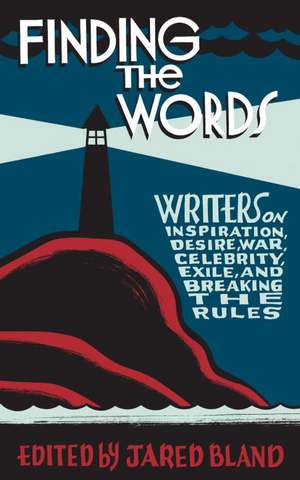

Finding the Words: Writers on Inspiration, Desire, War, Celebrity, Exile, and Breaking the Rules

Editat de Jared Blanden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2011

In Finding the Words, thirty-one well-known writers share deeply personal discoveries and stories that will surprise, delight, and stir the mind and heart. By turns inspiring, provocative, witty, and compelling, these diverse and original pieces explore home, exile, and the search for a place to belong; community, creativity, celebrity, and the many forms power can take.

Among the pieces in the anthology: Diana Athill and Alice Munro discuss the consequences of writing about other people; Gord Downie meditates on what it means to be a songwriter by considering one of his own songwriting heroes; Guy Gavriel Kay reflects on how his relationship with his own readers continues to change; Elizabeth Hay searches for inspiration in the fallow period between books; Rawi Hage meditates on writing rooted in the universal experience of exile; Pasha Malla and Moez Surani present a funny and confounding list of “rules for writers” solicited from non-writers; Heather O’Neill tells the story of an illiterate and underage wannabe gangster in mid-century Montreal; Michael Winter pieces together court transcripts, newspaper accounts, and other primary sources to take us into the dark heart of a real-life Newfoundland crime story.

Proceeds from this volume will go to PEN Canada in support of its vital work in defence of freedom of expression and on behalf of writers around the world who have been silenced.

Finding the Words Contributors List:

Diana Athill

Tash Aw

David Bezmozgis

Joseph Boyden

David Chariandy

Denise Chong

Karen Connelly

Alain de Botton

Emma Donoghue

Gord Downie

Marina Endicott

Stacey May Fowles

Rawi Hage

Elizabeth Hay

Steven Heighton

Lee Henderson

Guy Gavriel Kay

Mark Kingwell

Martha Kuwee Kumsa

Annabel Lyon

Linden MacIntyre

Pasha Malla

Lisa Moore

Alice Munro

Stephanie Nolen

Heather O’Neill

Richard Poplak

Moez Surani

Miguel Syjuco

Madeleine Thien

Michael Winter

With cover design and illustration by Seth

www.pencanada.ca

Preț: 153.01 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 230

Preț estimativ în valută:

29.28€ • 30.57$ • 24.23£

29.28€ • 30.57$ • 24.23£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780771013690

ISBN-10: 0771013698

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 137 x 221 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

ISBN-10: 0771013698

Pagini: 320

Dimensiuni: 137 x 221 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Editura: McClelland & Stewart

Notă biografică

JARED BLAND is the managing editor of The Walrus and sits on the board of directors of PEN Canada. His writing has appeared in The Walrus, the Globe and Mail, and Toronto Life. He lives in Toronto.

Extras

HEATHER O’NEILL

A Story Without Words

1

My dad was the youngest of nine children. My grandmother’s first husband, with whom she had four children, never returned from the First World War. They buried a little Canadian flag and his favourite hat in the backyard. Later, there were rumours that he had indeed come back and had changed his name and was living a few streets away from his family. The way my father tells it, he would be spotted on Saint Catherine Street dressed in a fur coat, swinging a cane around his finger, with his head thrown back, laughing.

My grandmother’s second husband – my grandfather – had a big laugh. He would stand on a table and sing. His name was Oscar, but he liked to be called Louis Louis. He gambled all his money away, but my grandmother said that they were never, ever hungry when he was around. He died when my father was only three years old. My grandmother was left to raise the nine children on her own in 1930, the beginning of the Great Depression. Fathers were a bit of a mystery to my dad. They were legendary creatures that you stopped believing in after a certain age, like Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy.

One of my father’s brothers was run over by a horse-drawn beer carriage. The beer company offered to pay the costs of the funeral if the family didn’t press charges. My father and his brothers walked down the street in new little black suits. The whole neighbourhood came out to admire the little boys in their tailored suits.

