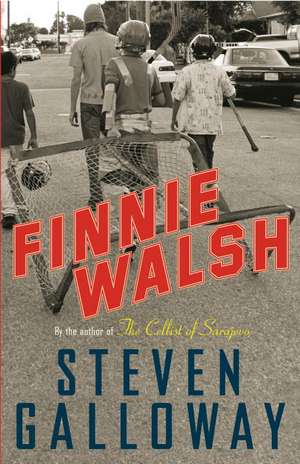

Finnie Walsh

Autor Steven Gallowayen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 ian 2010 – vârsta de la 14 ani

Finnie Walsh is a captivating, Irving-esque story of family, friendship, redemption, and legend.

Paul Woodward lives in Portsmouth, a quiet northern mill-town. Born the day Paul Henderson planted the puck between the pipes against the Soviet Union to win the 1972 Super Series, Paul has no choice about playing hockey. His best friend Finnie Walsh is stinking rich. He is also fellow hockey fanatic and the only good kid in a long line of delinquent brothers. Paul's father works the nightshift at the local mill, owned by Finnie's father. One fateful day the boys noisily prepare for their first season of hockey in the Woodward driveway, keeping Paul's father awake when he should be sleeping. This triggers a chain of world-altering events. Galloway proves that childhood innocence, while not exactly bliss, can be amusing and more than mildly instructional. This is the book John Irving would have written if he understood hockey as well as wrestling. Finnie Walsh, like the fabled games before NHL expansion, is a story about greatness and legend. But it's also a heartsong to family, friendship, and atonement.

Preț: 103.26 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 155

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.76€ • 20.51$ • 16.52£

19.76€ • 20.51$ • 16.52£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307398659

ISBN-10: 030739865X

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Knopf Canada

ISBN-10: 030739865X

Pagini: 176

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Editura: Knopf Canada

Notă biografică

STEVEN GALLOWAY is the author of three novels: Finnie Walsh, Ascension, and The Cellist of Sarajevo. His work has been translated into over twenty languages and optioned for film. He teaches creative writing at UBC and SFU, and he lives with his wife and two daughters in New Westminster, BC.

Extras

First Period

Finnie Walsh will forever remain in my daily thoughts, not only because of the shocking circumstances of his absurd demise, but because he managed to misunderstand what was truly important even though he was right about almost everything else. Finnie Walsh taught me that those in need of redemption are rarely those who become redeemed.

Finnie Walsh’s parents owned more than half of Portsmouth, the mill town of 30,000 where Finnie and I grew up. I still remember the startled look on my father’s face the first time he peered out the front window and saw me in the driveway shooting pucks with his boss’ youngest son. My father’s concern was not motivated by fear for Finnie’s safety; Finnie Walsh, a strawberry-blond, freckled boy with stubby fingers and slate-grey eyes, was not at all frail. He was of a sturdier than average build for a child his age, almost pudgy in a cheerful sort of way, and was only small when compared with his father and three older brothers, who were gigantic.

Mr. Walsh had felt that Finnie would benefit from some toughening up, so instead of sending him to the all-boys’ prep school that his brothers and most of the other children of Portsmouth’s wealthier citizens attended, Finnie was enrolled in Portsmouth Public School. It was there, in September of 1980, packed into Mrs. Sweeney’s third-grade classroom, that my friendship with Finnie Walsh began.

For four generations, the Walsh family had been Portsmouth’s main employer. My father was the most recent in a long line of men named Robert Woodward to work in the Walsh family sawmill. The older I got, the more I understood how much my father wanted me to break the cycle and work somewhere else. With this in mind, my father insisted that I not be named Robert. “Our family,” he often said, “is stuck in a rut.”

When I met Finnie Walsh, I was too young to realize that we weren’t supposed to be friends. It didn’t take long for Finnie and me, thrust together in the back row of Mrs. Sweeney’s alphabetically ordered classroom, to become inseparable. We each had substantial hockey card collections, although we were at odds about which cards were valuable and which were not.

My favourite player was Wayne Gretzky, who had just begun his second season in the NHL. Finnie’s favourite player was Peter Stastny, a Czechoslovakian rookie with the Quebec Nordiques.

