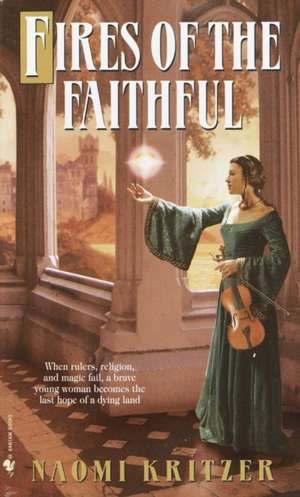

Fires of the Faithful

Autor Naomi Kritzeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2002

Fires of the Faithful

For sixteen-year-old Eliana, life at her conservatory of music is a pleasant interlude between youth and adulthood, with the hope of a prestigious Imperial Court appointment at the end. But beyond the conservatory walls is a land blighted by war and inexplicable famine and dominated by a fearsome religious order known as the Fedeli, who are systematically stamping out all traces of the land’s old beliefs. Soon not even the conservatory walls can hold out reality. When one classmate is brutally killed by the Fedeli for clinging to the forbidden ways and another is kidnapped by the Circle--the mysterious and powerful mages who rule the land--Eliana can take no more. Especially not after she learns one of the Circle’s most closely guarded secrets.

Now, determined to escape the Circle’s power, burning with rage at the Fedeli, and drawn herself to the beliefs of the Old Way, Eliana embarks on a treacherous journey to spread the truth. And what she finds shakes her to her core: a past destroyed, a future in doubt, and a desperate people in need of a leader--no matter how young or inexperienced....

Preț: 51.35 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 77

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.83€ • 10.68$ • 8.26£

9.83€ • 10.68$ • 8.26£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553585179

ISBN-10: 0553585177

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 140 x 176 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Spectra Books

ISBN-10: 0553585177

Pagini: 400

Dimensiuni: 140 x 176 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Spectra Books

Extras

Chapter One

Mira arrived at the Verdiano Rural Conservatory for the Study of Music the same week that the song did. In retrospect, if either Mira or the song had appeared alone, I might have understood things sooner. But I was distracted from the song by my new roommate, and dis- tracted from Mira by the puzzle of the song, and I didn’t learn the truth about either one until it was too late to do anything but try to contain the damage.

When I heard that the conservatory had taken on a new student, a sixteen-year-old girl, I knew she’d be placed with me. My old roommate, Lia, had left Verdia with her family months ago, tired of famine and war. I’d gotten rather accustomed to the extra space, and the Dean would be pleased to remind me that it wasn’t really mine. Sure enough, I returned after ensemble practice to find the stranger in my room, her meager possessions strewn over the bed I’d reluctantly cleared for her. She had her back to me, and as I paused in the doorway before saying hello, I realized that she was trying to light a candle with flint and steel by striking them over the wick.

“You’re never going to get it lit that way,” I said. I startled her more than I meant to; the flint and steel skittered across the stone floor and she whirled around to face me. I held out my hands, one empty, the other holding my violin case. “I assume you’re my new roommate,” I said. “My name is Eliana.”

Her eyes flicked past my shoulder, just for an instant, looking to see if there was anyone behind me. Then she looked me over, her gray eyes taking in my short hair, square jaw, shapeless gray robe. I’m very tall for a woman, almost as tall as most men. I’d heard that the boys called me stuck-up; I knew that many people at the conservatory found me a little intimidating. As my new roommate sized me up, I had the eerie sense that she . . . approved.

“My name is Mira,” she said, and gave me brief flash of a smile. “I’m pleased to meet you.” She ducked to pick up the flint and steel.

I hung up my cloak and put away my violin. There was a violin case on Mira’s bed as well, tightly buckled and dusty from the road. “You play violin?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

I hoped she was decent with her instrument; sharing a room at a conservatory with a bad musician could be almost unbearable.

Having retrieved the flint and steel, Mira held them out to me. “Please, would you show me how to use these?”

I took the flint and steel out of her hands and set them on her bed, then scraped some lint off my robes. “You need something that lights easily to catch the spark. These robes they make us wear must be good for something, right?” I glanced up and she smiled cooperatively. I put the lint in the cupped edge of the candle holder and lit it with a spark from the flint and steel, then lit the candle from the burning lint. “There you go.”

“Thank you,” Mira said, and set the candle in the windowsill. It would blow out in a minute or two. She really had no idea how to deal with a candle.

I studied Mira in the flickering light. She had some of the palest skin I’d ever seen, she couldn’t have come here from a farm. But she was well fed, given the famine, she couldn’t have come from any town in Verdia. She was clearly my age, too old to be just starting at a conservatory, but her hair was freshly cut, she couldn’t have transferred from a conservatory in another province. But it was the candle that really had me puzzled.

I was always reasonably adept at magery, probably because playing the violin had honed my ability to concentrate. I couldn’t draw magefire down from the sky to melt stone, of course, I wasn’t Circle material, but I could light a hearth fire from damp wood with a moment’s effort, which impressed most people well enough. Still, even a child could kindle witchlight to light a dim room, or, if she didn’t want the distraction of keeping the witchlight glowing, she could light a candle with her cupped hand. Even my half-wit friend Giula could do that much. There were people who couldn’t use magery, but very few, and they would have already known how to light a candle the hard way. The only real reason I could think of that Mira might avoid using magery would be if she were trying to conceive a child. Using magic decreased fertility; that’s why my mother had taught me how to use flint and steel, even though childbearing was the farthest thing from my mind at the conservatory. I wondered why Mira’s mother hadn’t taught her the same thing; maybe Mira’s mother was one of those women who had children whether she used magery or not.

The wind blew out the candle and I watched as Mira fumbled for a moment before she managed to get it lit again. I set it down on the table beside her bed.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

“Cuore,” Mira said. Then she hesitated for a moment and added, “Most recently.”

“Cuore?” Whatever answer I’d imagined, that wasn’t it. I tried to hide my surprise. “How are things up there? They say the famine is affecting everyone . . .”

“Not Cuore.” A sardonic smile flashed across Mira’s face. “The home of the Circle, the Fedeli, and the Emperor will always stay well supplied.” She turned away to hang up her cloak on a peg by the foot of her bed. “How are things here?”

“Not too bad, not at the conservatory. This part of Verdia didn’t see any fighting during the war; my friend Bella and I used to go up to the top of the bell tower to look at the countryside beyond Bascio, and we never saw so much as smoke, let alone magefire. Food was a little short during the war, but at least it grows here now. The famine areas are closer to the Vesuviano border, where the fighting was, we don’t waste much, but we don’t go hungry, either.”

Mira picked up her violin and moved it to her desk. “Is it true what I’ve heard?” she asked, her back to me. “About the seeds?”

“That the seeds die in the ground without even sprouting?” I sat down on my own bed, staring at Mira’s back. “Yes. At least in the worst areas.”

“Where are you from?” Mira asked.

“Doratura,” I said. “It’s west of here, but nowhere near the famine areas. Don’t worry, my family is fine.”

“That’s good,” Mira said, turning toward me again and sitting down on her stool.

“There are others here who aren’t as fortunate,” I said. “My friend Bella, her family’s farm isn’t in the truly devastated area, but everything they plant grows stunted, and withers in a strong sun.”

Mira was silent, rubbing the edge of one sleeve with her fingers.

