change. “So the wolf went to the grandmother’s house and tricked the little girl into getting into bed with him. Then he ate her up, and they all lived happily ever after.” Lili waited a few seconds before transferring Delphine’s head to a pillow and snuggling in next to her.

She heard the voices of two departing guests and the sound of horses’ hooves in the street just beyond the courtyard of Hôtel Bercy. What could they care enough to argue about week after week? Certainly not fairy stories, or anything she and Delphine were taught at the convent. Tintin snored softly next to her, and Delphine murmured something in her sleep. Lili yawned and put her arm around her, and let her thoughts drift off into nothing.

* * *

A SPRING THUNDERSTORM had drenched the city overnight. The next morning Corinne held up the backs of Lili’s and Delphine’s skirts to avoid muddying their hems in the few steps to the carriage, and sent them off before Maman was awake. The sky was clearing, but one gray cloud after another drifted in front of the sun, darkening the coach bearing the two girls down the Rue Saint-Antoine toward the center of Paris.

Wrapped in the gloom that always overcame them on these mornings, neither girl said a word as the carriage made its way between the narrow rows of shops and houses lining the Pont Notre-Dame, and then rattled across the Île de la Cité and the Petit Pont to the far side of the Seine. Though their private room at the Abbaye de Panthémont was furnished at Maman’s expense with soft bedcovers and a thick rug on the floor, life at home was as cozy as the thick warm chocolat and fresh-baked brioche they had eaten for breakfast that morning. Being at Hôtel Bercy meant not having to get up for prayers and going to sleep only when Maman remembered to send Corinne. It meant being asked what they would like for supper, and having a dog that would beg and roll over for the tiniest scrap smuggled from the dining room.

Delphine sniffled. “I hate Sister Thérèse.” After a moment she added, “But not as much as I hate Sister Jeanne-Bertrand.” Lili was silent, and Delphine went on. “I can’t do anything well enough for them.” She pinched her nostrils. “‘Ladies don’t get ink on their fingers when they write,’” she said in an imitation of Sister Jeanne-Bertrand so perfect that Lili giggled in spite of her dark mood.

In Rue Saint André-des-Arts, the coach slowed to a stop. Obstructions in the streets were common enough that Delphine took no note. “‘A lady’s quality can be seen in the way she signs her name,’” she continued in the same nasal tone. “‘Your handwriting is getting bigger. It must be all the same size, or you must start again.’”

Hearing the voices of a group of children in the narrow, unpaved street, Lili pulled back the curtain and peered out. Her eyes locked on a young man in a threadbare coat, but sporting a new hat in the latest style. He was swinging his walking stick at a group of ragged children, while one of them dangled just out of reach a book-size parcel tied with string.

“Give it back!” he shouted, as another boy with a dirty face and unkempt hair made a grab for the man’s coat pocket. Two women in shabby dresses and soiled white caps watched the commotion from the doorway of a bakery, with no more interest than if they were watching birds peck for crumbs. Another passerby, older and slightly better dressed, grabbed one of the children and shoved him to the ground.

“Street scum!” he hissed, kicking the boy over and over again. “Get out of here before I knock your rotten little teeth out!” Neither woman made any move to intervene, but one of them shook a fist. “Leave him alone!” she said. “Can’t you see he’s got nothing in this world, and you so rich and all?”

The boy holding the parcel grinned and cocked his head as he danced backward down the street, and the others who had escaped the man’s wrath followed slowly enough to convey they were not frightened in the least by anyone or anything. Lili’s carriage started forward with a lurch, just as another coach passed in the other direction and sprayed thick, black mud onto the window where her face was pressed. Startled, Lili sat back, but she immediately leaned forward again to look out through the one spot that was not covered with slime. Splattered black from head to toe, including the new hat, the two men waved their fists in the air, cursing the world.

Lili giggled for a moment, before pressing her gloved fingers to her mouth so Delphine wouldn’t notice. She was sure to turn the men’s misfortune into something to joke about, and what happened really wasn’t funny. The carriage had barely moved before stopping again, and Lili craned her neck to keep watching. The boy had gotten up and was now walking in their direction, showing no signs at all that he had just been kicked repeatedly in the ribs. He had his hands in his pockets and under his muddy cap he was grinning and bobbing his head as if he might be humming a tune.

He stopped for a moment to make sure the older man wasn’t watching and then pulled a gold watch from his pocket. As he brushed a spot of mud from its surface, he looked up and saw Lili watching him from the carriage. With a smirk, he swung it by the fob for a moment just to make sure she saw. Then he stuck out his tongue and ran down an alley before the man had a chance to notice his pocket had been picked.

ALONG THE RUE de Grenelle, the tight squeeze of buildings and narrow streets gave way to more stately buildings and patches of tidy gardens as the street left the city and became a country road connecting the farming village of Grenelle with Paris. Just before the grounds of Les Invalides, the coach pulled up at the Abbaye de Panthémont. A porter and a young novice emerged from the imposing stone building, and the girls and their belongings were whisked inside.