“Gretzky’s okay, I guess, if you like that sort of thing. I think he’s flashy,” Finnie said.

If there was one thing Finnie Walsh didn’t like, it was “flash.” It was for this very reason that we ended up playing hockey in my driveway that day instead of the much larger and smoother driveway leading up to the Walsh estate. Finnie agreed that his driveway was in all ways superior to mine; he just didn’t want to play there.

The Walsh house was very flashy. It was situated in the middle of a seven-acre lot overlooking the river. Upstream from the mill, of course. The grounds were surrounded by an imposing wrought-iron fence. In many ways the house resembled the American White House, except that it was made of brick. Fountains, benches and a gazebo dotted a magnificently manicured lawn surrounded by an excess abundance of flowers. Mrs. Walsh had been an avid gardener. She had died when Finnie was a baby, but as a tribute to his late wife Mr. Walsh hired an extra gardener to maintain the flowerbeds.

The first time Finnie and I played hockey in my driveway, we didn’t even have a net. I drew one on our garage door with chalk and for a while we just passed the ball back and forth, taking the odd shot. My father was working the night shift that week and every time we scored the ball slammed against the garage door and woke him up.

Having had his sleep disturbed several times by a strange echoing thud, my father got out of bed and came to the front window to investigate. He peered between the drapes, watching me stickhandle, feathering a tape-to-tape pass between the legs of an imaginary defenceman. Through the window, I saw him frown and furrow his eyebrows. Finnie took the pass, went inside-out and shot one hard at the top corner. Thud! My father clenched his jaw. Suddenly it dawned on him exactly who had taken the shot. When he realized that Finnie Walsh, Roger Walsh’s son, was in our driveway, his eyebrows arched and his jaw unclenched. He disappeared behind the curtains.

Finnie and I celebrated the goal, a perfect combination of teamwork and individual skill. My mother appeared in the window. Her face changed from disbelief to shock as Finnie won the faceoff, beating the opposing team’s centre, and rifled me a pass. I took the puck on my backhand and, spinning around, gave it back to Finnie. He had gone to the net and was there to tip it by the goalie, who had no chance on the play. My mother vanished into the depths of our house.

Sometime, late in the third period, my mother opened the front door and told me that supper was ready.

“Can Finnie stay?” I asked.

She looked startled, even though I often had friends stay over for supper. “I’m sure Finnie has supper waiting at home for him already, Paul,” she said.

“Please?”

My mother hesitated, not wanting to offend Finnie. She didn’t know what to make of the situation. “Would your father mind, Finnie?” she said slowly.

“No, Mrs. Woodward. My father usually doesn’t get home until late.”

“Oh. Well, I suppose it would be all right then.”

We went inside. I caught my parents shooting each other questioning looks while my mother set an extra place for Finnie between me and my sister, Louise.

Louise squinted at Finnie; she was always squinting. Louise was two-and-a-half years older than me, a shy kid who didn’t really have many friends; she seemed content to keep to herself. She spent most of her time in the basement, where she had an impressive array of toys. Some of them most girls would never have wanted to play with. For that matter, some of them no one would have played with, boy or girl: an old ironing board, a tire jack, a collection of pine cones and duck feathers. What she did with them I never knew. I wasn’t much interested in toys then. Whenever I got a new toy for my birthday or Christmas, I would half-heartedly play with it for a few days before it was invariably relegated to the basement, a new fixture in Louise’s imaginary world.

Occasionally, when it rained or we were home sick, I would sit on the basement stairs and watch Louise rule her tiny empire. It was understood that I was not welcome to join her, not out of jealousy or spite or sibling rivalry, but because this world was hers and hers alone. She was indifferent to my presence, not ignoring me, but not paying me any special attention either. Louise’s “kingdom,” as my father jokingly called it, was an interesting but perplexing place.

“Hi, Louise,” Finnie said.

She didn’t answer him. She looked at the ground, her fingers kneading the tablecloth.

“Louise, be polite,” my mother said.

“It’s okay, Mrs. Woodward. I understand. Louise is shy.”

My father, who apparently was not used to such candour from a seven year old, nearly choked on his coffee. Louise blushed and pulled more frantically at the tablecloth.