It was an age in which children died all the time. There was a booming business in little white coffins back then. People were always at funerals. They had to rush home from work and school to go to funerals. My father’s mother was always dressed in black because she was always in mourning. Her cheeks were always as pink as roses from standing out in the cold at the graveyard every weekend. That was why she appeared so lovely to men. And her eyes were enormous from crying. Life was much, much more unfair back then. They cried all the time back then. They had proper things to cry about.

My grandmother made my father light candles in the church for all the little babies who had gone to heaven. He imagined heaven was filled with babies with ribbons in their little curls, clutching dolls in their round fists. The babies stood up shaking the bars of their cribs, crying in heaven. The babies wanted angels to pick them up and rock them the way their mothers had. But angels were very busy. Angels had to listen to all the petitions and prayers from insensitive people who would call on them to win a baseball game.

The priests would always ask my grandmother how she was coping, but she would hurry away. The only people she told her children not to talk to were priests. Eventually, they took two of my dad’s older brothers away and put them in orphanages when my grandmother wasn’t looking. The priests were always taking children away. They would get money from the government for every child they collected. The way my dad tells it, there were priests in their long black coats, hiding behind garbage cans with big butterfly nets waiting to swoop up unsuspecting babies. There was no point in trying to get your children back once they believed in God. They looked down on you and thought that you were mad. They insisted that you put your nickels in the collection plate.

In terror of the priests and death, my grandmother returned for a time to Prince Edward Island, where she was from. She had moved to Montreal looking for dashing men and wondrous fortune and she returned with nothing but hungry boys.

My dad doesn’t have many memories of Prince Edward Island. He says that a goose fell madly in love with him. It followed him everywhere he went. The goose was incredibly demanding. He could never love the goose the way it needed to be loved. Who can really love anybody the way that person needs to be loved? It’s hard enough now; it was impossible during the Depression. He and his mother spent the days going to big houses trying to get work, or charity. One old lady they were visiting handed my dad a plate of lemon cookies. He devoured them greedily. Afterwards, as they were walking home, his mother asked why he couldn’t have at least saved one cookie for her. He says he never felt so bad in all his life.

His mother decided to return to Montreal. The goose wept and wept when it heard the news. What could my father say? He never knew what happened to the goose. That’s the way things were back then. You lost one another so easily.

Back in Montreal, his mother found a job as a janitor. She worked every day washing the floors of Baron Byng high school on St. Urbain Street. One winter someone stole her coat. She couldn’t afford a new one, so she had to run to work every day. She never had anything new. She didn’t have any magic tricks for any of her boys. She couldn’t pull coins out of anyone’s ears. She had to yell all the time just to be able to get all the scolding done. She had to start yelling before she even opened her eyes in the morning. Who knows if she imagined anything? If she had time to sit around thinking about Prince Charming and frogs that begged to be kissed? The boys just stayed out of her way and hung out on the street corners and in the alleys of Montreal like cats sent out to roam.

2

Then my father started school with the other neighbourhood boys his age. On the first day of kindergarten, the teacher called out Patrice and Charles and Raymond. No one answered. They all thought that their names were Buddy and Itchy and Blackie and Pepe LePuke. His mother never packed him a lunch. Once his teacher gave him a sandwich to eat in the coat closet, so that the other children couldn’t see and he wouldn’t be embarrassed. Another time she asked him why he didn’t tie his shoelaces. He told her that no one had taught him. No one taught him anything.

Over the next four years at school, my dad wasn’t able to learn to read. The grade three teacher called his mother in and told her that he had trouble reading. His mother was humiliated. Single mothers are always easily humiliated. They identify too much with their children. They are too proud of their accomplishments and too ashamed of their failures. They are terrible for their children. She was mortified and didn’t want to be called into the school ever again. She decided that he shouldn’t go back to school at all. That was her way of solving the problem. So my dad left school in grade three. After that, he was always looking for a way to make enough money to get something to eat. He sometimes sold roses that he’d dug out of the graveyard garbage bin on the street corner. He tried selling newspapers but he would get beat up mercilessly by the older boys who worked the busy street corners. Finally he was left sitting on his pile of newspapers by the river with only the mice hopping by. Mice are not big newspaper readers.