Despite the chill lingering in the walls, the fire was unlit, as it was May. Lili unwrapped the copy of Madame d’Aulnoy’s fairy tales she had brought from home. She opened it to the place she had left off, marked by a ribbon between the pages. “I wish I could stay here and read,” she said, looking at the engraving of the sad and ragged princess Finette Cendron.

Delphine sighed as she unlaced her boots. Shivering in the musty cold, they changed out of their traveling clothes and into the simple dresses that were the uniform of the convent, before going out into the hallway.

“Time to say hello to Mother-Ugly,” Delphine whispered softly enough not to be overheard. At one point in her life, Abbess MarieCatherine had lost an eye, and though the embroidered black velvet patch she wore was tasteful, a one-eyed nun was enough to warrant horror, if not abject fear.

“Do you think she used to be a pirate?” Delphine had asked when they were eight and saw her for the first time.

“I’m quite sure not,” Lili had said. “Maybe she was born that way. Maybe she had a tiny eye patch even then. A pretty white one to match her christening bonnet.”

Delphine’s eyes were huge. “Do you really think so?”

“Maybe a raven pecked her eye out,” Lili went on. “You know, like the birds who ate Prometheus’s liver.”

“Over and over again,” Delphine shuddered. She thought for a moment. “Do you think perhaps she was supposed to be born a Cyclops and some goddess had mercy on her and softened the curse?”

“Or maybe an evil wanderer in the streets of the Faubourg Saint-Germain scooped it out with a spoon.”

Lili knew she had gone too far when she saw Delphine’s face. “Things like that can’t happen to us, can they?” Delphine had whimpered.

Lili rushed to reassure her that she just liked to make things up, and Delphine forced her to promise never to invent anything that involved people who might actually live in Paris.

A few minutes later, the two made the short visit required of returning girls, and before being turned away by a servant, they caught a glimpse of the abbess without her patch. Over the hollow cavity, her lids had been sewn together, and the scars formed what looked like stubby white eyelashes. The girls backed away in shock and ran to their room, where Delphine vomited into a washbasin and Lili retched in sympathetic dry heaves until her stomach was sore.

Still, Lili told Delphine later, when she had a chance to think about it some more, it wasn’t fair to blame the abbess, because it was hard to imagine how losing an eye was her fault.

“I know,” Delphine said, “but still, there should be something she can do not to bother people so much.”

“Perhaps she could wear a hood that covered her whole face, with one hole for her good eye,” Lili suggested. She meant it as a joke, but Delphine took all solutions seriously, including wearing shimmering veils like a harem girl, until Lili pointed out how unlikely that would be for a nun.

Finally Delphine dismissed the entire subject. “All I know is I would never let that happen to me,” she said, touching each of her eyes tenderly. “I’d die first, wouldn’t you?”

Wondering for a moment if losing an eye might give someone a secret, compensatory magic, Lili didn’t respond. Maybe that’s the real reason the abbess is so frightening, she thought. She has a power we don’t even know about. “I think I’d have to wait and see,” she finally replied. “It’s probably a good idea to wait to see how desperate you really are.”

THE AFTERNOON OF their return to the abbey, Lili and Delphine went with a few other girls to a wood-paneled study with large windows giving out onto a lawn bordered with tidy flowers and neatly clipped hedges. Sister Thérèse, their catechism nun, was leafing through one of the leather-bound books in an ornately carved bookcase.

“Good afternoon, madame,” each girl said before taking her place on one of the couches arranged around a fireplace.

“Bien,” the middle-aged nun said, coming over to her chair without sitting down. “Shall we pray?” The girls all stood up and crossed themselves, and Lili heard Delphine suppress a burp from their just-completed midday meal. “in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Amen,” they murmured before droning an Ave Maria and a Pater Noster. Sister Thérèse gestured to them to sit down, and after she was settled in an armchair facing them, she opened her book.

“Today is the feast day of Saint Solange,” she said, looking over the top of her spectacles at the girls. “Would anyone like to tell us who this blessed martyr was?”

Delphine straightened her back so quickly that Lili thought she might fly off the chair. “She was a shepherdess on the estate of the Comte of Poitiers, who had an evil son,” Delphine blurted out, and though her feet were hidden under her skirt, she jiggled them so intensely that Lili felt the motion against her own thigh.

“Young ladies, wait to be called upon,” the nun said. “And don’t speak so quickly. It isn’t becoming to sound so excited.”

“Oui, Sister Thérèse,” Delphine said, looking down at her lap. “Saint Solange took a vow of chastity because she was so devoted to God and when the count’s horrid son Bernard tried to—tried to—”

“Tried to force himself on her,” the nun prompted.

“Oui, Sister Thérèse. When he tried to do that, she resisted him with all her might, so he killed her.”

Sister Thérèse frowned. “Does someone else feel they can tell the story with the dignity it warrants?”

Lili felt Delphine sit back in surprise, and knew that back in their room she would be in tears. “What did I do wrong?” she would ask. “Didn’t I know the story? Didn’t I care enough about that stupid saint?”