We had meatloaf that night, which was never my favourite dish, but since then I have liked it even less. Finnie, however, looked as though he had never eaten meatloaf before and he ate it with such obvious relish that you would have thought it was lobster and caviar instead of ground beef and ketchup.

This impressed my mother immensely. She was not used to people enjoying her meatloaf. “Would you like more, Finnie?” she asked him after he had wolfed down the contents of his plate.

“I sure would, Mrs. Woodward.”

“Anyone else?”

“No thanks,” my father and I said. Louise said nothing. She wasn’t really expected to answer. My mother piled Finnie’s plate high with a block of ground beef. My father was pleased; the more meatloaf Finnie ate, the less would wind up in his lunch box. Although he never complained, my father didn’t like it when he had to eat the same meal at work as he’d eaten for supper that night.

“Did you boys have a good day at school today?” my father asked us.

“Peter Bartram threw up at recess,” I said.

“Has he caught something?” My mother always wanted to know if there was a flu going around.

“No,” Finnie said. “Jenny Carlysle kicked him in the balls.”

“Peter Bartram is an ass,” Louise said.

“Louise!” my mother said, horrified.

We were all shocked. I was shocked that Finnie had gotten away with saying “balls” at the supper table; my parents were shocked that Louise had spoken in front of a non-family member.

“She’s right, Mrs. Woodward. Peter Bartram is an ass. He beats up kids way smaller than him and he put a firecracker under a dog’s collar and lit it.”

“He did what?” my father asked.

“He put a firecracker under a dog’s collar and lit it!”

“Was the dog hurt?” My mother looked like she was going to cry.

“Not physically,” Finnie said. “But I don’t think it’s quite right anymore.”

“Why did Jenny kick him?”

“It was her brother’s dog,” I said.

“If it were my dog, I’d have done worse,” my father said.

“If it were my dog, I’d have put a firecracker in Peter’s pants,” Finnie said.

“I’d have put a nuclear bomb in Peter’s pants,” my father said.

Finnie and my father laughed. He appeared to have forgotten who Finnie’s father was. The two of them were talking like they were old friends. Even after my mother cleared away the dishes, they made no move to leave the table. Finally my father looked at the clock and stood up. “Well, I suppose it’s about that time.” That was what he said whenever he had to go to work.

“What time?” Finnie asked.

“Time to go to work,” I said.

“Now?” Finnie apparently did not know that people worked at night.

My mother handed my father his lunch box and he left.

Later, as Finnie was leaving, he thanked me for having him over. “A lot of people don’t like me because of my dad.”

“Why?” I didn’t see why that should have anything to do with it.

“I don’t know,” Finnie said. “Your dad is nice. He looks awfully tired, though.” Finnie stepped out the door and got on his bike. He smiled and rode up the street toward his house.

I closed the door and thought about what he’d said. My father definitely was nice. He often looked tired too, that was true, but that evening he’d looked especially tired.

Finnie Walsh will forever remain in my daily thoughts, not only because of the shocking circumstances of his absurd demise, but because he managed to misunderstand what was truly important even though he was right about almost everything else. Finnie Walsh taught me that those in need of redemption are rarely those who become redeemed.

Finnie Walsh’s parents owned more than half of Portsmouth, the mill town of 30,000 where Finnie and I grew up. I still remember the startled look on my father’s face the first time he peered out the front window and saw me in the driveway shooting pucks with his boss’ youngest son. My father’s concern was not motivated by fear for Finnie’s safety; Finnie Walsh, a strawberry-blond, freckled boy with stubby fingers and slate-grey eyes, was not at all frail. He was of a sturdier than average build for a child his age, almost pudgy in a cheerful sort of way, and was only small when compared with his father and three older brothers, who were gigantic.

Mr. Walsh had felt that Finnie would benefit from some toughening up, so instead of sending him to the all-boys’ prep school that his brothers and most of the other children of Portsmouth’s wealthier citizens attended, Finnie was enrolled in Portsmouth Public School. It was there, in September of 1980, packed into Mrs. Sweeney’s third-grade classroom, that my friendship with Finnie Walsh began.

