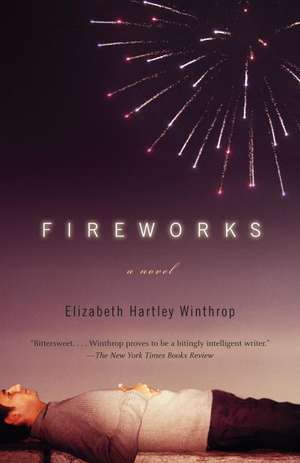

Fireworks

Autor Elizabeth Hartley Winthropen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2007

Preț: 76.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 114

Preț estimativ în valută:

14.62€ • 15.06$ • 12.24£

14.62€ • 15.06$ • 12.24£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096978

ISBN-10: 1400096979

Pagini: 289

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

ISBN-10: 1400096979

Pagini: 289

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.24 kg

Editura: Vintage Books USA

Notă biografică

Elizabeth Hartley Winthrop was born and raised in New York City. She graduated Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude from Harvard University in 2001. In 2004 she received her MFA in fiction from the University of California at Irvine, and she was the recipient of the Schaeffer Writing Fellowship for the 2004-5 academic year. She lives in Savannah, Georgia.

Extras

1 FIREWORKS

When my grandfather died, I told everyone he’d been killed by aborigines while he was berry-picking in Africa. I told them that I had been there, too. I told this to my friends, and to their parents. I told this to the lifeguard at our neighborhood pool. I told this to the gas station attendants and motel clerks my father and I met on our drive down to Florida for the funeral. I wrote about it in a letter to my mother, who had left us that spring to live in a commune upstate. I was picturing dry, open fields, the occasional crooked tree under which a lion might have lounged or beside which a giraffe might have stood with his neck stretched to reach the topmost leaves. I was picturing jeepfuls of tribal rivals speeding around with shotguns, like what I’d seen in The Gods Must Be Crazy, my poor grandfather in the line of fire, myself lying flat in hiding behind a log.

This was during my safari phase. My wife found a picture of me from around this time up in the attic just the other day. She brought it downstairs to show it to me. I was sitting on the porch with a Jack Daniel’s, enjoying the sunset. “You were adorable,” she said. In the picture, I’m wearing khaki trousers that unzip into shorts around the thigh. I’ve got a khaki vest on, and a safari hat. There’s a stuffed monkey pinned to the back of my pants, and a plastic snake hung around my neck. I’m carrying a small pair of binoculars, and there’s chocolate on my face. I got a little chill when my wife showed me the picture, even though it was June. “Mmm,” I said. “I’m not so cute.”

My name is Hollis. I’m a writer, and I live with my wife in a midsize, coastal New England town. My wife is a teacher. We have no children. We did, but our son, Simon, was killed nearly two years ago by a bunch of kids in a speeding car.

I’ve been cheating on my wife. My girlfriend, Marissa, is twenty-four, almost fifteen years younger than I am. I met her ten months ago at a bus stop when I was on my way to a meeting with my editor. It was raining, neither of us had an umbrella, and the buses were running late, so instead of waiting we shared a cab, which we quickly redirected from our respective destinations to her apartment. We’ve spent hours there together every afternoon since then. Some might consider me lucky. But oftentimes, as I’m drifting in and out of sleep in the late afternoon light, I feel lonely. I feel like I’m being rolled around in a huge wave of loneliness. When Marissa asks me what’s wrong, I don’t say anything about it, because who am I to be lonely? I have Marissa, I have my wife, and I know they both love me. I am never alone.

I went through phases as a kid. I was a fireman for a while. My uncle really was a fireman, so I had the real stuff from him: helmet, gloves, charred bricks from burned-down buildings. I was Robin Hood. I wore the tights only on Halloween, but I carried a bow and arrows around for months. For a while I was a break-dancer. I wore a bandanna and a single black leather glove with the fingers cut off.

“A safari phase,” my wife said when she showed me the picture. “I don’t think I knew about that one.”

“It was brief.” I shifted in my chair so I could better see the sunset. I sipped my Jack Daniel’s.