“If you are from Cuore ‘most recently,’ where were you from originally?” I asked.

“Tafano,” Mira said. “It’s a very small village south and west of here. I wouldn’t expect you to have heard of it.”

I blinked. “How did you end up in Cuore? And what are you doing back in Verdia?”

“I thought I had a calling.” Mira studied her hands. “My order was pretty obscure, and I had to go to Cuore to go to seminary.”

“You’re a priestess?” I said.

“No,” she said. “I was only ever an initiate. I didn’t get as far as the ordination, and now, obviously, I’m never going to.” She looked up to give me a rueful smile. “I decided I wanted to pursue my first love, music. I came here because, well, I was born in Verdia. I felt like I belonged here.”

I shook my head. Starting at a conservatory so late, she couldn’t possibly have been sponsored by the Circle with a scholarship, she had to be a paying student. I was curious to know where she’d gotten the money, but it would have been too rude to ask. I wondered if she’d stolen it from her order; the Dean was unlikely to inquire too carefully regarding the source of any silver crossing his desk.

“Eliana!” There was a sharp rap at my door. “Are you in there?”

“Come in,” I called.

Giula flung the door open. “You were going to come meet me, weren’t you? To practice? Remember?”

“I’m sorry,” I said. I hadn’t forgotten; I’d just decided that Giula could wait. “Giula, this is my new roommate, Mira. Mira, this is Giula, one of the other violinists.”

“Oh!” Giula’s indignation melted; a newcomer was certainly excuse enough to be late to a practice session. “How nice to meet you.” She smiled at Mira, showing her dimples. “Where are you from?”

“Tafano,” Mira said.

“Tafano!” Giula actually seemed to recognize the name of the village. “Where ever did you get lovely pale skin like that in Tafano?”

“Well, most recently I lived in Cuore,” Mira said.

Giula’s eyes bugged out.

I grabbed Giula’s arm. “Did you want to practice, or not?” I asked. Giula shot me a venomous glare, but let me drag her off. “It’s not like she’s going anywhere,” I said once the door was closed. “You can interrogate her later.”

Giula was cheerful again by the time we’d reached the practice hall. “So that’s your new roommate! Not quite so bad as you made it sound at lunch, is it?”

“I still say there are enough empty rooms that I shouldn’t have to have a roommate if I don’t want one,” I said. Giula shrugged unsympathetically. In the practice room, Giula and I set our music on the stand. We would play a duet in the autumn recital the following week; I was a better violinist than Giula, but we shared a teacher, Domenico, and he had instructed us to play together. She would take the easier part.

“Did she tell you why she came here from Cuore?” Giula asked, still incredulous.

“She was in Cuore preparing for ordination,” I said.

“She was going to be a priestess? But why would she ever come back here?”

“You can ask her later, can’t you?” I flipped open the music to the duet. “Are we going to practice or not?”

Giula tightened her bow and started tuning her violin, still talking. “And why would she be starting at this time of year? Auditions were in the spring. Though she couldn’t have auditioned anyway, she’s our age, or maybe even older. She has to be a paying student. But why would you pay to come here?”

I rolled my eyes and tucked my violin under my chin.

“Maybe her family lives near here,” Giula said.

“Maybe.” Students who left the conservatory, even for a day, lost their scholarships and could not return. We assumed it was to discourage all but the most dedicated from pursuing a life as a musician. But our families could come and visit us, which was a possibility if they lived close by. Lia’s family had visited once. “We need to work on this duet,” I said. At least Giula needed to work on it, because if she didn’t sound at least decent at the recital, nobody would notice my playing at all.

Giula reluctantly tucked her violin under her chin. “Why do you suppose she’s so pale?”

“Presumably she spent most of her time indoors at her seminary,” I said. Giula started to lower her violin again, and I tapped the music pointedly. “Let’s take it from the top.”

I counted out a beat and started to play. Giula picked up her part in the third measure, and stumbled almost immediately.

“Again,” I said. “Start here.”

“Wait,” Giula said.

For a moment, I thought Giula was going to start gossiping again, but her head was tilted to the side, and after a beat I realized that she was listening to the musician in the next practice room. The musician was Celia, one of the sopranos; I recognized her voice. But she wasn’t practicing anything I’d heard before, and since Celia was at least nominally a friend of mine, I was familiar with most of her repertoire.

I’ve come to wed your father but I want to make you mine.

If you’ll take me as your mother, you will find my faults are few.

I’ve brought a gift of honey, bright as sun and sweet as wine.

And as pure as all the love I hold inside my heart for you.

Celia paused, and Giula looked up at me, her eyes wide. “Everyone’s talking about this song. I hadn’t heard it sung yet.”

Celia began to sing the verses. Six children tasted the honey and embraced their stepmother. Then the seventh son rejected the honey, and was murdered by his own father for his insolence. Then one by one the other six children died, poisoned by the lethal gift. In the end, the father wept over the graves of his children, but was at the mercy of his new wife and his two stepchildren. In the final verse, the bones of the dead children cried out for vengeance; apparently this was left up to the listener.

There was a knock on the door of our practice room. I opened the door; it was Bella, her trumpet in her hand. “Did you hear Celia?” she asked.

I sighed. “I gather we aren’t the only students here who aren’t rehearsing.”

Bella waved her hand, not the one with the trumpet, dismissively. “I think I saw the person who brought the song.”

“Really?” Giula set her violin down altogether. I resigned myself to the inevitable and put mine down as well.

Bella sat down on one of the practice stools, and Giula and I did as well. “I was watching down the hill for the messenger wagon, and I saw someone ride into town. I don’t know horses that well, but it looked like a fast riding horse, not the sort of horse you’d hitch to a plow. The rider was wearing a cloak pulled over his face, “ Bella gestured with the floppy sleeve of her robe.

“It’s been a chilly autumn,” I said. “Of course he wanted to protect his face.”

Bella rolled her eyes. “I saw him dismount by the cottage where your teacher lives, Domenico. He was inside for less than an hour, and then he rode away.”

“Did you see his face?” Giula asked.

“It would have been too far even if his face hadn’t been covered,” Bella said. “You should try asking Domenico about it.” She shot a glance directly at me. Domenico would never gossip to Giula, not when she was so busy flirting with him, but he might talk to me. I nodded a little. It was worth a try.

“What do you think the song’s about?” Giula asked.

“It’s probably some stupid noble’s feud,” Bella said. “Some branch of the family got killed by treachery and now they want the whole world to help them get revenge.”

“Wouldn’t it help if the offending family were named?” I asked.

“People might not spread the song if they knew it was some petty feud,” Bella said.

“They would if it was a good enough tune.”

“So what’s your theory?” Bella asked.

“I don’t know. I don’t think the poisoned honey refers to literal honey, though. I think it’s some sort of disguised danger, but it’s disguised awfully well. I don’t have any idea what it’s talking about.”

Giula didn’t even venture a guess. “I wish it had been the messenger service, instead of a man with a mysterious song,” she said.

“Honestly, so do I.” For a moment, Bella’s face looked worn. “The news from my family last time wasn’t good.” The news next time was unlikely to be better, but anything was preferable to uncertainty. And perhaps the harvest would be better than expected, if only by a little.