For four generations, the Walsh family had been Portsmouth’s main employer. My father was the most recent in a long line of men named Robert Woodward to work in the Walsh family sawmill. The older I got, the more I understood how much my father wanted me to break the cycle and work somewhere else. With this in mind, my father insisted that I not be named Robert. “Our family,” he often said, “is stuck in a rut.”

When I met Finnie Walsh, I was too young to realize that we weren’t supposed to be friends. It didn’t take long for Finnie and me, thrust together in the back row of Mrs. Sweeney’s alphabetically ordered classroom, to become inseparable. We each had substantial hockey card collections, although we were at odds about which cards were valuable and which were not.

My favourite player was Wayne Gretzky, who had just begun his second season in the NHL. Finnie’s favourite player was Peter Stastny, a Czechoslovakian rookie with the Quebec Nordiques.

“Gretzky’s okay, I guess, if you like that sort of thing. I think he’s flashy,” Finnie said.

If there was one thing Finnie Walsh didn’t like, it was “flash.” It was for this very reason that we ended up playing hockey in my driveway that day instead of the much larger and smoother driveway leading up to the Walsh estate. Finnie agreed that his driveway was in all ways superior to mine; he just didn’t want to play there.

The Walsh house was very flashy. It was situated in the middle of a seven-acre lot overlooking the river. Upstream from the mill, of course. The grounds were surrounded by an imposing wrought-iron fence. In many ways the house resembled the American White House, except that it was made of brick. Fountains, benches and a gazebo dotted a magnificently manicured lawn surrounded by an excess abundance of flowers. Mrs. Walsh had been an avid gardener. She had died when Finnie was a baby, but as a tribute to his late wife Mr. Walsh hired an extra gardener to maintain the flowerbeds.

The first time Finnie and I played hockey in my driveway, we didn’t even have a net. I drew one on our garage door with chalk and for a while we just passed the ball back and forth, taking the odd shot. My father was working the night shift that week and every time we scored the ball slammed against the garage door and woke him up.

Having had his sleep disturbed several times by a strange echoing thud, my father got out of bed and came to the front window to investigate. He peered between the drapes, watching me stickhandle, feathering a tape-to-tape pass between the legs of an imaginary defenceman. Through the window, I saw him frown and furrow his eyebrows. Finnie took the pass, went inside-out and shot one hard at the top corner. Thud! My father clenched his jaw. Suddenly it dawned on him exactly who had taken the shot. When he realized that Finnie Walsh, Roger Walsh’s son, was in our driveway, his eyebrows arched and his jaw unclenched. He disappeared behind the curtains.

Finnie and I celebrated the goal, a perfect combination of teamwork and individual skill. My mother appeared in the window. Her face changed from disbelief to shock as Finnie won the faceoff, beating the opposing team’s centre, and rifled me a pass. I took the puck on my backhand and, spinning around, gave it back to Finnie. He had gone to the net and was there to tip it by the goalie, who had no chance on the play. My mother vanished into the depths of our house.

Sometime, late in the third period, my mother opened the front door and told me that supper was ready.

“Can Finnie stay?” I asked.

She looked startled, even though I often had friends stay over for supper. “I’m sure Finnie has supper waiting at home for him already, Paul,” she said.

“Please?”

My mother hesitated, not wanting to offend Finnie. She didn’t know what to make of the situation. “Would your father mind, Finnie?” she said slowly.

“No, Mrs. Woodward. My father usually doesn’t get home until late.”

“Oh. Well, I suppose it would be all right then.”

We went inside. I caught my parents shooting each other questioning looks while my mother set an extra place for Finnie between me and my sister, Louise.

Louise squinted at Finnie; she was always squinting. Louise was two-and-a-half years older than me, a shy kid who didn’t really have many friends; she seemed content to keep to herself. She spent most of her time in the basement, where she had an impressive array of toys. Some of them most girls would never have wanted to play with. For that matter, some of them no one would have played with, boy or girl: an old ironing board, a tire jack, a collection of pine cones and duck feathers. What she did with them I never knew. I wasn’t much interested in toys then. Whenever I got a new toy for my birthday or Christmas, I would half-heartedly play with it for a few days before it was invariably relegated to the basement, a new fixture in Louise’s imaginary world.