He used to go with his cousin Marie to sing in a rich woman’s house. The woman would invite her friends over to watch the sweet poor children sing. They would sing little French songs. He would get dizzy from singing while hungry. She would always give them fancy treats to eat that they were crazy about. Candied apples and bags filled with cookies. They would eat them on the street corner feeling horribly guilty because they knew that they should be saving some for their mothers. One day the woman gave my dad a whole quarter as a reward for fainting at the end of his rendition of “Le Petit Navire.” When he saw the quarter in his palm, my dad could think of only one thing: he was going to go see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

He needed more than money to get into the movie, though. There had been a great fire in a movie theatre in Montreal several years before. Loads of little children were trampled to death or died of smoke inhalation. The mayor or the prime minister or the judges or the politicians decided that children couldn’t go to the theatre by themselves anymore. They had to be accompanied by an adult.

He stood outside the movie theatre, approaching adults going in. He asked if they would pretend that he was their child. Finally a man agreed to be his father, if just for a second, at St. Peter’s Gate. It was the first movie my dad had ever seen. My dad says it was so beautiful that he almost wept. It was like being in a garden of flowers that whispered, “I love you.” Butterflies were everywhere. He never wanted the movie to end. He didn’t want to grow up and be burned out by the world like his mother. He wanted to feel and feel and feel. He always wanted to feel the way he did while watching Snow White.

3

One day my dad looked over a fence in an alleyway and saw a pretty little girl sitting in a backyard. She had a big basket of potatoes and a pot of water at her feet. She was pretending that the potatoes were her babies. She would pick up a potato and kiss it and beg it to stop crying. She would tell the potato that it was time to undress and get into bed. Then she would peel the potato and put it gently in the pot of water.

My dad climbed over the fence and introduced himself.

The girl said her name was Sally and asked if he wanted to play Bluebeard. They would pretend to get married and then he would chase her around the yard threatening to kill her. My dad had never heard of Bluebeard. He was worried that the little girl might be completely mad. His eldest brother had warned him about girls who are off their rockers. They lured you into their houses with sweet words and then locked you in and never let you leave. They forced you to have loads and loads of babies and then put a spell on you that made all the hair fall off your head.

Sally explained that Bluebeard was just a story in a book. She went into her house and came out with an enormous book filled with fairy tales. They sat next to each other on her back step as she read him the story of Bluebeard. He felt so happy and little and protected listening to the story. No one had ever read to him before. He wished that he could read. All the stories that you would know! How boring this world was! He begged Sally to read him another one.

Sally turned the page and read him the story of Puss in Boots. It’s the story of a very clever cat who gets the job done. The cat is an accountant, a foreign diplomat, and an investor. He is wicked when he needs to be wicked.

After reading half the stories in the book, Sally lost her voice. She asked my dad to read her one. But he couldn’t because he still didn’t know how to read. He had left school seven years earlier and hadn’t been able to figure out a single word since. My dad stood by and watched all his other friends read words: comic books, movie marquees, labels of clothes, newspaper headlines, street schedules, bus directions, the fortunes in fortune cookies, Valentine’s Day cards. You realize how much there is to read when you cannot read a thing. So many things are just beyond your grasp, like looking at a pile of sweets behind a window, like not being able to run in a dream. Everything is like a lottery ticket and you can’t scratch the gold off.

4

My dad’s family moved every year. Their apartments were always cold and falling apart and they always expected the next one to be a little bit better. But during the first night in a new house, they could still hear bugs crawling around under the wallpaper and they knew it was no different.

One year they moved a little farther away, to a place in Chinatown. My dad met a group of gangsters that were hanging out there at the time. The gangsters called the kids over and introduced themselves. Whenever he described them to me when I was a kid, I would imagine the fox in the top hat and the cat in the waistcoat who stopped Pinocchio on his way to school, to entice him into a life onstage. It is easier to romanticize criminals from back then. They wore suits and fedoras on the sides of their heads. They had the reputations of rock stars. They had names like Lucien La Boeuf and One-Eyed Maurice. It seemed that being a criminal was a legitimate profession.

For some people, there was no choice but to steal. It was nothing to be a bank robber. In elementary school, when the teacher asked what the children wanted to be when they grew up, at least three or four would say bank robber. There were so many bank robbers. They would come out at night with the alley cats. They would be riding the all-night bus. The diners would be filled with men with black masks on. There would be loads of them up on the rooftops, sitting there worried about the competition. One of the gangsters my dad met was Johnny Young.