The supper bell rang, and we quickly packed up our instruments to walk over to the girls’ meal hall. I had expected Mira to join us for supper, but she wasn’t there. Celia was, though, repeating the words of the honey song to those who hadn’t heard them yet. Giorgi, the cook’s assistant, brought out heavy tureens of stew made from the vegetables we grew in the conservatory garden, and jugs of tea and wine.

Celia flicked back a curl that had fallen into her face and took a sip of her tea. Celia didn’t like tying her hair back, probably because the curls framed her heart-shaped face so charmingly. Not that any of us were supposed to be trying to attract the attention of the boys, but Celia liked any attention she could get. “It’s a lovely song,” she said, “but I think it’s just about some feud. Some noble family sent a bride to another family with poisoned honey. Their children ate it and died. Maybe there was a son who refused to eat it, but, “

This wasn’t far off from Bella’s theory, but her eyes narrowed. “Oh, come on, Celia,” she said. “You don’t really think the song is about literal honey, do you?”

Celia arched one perfect eyebrow. “Why don’t you share your theory with us, Bella?” she said.

“Eliana thinks the poisoned honey is a symbol for some disguised danger,” Bella said. “I think she’s right, but I don’t know what the danger is.”

Flavia, a percussionist, looked up from her stew. “I think you’re right about the symbolism,” she said. “It’s a ballad rhythm, or I’d say that the Fedeli wrote the song.”

“The Fedeli.” I put down my tea. “Why the Fedeli?”

“Don’t you think the ‘poisoned honey’ could refer to a heresy of some kind?” Flavia said. “I could easily see the song reaching us well before we actually heard what heresy it was supposed to be about.”

We considered that idea for a moment.

“But, like I said, the rhythm’s not right. I would expect the Fedeli to write something that sounded like a hymn, not like something that sounds like a folk ballad.” Flavia took a sip of wine.

“Eliana got a new roommate today,” Giula said. “From Cuore.”

That diverted the conversation entirely, and after checking to make sure that she wasn’t standing behind me, I described Mira to the others and told what little I knew about her: born in Tafano, trained at a seminary in Cuore, and ignorant in the use of candles.

“Do you suppose . . .” Bella said.

“Why would you come all the way to the conservatory from Cuore if you were going to try to get pregnant?” I asked. Any pregnant girl student, and any boy student who was named as the father, was expelled from the conservatory. Clearly, if the Lady blessed your union, she wanted you to get married and settle down, not go off to join an ensemble.

“Maybe she’s in love with one of the boy students,” Giula said.

“How would she have met him?” I asked. We were kept well separated from the boys at the conservatory. The only place we were even allowed in the same room with them was the chapel. This encouraged a high degree of religious observance among girls like Celia.

“That can’t be it,” Bella said. “Maybe she had a lover in Cuore, and she hopes she’s pregnant by him.”

“Why would she have left, then?” Giula asked.

“That’s obvious,” Bella said. “She was an initiate, wasn’t she? Maybe the boy wasn’t.”

“Still,” I said. “Why would she leave Cuore?”

“Maybe . . .” Bella closed her eyes and rubbed her forehead. “This is getting too complicated. Even if the relationship ended badly, if she has any reason to think she’s pregnant, then coming back to Verdia would just be stupid.”

Celia tossed her hair back. “Clearly, you’ve never been in love.”

Bella’s eyes narrowed and she smiled slowly at Celia, letting Celia’s words hang in the air as a pink flush crept slowly upward from the gray wool collar of Celia’s robe. “If I risk being expelled from the conservatory,” Bella said, “I want it to be for a man, not a boy. But to each her own.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Celia said.

Bella had started to turn back to her tea, but when Celia got defensive, she took that as an invitation to twist the knife a little more. “Why would it mean anything?” she asked. “I think your devotion to the Lady is very touching, Celia.”

Celia went white. Naturally, she attended chapel daily to flirt with the boys there, but Bella meant something else, and Celia knew it. Magery was the Lady’s gift to humanity, but it decreased fertility. To counteract this tendency, the Lady encouraged Her children to try to make children of their own as frequently as possible. Of course, the Lady didn’t want conservatory students having babies, our celibacy, like the sterility of the Circle, increased the fertility of everyone else. But, still. “Honoring the Lady” was a popular euphemism for the sort of thing that happened secretly on summer nights in the shadows of the practice halls, and that occasionally resulted in expulsions.

“The Lady rewards those who love Her with their whole heart,” Celia said, her voice shaky and her face still white. “You should try attending Chapel sometime when it isn’t required, Bella. The results might surprise you.”

“Sure, Celia,” Bella said, and returned to her tea. Celia stood up to go, and Bella caught her by the dangling edge of her sleeve. “Just be careful,” she said. “You know what I mean.” She released Celia, clucking her tongue, and Celia flounced out.

I tried to imagine Mira with a lover, and shook my head. Mira lacked the coy flirtatiousness it took to catch a boy’s eye. She was like me, a little bit intimidating. Besides, if she’d stopped using magery that long ago, why wouldn’t she have learned to light a candle by now?

Mira was not in the room when I returned from supper, but her cloak and violin were missing. She’d gone somewhere to practice, late though it was. She’d taken the candle. I slung my own violin over my shoulder and went out to see if I could find her. I was curious how well she could play, after all these years as a seminarian.

I listened carefully to the muffled cacophony in the corridor of the main practice hall. Two violins, but I recognized both. Not Giula, unfortunately, she needed the practice, but was probably studying for our music theory class.

I left through the back door, and as I crossed the courtyard, I saw the flicker of candlelight in the north practice hall. Many students used candles rather than witchlight while they practiced, but none of us used the north practice hall. It was cold, first of all, and so drafty that small drifts of snow actually blew across the floor in winter. And the acoustics were terrible. Bella once claimed it was haunted, though she was telling a ghost story to scare Giula and needed a creepy setting for it. In any case, the candle had to belong to Mira.

The front door of the north practice hall was ajar. I slipped in and paused in the shadow. Mira was playing in the ensemble hall rather than one of the side rooms; she had set her candle in a wall niche that protected it from drafts, but it still wavered, making her shadow dance on the wall. It occurred to me that sneaking around to spy on another student practicing was a little absurd, but I was curious about Mira. I put down my violin very quietly, sat with my cloak huddled around me, and listened.

Mira started off with very basic études, finger exercises. Her fingers were clumsy, and she missed many of the notes, which wasn’t surprising for someone who’d spent the last few years in a seminary rather than a conservatory. But as she warmed up and the fluidity began to come back to her, she began to make the études sound like something I hadn’t expected. She treated them as if they were music rather than a demonstration of technical skill; I realized, listening to her, that the world was slipping away around her, and nothing but each note existed. Her technique was raw, but the sound was beautiful. I wondered how she was able to bring herself to give this up, when she thought she had a calling, and if her calling was so powerful, how she had been able to give that up, now.

Then she finished with her exercises and began to play a melody, and I froze.

There were a few songs once used in old village ceremonies that still circulated at the conservatory. Playing ritual music from the Old Way was illegal, of course. And it would have been dangerous in a city conservatory, because of the Sudditi Fedeli della Signora, the Faithful Subjects of the Lady. But the Fedeli avoided backwater areas like Verdia, and most everyone shrugged off the danger. I certainly did. I knew a wedding song and a healing song, and I played them regularly. The Old Way music had an undercurrent that more recent music completely lacked. Most Old Way songs were in a minor key, but they were fast, with rhythms that felt like the heartbeat of the earth underneath me, and they stirred my blood like strong wine and cold wind.

