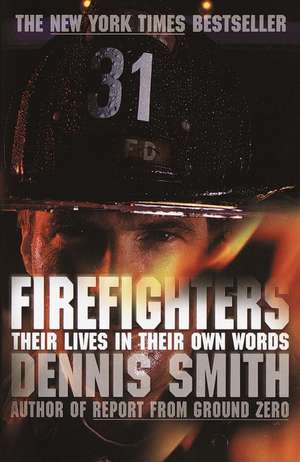

Firefighters: Their Lives in Their Own Words

Autor Dennis Smithen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2002

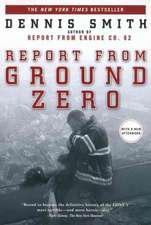

Dennis Smith, author of Report from Engine Co. 82, traveled across the country talking to dozens of America’s firefighters to put together this powerful collection of their own descriptions of their most dramatic and intense experiences on the job. Their stories, compiled here, are timeless testimonies to the human capacity for heroism and nobility.

Focusing on the most courageous firefighters, from those who have been decorated for heroism to those who have been seriously injured, Firefighters presents the extraordinarily rich and rugged voices of men and women who fight urban building fires, who battle sweeping forest fires, who perform emergency rescues, and who face extreme danger and risk as part of their everyday lives. Sometimes brave, sometimes funny, sometimes bittersweet or filled with anger, these voices combine to make Firefighters both a riveting adventure drama and a moving chronicle of American heroism at its finest.

Preț: 114.19 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 171

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.85€ • 22.87$ • 18.08£

21.85€ • 22.87$ • 18.08£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767913072

ISBN-10: 0767913078

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 8 PAGE B/W PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767913078

Pagini: 352

Ilustrații: 8 PAGE B/W PHOTO INSERT

Dimensiuni: 131 x 203 x 19 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

Dennis Smith grew up in the tenements of New York's East side. After a stint in the U.S. Air Force, he was appointed to the New York Fire Department. An active firefighter for 18 years, he retired to become the publisher and editor in chief of Firehouse Magazine, a Honorary Deputy Chief of the New York City Fire Department and Chairman of the New York Academy of Art. He has written several books about firemen, four of which have been New York Times bestsellers, including Report from Engine Co. #82, and Firefighting in America. He is also the author of the novels, The Final Fire, Glitter and Ash, and Steely Blue.

Extras

Training and First Fare

When I got called for the fireman’s job, I was sent to the fire department training school to learn all the things you have to know to be a professional firefighter.

The training school confronts you with a lot of tough situations. They put you in really heavy smoke without masks, so you get a sense of what it’s like to be in a terribly hostile environment, one that’ like claws around your neck, just squeezing and squeezing. You get an understanding of what it’s like to work in complete darkness, where you’re totally blind. This is what it’s like to be in a burning building, you learn.

You’re also taught many other things. You learn how to use the equipment, the fire trucks, the Halligan tool (it’s a pry bar with a fork on one end and a point and adz on the other), the axes, the claw tools, and hooks. You’re taught how to use hoses and nozzles, how to stretch hose, hump hose, pack hose. You learn the science of fire. You learn how fire travels. You learn the various kinds of building construction. You know what kind of windows to expect in different buildings, and you know how to deal with those windows and whether to break them or not.

In a way, it’s like studying to be a lawyer or a doctor. In law school, the student studies law books, goes through mock trials, and says, ”Hey, I really know what I’m doing.” Then he finds it’s a lot different when he’s in an actual courtroom. The medical student studies chemistry, physiology, anatomy, and how to use a scalpel. But once he gets into an actual operating room, it’s different–suddenly people’s lives are at stake. It’s no longer an academic confrontation. It’s right now.

It’s the same thing with a firefighter. You learn all these things in training school so that when you are out in the field in an emergency situation, you know where to go and what to do, so that your actions will be effective.

Here I was, a trained firefighter. I got assigned to a firehouse in Queens. The men I worked with there were great guys, what we call stand-up guys. They had fast lips, they could get around any situation with their mouths when they couldn’t do it with their dukes. You meet all kinds of personalities in a firehouse. They’re all fundamentally good guys who care about other people. That, in my opinion, is what sets them apart. That’s not to say that you have a room full of Francis of Assisi types figuring out how they’re going to help the poor. But in an emergency situation they care about what happens to people.

I got to the firehouse, met these guys. Then, of course, the alarm started ringing. So I went through a few alarms. Maybe it was a false alarm, a garbage pail on fire, a car accident, maybe somebody went out to get a paper and left on the stove. All of these things can happen.