Johnny Young was a magician like Harry Houdini. Except that whereas Houdini liked the limelight, Johnny Young flourished in the shadows. He was the reason you put more and more locks on your doors. People covered their houses in locks, as if their homes were impenetrable vaults. Whereas Houdini made a show of getting out of such contraptions, Johnny Young made a spectacle of getting into them.

Johnny Young was always coming off some magnificent heist. He unrolled Persian carpets and bluebirds flew out of them into the air and horses galloped off the designs and down the street. He had paintings of the Virgin Mary that actually wept. He had teacups made of porcelain so fine that they closed up at night, the way sleeping flowers do. Johnny Young was like Marco Polo returning with amazing wares that no one had ever seen before, that were meant for only rich people to lay their eyes on.

Johnny Young had a French girlfriend who was a singer. She would start singing and then everyone started singing along with her. She walked like a baby bouncing on someone’s lap. Even her curls seemed to enjoy being on her head. My dad couldn’t imagine his mother having ever, ever looked like that. Johnny Young and his gang were funny and clever. Especially compared with the other adults my dad met, who were always about to drop dead from exhaustion. The gang members were like aristocrats because they didn’t have to work nine-to five jobs. My dad decided that a life of crime might be for him.

5

The summertime drives everyone in Montreal a little crazy. You take off your fur hat and you can’t help but feel light-headed. Walking without your boots, you feel like a dancer. Everybody seems naked without their coats. All the girls on the bus have such a shy sweet way about them, as if you’d been married the day before and are waking up next to them for the first time. My dad was walking around with a friend of his. My dad can’t remember his name. It was either Karl, Étienne, Réjean, Philippe, Pierre, or Normand. I’m partial to the name Normand. My dad and Normand were walking down an alley. There were cats everywhere. Some meowed in French and some meowed in English, depending on which language their family spoke at home. There were dogs too. They walked without leashes back then. They said, “Hello, Governor,” under their breath and went on their way. There were flowers growing through the fences, reaching out at you like the hands of patients in asylums. There were little girls with pieces of chalk writing terrible and libellous things on the walls about boys who didn’t love them.

My dad and Normand weren’t looking for trouble. But it was very important to always keep an eye open for opportunities for crime that might arise unexpectedly. You had to spot them, like spotting the paper doors on Advent calendars that chocolates were hidden behind.

When they passed behind a bakery, the boys knew at once that it was their lucky day. The back windows of the bakery were wide open because it was such a hot day. The bakers had placed six huge pies on the windowsill to cool off. My dad and Normand quickly stacked the pies on top of each other and ran off. They were so excited! To have your heart beat like that and not have it kill you! That was youth.

They climbed up a fire escape and onto the roof of a building. They sat down cross-legged up in the sky and began cutting slices out of the pies with a pocket knife. Eating made them happy. All their dreams for the moment had come true. There were strawberry, apple, and rhubarb pies. They were so full that they thought that they would never be hungry again. They had never imagined there was a point that you could reach where you had had enough pie and didn’t want any more.

They sat on the roof feeling satisfied. They were so high up that clouds were right around their shoulders. My dad and Normand took some of the clouds in their hands. They moulded them like clay. They made them into rabbits and elephants and then put them back in the sky. People lying on their backs in the grass in the park pointed out that there seemed to be more forms in the clouds that day.

My dad and Normand looked down below at the street. The people seemed so tiny. You could put them in a dollhouse and have them cook and clean up and kiss one another, and whatever else you wanted them to do. They decided to throw the rest of the pies over the side of the building and onto the heads of passersby. As soon as they heard the sounds of people yelling, they scrambled up and started running over the rooftops. They clambered all the way down the block. They noticed another open window. They climbed in to see what fortunes this one would lead to.

The place ended up being a suit factory. Even though they were boys, they had no trouble finding suits their own size. Men were smaller back then. Some men were as small as five year- old boys. They would take off their hats to show waitresses their completely bald heads to prove that they were of drinking age.