I had never heard the song Mira was playing, but I recognized it as Old Way music from the peculiar rhythm: da dat da da dat da wham wham wham. Da dat da da dat da wham wham wham. Listening intently, I could see Mira throw her head back as she played, raising the violin like an offering, and I thought, she was studying to be a priestess?

Mira played the song through twice, picking up the tempo as she played. A cold draft touched my feet where I sat, and I curled my toes up inside my boots, clenching and flexing my hands. Then, midphrase, Mira stopped. She set her violin down carefully on the floor, and straightened for a moment, looking at the candle. Then she bent over and vomited on the floor, and vomited again, and then fell to her knees, still retching. I jumped to my feet. “Mira!”

She should have been startled by my presence, but she didn’t even look up. When I reached her, she was curled up on the cold stone floor, clenching her fists and wrapping her arms around herself. “I’ll get the physician,” I said.

“No,” she gasped, and grabbed the edge of my robe in her fist. “No, it won’t do any good. Stay here. Don’t leave me. This will pass. It will pass.”

I didn’t believe her, but I was afraid she might be dying, and she might die alone if I left her. So I dragged her away from her vomit on the floor, then covered her with her cloak and sat down beside her. She was shaking harder than I’d ever seen anyone shake from cold. After a moment I covered her with my own cloak, as well.

“I’ll be fine,” she said, between spasms of shaking. “Don’t worry about me.”

“Lady’s tits, Mira,” I said. “Let me get the physician. Or Giorgi, the cook’s assistant, he’s the village healer.”

“No,” she said. “I just want you. Stay with me. Please, don’t leave me.”

“But I don’t know anything about healing,” I said. I touched her forehead with the back of my hand to test for fever, but it was cool, even chill.

“I don’t need healing,” she said. “Talk to me.”

“What do you want me to talk about?” I asked.

“Anything,” she said. “Just let me hear your voice, so I know I’m not alone.”

So I talked. I told her about my family, about my favorite brother, the second-oldest, Donato, who taught me to fight and used to make me clay whistles. I told her about my friends at the conservatory, Giula and Bella and Flavia and Celia. I told her about the song that had arrived so mysteriously, about poisoned honey and dead children. I told her about my teacher, Domenico, how he was one of the handful of great teachers still left at the conservatory. Domenico had been educated at the Central Conservatory in Cuore and had actually spent several years playing at the Imperial Court before he gave it all up to come live in Verdia and teach at our conservatory. No one really knew why. Domenico told me he’d hated court, and from his descriptions of it I could understand why, though I still dreamed of playing there myself.

Mira shuddered, but this time she didn’t stop. Her eyes rolled back in her head, and she shook as if invisible hands grasped her shoulders and wrenched her back and forth. I had seen one other person have a convulsion, one of my nieces, when she was a baby and had a high fever. My mother had poured cold water over her and she’d lived. But Mira had no fever; her skin was as cold as the stones underneath us. I grabbed her and tried to hold her still, but her jerks pulled her out of my grasp. Then a moment later it was over, and she lay still. I held my hand lightly over her lips; she was still breathing. I sat back silently, clasping her limp hand. Mira’s hand was like carved marble, cold and impossibly smooth. I rubbed her palm with my thumb and suddenly my own blood turned cold. Mira had no calluses on her hands, not even the sort she’d have had from light garden work.

One of my brothers had trained for the priesthood for a while. He’d given it up after falling in love with a girl in the village, but I clearly remembered his complaints to our mother about the work. The elder priests and priestesses talked a lot about communing with the Lord and the Lady through reaping their bounty, but my brother thought that was just an excuse to stick the novitiates with all the heavy farm chores. I’d grown up on a farm and my brother was no stranger to hard work, but after a year at the seminary his calluses were thicker than my father’s.

I touched Mira’s soft hand again. She had never been an initiate priestess. That whole story was a lie.

Why would she make up a story like that?

I lit a globe of witchlight to get a closer look, and Mira threw her free hand over her face with a groan. “Hurts my eyes,” she muttered. “Put it away.”

I dispelled the witchlight with a flick of my wrist. Mira drew her hand away slowly.

“Play for me,” she said.

Her violin was in reach and in tune, while mine wasn’t, so I picked hers up.

“Play the funeral song,” she said. “The song I was playing earlier. I know you were listening.”

So it had been a funeral song. I added that mentally to my repertoire and began to play. I have always been able to pick out tunes quite easily, and I experimented a little as I played, adding a forceful downstroke to the strong beats and pairing them with the same note an octave up. Domenico had told me to hold still while I played, but Old Way songs always made me want to use my whole body, and I swayed back and forth with the music. I closed my eyes, watching the flicker of the candle against my eyelids. Then I opened my eyes.

For the first crazy instant, I thought a third person had silently entered the north practice hall, dressed in the uniform of a soldier. Then I thought I recognized my own face around the dark, riveting eyes. I started to my feet, and then realized that all I was looking at was a crumbling fresco. This was one of the oldest buildings at the conservatory, and had once been lavishly decorated.

I forced out a laugh. “I’ve been listening to too many of Bella’s ghost stories,” I said. Mira was silent. Slowly, I sat back down on the stone floor, more shaken than I thought I had any call to be. “The candlelight is making me jumpy.”

I set down Mira’s violin and took her soft hand again just as the candle went out.

I stayed beside her through the night, talking when she roused enough to ask to hear my voice. Mira seemed to waver from consciousness to unconsciousness like a sputtering flame, but when she woke she seemed glad to have me there. In the last part of the night, her tremors calmed, and I asked if she’d like me to help her back to the room, where she might be more comfortable. She sat up, still shaking a bit. “Thank you,” she said. “I’d appreciate that.”

I packed up her violin and slung both hers and mine over my shoulder, then wrapped her cloak around her shoulders and slipped my arm under hers. If anyone was out and about at that hour, they were on their own business and pretended not to see us; I helped Mira up the long staircase and into our empty room, then helped her sit down on the bed. Mira lay down and pulled her blanket over herself, closing her eyes. Her shaking had finally eased.

There was an hour or so before I’d have to get up, and I quietly slipped my boots off. As I hung Mira’s cloak up, something fluttered to the floor. I picked it up and kindled a tiny witchlight, hoping that it wouldn’t disturb Mira; it was a letter of some kind. You stupid fools, it said. We don’t want your money. We want our daughter back. I flipped it over; it was signed, Isabella and Marino of Tafano, Verdia. I slipped the letter under a musical score on her desk, ashamed of myself for reading it.

“What?” Mira said, and I jumped, flicking away my witchlight and nearly scattering the papers again. In the darkness, I lay down on my own bed, curling up under my blanket.

“I’m leaving,” Mira said, her voice as clear as the bells we rang at the Viaggio service.

“What?” I said, but Mira went on without heeding me, and I realized that she was talking in her sleep.

“You’re wrong, Liemo,” she said. Her voice was contemptuous. “I’ll break the chains you’ve bound me with. The Lady promises freedom and I’m going to take it. You can lock me up, you can even kill me, but you can’t make me serve you again.”

