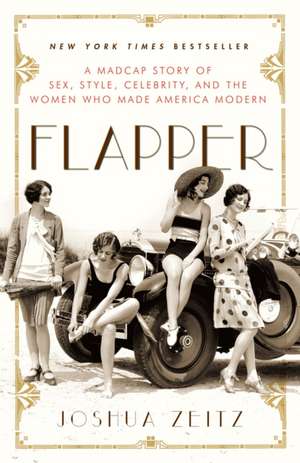

Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern

Autor Joshua Zeitzen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 ian 2007

Whisking us from the Alabama country club where Zelda Sayre first caught the eye of F. Scott Fitzgerald to Muncie, Indiana, where would-be flappers begged their mothers for silk stockings, to the Manhattan speakeasies where patrons partied till daybreak, historian Joshua Zeitz brings the era to exhilarating life. This is the story of America’s first sexual revolution, its first merchants of cool, its first celebrities, and its most sparkling advertisement for the right to pursue happiness.

The men and women who made the flapper were a diverse lot.

There was Coco Chanel, the French orphan who redefined the feminine form and silhouette, helping to free women from the torturous corsets and crinolines that had served as tools of social control.

Three thousand miles away, Lois Long, the daughter of a Connecticut clergyman, christened herself “Lipstick” and gave New Yorker readers a thrilling entrée into Manhattan’s extravagant Jazz Age nightlife.

In California, where orange groves gave way to studio lots and fairytale mansions, three of America’s first celebrities—Clara Bow, Colleen Moore, and Louise Brooks, Hollywood’s great flapper triumvirate—fired the imaginations of millions of filmgoers.

Dallas-born fashion artist Gordon Conway and Utah-born cartoonist John Held crafted magazine covers that captured the electricity of the social revolution sweeping the United States.

Bruce Barton and Edward Bernays, pioneers of advertising and public relations, taught big business how to harness the dreams and anxieties of a newly industrial America—and a nation of consumers was born.

Towering above all were Zelda and Scott Fitzgerald, whose swift ascent and spectacular fall embodied the glamour and excess of the era that would come to an abrupt end on Black Tuesday, when the stock market collapsed and rendered the age of abundance and frivolity instantly obsolete.

With its heady cocktail of storytelling and big ideas, Flapper is a dazzling look at the women who launched the first truly modern decade.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 132.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 199

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.35€ • 26.47$ • 20.98£

25.35€ • 26.47$ • 20.98£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400080540

ISBN-10: 1400080541

Pagini: 338

Ilustrații: 27 B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 1400080541

Pagini: 338

Ilustrații: 27 B&W PHOTOS THROUGHOUT

Dimensiuni: 132 x 203 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.35 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Joshua Zeitz is a lecturer on American history and fellow of Pembroke College at the University of Cambridge and is a contributing editor at American Heritage. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, New Republic, and Forward. He lives in New York and Cambridge, England. Visit his website at FlapperBook.com.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

1

The Most Popular Girl

For all intents and purposes, and purely by virtue of chance, America’s Jazz Age began in July 1918 on a warm and sultry evening in Montgomery, Alabama. There, at the Montgomery Country Club—“a rambling brown-shingled building,” as one contemporary later remembered it, “discreetly screened from the public eye by an impenetrable hedge of mock oranges”—a strikingly beautiful woman named Zelda Sayre sauntered onto the clubhouse veranda and caught the eye of First Lieutenant Francis Scott Fitzgerald.

At seventeen, Zelda was “sophisticated for her age,” recalled one of her friends, but “she still had the charm of an uninhibited, imaginative child.”

As she stood outside the clubhouse amid the dull murmur of the brass dance music emanating from within, bathed by the Alabama moonlight, her “summer tan gave her skin the color of a rose petal dripped in cream. Her hair had the sheen of spun gold. Wide and dark-lashed, her eyes seemed to change color with her prismatic moods; though in reality they were deep blue, at times they appeared to be green or even a dark Confederate gray.” Just one month out of high school, Zelda was “slender and well-proportioned,” “lithe,” and “extraordinarily graceful.”

Among the younger set, Zelda Sayre was commonly acknowledged as something of a wild child. She particularly delighted in scandalizing her father, Judge Anthony Sayre, a staid Victorian who, in his capacity as an associate justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, was one of Montgomery’s leading citizens.