They went back to my dad’s house with their new suits under their arms, eager to try them on. His mother would be working for hours and hours, so she wouldn’t be in their way. They scrubbed themselves clean, greased their hair to the sides, and changed into their new duds. For the pièce de résistance, they went outside, pulled up some dandelions, and stuck them in their buttonholes. Then they set off. They wanted everyone to see them in their fantastic new outfits. This was their moment to shine. They were multimillionaires.

They walked down De la Gauchetière Street, trying to pass themselves off as rich gentlemen. Their idea of how rich gentlemen behaved was an amalgamation of illustrations they’d seen in picture books, the voices of men advertising toothpaste on the radio, and villainous caped puppets that performed in the park. They knew to act fancy free as if they didn’t have a care in the world and to put a skip in their step. They also knew to talk loudly and in British accents.

“It was a jolly good outing we had!” my dad exclaimed.

“A perfect day for plundering,” Normand agreed. “We did have ourselves some jolly laughs.”

“That’s a boy, old chap.”

“That’s a decent sort of bloke.”

“I’ll spend a fortnight in Scotland Yards.”

“If you please, sir! If you please!”

“Cheerio, I say! Cheerio!”

“Yes. Yes. Well done!”

Johnny Young spotted them right away from the window of the café he was sitting in. He knew crime had been committed, the way that leopards are able to detect a small animal moving about in the dark. When Johnny Young walked out of the café and stood directly in their paths, my dad and Normand started making up a story about a new job or a wedding. Johnny Young screwed up his eyes, as if listening to their lies were like listening to an out-of-tune piano.

Johnny got them to admit they’d stolen the suits. He also got the two boys to take him and his cronies back to the factory. My dad climbed up the fire escape and opened the doors for every one to get inside. They all got arrested.

A Story Without Words

1

My dad was the youngest of nine children. My grandmother’s first husband, with whom she had four children, never returned from the First World War. They buried a little Canadian flag and his favourite hat in the backyard. Later, there were rumours that he had indeed come back and had changed his name and was living a few streets away from his family. The way my father tells it, he would be spotted on Saint Catherine Street dressed in a fur coat, swinging a cane around his finger, with his head thrown back, laughing.

My grandmother’s second husband – my grandfather – had a big laugh. He would stand on a table and sing. His name was Oscar, but he liked to be called Louis Louis. He gambled all his money away, but my grandmother said that they were never, ever hungry when he was around. He died when my father was only three years old. My grandmother was left to raise the nine children on her own in 1930, the beginning of the Great Depression. Fathers were a bit of a mystery to my dad. They were legendary creatures that you stopped believing in after a certain age, like Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy.

One of my father’s brothers was run over by a horse-drawn beer carriage. The beer company offered to pay the costs of the funeral if the family didn’t press charges. My father and his brothers walked down the street in new little black suits. The whole neighbourhood came out to admire the little boys in their tailored suits.

It was an age in which children died all the time. There was a booming business in little white coffins back then. People were always at funerals. They had to rush home from work and school to go to funerals. My father’s mother was always dressed in black because she was always in mourning. Her cheeks were always as pink as roses from standing out in the cold at the graveyard every weekend. That was why she appeared so lovely to men. And her eyes were enormous from crying. Life was much, much more unfair back then. They cried all the time back then. They had proper things to cry about.

My grandmother made my father light candles in the church for all the little babies who had gone to heaven. He imagined heaven was filled with babies with ribbons in their little curls, clutching dolls in their round fists. The babies stood up shaking the bars of their cribs, crying in heaven. The babies wanted angels to pick them up and rock them the way their mothers had. But angels were very busy. Angels had to listen to all the petitions and prayers from insensitive people who would call on them to win a baseball game.

The priests would always ask my grandmother how she was coping, but she would hurry away. The only people she told her children not to talk to were priests. Eventually, they took two of my dad’s older brothers away and put them in orphanages when my grandmother wasn’t looking. The priests were always taking children away. They would get money from the government for every child they collected. The way my dad tells it, there were priests in their long black coats, hiding behind garbage cans with big butterfly nets waiting to swoop up unsuspecting babies. There was no point in trying to get your children back once they believed in God. They looked down on you and thought that you were mad. They insisted that you put your nickels in the collection plate.

In terror of the priests and death, my grandmother returned for a time to Prince Edward Island, where she was from. She had moved to Montreal looking for dashing men and wondrous fortune and she returned with nothing but hungry boys.