She was quiet after that, her breathing low and even. I lay awake, shivering. I told myself that I was still cold from the practice hall, but the fierce steel in Mira’s voice had cut me to the bone. I didn’t know whom she was speaking to, or what she was talking about, but I hoped I’d never find myself standing against her. In the end, I didn’t sleep at all that night. At dawn, Mira opened her eyes and looked over at me, giving me a slow smile that warmed me to my feet. “You will keep my secret?” she said.

I didn’t even know what her secret was, but looking into her eyes, I would have done anything for her. “Yes,” I said. “Yes.”

Mira arrived at the Verdiano Rural Conservatory for the Study of Music the same week that the song did. In retrospect, if either Mira or the song had appeared alone, I might have understood things sooner. But I was distracted from the song by my new roommate, and dis- tracted from Mira by the puzzle of the song, and I didn’t learn the truth about either one until it was too late to do anything but try to contain the damage.

When I heard that the conservatory had taken on a new student, a sixteen-year-old girl, I knew she’d be placed with me. My old roommate, Lia, had left Verdia with her family months ago, tired of famine and war. I’d gotten rather accustomed to the extra space, and the Dean would be pleased to remind me that it wasn’t really mine. Sure enough, I returned after ensemble practice to find the stranger in my room, her meager possessions strewn over the bed I’d reluctantly cleared for her. She had her back to me, and as I paused in the doorway before saying hello, I realized that she was trying to light a candle with flint and steel by striking them over the wick.

“You’re never going to get it lit that way,” I said. I startled her more than I meant to; the flint and steel skittered across the stone floor and she whirled around to face me. I held out my hands, one empty, the other holding my violin case. “I assume you’re my new roommate,” I said. “My name is Eliana.”

Her eyes flicked past my shoulder, just for an instant, looking to see if there was anyone behind me. Then she looked me over, her gray eyes taking in my short hair, square jaw, shapeless gray robe. I’m very tall for a woman, almost as tall as most men. I’d heard that the boys called me stuck-up; I knew that many people at the conservatory found me a little intimidating. As my new roommate sized me up, I had the eerie sense that she . . . approved.

“My name is Mira,” she said, and gave me brief flash of a smile. “I’m pleased to meet you.” She ducked to pick up the flint and steel.

I hung up my cloak and put away my violin. There was a violin case on Mira’s bed as well, tightly buckled and dusty from the road. “You play violin?” I asked.

“Yes,” she said.

I hoped she was decent with her instrument; sharing a room at a conservatory with a bad musician could be almost unbearable.

Having retrieved the flint and steel, Mira held them out to me. “Please, would you show me how to use these?”

I took the flint and steel out of her hands and set them on her bed, then scraped some lint off my robes. “You need something that lights easily to catch the spark. These robes they make us wear must be good for something, right?” I glanced up and she smiled cooperatively. I put the lint in the cupped edge of the candle holder and lit it with a spark from the flint and steel, then lit the candle from the burning lint. “There you go.”

“Thank you,” Mira said, and set the candle in the windowsill. It would blow out in a minute or two. She really had no idea how to deal with a candle.

I studied Mira in the flickering light. She had some of the palest skin I’d ever seen, she couldn’t have come here from a farm. But she was well fed, given the famine, she couldn’t have come from any town in Verdia. She was clearly my age, too old to be just starting at a conservatory, but her hair was freshly cut, she couldn’t have transferred from a conservatory in another province. But it was the candle that really had me puzzled.

I was always reasonably adept at magery, probably because playing the violin had honed my ability to concentrate. I couldn’t draw magefire down from the sky to melt stone, of course, I wasn’t Circle material, but I could light a hearth fire from damp wood with a moment’s effort, which impressed most people well enough. Still, even a child could kindle witchlight to light a dim room, or, if she didn’t want the distraction of keeping the witchlight glowing, she could light a candle with her cupped hand. Even my half-wit friend Giula could do that much. There were people who couldn’t use magery, but very few, and they would have already known how to light a candle the hard way. The only real reason I could think of that Mira might avoid using magery would be if she were trying to conceive a child. Using magic decreased fertility; that’s why my mother had taught me how to use flint and steel, even though childbearing was the farthest thing from my mind at the conservatory. I wondered why Mira’s mother hadn’t taught her the same thing; maybe Mira’s mother was one of those women who had children whether she used magery or not.

The wind blew out the candle and I watched as Mira fumbled for a moment before she managed to get it lit again. I set it down on the table beside her bed.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

“Cuore,” Mira said. Then she hesitated for a moment and added, “Most recently.”

“Cuore?” Whatever answer I’d imagined, that wasn’t it. I tried to hide my surprise. “How are things up there? They say the famine is affecting everyone . . .”

“Not Cuore.” A sardonic smile flashed across Mira’s face. “The home of the Circle, the Fedeli, and the Emperor will always stay well supplied.” She turned away to hang up her cloak on a peg by the foot of her bed. “How are things here?”

“Not too bad, not at the conservatory. This part of Verdia didn’t see any fighting during the war; my friend Bella and I used to go up to the top of the bell tower to look at the countryside beyond Bascio, and we never saw so much as smoke, let alone magefire. Food was a little short during the war, but at least it grows here now. The famine areas are closer to the Vesuviano border, where the fighting was, we don’t waste much, but we don’t go hungry, either.”

Mira picked up her violin and moved it to her desk. “Is it true what I’ve heard?” she asked, her back to me. “About the seeds?”

“That the seeds die in the ground without even sprouting?” I sat down on my own bed, staring at Mira’s back. “Yes. At least in the worst areas.”

“Where are you from?” Mira asked.

“Doratura,” I said. “It’s west of here, but nowhere near the famine areas. Don’t worry, my family is fine.”

“That’s good,” Mira said, turning toward me again and sitting down on her stool.

“There are others here who aren’t as fortunate,” I said. “My friend Bella, her family’s farm isn’t in the truly devastated area, but everything they plant grows stunted, and withers in a strong sun.”

Mira was silent, rubbing the edge of one sleeve with her fingers.

“If you are from Cuore ‘most recently,’ where were you from originally?” I asked.

“Tafano,” Mira said. “It’s a very small village south and west of here. I wouldn’t expect you to have heard of it.”

I blinked. “How did you end up in Cuore? And what are you doing back in Verdia?”

“I thought I had a calling.” Mira studied her hands. “My order was pretty obscure, and I had to go to Cuore to go to seminary.”

“You’re a priestess?” I said.

“No,” she said. “I was only ever an initiate. I didn’t get as far as the ordination, and now, obviously, I’m never going to.” She looked up to give me a rueful smile. “I decided I wanted to pursue my first love, music. I came here because, well, I was born in Verdia. I felt like I belonged here.”

I shook my head. Starting at a conservatory so late, she couldn’t possibly have been sponsored by the Circle with a scholarship, she had to be a paying student. I was curious to know where she’d gotten the money, but it would have been too rude to ask. I wondered if she’d stolen it from her order; the Dean was unlikely to inquire too carefully regarding the source of any silver crossing his desk.

“Eliana!” There was a sharp rap at my door. “Are you in there?”

“Come in,” I called.

Giula flung the door open. “You were going to come meet me, weren’t you? To practice? Remember?”