Given her family’s standing in the community, Zelda’s frequent exploits were sure fodder for gossip. There was the day she climbed to the roof of her house, kicked away the ladder, and compelled the fire company to rescue her from certain injury and disgrace. Or the time she borrowed her friend’s snappy little Stutz Bearcat to drive down to Boodler’s Bend, a local lover’s lane concealed by a thick orchard of pecan trees, and shone a spotlight on those of her schoolmates who were necking in the backseats of parked cars. Or those other occasions when she repeated the same trick, but at the front entrance to Madam Helen St. Clair’s notorious city brothel.

Most disturbing to Judge Sayre was Zelda’s well-earned reputation for violating the time-honored codes of sexual propriety that seemed everywhere under attack by the time the opening shots were fired in World War I. Already a veritable legend among hundreds of well-heeled fraternity brothers as far and wide as the University of Alabama, Auburn University, and Georgia Tech, Zelda was “the most popular girl at every dance,” as a would-be suitor remembered years later.

Part of Zelda’s renown surely was owed to her habit of sneaking out of country club dances—and sometimes her bedroom window—to join Montgomery’s most eligible bachelors for a few hours of necking, petting, and drinking in secluded backseat venues. On more than a few occasions, the inviting aroma of pear trees, the dim glow of a half-moon, and the tentative sound of a boyfriend’s car horn were all the inspiration Zelda needed to walk quietly across her plain whitewashed room, draw open the curtains, and creep down to the tin roof that protected the Sayre family’s front porch.

After that, she was gone into the night.

During her four years at Sidney Lanier High School, Zelda was an average student, but she was well ahead of the learning curve in most other matters. She habitually rouged her cheeks and stenciled her eyes with mascara, giving her friends’ parents great cause for concern.

A regular at the local soda fountain, she alternated between double banana splits (innocuous) and a “dopes” (not so innocuous), a combination of Coca-Cola and aromatic spirits.

When the entire senior class cut school on April 1, it was Zelda who pooled everyone’s money and flirted with the nice agent at the Empire Theatre, who happily granted the students admission at a cut rate. And it was Zelda who triumphantly organized a group photo in front of the ticket box.

When her English teacher assigned a poetry-writing exercise for homework, Zelda immediately volunteered to read her original

composition—scratched out the next morning in homeroom—aloud.

I do love my Charlie so.

It nearly drives me wild.

I’m so glad that he’s my beau

And I’m his baby child!

It was a big hit with her classmates, but not exactly what the teacher was looking for.

For all of Zelda’s purported daring, Sara Mayfield, her loyal childhood friend, averred that she was no better or worse than most young women of her time. “Zelda would have been the last to deny that she danced cheek to cheek and did the Shimmy, the Charleston, and the Black Bottom,” Mayfield admitted. But “if she gave a demonstration of the Hula at a midterm dance at the University of Alabama, had not Alice Roosevelt, the President’s daughter, been similarly criticized for doing the same thing . . . ?”

To be sure, Zelda “rode behind her admirers . . . on their motorcycles with her arms around them, raised her hemlines to the knee, bobbed her hair, smoked, tippled, and kissed the boys goodbye.” But this sort of “flirtation was an old Southern custom; ‘going the limit’ was not. Zelda was a reigning beauty and ‘a knockout’ in the paleolithic slang of the day, far too popular to have ‘put out’ for her beaux, far too shrewd in the tactics and strategy of popularity to grant her favors to one suitor and thereby alienate a regiment of them.”

Maybe so, maybe not. But Zelda did her best to cultivate a scandalous reputation. She encouraged reports of skinny-dipping excursions and multiple romantic entanglements. During the summer, when it got too hot, she slipped out of her underwear and asked her date to hold it for the evening in his coat pocket. And at a legendary Christmas bop, when a chaperone reproached her for dancing too closely and too wantonly with her date, Zelda retaliated by swiping a band of mistletoe and pinning it to her backside.

Long after the last chords of the Jazz Age had been struck, Zelda admitted in her own autobiographical novel that “I never let them down on the dramatic possibilities of a scene—I give a damned good show.”

Scott Fitzgerald certainly thought so.