My dad doesn’t have many memories of Prince Edward Island. He says that a goose fell madly in love with him. It followed him everywhere he went. The goose was incredibly demanding. He could never love the goose the way it needed to be loved. Who can really love anybody the way that person needs to be loved? It’s hard enough now; it was impossible during the Depression. He and his mother spent the days going to big houses trying to get work, or charity. One old lady they were visiting handed my dad a plate of lemon cookies. He devoured them greedily. Afterwards, as they were walking home, his mother asked why he couldn’t have at least saved one cookie for her. He says he never felt so bad in all his life.

His mother decided to return to Montreal. The goose wept and wept when it heard the news. What could my father say? He never knew what happened to the goose. That’s the way things were back then. You lost one another so easily.

Back in Montreal, his mother found a job as a janitor. She worked every day washing the floors of Baron Byng high school on St. Urbain Street. One winter someone stole her coat. She couldn’t afford a new one, so she had to run to work every day. She never had anything new. She didn’t have any magic tricks for any of her boys. She couldn’t pull coins out of anyone’s ears. She had to yell all the time just to be able to get all the scolding done. She had to start yelling before she even opened her eyes in the morning. Who knows if she imagined anything? If she had time to sit around thinking about Prince Charming and frogs that begged to be kissed? The boys just stayed out of her way and hung out on the street corners and in the alleys of Montreal like cats sent out to roam.

2

Then my father started school with the other neighbourhood boys his age. On the first day of kindergarten, the teacher called out Patrice and Charles and Raymond. No one answered. They all thought that their names were Buddy and Itchy and Blackie and Pepe LePuke. His mother never packed him a lunch. Once his teacher gave him a sandwich to eat in the coat closet, so that the other children couldn’t see and he wouldn’t be embarrassed. Another time she asked him why he didn’t tie his shoelaces. He told her that no one had taught him. No one taught him anything.

Over the next four years at school, my dad wasn’t able to learn to read. The grade three teacher called his mother in and told her that he had trouble reading. His mother was humiliated. Single mothers are always easily humiliated. They identify too much with their children. They are too proud of their accomplishments and too ashamed of their failures. They are terrible for their children. She was mortified and didn’t want to be called into the school ever again. She decided that he shouldn’t go back to school at all. That was her way of solving the problem. So my dad left school in grade three. After that, he was always looking for a way to make enough money to get something to eat. He sometimes sold roses that he’d dug out of the graveyard garbage bin on the street corner. He tried selling newspapers but he would get beat up mercilessly by the older boys who worked the busy street corners. Finally he was left sitting on his pile of newspapers by the river with only the mice hopping by. Mice are not big newspaper readers.

He used to go with his cousin Marie to sing in a rich woman’s house. The woman would invite her friends over to watch the sweet poor children sing. They would sing little French songs. He would get dizzy from singing while hungry. She would always give them fancy treats to eat that they were crazy about. Candied apples and bags filled with cookies. They would eat them on the street corner feeling horribly guilty because they knew that they should be saving some for their mothers. One day the woman gave my dad a whole quarter as a reward for fainting at the end of his rendition of “Le Petit Navire.” When he saw the quarter in his palm, my dad could think of only one thing: he was going to go see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

He needed more than money to get into the movie, though. There had been a great fire in a movie theatre in Montreal several years before. Loads of little children were trampled to death or died of smoke inhalation. The mayor or the prime minister or the judges or the politicians decided that children couldn’t go to the theatre by themselves anymore. They had to be accompanied by an adult.

He stood outside the movie theatre, approaching adults going in. He asked if they would pretend that he was their child. Finally a man agreed to be his father, if just for a second, at St. Peter’s Gate. It was the first movie my dad had ever seen. My dad says it was so beautiful that he almost wept. It was like being in a garden of flowers that whispered, “I love you.” Butterflies were everywhere. He never wanted the movie to end. He didn’t want to grow up and be burned out by the world like his mother. He wanted to feel and feel and feel. He always wanted to feel the way he did while watching Snow White.

3

One day my dad looked over a fence in an alleyway and saw a pretty little girl sitting in a backyard. She had a big basket of potatoes and a pot of water at her feet. She was pretending that the potatoes were her babies. She would pick up a potato and kiss it and beg it to stop crying. She would tell the potato that it was time to undress and get into bed. Then she would peel the potato and put it gently in the pot of water.