“I’m sorry,” I said. I hadn’t forgotten; I’d just decided that Giula could wait. “Giula, this is my new roommate, Mira. Mira, this is Giula, one of the other violinists.”

“Oh!” Giula’s indignation melted; a newcomer was certainly excuse enough to be late to a practice session. “How nice to meet you.” She smiled at Mira, showing her dimples. “Where are you from?”

“Tafano,” Mira said.

“Tafano!” Giula actually seemed to recognize the name of the village. “Where ever did you get lovely pale skin like that in Tafano?”

“Well, most recently I lived in Cuore,” Mira said.

Giula’s eyes bugged out.

I grabbed Giula’s arm. “Did you want to practice, or not?” I asked. Giula shot me a venomous glare, but let me drag her off. “It’s not like she’s going anywhere,” I said once the door was closed. “You can interrogate her later.”

Giula was cheerful again by the time we’d reached the practice hall. “So that’s your new roommate! Not quite so bad as you made it sound at lunch, is it?”

“I still say there are enough empty rooms that I shouldn’t have to have a roommate if I don’t want one,” I said. Giula shrugged unsympathetically. In the practice room, Giula and I set our music on the stand. We would play a duet in the autumn recital the following week; I was a better violinist than Giula, but we shared a teacher, Domenico, and he had instructed us to play together. She would take the easier part.

“Did she tell you why she came here from Cuore?” Giula asked, still incredulous.

“She was in Cuore preparing for ordination,” I said.

“She was going to be a priestess? But why would she ever come back here?”

“You can ask her later, can’t you?” I flipped open the music to the duet. “Are we going to practice or not?”

Giula tightened her bow and started tuning her violin, still talking. “And why would she be starting at this time of year? Auditions were in the spring. Though she couldn’t have auditioned anyway, she’s our age, or maybe even older. She has to be a paying student. But why would you pay to come here?”

I rolled my eyes and tucked my violin under my chin.

“Maybe her family lives near here,” Giula said.

“Maybe.” Students who left the conservatory, even for a day, lost their scholarships and could not return. We assumed it was to discourage all but the most dedicated from pursuing a life as a musician. But our families could come and visit us, which was a possibility if they lived close by. Lia’s family had visited once. “We need to work on this duet,” I said. At least Giula needed to work on it, because if she didn’t sound at least decent at the recital, nobody would notice my playing at all.

Giula reluctantly tucked her violin under her chin. “Why do you suppose she’s so pale?”

“Presumably she spent most of her time indoors at her seminary,” I said. Giula started to lower her violin again, and I tapped the music pointedly. “Let’s take it from the top.”

I counted out a beat and started to play. Giula picked up her part in the third measure, and stumbled almost immediately.

“Again,” I said. “Start here.”

“Wait,” Giula said.

For a moment, I thought Giula was going to start gossiping again, but her head was tilted to the side, and after a beat I realized that she was listening to the musician in the next practice room. The musician was Celia, one of the sopranos; I recognized her voice. But she wasn’t practicing anything I’d heard before, and since Celia was at least nominally a friend of mine, I was familiar with most of her repertoire.

I’ve come to wed your father but I want to make you mine.

If you’ll take me as your mother, you will find my faults are few.

I’ve brought a gift of honey, bright as sun and sweet as wine.

And as pure as all the love I hold inside my heart for you.

Celia paused, and Giula looked up at me, her eyes wide. “Everyone’s talking about this song. I hadn’t heard it sung yet.”

Celia began to sing the verses. Six children tasted the honey and embraced their stepmother. Then the seventh son rejected the honey, and was murdered by his own father for his insolence. Then one by one the other six children died, poisoned by the lethal gift. In the end, the father wept over the graves of his children, but was at the mercy of his new wife and his two stepchildren. In the final verse, the bones of the dead children cried out for vengeance; apparently this was left up to the listener.

There was a knock on the door of our practice room. I opened the door; it was Bella, her trumpet in her hand. “Did you hear Celia?” she asked.

I sighed. “I gather we aren’t the only students here who aren’t rehearsing.”

Bella waved her hand, not the one with the trumpet, dismissively. “I think I saw the person who brought the song.”

“Really?” Giula set her violin down altogether. I resigned myself to the inevitable and put mine down as well.

Bella sat down on one of the practice stools, and Giula and I did as well. “I was watching down the hill for the messenger wagon, and I saw someone ride into town. I don’t know horses that well, but it looked like a fast riding horse, not the sort of horse you’d hitch to a plow. The rider was wearing a cloak pulled over his face, “ Bella gestured with the floppy sleeve of her robe.

“It’s been a chilly autumn,” I said. “Of course he wanted to protect his face.”

Bella rolled her eyes. “I saw him dismount by the cottage where your teacher lives, Domenico. He was inside for less than an hour, and then he rode away.”

“Did you see his face?” Giula asked.

“It would have been too far even if his face hadn’t been covered,” Bella said. “You should try asking Domenico about it.” She shot a glance directly at me. Domenico would never gossip to Giula, not when she was so busy flirting with him, but he might talk to me. I nodded a little. It was worth a try.

“What do you think the song’s about?” Giula asked.

“It’s probably some stupid noble’s feud,” Bella said. “Some branch of the family got killed by treachery and now they want the whole world to help them get revenge.”

“Wouldn’t it help if the offending family were named?” I asked.

“People might not spread the song if they knew it was some petty feud,” Bella said.

“They would if it was a good enough tune.”

“So what’s your theory?” Bella asked.

“I don’t know. I don’t think the poisoned honey refers to literal honey, though. I think it’s some sort of disguised danger, but it’s disguised awfully well. I don’t have any idea what it’s talking about.”

Giula didn’t even venture a guess. “I wish it had been the messenger service, instead of a man with a mysterious song,” she said.

“Honestly, so do I.” For a moment, Bella’s face looked worn. “The news from my family last time wasn’t good.” The news next time was unlikely to be better, but anything was preferable to uncertainty. And perhaps the harvest would be better than expected, if only by a little.

The supper bell rang, and we quickly packed up our instruments to walk over to the girls’ meal hall. I had expected Mira to join us for supper, but she wasn’t there. Celia was, though, repeating the words of the honey song to those who hadn’t heard them yet. Giorgi, the cook’s assistant, brought out heavy tureens of stew made from the vegetables we grew in the conservatory garden, and jugs of tea and wine.

Celia flicked back a curl that had fallen into her face and took a sip of her tea. Celia didn’t like tying her hair back, probably because the curls framed her heart-shaped face so charmingly. Not that any of us were supposed to be trying to attract the attention of the boys, but Celia liked any attention she could get. “It’s a lovely song,” she said, “but I think it’s just about some feud. Some noble family sent a bride to another family with poisoned honey. Their children ate it and died. Maybe there was a son who refused to eat it, but, “

This wasn’t far off from Bella’s theory, but her eyes narrowed. “Oh, come on, Celia,” she said. “You don’t really think the song is about literal honey, do you?”

Celia arched one perfect eyebrow. “Why don’t you share your theory with us, Bella?” she said.

“Eliana thinks the poisoned honey is a symbol for some disguised danger,” Bella said. “I think she’s right, but I don’t know what the danger is.”

Flavia, a percussionist, looked up from her stew. “I think you’re right about the symbolism,” she said. “It’s a ballad rhythm, or I’d say that the Fedeli wrote the song.”