“Mademoiselle de Praslin,” the nun said, “would you be so kind as to say what happened, and do so with the proper demeanor for a lady?”

Delphine pushed her hand down in the space between her skirt and Lili’s. Lili’s hand followed, and squeezing their interlaced fingers, they stared at the floor while Anne-Mathilde de Praslin spoke. Anne-Mathilde was the daughter of the Duc de Praslin, one of the richest and most powerful men in France. At twelve, she was two years older than Lili and Delphine, and her body was beginning to take on the curves of a woman. Her hair was pale gold and her skin, a radiant ivory, was so lacking in flaws it seemed to be made of something other than flesh. “A perfect beauty,” Lili had overheard one of the nuns remarking. “A bride worthy of a great noble of France.” If Delphine hated Sister Thérèse, she truly loathed Anne-Mathilde—a sentiment she could count on Lili to embellish in the darkness of their room.

“Bernard tried a number of times to grab Solange and force her to the ground,” Anne-Mathilde said in a deliberately musical voice, casting a gloating look at Delphine that only Lili saw. “But Solange prayed to the Blessed Virgin, who gave her the strength to fight him off. He was angry, not just because he couldn’t have her, but because she had embarrassed him in front of his friends.”

Anne-Mathilde’s best friend, Joséphine de Maurepas, nodded. “If I may add a detail,” she said in a voice so simpering, it was all Lili could do not to grab the girl’s hair and twist it until she squealed. Joséphine was also twelve, like Anne-Mathilde, but so scrawny it was hard to imagine she would ever look like anything but a little girl. The drab ash-brown of Josephine’s hair and the way she scurried around in thrall of her best friend made Lili think of the little mice she’d watched the scullery maids shoo away with a broom at home.

“I’d like to remind everyone that Bernard fell off his horse once trying to reach down and pull Solange onto it,” Joséphine was saying. “To fall off a horse for a peasant girl …?” Her voice curled up, as if she were asking whether anyone in the room really needed her to explain the disgrace.

Sister Thérèse gave them each a nod of approval. “And now, Stanislas-Adélaïde,” she said, her eyes narrowing, “will you finish the story for us?”

I should have known Sister Thérèse would do this, Lili thought. Delphine had been ridiculed, and now Lili had to retell the part of the story Delphine relished most. Lili withdrew her hand and brushed her ear, the secret signal with which she and Delphine warned each other to keep a straight face regardless of what was said next.

“I can certainly do that, Sister Thérèse,” Lili said, copying Anne-Mathilde and Joséphine’s unctuous tone. “Because at home Mademoiselle de Bercy and I often discuss the important message about piety the story contains for girls our age.” A lie is a small sin, she thought, especially for Delphine. “However, I find it particularly edifying to hear Delphine tell it, and I believe the others have not had that opportunity. May I ask if she might be permitted to finish the story herself?”

Lili heard the rustling of Anne-Mathilde’s and Joséphine’s dresses and knew without looking that their faces were shining with anticipation of something new to disparage. Sister Thérèse stared at Lili for a moment before she spoke. “If Mademoiselle feels she can control her urge to tell it so breathlessly?” Her eyebrows arched as she turned to Delphine.

“Bernard beheaded her,” Delphine said. “But even with her head on the ground, she was able to invoke the name of God three times.” Though Delphine may have sounded demure and ladylike, Lili recognized the discouragement in her tone. At home, away from the nuns’ disapproval, Delphine would have stood up and tapped her shoulders and neck with her hands, as if surprised to realize that her head was no longer there. “Mon Dieu,” she would have said in a loud voice, before repeating it more plaintively as she crumpled to the floor. “Mon Dieu,” she would have whispered a third time, tapping the floor like a blind person until she found her head and picked it up.

“Then Solange walked into the town,” Lili heard Delphine say. “It wasn’t until she reached the church that she fell to the ground and died.”

“May God’s holy name be praised,” Sister Thérèse murmured, and everyone made the sign of the cross.

“Did I do better?” Delphine asked, her voice rising in hope of at least faint praise.

“It was an improvement,” the nun said. “But it isn’t seemly for a young lady to beg for approval.” Anne-Mathilde and Joséphine stifled a giggle behind their hands.

“I understand,” Delphine said. Lili could hear the tremor in Delphine’s voice. “I want nothing more than to improve myself,” Delphine added. Lili looked to see if she was touching her ear, but she wasn’t.

“And with God’s grace, you will succeed, my child,” Sister Thérèse said. “With God’s grace, and with faith, anything is possible.” She crossed herself. “After all, look at our blessed Saint Solange.”

“Oui, Sister Thérèse.” Out of the corner of her eye, Lili saw Delphine cross herself. She rushed to do the same, but so quickly that she did it again, just to make sure it counted.

DELPHINE’S TEARS GAVE way to exhausted sniffles and then to light snoring in their room that night. The candle was still lit, and Lili picked up her book of fairy tales to read until her mind was quiet enough for sleep.

“Once upon a time there was a king and queen who ruled so badly they lost their kingdom, and they and their three daughters were reduced to day labor.” The story of Finette Cendron was one of Lili’s favorites, but tonight none of the stories in the book was likely to amuse her.