Just shy of his twenty-first birthday, the young army lieutenant was stationed at nearby Camp Sheridan, where he spent most of his time devouring novels and cavorting with the sons and daughters of Montgomery’s first citizens. Smartly clad in a new dress uniform, Fitzgerald cut an impressive figure. Shortly after the war, when Scott’s first book became a best-seller, an interviewer described him as bearing “the agreeable countenance of a young person who cheerfully regards himself as the center of everything.” His eyes were “blue and domineering,” his nose “Grecian and pleasantly snippy; mouth, ‘spoiled and alluring,’ like one of his own yellow-haired heroines; and he parts his wavy fair hair in the middle, as Amory Blaine”—the fictional hero of Fitzgerald’s first novel—“decided that all ‘slickers’ should do.”

Fitzgerald was a native of St. Paul, Minnesota, who had spent four years at Princeton without earning his undergraduate degree. An indifferent student, he received poor marks from his professors and made little contribution to classroom discussion. To his credit, Fitzgerald was an accomplished amateur playwright and a frequent contributor to the university literary magazine. But on balance, his academic career fell far short of even his expectations.

Lazy in all things but reading and writing, vaguely ambitious but hopelessly lacking direction, Fitzgerald escaped the indignity of a fifth year at Princeton by enlisting in the army in late 1917. First stationed at Fort Leavenworth for officer’s training, he made a poor impression on his platoon captain, a serious young West Point man named Dwight D. Eisenhower. Scott’s attention simply wasn’t on soldiering, and it showed. He fully expected that he would be sent to the European front, and fearing that he might return in a pine box, he accelerated work on his first novel, The Romantic Egotist. It consumed much of his time and all of his energy.

On short leave from the army in early 1918, Scott enjoyed a brief hiatus in Princeton, where he managed to finish the novel and send it off to an editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons. After reporting back for duty in March, he was transferred to the Forty-fifth Infantry Regiment at Camp Alexander in Kentucky. Though he was trained to lead a platoon, his commanding officers found Scott so deficient as a soldier that they consigned him to stateside duty—first at Camp Gordon in Georgia and then, in June 1918, at Camp Sheridan.

With his novel under review and combat service safely at bay, Fitzgerald was free to immerse himself in local revelries. Almost from the start, he began working his way through a list of Montgomery’s most eligible debutantes, generously supplied by Lawton Campbell, a local boy he had known at Princeton. In a more candid moment years later, Fitzgerald admitted that he had been naturally endowed with neither “great animal magnetism nor money,” two certain keys to success among the well-bred collegiate circles in which he moved back in the early days. Still, he knew that he had “good looks and intelligence,” qualities that generally helped him get the “top girl” wherever he went.

Lawton Campbell was several years older than Zelda Sayre and had left Montgomery before she entered high school; consequently, he didn’t include her on Scott’s roster of southern belles. It was purely by chance that she and Scott Fitzgerald happened upon each other that evening in July.

The moment his eyes locked on her, Scott was taken by Zelda’s beauty. Had he asked around, he would have learned of her dangerous reputation. As one contemporary remembered, “There were two kinds of girls, those who would ride with you in your automobile at night and the nice girls who wouldn’t. But Zelda didn’t seem to give a damn.”

At the first opportunity, Scott elbowed his way to her side and, finding that her dance card was full for the evening, asked if he might take her out after the country club festivities wound down. The faux East Coast drawl that he studiously cultivated at Princeton just barely concealed his flat Minnesota burr.

“I never make late dates with fast workers,” she replied sharply in the most properly southern of southern accents.

Nevertheless, she gave Scott her telephone number and subtly encouraged him to ply his charms another time.

Scott called Zelda at home the next day—and the next day after that, and again every day for the better part of two weeks until she relented. Not that it took a great deal of convincing. Scott was “a blond Adonis in a Brooks Brothers uniform,” one of their contemporaries remarked. He was, by Lawton Campbell’s estimation, “the handsomest boy I’d ever seen. He had yellow hair and lavender eyes” and a confident swagger that won over even his deepest skeptics.