“The Fedeli.” I put down my tea. “Why the Fedeli?”

“Don’t you think the ‘poisoned honey’ could refer to a heresy of some kind?” Flavia said. “I could easily see the song reaching us well before we actually heard what heresy it was supposed to be about.”

We considered that idea for a moment.

“But, like I said, the rhythm’s not right. I would expect the Fedeli to write something that sounded like a hymn, not like something that sounds like a folk ballad.” Flavia took a sip of wine.

“Eliana got a new roommate today,” Giula said. “From Cuore.”

That diverted the conversation entirely, and after checking to make sure that she wasn’t standing behind me, I described Mira to the others and told what little I knew about her: born in Tafano, trained at a seminary in Cuore, and ignorant in the use of candles.

“Do you suppose . . .” Bella said.

“Why would you come all the way to the conservatory from Cuore if you were going to try to get pregnant?” I asked. Any pregnant girl student, and any boy student who was named as the father, was expelled from the conservatory. Clearly, if the Lady blessed your union, she wanted you to get married and settle down, not go off to join an ensemble.

“Maybe she’s in love with one of the boy students,” Giula said.

“How would she have met him?” I asked. We were kept well separated from the boys at the conservatory. The only place we were even allowed in the same room with them was the chapel. This encouraged a high degree of religious observance among girls like Celia.

“That can’t be it,” Bella said. “Maybe she had a lover in Cuore, and she hopes she’s pregnant by him.”

“Why would she have left, then?” Giula asked.

“That’s obvious,” Bella said. “She was an initiate, wasn’t she? Maybe the boy wasn’t.”

“Still,” I said. “Why would she leave Cuore?”

“Maybe . . .” Bella closed her eyes and rubbed her forehead. “This is getting too complicated. Even if the relationship ended badly, if she has any reason to think she’s pregnant, then coming back to Verdia would just be stupid.”

Celia tossed her hair back. “Clearly, you’ve never been in love.”

Bella’s eyes narrowed and she smiled slowly at Celia, letting Celia’s words hang in the air as a pink flush crept slowly upward from the gray wool collar of Celia’s robe. “If I risk being expelled from the conservatory,” Bella said, “I want it to be for a man, not a boy. But to each her own.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” Celia said.

Bella had started to turn back to her tea, but when Celia got defensive, she took that as an invitation to twist the knife a little more. “Why would it mean anything?” she asked. “I think your devotion to the Lady is very touching, Celia.”

Celia went white. Naturally, she attended chapel daily to flirt with the boys there, but Bella meant something else, and Celia knew it. Magery was the Lady’s gift to humanity, but it decreased fertility. To counteract this tendency, the Lady encouraged Her children to try to make children of their own as frequently as possible. Of course, the Lady didn’t want conservatory students having babies, our celibacy, like the sterility of the Circle, increased the fertility of everyone else. But, still. “Honoring the Lady” was a popular euphemism for the sort of thing that happened secretly on summer nights in the shadows of the practice halls, and that occasionally resulted in expulsions.

“The Lady rewards those who love Her with their whole heart,” Celia said, her voice shaky and her face still white. “You should try attending Chapel sometime when it isn’t required, Bella. The results might surprise you.”

“Sure, Celia,” Bella said, and returned to her tea. Celia stood up to go, and Bella caught her by the dangling edge of her sleeve. “Just be careful,” she said. “You know what I mean.” She released Celia, clucking her tongue, and Celia flounced out.

I tried to imagine Mira with a lover, and shook my head. Mira lacked the coy flirtatiousness it took to catch a boy’s eye. She was like me, a little bit intimidating. Besides, if she’d stopped using magery that long ago, why wouldn’t she have learned to light a candle by now?

Mira was not in the room when I returned from supper, but her cloak and violin were missing. She’d gone somewhere to practice, late though it was. She’d taken the candle. I slung my own violin over my shoulder and went out to see if I could find her. I was curious how well she could play, after all these years as a seminarian.

I listened carefully to the muffled cacophony in the corridor of the main practice hall. Two violins, but I recognized both. Not Giula, unfortunately, she needed the practice, but was probably studying for our music theory class.

I left through the back door, and as I crossed the courtyard, I saw the flicker of candlelight in the north practice hall. Many students used candles rather than witchlight while they practiced, but none of us used the north practice hall. It was cold, first of all, and so drafty that small drifts of snow actually blew across the floor in winter. And the acoustics were terrible. Bella once claimed it was haunted, though she was telling a ghost story to scare Giula and needed a creepy setting for it. In any case, the candle had to belong to Mira.

The front door of the north practice hall was ajar. I slipped in and paused in the shadow. Mira was playing in the ensemble hall rather than one of the side rooms; she had set her candle in a wall niche that protected it from drafts, but it still wavered, making her shadow dance on the wall. It occurred to me that sneaking around to spy on another student practicing was a little absurd, but I was curious about Mira. I put down my violin very quietly, sat with my cloak huddled around me, and listened.

Mira started off with very basic études, finger exercises. Her fingers were clumsy, and she missed many of the notes, which wasn’t surprising for someone who’d spent the last few years in a seminary rather than a conservatory. But as she warmed up and the fluidity began to come back to her, she began to make the études sound like something I hadn’t expected. She treated them as if they were music rather than a demonstration of technical skill; I realized, listening to her, that the world was slipping away around her, and nothing but each note existed. Her technique was raw, but the sound was beautiful. I wondered how she was able to bring herself to give this up, when she thought she had a calling, and if her calling was so powerful, how she had been able to give that up, now.

Then she finished with her exercises and began to play a melody, and I froze.

There were a few songs once used in old village ceremonies that still circulated at the conservatory. Playing ritual music from the Old Way was illegal, of course. And it would have been dangerous in a city conservatory, because of the Sudditi Fedeli della Signora, the Faithful Subjects of the Lady. But the Fedeli avoided backwater areas like Verdia, and most everyone shrugged off the danger. I certainly did. I knew a wedding song and a healing song, and I played them regularly. The Old Way music had an undercurrent that more recent music completely lacked. Most Old Way songs were in a minor key, but they were fast, with rhythms that felt like the heartbeat of the earth underneath me, and they stirred my blood like strong wine and cold wind.

I had never heard the song Mira was playing, but I recognized it as Old Way music from the peculiar rhythm: da dat da da dat da wham wham wham. Da dat da da dat da wham wham wham. Listening intently, I could see Mira throw her head back as she played, raising the violin like an offering, and I thought, she was studying to be a priestess?

Mira played the song through twice, picking up the tempo as she played. A cold draft touched my feet where I sat, and I curled my toes up inside my boots, clenching and flexing my hands. Then, midphrase, Mira stopped. She set her violin down carefully on the floor, and straightened for a moment, looking at the candle. Then she bent over and vomited on the floor, and vomited again, and then fell to her knees, still retching. I jumped to my feet. “Mira!”

She should have been startled by my presence, but she didn’t even look up. When I reached her, she was curled up on the cold stone floor, clenching her fists and wrapping her arms around herself. “I’ll get the physician,” I said.

“No,” she gasped, and grabbed the edge of my robe in her fist. “No, it won’t do any good. Stay here. Don’t leave me. This will pass. It will pass.”