My dad climbed over the fence and introduced himself.

The girl said her name was Sally and asked if he wanted to play Bluebeard. They would pretend to get married and then he would chase her around the yard threatening to kill her. My dad had never heard of Bluebeard. He was worried that the little girl might be completely mad. His eldest brother had warned him about girls who are off their rockers. They lured you into their houses with sweet words and then locked you in and never let you leave. They forced you to have loads and loads of babies and then put a spell on you that made all the hair fall off your head.

Sally explained that Bluebeard was just a story in a book. She went into her house and came out with an enormous book filled with fairy tales. They sat next to each other on her back step as she read him the story of Bluebeard. He felt so happy and little and protected listening to the story. No one had ever read to him before. He wished that he could read. All the stories that you would know! How boring this world was! He begged Sally to read him another one.

Sally turned the page and read him the story of Puss in Boots. It’s the story of a very clever cat who gets the job done. The cat is an accountant, a foreign diplomat, and an investor. He is wicked when he needs to be wicked.

After reading half the stories in the book, Sally lost her voice. She asked my dad to read her one. But he couldn’t because he still didn’t know how to read. He had left school seven years earlier and hadn’t been able to figure out a single word since. My dad stood by and watched all his other friends read words: comic books, movie marquees, labels of clothes, newspaper headlines, street schedules, bus directions, the fortunes in fortune cookies, Valentine’s Day cards. You realize how much there is to read when you cannot read a thing. So many things are just beyond your grasp, like looking at a pile of sweets behind a window, like not being able to run in a dream. Everything is like a lottery ticket and you can’t scratch the gold off.

4

My dad’s family moved every year. Their apartments were always cold and falling apart and they always expected the next one to be a little bit better. But during the first night in a new house, they could still hear bugs crawling around under the wallpaper and they knew it was no different.

One year they moved a little farther away, to a place in Chinatown. My dad met a group of gangsters that were hanging out there at the time. The gangsters called the kids over and introduced themselves. Whenever he described them to me when I was a kid, I would imagine the fox in the top hat and the cat in the waistcoat who stopped Pinocchio on his way to school, to entice him into a life onstage. It is easier to romanticize criminals from back then. They wore suits and fedoras on the sides of their heads. They had the reputations of rock stars. They had names like Lucien La Boeuf and One-Eyed Maurice. It seemed that being a criminal was a legitimate profession.

For some people, there was no choice but to steal. It was nothing to be a bank robber. In elementary school, when the teacher asked what the children wanted to be when they grew up, at least three or four would say bank robber. There were so many bank robbers. They would come out at night with the alley cats. They would be riding the all-night bus. The diners would be filled with men with black masks on. There would be loads of them up on the rooftops, sitting there worried about the competition. One of the gangsters my dad met was Johnny Young.

Johnny Young was a magician like Harry Houdini. Except that whereas Houdini liked the limelight, Johnny Young flourished in the shadows. He was the reason you put more and more locks on your doors. People covered their houses in locks, as if their homes were impenetrable vaults. Whereas Houdini made a show of getting out of such contraptions, Johnny Young made a spectacle of getting into them.

Johnny Young was always coming off some magnificent heist. He unrolled Persian carpets and bluebirds flew out of them into the air and horses galloped off the designs and down the street. He had paintings of the Virgin Mary that actually wept. He had teacups made of porcelain so fine that they closed up at night, the way sleeping flowers do. Johnny Young was like Marco Polo returning with amazing wares that no one had ever seen before, that were meant for only rich people to lay their eyes on.

Johnny Young had a French girlfriend who was a singer. She would start singing and then everyone started singing along with her. She walked like a baby bouncing on someone’s lap. Even her curls seemed to enjoy being on her head. My dad couldn’t imagine his mother having ever, ever looked like that. Johnny Young and his gang were funny and clever. Especially compared with the other adults my dad met, who were always about to drop dead from exhaustion. The gang members were like aristocrats because they didn’t have to work nine-to five jobs. My dad decided that a life of crime might be for him.