In her autobiographical novel, Zelda evoked the sensation of dancing with Scott on one of their first dates. “[H]e smelled like new goods,” she wrote all those years later. “Being close to him, [my] face in the space between his ear and his stiff army collar was like being initiated into the subterranean reserves of a fine fabric store exuding the delicacy of cambrics and linen and luxury bound in bales.” Zelda was jealous of Scott’s “pale aloofness,” and when she watched him stroll arm in arm off the dance floor with other women, she felt a dull pang of resentment that he was “leading others than [me] into those cooler regions which he inhabited alone.”

To be fair, Zelda saw to it that Scott did most of the chasing. As one of Montgomery’s most popular debutantes, she already enjoyed scores of romantic opportunities from the usual college and business crowds. In normal times, Scott would have faced stiff competition from the likes of Dan Cody, the dashing young scion of a prominent Montgomery banking family, or Lloyd Hooper, an even wealthier son of an even wealthier Alabama line. Now, with America fully mobilized for war and thousands of doughboys in starched uniforms flooding Camp Sheridan, Zelda found herself one of the mostly hotly pursued belles in the state. Army aviators stationed at Camp Taylor honored her with elaborate aerial stunts and flyovers above the Sayre household, until an unfortunate pilot crashed his plane and died in a futile attempt to win Zelda’s affections. Army regulars staged a ceremonial drill on Pleasant Avenue in Zelda’s honor. Sara Mayfield claimed that when the war ended and all of Montgomery celebrated with a grand parade, “the military police had to break up the stag lines that crowded around her.”

By her own admission, Zelda’s attention wasn’t on school that year. There were too many “soldiers in town [and] I passed my time going to dances—always in love with somebody, dancing all night, and carrying on my school work just with [the] idea of finishing it.”

This fierce competition notwithstanding, within weeks of their first meeting Scott and Zelda fell deeply in love. Each weekend, Scott would hop the rickety old army bus at Camp Sheridan and ride it into downtown Montgomery; from there, he would take a short cab ride to 6 Pleasant Avenue and call on Zelda. They passed their days rocking quietly on the Sayres’ front porch swing and sipping cool drinks made of crushed ice and fruit. At night they danced away the hours at the country club, where Scott carved their initials in the front doorpost. Sometimes they strolled arm in arm around the pine groves that encircled the town. Scott joked that by the logic of both Keats and Browning, Zelda was destined to marry him. Good-naturedly, Zelda replied that Scott was an “educational feature; an overture to romance which no young lady should be without.”

That long Indian summer of 1918 would loom large in both their memories. Writing from her confinement in a mental hospital almost twenty years later, Zelda found that “at this dusty time of the year the flowers and trees take on the aspect of flowers and trees drifted from other summers.” The peculiar scent of pine needles evoked memories of “roads that cradled the happier suns of a long time ago.” She fondly bade Scott to recall the “night you gave me a birthday party and you were a young lieutenant and I was a fragrant phantom . . . it was a radiant night, a night of soft conspiracy and the trees agreed that it was all going to be for the best. . . . That’s the first time I ever said that in my life.”

Zelda’s eighteenth birthday fell on July 24, 1918, less than a month after they first met. If she and Scott didn’t consummate their relationship then, it’s almost certain they did so before the summer’s close. From an early age, Fitzgerald kept detailed scrapbooks that chronicled his life and his works in progress. An entry from 1935, containing notes for a short-story collection, reads: “After yielding she holds Philippe at bay like Zelda + me in summer 1917.” It was a slip of memory; he meant 1918. But this lone fragment, and Zelda’s later reminiscences, suggest that they slept together sometime before that November, when Scott left for Camp Mills, in New York, to await embarkation for Europe.

From the Hardcover edition.

1

The Most Popular Girl

For all intents and purposes, and purely by virtue of chance, America’s Jazz Age began in July 1918 on a warm and sultry evening in Montgomery, Alabama. There, at the Montgomery Country Club—“a rambling brown-shingled building,” as one contemporary later remembered it, “discreetly screened from the public eye by an impenetrable hedge of mock oranges”—a strikingly beautiful woman named Zelda Sayre sauntered onto the clubhouse veranda and caught the eye of First Lieutenant Francis Scott Fitzgerald.

At seventeen, Zelda was “sophisticated for her age,” recalled one of her friends, but “she still had the charm of an uninhibited, imaginative child.”