She went to the desk and took out a sheet of paper already nearly full of penmanship exercises. I could try writing a story myself, she thought. She touched the tip of a quill in the inkwell on the desk. Then, squinting to focus in the dim light, she began.

“Once upon a time …”

Once upon a time what? She thought for a moment, and suddenly it came to her.

“Once upon a time, there was a girl living in a dreary village who wanted nothing more than to travel to the stars. Her name was …”

Lili thought for a moment. She could call her Delphine and put some dresses in the story, but she didn’t want to do that. She scratched out the last three words and dipped her quill again.

“Meadowlark had a laugh like a songbird, so everybody called her Meadowlark. Every night Meadowlark would sneak outside and hope with all her might that her wish could come true. And then, to her surprise, one night a horse made of starlight appeared in front of her. ‘Are you the girl named Meadowlark?’ the horse asked. When she said yes, the horse snorted and reared up. ‘My name is Comète,’ it said. ‘Climb on my back.’ Before she knew it, Comète had galloped off with her into the night sky, leaving behind a trail of stars wherever its hooves touched.”

Lili’s eyes ached in the flickering candlelight. She would have to stop. Dipping her pen one more time, she wrote in big letters at the top of the page, “Meadowlark, by S.-A. du Châtelet.”

© 2011 Laurel corona

“STOP WINNING all the time!” Delphine tossed her cards in the air in frustration that turned to laughter as they cascaded over Lili’s head and fell around her on the bed. The two ten-year-old girls sat cross-legged in muslin nightdresses, curling their bare toes around ripples in the green velvet coverlet. Next to them, a small white dog snorted at the disturbance to his sleep.

Lili picked up the strewn cards and tapped the sides of the pack until they were aligned. “Want to play again? I told you how I do it.”

Delphine sighed. “I know. You remember the cards we’ve already played. Me, it’s king, queen, la-la-la.”

“Well, you can’t win at piquet if you don’t know what’s already happened.”

“All of that remembering is like schoolwork. No more fun than doing sums.” Delphine stood up on the bed behind Lili. “Want me to play with your hair? I’ll get some combs and put it up just like Madame de Pompadour’s.” She picked up Lili’s brown hair and crushed it in her hands on top of Lili’s head. “Just like that,” she said, pursing her lips and kissing the air in imitation of King Louis XV’s mistress. “Where did you put your brush?”

Lili didn’t answer. “They’re arguing about something downstairs,” she said, cocking her head. “Can you hear them?”

Delphine sniffed as she retrieved the brush from Lili’s dressing table. “Who cares? Silly old men.” While her back was turned, Lili hopped off the bed and tiptoed out into the upstairs hallway of Hôtel Bercy. The dog jumped down to follow her.

“Stanislas-Adélaïde! Come back here!” she heard Delphine scold. “You’re practically naked!” Lili turned and put her finger to her lips. “I’m going to try to listen.”

“Well, at least put on your robe! I can see the outline of your bottom under your chemise!” Ignored, Delphine gave a dramatic sigh and, throwing on her dressing gown, came out into the hallway. “It’s freezing,” she whispered, picking up the tiny bichon frise and holding it to her chest. “Look! Tintin is shivering, even with his fur coat.” She nuzzled him. “Aren’t you, mon petit?”

“Shh!” Lili held a finger to her lips. “They’re talking about the Jansenists, I think. Or maybe it’s the Jesuits. It’s hard to hear.” Lili stood by the railing at the top of the staircase and cocked one ear. “I thought I heard someone call Jesuits a plague on France, but that can’t be right.” She listened again. “Or maybe it was that there’s no place for them in France, but that doesn’t make much sense either.” She looked at Delphine. “They’re priests. How could anyone think there’s no need for priests?”

“You’ll need one soon enough if you catch your death of cold,” Delphine said, prancing on her bare toes. “My feet are turning to ice.”

The voices downstairs had quieted again to an indistinguishable murmur. Lili suddenly became aware of floorboards so cold they burned her toes and sent goose bumps up her arms and legs. “Race you to bed!” she said with a grin as she dashed past Delphine. The two girls leapt onto the soft pile of bedcovers, and Tintin joined in the jumble of arms and legs, licking their eyes and noses until they squealed.

“Time for your hair,” Delphine reminded her. Lili sat up, with Tintin in her lap, and Delphine knelt behind her. Lili closed her brown eyes in contentment as Delphine brushed her hair, but Lili’s ears remained focused on the murmuring downstairs. “I’d like to know what they’re so passionate about, wouldn’t you?”

“Who?”

“The men at Maman’s salon.”

“Unless it’s about me, I don’t really care,” Delphine said. She sat back on her haunches. “It would be rather nice to be Maman, wouldn’t it? So beautiful and kind that everyone comes to her salon because they’re secretly in love with her.”

She crawled around in front of Lili, shooed the dog away, and laid her head in Lili’s lap. “My arm’s tired. Tell me a story,” she pleaded. “About a beautiful princess. I don’t care which one.”