5

The summertime drives everyone in Montreal a little crazy. You take off your fur hat and you can’t help but feel light-headed. Walking without your boots, you feel like a dancer. Everybody seems naked without their coats. All the girls on the bus have such a shy sweet way about them, as if you’d been married the day before and are waking up next to them for the first time. My dad was walking around with a friend of his. My dad can’t remember his name. It was either Karl, Étienne, Réjean, Philippe, Pierre, or Normand. I’m partial to the name Normand. My dad and Normand were walking down an alley. There were cats everywhere. Some meowed in French and some meowed in English, depending on which language their family spoke at home. There were dogs too. They walked without leashes back then. They said, “Hello, Governor,” under their breath and went on their way. There were flowers growing through the fences, reaching out at you like the hands of patients in asylums. There were little girls with pieces of chalk writing terrible and libellous things on the walls about boys who didn’t love them.

My dad and Normand weren’t looking for trouble. But it was very important to always keep an eye open for opportunities for crime that might arise unexpectedly. You had to spot them, like spotting the paper doors on Advent calendars that chocolates were hidden behind.

When they passed behind a bakery, the boys knew at once that it was their lucky day. The back windows of the bakery were wide open because it was such a hot day. The bakers had placed six huge pies on the windowsill to cool off. My dad and Normand quickly stacked the pies on top of each other and ran off. They were so excited! To have your heart beat like that and not have it kill you! That was youth.

They climbed up a fire escape and onto the roof of a building. They sat down cross-legged up in the sky and began cutting slices out of the pies with a pocket knife. Eating made them happy. All their dreams for the moment had come true. There were strawberry, apple, and rhubarb pies. They were so full that they thought that they would never be hungry again. They had never imagined there was a point that you could reach where you had had enough pie and didn’t want any more.

They sat on the roof feeling satisfied. They were so high up that clouds were right around their shoulders. My dad and Normand took some of the clouds in their hands. They moulded them like clay. They made them into rabbits and elephants and then put them back in the sky. People lying on their backs in the grass in the park pointed out that there seemed to be more forms in the clouds that day.

My dad and Normand looked down below at the street. The people seemed so tiny. You could put them in a dollhouse and have them cook and clean up and kiss one another, and whatever else you wanted them to do. They decided to throw the rest of the pies over the side of the building and onto the heads of passersby. As soon as they heard the sounds of people yelling, they scrambled up and started running over the rooftops. They clambered all the way down the block. They noticed another open window. They climbed in to see what fortunes this one would lead to.

The place ended up being a suit factory. Even though they were boys, they had no trouble finding suits their own size. Men were smaller back then. Some men were as small as five year- old boys. They would take off their hats to show waitresses their completely bald heads to prove that they were of drinking age.

They went back to my dad’s house with their new suits under their arms, eager to try them on. His mother would be working for hours and hours, so she wouldn’t be in their way. They scrubbed themselves clean, greased their hair to the sides, and changed into their new duds. For the pièce de résistance, they went outside, pulled up some dandelions, and stuck them in their buttonholes. Then they set off. They wanted everyone to see them in their fantastic new outfits. This was their moment to shine. They were multimillionaires.

They walked down De la Gauchetière Street, trying to pass themselves off as rich gentlemen. Their idea of how rich gentlemen behaved was an amalgamation of illustrations they’d seen in picture books, the voices of men advertising toothpaste on the radio, and villainous caped puppets that performed in the park. They knew to act fancy free as if they didn’t have a care in the world and to put a skip in their step. They also knew to talk loudly and in British accents.

“It was a jolly good outing we had!” my dad exclaimed.

“A perfect day for plundering,” Normand agreed. “We did have ourselves some jolly laughs.”

“That’s a boy, old chap.”

“That’s a decent sort of bloke.”

“I’ll spend a fortnight in Scotland Yards.”

“If you please, sir! If you please!”

“Cheerio, I say! Cheerio!”

“Yes. Yes. Well done!”

Johnny Young spotted them right away from the window of the café he was sitting in. He knew crime had been committed, the way that leopards are able to detect a small animal moving about in the dark. When Johnny Young walked out of the café and stood directly in their paths, my dad and Normand started making up a story about a new job or a wedding. Johnny Young screwed up his eyes, as if listening to their lies were like listening to an out-of-tune piano.

Johnny got them to admit they’d stolen the suits. He also got the two boys to take him and his cronies back to the factory. My dad climbed up the fire escape and opened the doors for every one to get inside. They all got arrested.