I didn’t believe her, but I was afraid she might be dying, and she might die alone if I left her. So I dragged her away from her vomit on the floor, then covered her with her cloak and sat down beside her. She was shaking harder than I’d ever seen anyone shake from cold. After a moment I covered her with my own cloak, as well.

“I’ll be fine,” she said, between spasms of shaking. “Don’t worry about me.”

“Lady’s tits, Mira,” I said. “Let me get the physician. Or Giorgi, the cook’s assistant, he’s the village healer.”

“No,” she said. “I just want you. Stay with me. Please, don’t leave me.”

“But I don’t know anything about healing,” I said. I touched her forehead with the back of my hand to test for fever, but it was cool, even chill.

“I don’t need healing,” she said. “Talk to me.”

“What do you want me to talk about?” I asked.

“Anything,” she said. “Just let me hear your voice, so I know I’m not alone.”

So I talked. I told her about my family, about my favorite brother, the second-oldest, Donato, who taught me to fight and used to make me clay whistles. I told her about my friends at the conservatory, Giula and Bella and Flavia and Celia. I told her about the song that had arrived so mysteriously, about poisoned honey and dead children. I told her about my teacher, Domenico, how he was one of the handful of great teachers still left at the conservatory. Domenico had been educated at the Central Conservatory in Cuore and had actually spent several years playing at the Imperial Court before he gave it all up to come live in Verdia and teach at our conservatory. No one really knew why. Domenico told me he’d hated court, and from his descriptions of it I could understand why, though I still dreamed of playing there myself.

Mira shuddered, but this time she didn’t stop. Her eyes rolled back in her head, and she shook as if invisible hands grasped her shoulders and wrenched her back and forth. I had seen one other person have a convulsion, one of my nieces, when she was a baby and had a high fever. My mother had poured cold water over her and she’d lived. But Mira had no fever; her skin was as cold as the stones underneath us. I grabbed her and tried to hold her still, but her jerks pulled her out of my grasp. Then a moment later it was over, and she lay still. I held my hand lightly over her lips; she was still breathing. I sat back silently, clasping her limp hand. Mira’s hand was like carved marble, cold and impossibly smooth. I rubbed her palm with my thumb and suddenly my own blood turned cold. Mira had no calluses on her hands, not even the sort she’d have had from light garden work.

One of my brothers had trained for the priesthood for a while. He’d given it up after falling in love with a girl in the village, but I clearly remembered his complaints to our mother about the work. The elder priests and priestesses talked a lot about communing with the Lord and the Lady through reaping their bounty, but my brother thought that was just an excuse to stick the novitiates with all the heavy farm chores. I’d grown up on a farm and my brother was no stranger to hard work, but after a year at the seminary his calluses were thicker than my father’s.

I touched Mira’s soft hand again. She had never been an initiate priestess. That whole story was a lie.

Why would she make up a story like that?

I lit a globe of witchlight to get a closer look, and Mira threw her free hand over her face with a groan. “Hurts my eyes,” she muttered. “Put it away.”

I dispelled the witchlight with a flick of my wrist. Mira drew her hand away slowly.

“Play for me,” she said.

Her violin was in reach and in tune, while mine wasn’t, so I picked hers up.

“Play the funeral song,” she said. “The song I was playing earlier. I know you were listening.”

So it had been a funeral song. I added that mentally to my repertoire and began to play. I have always been able to pick out tunes quite easily, and I experimented a little as I played, adding a forceful downstroke to the strong beats and pairing them with the same note an octave up. Domenico had told me to hold still while I played, but Old Way songs always made me want to use my whole body, and I swayed back and forth with the music. I closed my eyes, watching the flicker of the candle against my eyelids. Then I opened my eyes.

For the first crazy instant, I thought a third person had silently entered the north practice hall, dressed in the uniform of a soldier. Then I thought I recognized my own face around the dark, riveting eyes. I started to my feet, and then realized that all I was looking at was a crumbling fresco. This was one of the oldest buildings at the conservatory, and had once been lavishly decorated.

I forced out a laugh. “I’ve been listening to too many of Bella’s ghost stories,” I said. Mira was silent. Slowly, I sat back down on the stone floor, more shaken than I thought I had any call to be. “The candlelight is making me jumpy.”

I set down Mira’s violin and took her soft hand again just as the candle went out.

I stayed beside her through the night, talking when she roused enough to ask to hear my voice. Mira seemed to waver from consciousness to unconsciousness like a sputtering flame, but when she woke she seemed glad to have me there. In the last part of the night, her tremors calmed, and I asked if she’d like me to help her back to the room, where she might be more comfortable. She sat up, still shaking a bit. “Thank you,” she said. “I’d appreciate that.”

I packed up her violin and slung both hers and mine over my shoulder, then wrapped her cloak around her shoulders and slipped my arm under hers. If anyone was out and about at that hour, they were on their own business and pretended not to see us; I helped Mira up the long staircase and into our empty room, then helped her sit down on the bed. Mira lay down and pulled her blanket over herself, closing her eyes. Her shaking had finally eased.

There was an hour or so before I’d have to get up, and I quietly slipped my boots off. As I hung Mira’s cloak up, something fluttered to the floor. I picked it up and kindled a tiny witchlight, hoping that it wouldn’t disturb Mira; it was a letter of some kind. You stupid fools, it said. We don’t want your money. We want our daughter back. I flipped it over; it was signed, Isabella and Marino of Tafano, Verdia. I slipped the letter under a musical score on her desk, ashamed of myself for reading it.

“What?” Mira said, and I jumped, flicking away my witchlight and nearly scattering the papers again. In the darkness, I lay down on my own bed, curling up under my blanket.

“I’m leaving,” Mira said, her voice as clear as the bells we rang at the Viaggio service.

“What?” I said, but Mira went on without heeding me, and I realized that she was talking in her sleep.

“You’re wrong, Liemo,” she said. Her voice was contemptuous. “I’ll break the chains you’ve bound me with. The Lady promises freedom and I’m going to take it. You can lock me up, you can even kill me, but you can’t make me serve you again.”

She was quiet after that, her breathing low and even. I lay awake, shivering. I told myself that I was still cold from the practice hall, but the fierce steel in Mira’s voice had cut me to the bone. I didn’t know whom she was speaking to, or what she was talking about, but I hoped I’d never find myself standing against her. In the end, I didn’t sleep at all that night. At dawn, Mira opened her eyes and looked over at me, giving me a slow smile that warmed me to my feet. “You will keep my secret?” she said.

I didn’t even know what her secret was, but looking into her eyes, I would have done anything for her. “Yes,” I said. “Yes.”

Descriere

From a gifted new voice in fantasy comes this saga of a war-ravaged land and the young woman destined to restore it. Sixteen-year-old Eliana studies at the Conservatory of Music hoping for an Imperial Court appointment. But in a land blighted by famine, and dominated by a fearsome religious order which brutally kills a student for clinging to forbidden ways, Eliana decides to escape and vows to spread the truth.

Notă biografică

Naomi Kritzergrew up in Madison, Wisconsin, a small lunar colony populated mostly by PhDs. She moved to Minnesota to attend college. After graduating with a BA in religion, she became a technical writer. Kritzer now lives in Minneapolis with her family.Fires of the Faithfulwas her first novel, followed shortly thereafter byTurning the Storm, Freedom's Gate,andFreedom's Apprentice.