I remember the first fire. Not a really great fire, but there were a couple of things that happened that day that stick in my memory. The area outside is called the apron. When the fire trucks are coming out, the two firemen are out there stopping traffic. In those days two firemen rode on the back step of the fire engine. We don’t do that anymore because it’s unsafe.

I remember being on the back of the rig, it’s two in the afternoon and I’m putting on my coat, with one arm in the D-ring hanging there like a subway strap. The truck is stopped momentarily, waiting for the traffic to halt. I look up, and who walks by but a priest from St. Mary’s parish up by Queens Boulevard. He looks over, and he blesses me and the guy beside me on the back of the truck. Now, the other guy may be an atheist for all I know, but I have this priest blessing me, so I make the sign of the cross, a conditioned response like a dog salivating to a stimulus.

We get going, and I’m thinking, “What’s going on here? I’m just doing my job, and this priest is blessing me on the sidewalks of New York.” I guess in his head he’s saying, these guys have a tremendously tough job and they might be in a bit of trouble, so I’ll bless them. But at that point I don’t want anybody reminding me that I might be in trouble. All I know is that I’ve been blessed, and that we are going to this alarm.

From blocks away I could smell the wood burning. It has a particular smell, not like a car fire, for instance, which has a heavy smell of plastic and rubber. This was a two-story frame building in a row of houses typical of that area of Queens, generally lived in by working-class people. It could have been Archie Bunker’s house, because they filmed the introductory sequence to that TV show in this neighborhood.

The first thing I thought of, what every firefighter thinks of, was: “is there anybody inside, how bad is the fire, and what is the immediate thing to do?” One of the saving things about being a trooper in a war is that there is leadership you can rely on, and in the fire department we have a lieutenant or a captain on every truck. I was probably with the captain, Captain Finnegan, because I was a probationary firefighter, and they always put a probie with the captain so the captain can keep an eye on him and assess his performance. The captain has to make reports and decide whether he wants to keep him or transfer him after six months.

I’m in an engine company, and the captain says, “Okay, stretch a two-and-a-half-inch line.” This tells us it’s a serious fire, because for a small fire you stretch a smaller line. This was the way we were trained. So we stretch the hose into the building, and I’m still thinking that I’m probably in better shape than the other because I was blessed. The ladder company arrives, and they immediately go in and do a search. I don’t remember anybody being caught in the fire, maybe somebody was, but it didn’t matter to me at the time. I had my job to do.

We’re on our stomachs, crawling into this fire, and I’m humping, pulling, this gargantuan snake of a hose filled with water. Fifty feet of it weighs ninety pounds when it’s dry, so you can imagine how much it weighs when it’s filled with water. There is a black, dense smoke, and we can’t see an inch in front of us. There’s a red glow in the background, and we’re pushing toward it. Without masks. Making it a “snotty” fire, that’s one where for every square inch of smoke you ingest a square inch of something else comes out of through your eyes, nose, and mouth.

The red glow is in the back of the building, and we learn later that the fire has gone out through the back windows and is shooting up to the afternoon sky. We’re on our stomachs, the guy on the nozzle, myself, and the captain behind me, advancing slowly into the fire. Then all of a sudden, this big guy, another firefighter, comes in and jumps on top of the hose, he grabs it from the hands of our nozzle man, and he runs with in in a crouch toward the red glow. Apparently we’re not moving fast enough for him for some reason.

None of us have smoke masks or SCBAs (self-contained breathing apparatus), so we're all choking. Then we start cursing, "Hey, what the hell is this guy doing?" And our nozzle goes running after the guy, following the string of hose that's dancing in front of him. This big guy pulls up maybe fifteen feet, throws himself on the floor, opens the nozzle, and hits the ceiling. The red glow darkens to blackness. He has stopped the fire. It's amazing, you can have a whole big room on fire, and a two-and-a-half- inch hose will put it out in twelve seconds.

My captain was really mad. He said, "What the hell are you doing?"

And the guy said, "Listen, I got the job done, right?"

Well, the captain let it go. I didn't say anything because I was new on the job. But I felt that this was our line and our hose, and our territory had been infringed on. Later I heard about the old-time firefighters in New York back in the nineteenth century, when the territory was the main thing and there was competition between one firehouse and another. When an alarm came, they'd send one firefighter ahead with a barrel while they got the horses and everything else ready, and he'd slip the barrel over the fire hydrant. And if another gang tried to use it, he'd fight them off. They'd have big fistfights over this hydrant, because the first team to get the water would have control over the fire. But at that first fire of mine I just knew that somehow we should have put out the fire, particularly, I suppose, in view of the fact that I was well protected by the blessing.