My wife stood behind me and ran her fingers through my hair.

Marissa is standing in my wife’s kitchen. That’s how I think of it when I see Marissa bending to open the cabinets that my wife bends to open, or leaning against the countertops my wife leans against. I watch her in my wife’s apron, using my wife’s utensils to make us dinner before the fireworks start downtown. She looks up and sees me staring.

“What?” she says.

I shake my head. My wife has gone to spend the Fourth of July with her old college roommate, and so the house is mine alone. This is only the second time Marissa has been here. She seems unbothered by it.

“Is this you?” she asks. My wife has hung the photograph of me in my safari gear on the refrigerator. I nod.

“On my way to Florida, for my grandfather’s funeral,” I say. “Do you believe I wore that to the actual funeral?”

Marissa smiles and shakes her head. She takes the photograph from the refrigerator door and holds it between the tips of her fingers, just like my wife did.

When my grandfather died, he died suddenly, of a massive stroke. My father decided to drive down to Florida for the funeral, and since he had no one to leave me with, he brought me with him, even though I’d never even met my grandparents.

What I remember most about the drive are the bugs. The farther south we drove, the thicker the clouds of them became, these humming throngs of insects that hovered over the highway and smacked against the windshield as our car plowed through them. And I remember once waking up at a gas station to a sound I couldn’t immediately identify. I was in the front seat of the car, alone. Out the side window I could see gas pumps, air pumps, diesel tanks, oil cans. I’d unzipped my safari pants into shorts, and my skin was stuck to the leather of the seat. Ridges of upholstery had set patterns into the backs of my thighs.

The windshield was near opaque with the blood and smear of bugs, and I soon realized that the scratching sound was the sound of a knife against the windshield’s glass. As the glass cleared, I could watch my father as he scratched at the glass. His forearms were ridged with muscle, and hairy, and in his hand the knife he used to clear the windshield looked small. I shifted my weight from one side to the other, peeling my skin from where it seemed to have melted into the seat.

“Stroke,” I say when Marissa asks me how my grandfather died. “I didn’t know him.” I shrug. “His wake was the first time I’d ever seen him,” I say.

It was the first time I’d met my grandmother, too. When my father and I pulled in to her driveway, it was dusk. We went through the kitchen door and found her sitting at the kitchen table with a rocks glass filled with vodka and milk on ice. There was a slant of evening light coming through the small window above the sink and falling on her hands. I remember staring at the way the light made the webs of skin between her knuckles glow translucent, and I remember the way it glinted in her rings. She wore four rings on one finger, a column of ruby, diamond, emerald, sapphire.

She looked up as we walked through the door. “Mom,” my father said.

She lifted her glass to her lips and took a sip. “Who are you?” she said.

I watch Marissa, on tiptoe reaching for a bottle of wine from the rack above the fridge. She is small. Her fingers just reach the nose of a bottle when she really stretches, and she’s trying to coax it out one reach at a time so that maybe she can get a good grip on it. I go up behind her and take the bottle down, and she turns so that we are facing each other, very close, her face against my chest. I pause, not because I don’t like the feel of Marissa against me, but because this posture was not what I intended. I helped her with the wine so that the bottle wouldn’t fall and break, not so that we could be close. Her breath is hot against my chest and she runs her hands down my sides.

It is moments like these that make me feel lonely.

She looks up at me. “What?” she says.

I shake my head and bend to kiss her hair. “Nothing,” I say.

“Where would I find a wine opener?” she says.

“Drawer to the left of the sink,” I say. She plants a kiss on my chest and steps out from between me and the refrigerator, leaving me face-to-face with myself, safari style.

We were in Florida for ten days. The heat was unlike anything I’d experienced before. My cousins hung off the dock at the lake below my grandparents’ house, but I’d seen snakes in that water, so I opted not to join them. I told anyone who asked that I simply was not hot. It would have been a betrayal of my safari persona to admit that snakes could scare me.