“Don’t you get tired of those? How about ‘Puss and Boots,’ or something else for a change?”

Delphine glared at her and said nothing.

“All right,” Lili conceded. “If you promise that just one will put you to sleep.”

“Promise.”

Lili took a deep breath. “Once upon a time …”

Corinne, the girls’ femme de chambre, gave a cursory knock on the door frame before coming in. “I beg your pardon, mam’selles,” the young servant said with a quick curtsey. “Madame said I am to make sure you have a good sleep before you return to the abbey tomorrow.” She went to the table and extinguished an oil lamp. “Madame says that you may sleep in one bed if you wish.”

With a groan of annoyance, Lili wiggled out from under Delphine’s head and lay down beside her. When Corinne had arranged the covers over them, she blew out the candles, and shut the door behind her. Lili immediately sat back up in the dark, and Delphine resumed her position on her lap.

“Once upon a time there was a king and queen who had no children for years and years. Finally they had a baby daughter, and they asked seven fairies to be the godmothers. But they forgot about one fairy, who was so old she rarely left her tower.”

“An ugly fairy,” Delphine murmured. “With one good eye.”

“Mmm. When she arrived and saw there was no place for her at the christening banquet, she was angry, and she cursed the baby girl to die of a spindle prick before she could be married …” Lili stroked Delphine’s forehead. “Sleepy yet?”

“Of course not. You barely started. But skip to the part about the dresses she wore.”

“Let’s say the princess was called …” Lili pretended to be choosing a name before coming up with the same answer she always did. “Princess Delphine.” Delphine sighed her approval and wiggled deeper into Lili’s lap. “A new dress magically appeared for her every morning, and her petticoats left a trail of sparkles behind her.”

“Sparkles?”

“Well, they are magic dresses,” Lili said. “Do you like it?”

“Oh yes,” Delphine whispered. “Put the sparkles in every time.”

“One day the beautiful princess was wandering through the palace and she saw an old woman spinning …”

By the time Lili reached the point where Sleeping Beauty was awakened from a hundred-year sleep, Delphine’s breathing was shallow, and her head was heavy on Lili’s lap. “The prince noticed right away that her gown was hopelessly out of style,” Lili continued. “Even his grandmother would not have been seen in public wearing it.” If Delphine were awake, they would have added detail after ugly detail to the dress, but her breathing did not change. “So the wolf went to the grandmother’s house and tricked the little girl into getting into bed with him. Then he ate her up, and they all lived happily ever after.” Lili waited a few seconds before transferring Delphine’s head to a pillow and snuggling in next to her.

She heard the voices of two departing guests and the sound of horses’ hooves in the street just beyond the courtyard of Hôtel Bercy. What could they care enough to argue about week after week? Certainly not fairy stories, or anything she and Delphine were taught at the convent. Tintin snored softly next to her, and Delphine murmured something in her sleep. Lili yawned and put her arm around her, and let her thoughts drift off into nothing.

* * *

A SPRING THUNDERSTORM had drenched the city overnight. The next morning Corinne held up the backs of Lili’s and Delphine’s skirts to avoid muddying their hems in the few steps to the carriage, and sent them off before Maman was awake. The sky was clearing, but one gray cloud after another drifted in front of the sun, darkening the coach bearing the two girls down the Rue Saint-Antoine toward the center of Paris.

Wrapped in the gloom that always overcame them on these mornings, neither girl said a word as the carriage made its way between the narrow rows of shops and houses lining the Pont Notre-Dame, and then rattled across the Île de la Cité and the Petit Pont to the far side of the Seine. Though their private room at the Abbaye de Panthémont was furnished at Maman’s expense with soft bedcovers and a thick rug on the floor, life at home was as cozy as the thick warm chocolat and fresh-baked brioche they had eaten for breakfast that morning. Being at Hôtel Bercy meant not having to get up for prayers and going to sleep only when Maman remembered to send Corinne. It meant being asked what they would like for supper, and having a dog that would beg and roll over for the tiniest scrap smuggled from the dining room.

Delphine sniffled. “I hate Sister Thérèse.” After a moment she added, “But not as much as I hate Sister Jeanne-Bertrand.” Lili was silent, and Delphine went on. “I can’t do anything well enough for them.” She pinched her nostrils. “‘Ladies don’t get ink on their fingers when they write,’” she said in an imitation of Sister Jeanne-Bertrand so perfect that Lili giggled in spite of her dark mood.

In Rue Saint André-des-Arts, the coach slowed to a stop. Obstructions in the streets were common enough that Delphine took no note. “‘A lady’s quality can be seen in the way she signs her name,’” she continued in the same nasal tone. “‘Your handwriting is getting bigger. It must be all the same size, or you must start again.’”

Hearing the voices of a group of children in the narrow, unpaved street, Lili pulled back the curtain and peered out. Her eyes locked on a young man in a threadbare coat, but sporting a new hat in the latest style. He was swinging his walking stick at a group of ragged children, while one of them dangled just out of reach a book-size parcel tied with string.