As she stood outside the clubhouse amid the dull murmur of the brass dance music emanating from within, bathed by the Alabama moonlight, her “summer tan gave her skin the color of a rose petal dripped in cream. Her hair had the sheen of spun gold. Wide and dark-lashed, her eyes seemed to change color with her prismatic moods; though in reality they were deep blue, at times they appeared to be green or even a dark Confederate gray.” Just one month out of high school, Zelda was “slender and well-proportioned,” “lithe,” and “extraordinarily graceful.”

Among the younger set, Zelda Sayre was commonly acknowledged as something of a wild child. She particularly delighted in scandalizing her father, Judge Anthony Sayre, a staid Victorian who, in his capacity as an associate justice of the Alabama Supreme Court, was one of Montgomery’s leading citizens.

Given her family’s standing in the community, Zelda’s frequent exploits were sure fodder for gossip. There was the day she climbed to the roof of her house, kicked away the ladder, and compelled the fire company to rescue her from certain injury and disgrace. Or the time she borrowed her friend’s snappy little Stutz Bearcat to drive down to Boodler’s Bend, a local lover’s lane concealed by a thick orchard of pecan trees, and shone a spotlight on those of her schoolmates who were necking in the backseats of parked cars. Or those other occasions when she repeated the same trick, but at the front entrance to Madam Helen St. Clair’s notorious city brothel.

Most disturbing to Judge Sayre was Zelda’s well-earned reputation for violating the time-honored codes of sexual propriety that seemed everywhere under attack by the time the opening shots were fired in World War I. Already a veritable legend among hundreds of well-heeled fraternity brothers as far and wide as the University of Alabama, Auburn University, and Georgia Tech, Zelda was “the most popular girl at every dance,” as a would-be suitor remembered years later.

Part of Zelda’s renown surely was owed to her habit of sneaking out of country club dances—and sometimes her bedroom window—to join Montgomery’s most eligible bachelors for a few hours of necking, petting, and drinking in secluded backseat venues. On more than a few occasions, the inviting aroma of pear trees, the dim glow of a half-moon, and the tentative sound of a boyfriend’s car horn were all the inspiration Zelda needed to walk quietly across her plain whitewashed room, draw open the curtains, and creep down to the tin roof that protected the Sayre family’s front porch.

After that, she was gone into the night.

During her four years at Sidney Lanier High School, Zelda was an average student, but she was well ahead of the learning curve in most other matters. She habitually rouged her cheeks and stenciled her eyes with mascara, giving her friends’ parents great cause for concern.

A regular at the local soda fountain, she alternated between double banana splits (innocuous) and a “dopes” (not so innocuous), a combination of Coca-Cola and aromatic spirits.

When the entire senior class cut school on April 1, it was Zelda who pooled everyone’s money and flirted with the nice agent at the Empire Theatre, who happily granted the students admission at a cut rate. And it was Zelda who triumphantly organized a group photo in front of the ticket box.

When her English teacher assigned a poetry-writing exercise for homework, Zelda immediately volunteered to read her original

composition—scratched out the next morning in homeroom—aloud.

I do love my Charlie so.

It nearly drives me wild.

I’m so glad that he’s my beau

And I’m his baby child!

It was a big hit with her classmates, but not exactly what the teacher was looking for.

For all of Zelda’s purported daring, Sara Mayfield, her loyal childhood friend, averred that she was no better or worse than most young women of her time. “Zelda would have been the last to deny that she danced cheek to cheek and did the Shimmy, the Charleston, and the Black Bottom,” Mayfield admitted. But “if she gave a demonstration of the Hula at a midterm dance at the University of Alabama, had not Alice Roosevelt, the President’s daughter, been similarly criticized for doing the same thing . . . ?”

To be sure, Zelda “rode behind her admirers . . . on their motorcycles with her arms around them, raised her hemlines to the knee, bobbed her hair, smoked, tippled, and kissed the boys goodbye.” But this sort of “flirtation was an old Southern custom; ‘going the limit’ was not. Zelda was a reigning beauty and ‘a knockout’ in the paleolithic slang of the day, far too popular to have ‘put out’ for her beaux, far too shrewd in the tactics and strategy of popularity to grant her favors to one suitor and thereby alienate a regiment of them.”