Occasionally, when it rained or we were home sick, I would sit on the basement stairs and watch Louise rule her tiny empire. It was understood that I was not welcome to join her, not out of jealousy or spite or sibling rivalry, but because this world was hers and hers alone. She was indifferent to my presence, not ignoring me, but not paying me any special attention either. Louise’s “kingdom,” as my father jokingly called it, was an interesting but perplexing place.

“Hi, Louise,” Finnie said.

She didn’t answer him. She looked at the ground, her fingers kneading the tablecloth.

“Louise, be polite,” my mother said.

“It’s okay, Mrs. Woodward. I understand. Louise is shy.”

My father, who apparently was not used to such candour from a seven year old, nearly choked on his coffee. Louise blushed and pulled more frantically at the tablecloth.

We had meatloaf that night, which was never my favourite dish, but since then I have liked it even less. Finnie, however, looked as though he had never eaten meatloaf before and he ate it with such obvious relish that you would have thought it was lobster and caviar instead of ground beef and ketchup.

This impressed my mother immensely. She was not used to people enjoying her meatloaf. “Would you like more, Finnie?” she asked him after he had wolfed down the contents of his plate.

“I sure would, Mrs. Woodward.”

“Anyone else?”

“No thanks,” my father and I said. Louise said nothing. She wasn’t really expected to answer. My mother piled Finnie’s plate high with a block of ground beef. My father was pleased; the more meatloaf Finnie ate, the less would wind up in his lunch box. Although he never complained, my father didn’t like it when he had to eat the same meal at work as he’d eaten for supper that night.

“Did you boys have a good day at school today?” my father asked us.

“Peter Bartram threw up at recess,” I said.

“Has he caught something?” My mother always wanted to know if there was a flu going around.

“No,” Finnie said. “Jenny Carlysle kicked him in the balls.”

“Peter Bartram is an ass,” Louise said.

“Louise!” my mother said, horrified.

We were all shocked. I was shocked that Finnie had gotten away with saying “balls” at the supper table; my parents were shocked that Louise had spoken in front of a non-family member.

“She’s right, Mrs. Woodward. Peter Bartram is an ass. He beats up kids way smaller than him and he put a firecracker under a dog’s collar and lit it.”

“He did what?” my father asked.

“He put a firecracker under a dog’s collar and lit it!”

“Was the dog hurt?” My mother looked like she was going to cry.

“Not physically,” Finnie said. “But I don’t think it’s quite right anymore.”

“Why did Jenny kick him?”

“It was her brother’s dog,” I said.

“If it were my dog, I’d have done worse,” my father said.

“If it were my dog, I’d have put a firecracker in Peter’s pants,” Finnie said.

“I’d have put a nuclear bomb in Peter’s pants,” my father said.

Finnie and my father laughed. He appeared to have forgotten who Finnie’s father was. The two of them were talking like they were old friends. Even after my mother cleared away the dishes, they made no move to leave the table. Finally my father looked at the clock and stood up. “Well, I suppose it’s about that time.” That was what he said whenever he had to go to work.

“What time?” Finnie asked.

“Time to go to work,” I said.

“Now?” Finnie apparently did not know that people worked at night.

My mother handed my father his lunch box and he left.

Later, as Finnie was leaving, he thanked me for having him over. “A lot of people don’t like me because of my dad.”

“Why?” I didn’t see why that should have anything to do with it.

“I don’t know,” Finnie said. “Your dad is nice. He looks awfully tired, though.” Finnie stepped out the door and got on his bike. He smiled and rode up the street toward his house.

I closed the door and thought about what he’d said. My father definitely was nice. He often looked tired too, that was true, but that evening he’d looked especially tired.

Recenzii

"A terrific first novel, brilliantly conceived and inventively executed, with a power house of an ending that resonates long after the book is finished — a stunning accomplishment from a young writer who deserves a close look."

— Quill & Quire

"An eminently readable and warmly witty debut with a seamless narrative and a sucker-punch ending."

— Georgia Straight

— Quill & Quire

"An eminently readable and warmly witty debut with a seamless narrative and a sucker-punch ending."

— Georgia Straight

Cuprins

First Period

Second Period

Third Period

Overtime

Second Period

Third Period

Overtime