What I learned is that it is your job to control the nozzle, and that every fire is a personal confrontation. This is your job, and you have to go in there and put the fire out, and a lot of people are watching you to be assured that the fire is being put out.

Firefighting is a highly coordinated job. You don't begin ventilating a building, for instance, opening windows or doors or breaking windows, until there is water in the hose and the water is shooting out of it. Then you operate in a mathematically correct way. What you're doing is creating pressure inside the room, and the pressure has to have some way of being released, so you break some windows. This is called ventilation. Otherwise, you have the energy of the fire and the energy of the water shooting from the hose, and you have nowhere for all this energy to go. It will just blow back at you toward the door you came in, where there's oxygen. That is what creates flashover fires, when the fire and heat search for oxygen and the fire flashes as it consumes oxygen.

I carried that lesson with me for the rest of my life. The hose is your job, and you have to do the job. If you don't do it and somebody else does, that's hard to live with.

Dennis Smith

When I got called for the fireman’s job, I was sent to the fire department training school to learn all the things you have to know to be a professional firefighter.

The training school confronts you with a lot of tough situations. They put you in really heavy smoke without masks, so you get a sense of what it’s like to be in a terribly hostile environment, one that’ like claws around your neck, just squeezing and squeezing. You get an understanding of what it’s like to work in complete darkness, where you’re totally blind. This is what it’s like to be in a burning building, you learn.

You’re also taught many other things. You learn how to use the equipment, the fire trucks, the Halligan tool (it’s a pry bar with a fork on one end and a point and adz on the other), the axes, the claw tools, and hooks. You’re taught how to use hoses and nozzles, how to stretch hose, hump hose, pack hose. You learn the science of fire. You learn how fire travels. You learn the various kinds of building construction. You know what kind of windows to expect in different buildings, and you know how to deal with those windows and whether to break them or not.

In a way, it’s like studying to be a lawyer or a doctor. In law school, the student studies law books, goes through mock trials, and says, ”Hey, I really know what I’m doing.” Then he finds it’s a lot different when he’s in an actual courtroom. The medical student studies chemistry, physiology, anatomy, and how to use a scalpel. But once he gets into an actual operating room, it’s different–suddenly people’s lives are at stake. It’s no longer an academic confrontation. It’s right now.

It’s the same thing with a firefighter. You learn all these things in training school so that when you are out in the field in an emergency situation, you know where to go and what to do, so that your actions will be effective.

Here I was, a trained firefighter. I got assigned to a firehouse in Queens. The men I worked with there were great guys, what we call stand-up guys. They had fast lips, they could get around any situation with their mouths when they couldn’t do it with their dukes. You meet all kinds of personalities in a firehouse. They’re all fundamentally good guys who care about other people. That, in my opinion, is what sets them apart. That’s not to say that you have a room full of Francis of Assisi types figuring out how they’re going to help the poor. But in an emergency situation they care about what happens to people.

I got to the firehouse, met these guys. Then, of course, the alarm started ringing. So I went through a few alarms. Maybe it was a false alarm, a garbage pail on fire, a car accident, maybe somebody went out to get a paper and left on the stove. All of these things can happen.

I remember the first fire. Not a really great fire, but there were a couple of things that happened that day that stick in my memory. The area outside is called the apron. When the fire trucks are coming out, the two firemen are out there stopping traffic. In those days two firemen rode on the back step of the fire engine. We don’t do that anymore because it’s unsafe.

I remember being on the back of the rig, it’s two in the afternoon and I’m putting on my coat, with one arm in the D-ring hanging there like a subway strap. The truck is stopped momentarily, waiting for the traffic to halt. I look up, and who walks by but a priest from St. Mary’s parish up by Queens Boulevard. He looks over, and he blesses me and the guy beside me on the back of the truck. Now, the other guy may be an atheist for all I know, but I have this priest blessing me, so I make the sign of the cross, a conditioned response like a dog salivating to a stimulus.

We get going, and I’m thinking, “What’s going on here? I’m just doing my job, and this priest is blessing me on the sidewalks of New York.” I guess in his head he’s saying, these guys have a tremendously tough job and they might be in a bit of trouble, so I’ll bless them. But at that point I don’t want anybody reminding me that I might be in trouble. All I know is that I’ve been blessed, and that we are going to this alarm.