Maybe so, maybe not. But Zelda did her best to cultivate a scandalous reputation. She encouraged reports of skinny-dipping excursions and multiple romantic entanglements. During the summer, when it got too hot, she slipped out of her underwear and asked her date to hold it for the evening in his coat pocket. And at a legendary Christmas bop, when a chaperone reproached her for dancing too closely and too wantonly with her date, Zelda retaliated by swiping a band of mistletoe and pinning it to her backside.

Long after the last chords of the Jazz Age had been struck, Zelda admitted in her own autobiographical novel that “I never let them down on the dramatic possibilities of a scene—I give a damned good show.”

Scott Fitzgerald certainly thought so.

Just shy of his twenty-first birthday, the young army lieutenant was stationed at nearby Camp Sheridan, where he spent most of his time devouring novels and cavorting with the sons and daughters of Montgomery’s first citizens. Smartly clad in a new dress uniform, Fitzgerald cut an impressive figure. Shortly after the war, when Scott’s first book became a best-seller, an interviewer described him as bearing “the agreeable countenance of a young person who cheerfully regards himself as the center of everything.” His eyes were “blue and domineering,” his nose “Grecian and pleasantly snippy; mouth, ‘spoiled and alluring,’ like one of his own yellow-haired heroines; and he parts his wavy fair hair in the middle, as Amory Blaine”—the fictional hero of Fitzgerald’s first novel—“decided that all ‘slickers’ should do.”

Fitzgerald was a native of St. Paul, Minnesota, who had spent four years at Princeton without earning his undergraduate degree. An indifferent student, he received poor marks from his professors and made little contribution to classroom discussion. To his credit, Fitzgerald was an accomplished amateur playwright and a frequent contributor to the university literary magazine. But on balance, his academic career fell far short of even his expectations.

Lazy in all things but reading and writing, vaguely ambitious but hopelessly lacking direction, Fitzgerald escaped the indignity of a fifth year at Princeton by enlisting in the army in late 1917. First stationed at Fort Leavenworth for officer’s training, he made a poor impression on his platoon captain, a serious young West Point man named Dwight D. Eisenhower. Scott’s attention simply wasn’t on soldiering, and it showed. He fully expected that he would be sent to the European front, and fearing that he might return in a pine box, he accelerated work on his first novel, The Romantic Egotist. It consumed much of his time and all of his energy.

On short leave from the army in early 1918, Scott enjoyed a brief hiatus in Princeton, where he managed to finish the novel and send it off to an editor at Charles Scribner’s Sons. After reporting back for duty in March, he was transferred to the Forty-fifth Infantry Regiment at Camp Alexander in Kentucky. Though he was trained to lead a platoon, his commanding officers found Scott so deficient as a soldier that they consigned him to stateside duty—first at Camp Gordon in Georgia and then, in June 1918, at Camp Sheridan.

With his novel under review and combat service safely at bay, Fitzgerald was free to immerse himself in local revelries. Almost from the start, he began working his way through a list of Montgomery’s most eligible debutantes, generously supplied by Lawton Campbell, a local boy he had known at Princeton. In a more candid moment years later, Fitzgerald admitted that he had been naturally endowed with neither “great animal magnetism nor money,” two certain keys to success among the well-bred collegiate circles in which he moved back in the early days. Still, he knew that he had “good looks and intelligence,” qualities that generally helped him get the “top girl” wherever he went.

Lawton Campbell was several years older than Zelda Sayre and had left Montgomery before she entered high school; consequently, he didn’t include her on Scott’s roster of southern belles. It was purely by chance that she and Scott Fitzgerald happened upon each other that evening in July.

The moment his eyes locked on her, Scott was taken by Zelda’s beauty. Had he asked around, he would have learned of her dangerous reputation. As one contemporary remembered, “There were two kinds of girls, those who would ride with you in your automobile at night and the nice girls who wouldn’t. But Zelda didn’t seem to give a damn.”

At the first opportunity, Scott elbowed his way to her side and, finding that her dance card was full for the evening, asked if he might take her out after the country club festivities wound down. The faux East Coast drawl that he studiously cultivated at Princeton just barely concealed his flat Minnesota burr.

“I never make late dates with fast workers,” she replied sharply in the most properly southern of southern accents.

Nevertheless, she gave Scott her telephone number and subtly encouraged him to ply his charms another time.