“Give it back!” he shouted, as another boy with a dirty face and unkempt hair made a grab for the man’s coat pocket. Two women in shabby dresses and soiled white caps watched the commotion from the doorway of a bakery, with no more interest than if they were watching birds peck for crumbs. Another passerby, older and slightly better dressed, grabbed one of the children and shoved him to the ground.

“Street scum!” he hissed, kicking the boy over and over again. “Get out of here before I knock your rotten little teeth out!” Neither woman made any move to intervene, but one of them shook a fist. “Leave him alone!” she said. “Can’t you see he’s got nothing in this world, and you so rich and all?”

The boy holding the parcel grinned and cocked his head as he danced backward down the street, and the others who had escaped the man’s wrath followed slowly enough to convey they were not frightened in the least by anyone or anything. Lili’s carriage started forward with a lurch, just as another coach passed in the other direction and sprayed thick, black mud onto the window where her face was pressed. Startled, Lili sat back, but she immediately leaned forward again to look out through the one spot that was not covered with slime. Splattered black from head to toe, including the new hat, the two men waved their fists in the air, cursing the world.

Lili giggled for a moment, before pressing her gloved fingers to her mouth so Delphine wouldn’t notice. She was sure to turn the men’s misfortune into something to joke about, and what happened really wasn’t funny. The carriage had barely moved before stopping again, and Lili craned her neck to keep watching. The boy had gotten up and was now walking in their direction, showing no signs at all that he had just been kicked repeatedly in the ribs. He had his hands in his pockets and under his muddy cap he was grinning and bobbing his head as if he might be humming a tune.

He stopped for a moment to make sure the older man wasn’t watching and then pulled a gold watch from his pocket. As he brushed a spot of mud from its surface, he looked up and saw Lili watching him from the carriage. With a smirk, he swung it by the fob for a moment just to make sure she saw. Then he stuck out his tongue and ran down an alley before the man had a chance to notice his pocket had been picked.

ALONG THE RUE de Grenelle, the tight squeeze of buildings and narrow streets gave way to more stately buildings and patches of tidy gardens as the street left the city and became a country road connecting the farming village of Grenelle with Paris. Just before the grounds of Les Invalides, the coach pulled up at the Abbaye de Panthémont. A porter and a young novice emerged from the imposing stone building, and the girls and their belongings were whisked inside.

Despite the chill lingering in the walls, the fire was unlit, as it was May. Lili unwrapped the copy of Madame d’Aulnoy’s fairy tales she had brought from home. She opened it to the place she had left off, marked by a ribbon between the pages. “I wish I could stay here and read,” she said, looking at the engraving of the sad and ragged princess Finette Cendron.

Delphine sighed as she unlaced her boots. Shivering in the musty cold, they changed out of their traveling clothes and into the simple dresses that were the uniform of the convent, before going out into the hallway.

“Time to say hello to Mother-Ugly,” Delphine whispered softly enough not to be overheard. At one point in her life, Abbess MarieCatherine had lost an eye, and though the embroidered black velvet patch she wore was tasteful, a one-eyed nun was enough to warrant horror, if not abject fear.

“Do you think she used to be a pirate?” Delphine had asked when they were eight and saw her for the first time.

“I’m quite sure not,” Lili had said. “Maybe she was born that way. Maybe she had a tiny eye patch even then. A pretty white one to match her christening bonnet.”

Delphine’s eyes were huge. “Do you really think so?”

“Maybe a raven pecked her eye out,” Lili went on. “You know, like the birds who ate Prometheus’s liver.”

“Over and over again,” Delphine shuddered. She thought for a moment. “Do you think perhaps she was supposed to be born a Cyclops and some goddess had mercy on her and softened the curse?”

“Or maybe an evil wanderer in the streets of the Faubourg Saint-Germain scooped it out with a spoon.”

Lili knew she had gone too far when she saw Delphine’s face. “Things like that can’t happen to us, can they?” Delphine had whimpered.

Lili rushed to reassure her that she just liked to make things up, and Delphine forced her to promise never to invent anything that involved people who might actually live in Paris.

A few minutes later, the two made the short visit required of returning girls, and before being turned away by a servant, they caught a glimpse of the abbess without her patch. Over the hollow cavity, her lids had been sewn together, and the scars formed what looked like stubby white eyelashes. The girls backed away in shock and ran to their room, where Delphine vomited into a washbasin and Lili retched in sympathetic dry heaves until her stomach was sore.

Still, Lili told Delphine later, when she had a chance to think about it some more, it wasn’t fair to blame the abbess, because it was hard to imagine how losing an eye was her fault.

“I know,” Delphine said, “but still, there should be something she can do not to bother people so much.”

“Perhaps she could wear a hood that covered her whole face, with one hole for her good eye,” Lili suggested. She meant it as a joke, but Delphine took all solutions seriously, including wearing shimmering veils like a harem girl, until Lili pointed out how unlikely that would be for a nun.

Finally Delphine dismissed the entire subject. “All I know is I would never let that happen to me,” she said, touching each of her eyes tenderly. “I’d die first, wouldn’t you?”