I also stayed away from the house, where my aunts helped my grandmother rummage through my grandfather’s old things, and where uncles muttered around the kitchen table about what should become of the house, of the property, of my grandmother. My cousin Toby, who was four or five years older than I was and who lived with his mother, my father’s only sister, across the street from my grandparents, told me that they wanted to lock my grandmother up, her three sons. He said they thought she was crazy and a drunk. “She’s not,” he said, slapping a mosquito from his leg with a towel. “I think I would know better than them. I live here, unlike you dumb Yankees.” He flung his towel around his neck and ran down to the lake, and I watched him as he cannonballed himself into the water, snakes and all.

I spent a good amount of time in the old storage shed, spinning the wheel of an overturned bicycle and listening to the hum of the spokes when it got going fast.

I spent a good amount of time at work on the tree behind the shed, peeling away the bark and carving words and pictures in the smooth wood beneath.

Then there was my grandmother’s car. It was an old car with fins, and it was shiny blue. The seats were green leather and so wide that I could stretch myself out fully on them. My grandmother was in the habit of taking a drive early each morning, maybe because it was the only time she was sober enough to do so, and I guess so she wouldn’t lose them she always left the keys in the car. I’d turn them in the ignition partway and listen to the radio for hours at a time. Sometimes, I would lie down and stare at the material drooping from the ceiling as I listened, or up through the window at the sky and trees, all upside down from my angle. Other times, I sat in the backseat and pretended I had a chauffeur. Best, though, was taking the wheel myself and driving through the African brush, dodging killer rhinos and tigers. Best was speeding across the desert plains, kicking up plumes of dust that would hover, then settle and cover my tracks so that the aborigines hunting me down wouldn’t know which way I’d gone. Best was hunting for lion and zebra with my loyal dog eagerly peering over my shoulder and sniffing the air as we drove.

My loyal dog was Max, my grandmother’s bloodhound. Max was a big, silly dog. His skin had settled in loose rings around his neck, and his jowls drooped an inch below his mouth. His lips slung spit when he turned his head. His ears were like velvet. I liked Max okay. Whenever I drank from my bottle of water, I poured some into my hands for him to drink, too, despite his refusal to play the role of safari hunting dog. He didn’t sniff the air or peer over my shoulder when I piled him into the car; he lay drooling in the backseat, his paws hanging over the seat’s edge and his eyebrows twitching with dreams. Sometimes I forgot he was even there.

From the Hardcover edition.

When my grandfather died, I told everyone he’d been killed by aborigines while he was berry-picking in Africa. I told them that I had been there, too. I told this to my friends, and to their parents. I told this to the lifeguard at our neighborhood pool. I told this to the gas station attendants and motel clerks my father and I met on our drive down to Florida for the funeral. I wrote about it in a letter to my mother, who had left us that spring to live in a commune upstate. I was picturing dry, open fields, the occasional crooked tree under which a lion might have lounged or beside which a giraffe might have stood with his neck stretched to reach the topmost leaves. I was picturing jeepfuls of tribal rivals speeding around with shotguns, like what I’d seen in The Gods Must Be Crazy, my poor grandfather in the line of fire, myself lying flat in hiding behind a log.

This was during my safari phase. My wife found a picture of me from around this time up in the attic just the other day. She brought it downstairs to show it to me. I was sitting on the porch with a Jack Daniel’s, enjoying the sunset. “You were adorable,” she said. In the picture, I’m wearing khaki trousers that unzip into shorts around the thigh. I’ve got a khaki vest on, and a safari hat. There’s a stuffed monkey pinned to the back of my pants, and a plastic snake hung around my neck. I’m carrying a small pair of binoculars, and there’s chocolate on my face. I got a little chill when my wife showed me the picture, even though it was June. “Mmm,” I said. “I’m not so cute.”

My name is Hollis. I’m a writer, and I live with my wife in a midsize, coastal New England town. My wife is a teacher. We have no children. We did, but our son, Simon, was killed nearly two years ago by a bunch of kids in a speeding car.