Scott called Zelda at home the next day—and the next day after that, and again every day for the better part of two weeks until she relented. Not that it took a great deal of convincing. Scott was “a blond Adonis in a Brooks Brothers uniform,” one of their contemporaries remarked. He was, by Lawton Campbell’s estimation, “the handsomest boy I’d ever seen. He had yellow hair and lavender eyes” and a confident swagger that won over even his deepest skeptics.

In her autobiographical novel, Zelda evoked the sensation of dancing with Scott on one of their first dates. “[H]e smelled like new goods,” she wrote all those years later. “Being close to him, [my] face in the space between his ear and his stiff army collar was like being initiated into the subterranean reserves of a fine fabric store exuding the delicacy of cambrics and linen and luxury bound in bales.” Zelda was jealous of Scott’s “pale aloofness,” and when she watched him stroll arm in arm off the dance floor with other women, she felt a dull pang of resentment that he was “leading others than [me] into those cooler regions which he inhabited alone.”

To be fair, Zelda saw to it that Scott did most of the chasing. As one of Montgomery’s most popular debutantes, she already enjoyed scores of romantic opportunities from the usual college and business crowds. In normal times, Scott would have faced stiff competition from the likes of Dan Cody, the dashing young scion of a prominent Montgomery banking family, or Lloyd Hooper, an even wealthier son of an even wealthier Alabama line. Now, with America fully mobilized for war and thousands of doughboys in starched uniforms flooding Camp Sheridan, Zelda found herself one of the mostly hotly pursued belles in the state. Army aviators stationed at Camp Taylor honored her with elaborate aerial stunts and flyovers above the Sayre household, until an unfortunate pilot crashed his plane and died in a futile attempt to win Zelda’s affections. Army regulars staged a ceremonial drill on Pleasant Avenue in Zelda’s honor. Sara Mayfield claimed that when the war ended and all of Montgomery celebrated with a grand parade, “the military police had to break up the stag lines that crowded around her.”

By her own admission, Zelda’s attention wasn’t on school that year. There were too many “soldiers in town [and] I passed my time going to dances—always in love with somebody, dancing all night, and carrying on my school work just with [the] idea of finishing it.”

This fierce competition notwithstanding, within weeks of their first meeting Scott and Zelda fell deeply in love. Each weekend, Scott would hop the rickety old army bus at Camp Sheridan and ride it into downtown Montgomery; from there, he would take a short cab ride to 6 Pleasant Avenue and call on Zelda. They passed their days rocking quietly on the Sayres’ front porch swing and sipping cool drinks made of crushed ice and fruit. At night they danced away the hours at the country club, where Scott carved their initials in the front doorpost. Sometimes they strolled arm in arm around the pine groves that encircled the town. Scott joked that by the logic of both Keats and Browning, Zelda was destined to marry him. Good-naturedly, Zelda replied that Scott was an “educational feature; an overture to romance which no young lady should be without.”

That long Indian summer of 1918 would loom large in both their memories. Writing from her confinement in a mental hospital almost twenty years later, Zelda found that “at this dusty time of the year the flowers and trees take on the aspect of flowers and trees drifted from other summers.” The peculiar scent of pine needles evoked memories of “roads that cradled the happier suns of a long time ago.” She fondly bade Scott to recall the “night you gave me a birthday party and you were a young lieutenant and I was a fragrant phantom . . . it was a radiant night, a night of soft conspiracy and the trees agreed that it was all going to be for the best. . . . That’s the first time I ever said that in my life.”

Zelda’s eighteenth birthday fell on July 24, 1918, less than a month after they first met. If she and Scott didn’t consummate their relationship then, it’s almost certain they did so before the summer’s close. From an early age, Fitzgerald kept detailed scrapbooks that chronicled his life and his works in progress. An entry from 1935, containing notes for a short-story collection, reads: “After yielding she holds Philippe at bay like Zelda + me in summer 1917.” It was a slip of memory; he meant 1918. But this lone fragment, and Zelda’s later reminiscences, suggest that they slept together sometime before that November, when Scott left for Camp Mills, in New York, to await embarkation for Europe.

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

With its heady cocktail of storytelling and big ideas, "Flapper" is a dazzling look at the women who launched the first truly modern decade. 27 photos throughout.