Wondering for a moment if losing an eye might give someone a secret, compensatory magic, Lili didn’t respond. Maybe that’s the real reason the abbess is so frightening, she thought. She has a power we don’t even know about. “I think I’d have to wait and see,” she finally replied. “It’s probably a good idea to wait to see how desperate you really are.”

THE AFTERNOON OF their return to the abbey, Lili and Delphine went with a few other girls to a wood-paneled study with large windows giving out onto a lawn bordered with tidy flowers and neatly clipped hedges. Sister Thérèse, their catechism nun, was leafing through one of the leather-bound books in an ornately carved bookcase.

“Good afternoon, madame,” each girl said before taking her place on one of the couches arranged around a fireplace.

“Bien,” the middle-aged nun said, coming over to her chair without sitting down. “Shall we pray?” The girls all stood up and crossed themselves, and Lili heard Delphine suppress a burp from their just-completed midday meal. “in nomine Patris, et Filii, et Spiritus Sancti, Amen,” they murmured before droning an Ave Maria and a Pater Noster. Sister Thérèse gestured to them to sit down, and after she was settled in an armchair facing them, she opened her book.

“Today is the feast day of Saint Solange,” she said, looking over the top of her spectacles at the girls. “Would anyone like to tell us who this blessed martyr was?”

Delphine straightened her back so quickly that Lili thought she might fly off the chair. “She was a shepherdess on the estate of the Comte of Poitiers, who had an evil son,” Delphine blurted out, and though her feet were hidden under her skirt, she jiggled them so intensely that Lili felt the motion against her own thigh.

“Young ladies, wait to be called upon,” the nun said. “And don’t speak so quickly. It isn’t becoming to sound so excited.”

“Oui, Sister Thérèse,” Delphine said, looking down at her lap. “Saint Solange took a vow of chastity because she was so devoted to God and when the count’s horrid son Bernard tried to—tried to—”

“Tried to force himself on her,” the nun prompted.

“Oui, Sister Thérèse. When he tried to do that, she resisted him with all her might, so he killed her.”

Sister Thérèse frowned. “Does someone else feel they can tell the story with the dignity it warrants?”

Lili felt Delphine sit back in surprise, and knew that back in their room she would be in tears. “What did I do wrong?” she would ask. “Didn’t I know the story? Didn’t I care enough about that stupid saint?”

“Mademoiselle de Praslin,” the nun said, “would you be so kind as to say what happened, and do so with the proper demeanor for a lady?”

Delphine pushed her hand down in the space between her skirt and Lili’s. Lili’s hand followed, and squeezing their interlaced fingers, they stared at the floor while Anne-Mathilde de Praslin spoke. Anne-Mathilde was the daughter of the Duc de Praslin, one of the richest and most powerful men in France. At twelve, she was two years older than Lili and Delphine, and her body was beginning to take on the curves of a woman. Her hair was pale gold and her skin, a radiant ivory, was so lacking in flaws it seemed to be made of something other than flesh. “A perfect beauty,” Lili had overheard one of the nuns remarking. “A bride worthy of a great noble of France.” If Delphine hated Sister Thérèse, she truly loathed Anne-Mathilde—a sentiment she could count on Lili to embellish in the darkness of their room.

“Bernard tried a number of times to grab Solange and force her to the ground,” Anne-Mathilde said in a deliberately musical voice, casting a gloating look at Delphine that only Lili saw. “But Solange prayed to the Blessed Virgin, who gave her the strength to fight him off. He was angry, not just because he couldn’t have her, but because she had embarrassed him in front of his friends.”

Anne-Mathilde’s best friend, Joséphine de Maurepas, nodded. “If I may add a detail,” she said in a voice so simpering, it was all Lili could do not to grab the girl’s hair and twist it until she squealed. Joséphine was also twelve, like Anne-Mathilde, but so scrawny it was hard to imagine she would ever look like anything but a little girl. The drab ash-brown of Josephine’s hair and the way she scurried around in thrall of her best friend made Lili think of the little mice she’d watched the scullery maids shoo away with a broom at home.

“I’d like to remind everyone that Bernard fell off his horse once trying to reach down and pull Solange onto it,” Joséphine was saying. “To fall off a horse for a peasant girl …?” Her voice curled up, as if she were asking whether anyone in the room really needed her to explain the disgrace.

Sister Thérèse gave them each a nod of approval. “And now, Stanislas-Adélaïde,” she said, her eyes narrowing, “will you finish the story for us?”

I should have known Sister Thérèse would do this, Lili thought. Delphine had been ridiculed, and now Lili had to retell the part of the story Delphine relished most. Lili withdrew her hand and brushed her ear, the secret signal with which she and Delphine warned each other to keep a straight face regardless of what was said next.

“I can certainly do that, Sister Thérèse,” Lili said, copying Anne-Mathilde and Joséphine’s unctuous tone. “Because at home Mademoiselle de Bercy and I often discuss the important message about piety the story contains for girls our age.” A lie is a small sin, she thought, especially for Delphine. “However, I find it particularly edifying to hear Delphine tell it, and I believe the others have not had that opportunity. May I ask if she might be permitted to finish the story herself?”