I’ve been cheating on my wife. My girlfriend, Marissa, is twenty-four, almost fifteen years younger than I am. I met her ten months ago at a bus stop when I was on my way to a meeting with my editor. It was raining, neither of us had an umbrella, and the buses were running late, so instead of waiting we shared a cab, which we quickly redirected from our respective destinations to her apartment. We’ve spent hours there together every afternoon since then. Some might consider me lucky. But oftentimes, as I’m drifting in and out of sleep in the late afternoon light, I feel lonely. I feel like I’m being rolled around in a huge wave of loneliness. When Marissa asks me what’s wrong, I don’t say anything about it, because who am I to be lonely? I have Marissa, I have my wife, and I know they both love me. I am never alone.

I went through phases as a kid. I was a fireman for a while. My uncle really was a fireman, so I had the real stuff from him: helmet, gloves, charred bricks from burned-down buildings. I was Robin Hood. I wore the tights only on Halloween, but I carried a bow and arrows around for months. For a while I was a break-dancer. I wore a bandanna and a single black leather glove with the fingers cut off.

“A safari phase,” my wife said when she showed me the picture. “I don’t think I knew about that one.”

“It was brief.” I shifted in my chair so I could better see the sunset. I sipped my Jack Daniel’s.

My wife stood behind me and ran her fingers through my hair.

Marissa is standing in my wife’s kitchen. That’s how I think of it when I see Marissa bending to open the cabinets that my wife bends to open, or leaning against the countertops my wife leans against. I watch her in my wife’s apron, using my wife’s utensils to make us dinner before the fireworks start downtown. She looks up and sees me staring.

“What?” she says.

I shake my head. My wife has gone to spend the Fourth of July with her old college roommate, and so the house is mine alone. This is only the second time Marissa has been here. She seems unbothered by it.

“Is this you?” she asks. My wife has hung the photograph of me in my safari gear on the refrigerator. I nod.

“On my way to Florida, for my grandfather’s funeral,” I say. “Do you believe I wore that to the actual funeral?”

Marissa smiles and shakes her head. She takes the photograph from the refrigerator door and holds it between the tips of her fingers, just like my wife did.

When my grandfather died, he died suddenly, of a massive stroke. My father decided to drive down to Florida for the funeral, and since he had no one to leave me with, he brought me with him, even though I’d never even met my grandparents.

What I remember most about the drive are the bugs. The farther south we drove, the thicker the clouds of them became, these humming throngs of insects that hovered over the highway and smacked against the windshield as our car plowed through them. And I remember once waking up at a gas station to a sound I couldn’t immediately identify. I was in the front seat of the car, alone. Out the side window I could see gas pumps, air pumps, diesel tanks, oil cans. I’d unzipped my safari pants into shorts, and my skin was stuck to the leather of the seat. Ridges of upholstery had set patterns into the backs of my thighs.

The windshield was near opaque with the blood and smear of bugs, and I soon realized that the scratching sound was the sound of a knife against the windshield’s glass. As the glass cleared, I could watch my father as he scratched at the glass. His forearms were ridged with muscle, and hairy, and in his hand the knife he used to clear the windshield looked small. I shifted my weight from one side to the other, peeling my skin from where it seemed to have melted into the seat.

“Stroke,” I say when Marissa asks me how my grandfather died. “I didn’t know him.” I shrug. “His wake was the first time I’d ever seen him,” I say.

It was the first time I’d met my grandmother, too. When my father and I pulled in to her driveway, it was dusk. We went through the kitchen door and found her sitting at the kitchen table with a rocks glass filled with vodka and milk on ice. There was a slant of evening light coming through the small window above the sink and falling on her hands. I remember staring at the way the light made the webs of skin between her knuckles glow translucent, and I remember the way it glinted in her rings. She wore four rings on one finger, a column of ruby, diamond, emerald, sapphire.

She looked up as we walked through the door. “Mom,” my father said.

She lifted her glass to her lips and took a sip. “Who are you?” she said.