From blocks away I could smell the wood burning. It has a particular smell, not like a car fire, for instance, which has a heavy smell of plastic and rubber. This was a two-story frame building in a row of houses typical of that area of Queens, generally lived in by working-class people. It could have been Archie Bunker’s house, because they filmed the introductory sequence to that TV show in this neighborhood.

The first thing I thought of, what every firefighter thinks of, was: “is there anybody inside, how bad is the fire, and what is the immediate thing to do?” One of the saving things about being a trooper in a war is that there is leadership you can rely on, and in the fire department we have a lieutenant or a captain on every truck. I was probably with the captain, Captain Finnegan, because I was a probationary firefighter, and they always put a probie with the captain so the captain can keep an eye on him and assess his performance. The captain has to make reports and decide whether he wants to keep him or transfer him after six months.

I’m in an engine company, and the captain says, “Okay, stretch a two-and-a-half-inch line.” This tells us it’s a serious fire, because for a small fire you stretch a smaller line. This was the way we were trained. So we stretch the hose into the building, and I’m still thinking that I’m probably in better shape than the other because I was blessed. The ladder company arrives, and they immediately go in and do a search. I don’t remember anybody being caught in the fire, maybe somebody was, but it didn’t matter to me at the time. I had my job to do.

We’re on our stomachs, crawling into this fire, and I’m humping, pulling, this gargantuan snake of a hose filled with water. Fifty feet of it weighs ninety pounds when it’s dry, so you can imagine how much it weighs when it’s filled with water. There is a black, dense smoke, and we can’t see an inch in front of us. There’s a red glow in the background, and we’re pushing toward it. Without masks. Making it a “snotty” fire, that’s one where for every square inch of smoke you ingest a square inch of something else comes out of through your eyes, nose, and mouth.

The red glow is in the back of the building, and we learn later that the fire has gone out through the back windows and is shooting up to the afternoon sky. We’re on our stomachs, the guy on the nozzle, myself, and the captain behind me, advancing slowly into the fire. Then all of a sudden, this big guy, another firefighter, comes in and jumps on top of the hose, he grabs it from the hands of our nozzle man, and he runs with in in a crouch toward the red glow. Apparently we’re not moving fast enough for him for some reason.

None of us have smoke masks or SCBAs (self-contained breathing apparatus), so we're all choking. Then we start cursing, "Hey, what the hell is this guy doing?" And our nozzle goes running after the guy, following the string of hose that's dancing in front of him. This big guy pulls up maybe fifteen feet, throws himself on the floor, opens the nozzle, and hits the ceiling. The red glow darkens to blackness. He has stopped the fire. It's amazing, you can have a whole big room on fire, and a two-and-a-half- inch hose will put it out in twelve seconds.

My captain was really mad. He said, "What the hell are you doing?"

And the guy said, "Listen, I got the job done, right?"

Well, the captain let it go. I didn't say anything because I was new on the job. But I felt that this was our line and our hose, and our territory had been infringed on. Later I heard about the old-time firefighters in New York back in the nineteenth century, when the territory was the main thing and there was competition between one firehouse and another. When an alarm came, they'd send one firefighter ahead with a barrel while they got the horses and everything else ready, and he'd slip the barrel over the fire hydrant. And if another gang tried to use it, he'd fight them off. They'd have big fistfights over this hydrant, because the first team to get the water would have control over the fire. But at that first fire of mine I just knew that somehow we should have put out the fire, particularly, I suppose, in view of the fact that I was well protected by the blessing.

What I learned is that it is your job to control the nozzle, and that every fire is a personal confrontation. This is your job, and you have to go in there and put the fire out, and a lot of people are watching you to be assured that the fire is being put out.

Firefighting is a highly coordinated job. You don't begin ventilating a building, for instance, opening windows or doors or breaking windows, until there is water in the hose and the water is shooting out of it. Then you operate in a mathematically correct way. What you're doing is creating pressure inside the room, and the pressure has to have some way of being released, so you break some windows. This is called ventilation. Otherwise, you have the energy of the fire and the energy of the water shooting from the hose, and you have nowhere for all this energy to go. It will just blow back at you toward the door you came in, where there's oxygen. That is what creates flashover fires, when the fire and heat search for oxygen and the fire flashes as it consumes oxygen.

I carried that lesson with me for the rest of my life. The hose is your job, and you have to do the job. If you don't do it and somebody else does, that's hard to live with.

Dennis Smith

Descriere

Now in paperback, bestselling author Smith gives readers a riveting chronicle of American heroism at its best. "Firefighters, " a powerful collection of stories as told by some of America's most decorated firefighters, is an unforgettable journey through the daily lives of these courageous men and women.