Lili heard the rustling of Anne-Mathilde’s and Joséphine’s dresses and knew without looking that their faces were shining with anticipation of something new to disparage. Sister Thérèse stared at Lili for a moment before she spoke. “If Mademoiselle feels she can control her urge to tell it so breathlessly?” Her eyebrows arched as she turned to Delphine.

“Bernard beheaded her,” Delphine said. “But even with her head on the ground, she was able to invoke the name of God three times.” Though Delphine may have sounded demure and ladylike, Lili recognized the discouragement in her tone. At home, away from the nuns’ disapproval, Delphine would have stood up and tapped her shoulders and neck with her hands, as if surprised to realize that her head was no longer there. “Mon Dieu,” she would have said in a loud voice, before repeating it more plaintively as she crumpled to the floor. “Mon Dieu,” she would have whispered a third time, tapping the floor like a blind person until she found her head and picked it up.

“Then Solange walked into the town,” Lili heard Delphine say. “It wasn’t until she reached the church that she fell to the ground and died.”

“May God’s holy name be praised,” Sister Thérèse murmured, and everyone made the sign of the cross.

“Did I do better?” Delphine asked, her voice rising in hope of at least faint praise.

“It was an improvement,” the nun said. “But it isn’t seemly for a young lady to beg for approval.” Anne-Mathilde and Joséphine stifled a giggle behind their hands.

“I understand,” Delphine said. Lili could hear the tremor in Delphine’s voice. “I want nothing more than to improve myself,” Delphine added. Lili looked to see if she was touching her ear, but she wasn’t.

“And with God’s grace, you will succeed, my child,” Sister Thérèse said. “With God’s grace, and with faith, anything is possible.” She crossed herself. “After all, look at our blessed Saint Solange.”

“Oui, Sister Thérèse.” Out of the corner of her eye, Lili saw Delphine cross herself. She rushed to do the same, but so quickly that she did it again, just to make sure it counted.

DELPHINE’S TEARS GAVE way to exhausted sniffles and then to light snoring in their room that night. The candle was still lit, and Lili picked up her book of fairy tales to read until her mind was quiet enough for sleep.

“Once upon a time there was a king and queen who ruled so badly they lost their kingdom, and they and their three daughters were reduced to day labor.” The story of Finette Cendron was one of Lili’s favorites, but tonight none of the stories in the book was likely to amuse her.

She went to the desk and took out a sheet of paper already nearly full of penmanship exercises. I could try writing a story myself, she thought. She touched the tip of a quill in the inkwell on the desk. Then, squinting to focus in the dim light, she began.

“Once upon a time …”

Once upon a time what? She thought for a moment, and suddenly it came to her.

“Once upon a time, there was a girl living in a dreary village who wanted nothing more than to travel to the stars. Her name was …”

Lili thought for a moment. She could call her Delphine and put some dresses in the story, but she didn’t want to do that. She scratched out the last three words and dipped her quill again.

“Meadowlark had a laugh like a songbird, so everybody called her Meadowlark. Every night Meadowlark would sneak outside and hope with all her might that her wish could come true. And then, to her surprise, one night a horse made of starlight appeared in front of her. ‘Are you the girl named Meadowlark?’ the horse asked. When she said yes, the horse snorted and reared up. ‘My name is Comète,’ it said. ‘Climb on my back.’ Before she knew it, Comète had galloped off with her into the night sky, leaving behind a trail of stars wherever its hooves touched.”

Lili’s eyes ached in the flickering candlelight. She would have to stop. Dipping her pen one more time, she wrote in big letters at the top of the page, “Meadowlark, by S.-A. du Châtelet.”

© 2011 Laurel corona

Recenzii

"Finding Emilie gives us an irrepressible heroine in the young Lili du Châtelet, whose life is full of engrossing surprises, mysterious journeys into old, crumbling French estates... and the rumbling terrors of the French Revolution soon to come.”

—Stephanie Cowell, critically acclaimed author of Claude & Camille

“A remarkable novel.”

—Catherine Delors, author of For the King

“This book captures the spirit of the brilliant but controversial and often scandalous Emilie in her daughter Lili’s own search for truth and happiness.”

—Anne Easter Smith, award-winning author of The King’s Grace

—Stephanie Cowell, critically acclaimed author of Claude & Camille

“A remarkable novel.”

—Catherine Delors, author of For the King

“This book captures the spirit of the brilliant but controversial and often scandalous Emilie in her daughter Lili’s own search for truth and happiness.”

—Anne Easter Smith, award-winning author of The King’s Grace

Descriere

This book captures the spirit of the brilliant but controversial and often scandalous Emilie in her daughter Lili's own search for truth and happiness.--Anne Easter Smith, award-winning author of "The King's Grace."

Notă biografică

Laurel Corona is the author of Finding Emilie, Penelope's Daughter, The Four Seasons, and Until Our Last Breath: A Holocaust Story of Love and Partisan Resistance.

Premii

- San Diego Book Awards Winner, 2012