I watch Marissa, on tiptoe reaching for a bottle of wine from the rack above the fridge. She is small. Her fingers just reach the nose of a bottle when she really stretches, and she’s trying to coax it out one reach at a time so that maybe she can get a good grip on it. I go up behind her and take the bottle down, and she turns so that we are facing each other, very close, her face against my chest. I pause, not because I don’t like the feel of Marissa against me, but because this posture was not what I intended. I helped her with the wine so that the bottle wouldn’t fall and break, not so that we could be close. Her breath is hot against my chest and she runs her hands down my sides.

It is moments like these that make me feel lonely.

She looks up at me. “What?” she says.

I shake my head and bend to kiss her hair. “Nothing,” I say.

“Where would I find a wine opener?” she says.

“Drawer to the left of the sink,” I say. She plants a kiss on my chest and steps out from between me and the refrigerator, leaving me face-to-face with myself, safari style.

We were in Florida for ten days. The heat was unlike anything I’d experienced before. My cousins hung off the dock at the lake below my grandparents’ house, but I’d seen snakes in that water, so I opted not to join them. I told anyone who asked that I simply was not hot. It would have been a betrayal of my safari persona to admit that snakes could scare me.

I also stayed away from the house, where my aunts helped my grandmother rummage through my grandfather’s old things, and where uncles muttered around the kitchen table about what should become of the house, of the property, of my grandmother. My cousin Toby, who was four or five years older than I was and who lived with his mother, my father’s only sister, across the street from my grandparents, told me that they wanted to lock my grandmother up, her three sons. He said they thought she was crazy and a drunk. “She’s not,” he said, slapping a mosquito from his leg with a towel. “I think I would know better than them. I live here, unlike you dumb Yankees.” He flung his towel around his neck and ran down to the lake, and I watched him as he cannonballed himself into the water, snakes and all.

I spent a good amount of time in the old storage shed, spinning the wheel of an overturned bicycle and listening to the hum of the spokes when it got going fast.

I spent a good amount of time at work on the tree behind the shed, peeling away the bark and carving words and pictures in the smooth wood beneath.

Then there was my grandmother’s car. It was an old car with fins, and it was shiny blue. The seats were green leather and so wide that I could stretch myself out fully on them. My grandmother was in the habit of taking a drive early each morning, maybe because it was the only time she was sober enough to do so, and I guess so she wouldn’t lose them she always left the keys in the car. I’d turn them in the ignition partway and listen to the radio for hours at a time. Sometimes, I would lie down and stare at the material drooping from the ceiling as I listened, or up through the window at the sky and trees, all upside down from my angle. Other times, I sat in the backseat and pretended I had a chauffeur. Best, though, was taking the wheel myself and driving through the African brush, dodging killer rhinos and tigers. Best was speeding across the desert plains, kicking up plumes of dust that would hover, then settle and cover my tracks so that the aborigines hunting me down wouldn’t know which way I’d gone. Best was hunting for lion and zebra with my loyal dog eagerly peering over my shoulder and sniffing the air as we drove.

My loyal dog was Max, my grandmother’s bloodhound. Max was a big, silly dog. His skin had settled in loose rings around his neck, and his jowls drooped an inch below his mouth. His lips slung spit when he turned his head. His ears were like velvet. I liked Max okay. Whenever I drank from my bottle of water, I poured some into my hands for him to drink, too, despite his refusal to play the role of safari hunting dog. He didn’t sniff the air or peer over my shoulder when I piled him into the car; he lay drooling in the backseat, his paws hanging over the seat’s edge and his eyebrows twitching with dreams. Sometimes I forgot he was even there.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

"Bittersweet. . . . Winthrop proves to be a bitingly intelligent writer." —The New York Times Book Review"Reads like a heartfelt collision of Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King and the Oscar-winning American Beauty. . . . Pitch-perfect first-person narration." —Pages“Wry . . . Winthrop portrays with poignant humor the characters and events in Hollis' anxiety-filled existence." —Chicago Tribune"Brimming with gentle wisdom." —Redbook

Descriere

In an eviscerating comic portrait of suburban despair, Winthrops debut novel captures the mysterious seasons of a mans inner and outer life--marriage, grief, existential confusion, and finally, love--and the human spirits insistent and sometimes incongruous motion toward grace.