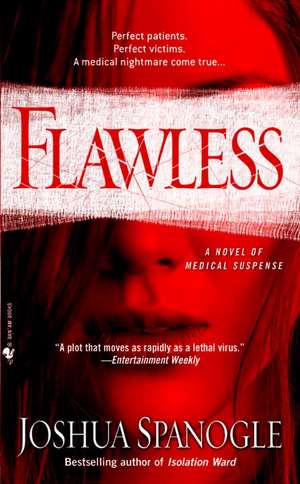

Flawless

Autor Joshua Spanogleen Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 feb 2008

As a circle of treachery tightens around Nate, and the woman he loves is thrust into the line of fire, patients surface with agonizing stories to tell. Nate is about to make the most startling discovery of all: a secret alliance between crime, science, and a billion-dollar industry determined to hide its victims at any price. For Nate, that price will be the one person most important to him—unless he can expose the flaw in a perfect conspiracy of medicine and murder.

From shocking evidence revealed under a microscope to the shattering testimony of those betrayed by the ruthlessness of the medical industry, Flawless takes us on a terrifying, adrenaline-charged journey. Taut, thrilling, and relentless, it will leave you pondering its questions long after the last page is turned.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 45.53 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 68

Preț estimativ în valută:

8.71€ • 9.00$ • 7.25£

8.71€ • 9.00$ • 7.25£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440242291

ISBN-10: 0440242290

Pagini: 560

Dimensiuni: 106 x 176 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0440242290

Pagini: 560

Dimensiuni: 106 x 176 x 31 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:Reprint

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

With his bestselling, explosive debut thriller, Isolation Ward, medical insider Joshua Spanogle earned comparisons to Michael Crichton—and wide acclaim for his ingenious blend of suspense, cutting-edge science, and raw emotion. Now Spanogle takes us into the dark heart of medicine to tell a terrifying story of a billion-dollar medical breakthrough—and the side effects it unleashes….

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter One

THE HEAT WOKE ME.

I became aware of perspiration through my scalp, of a rusty orange glow behind my closed lids. I opened my eyes and saw crisp light dance through a palm tree outside, saw it play across the living room floor. There was an immediate sense of disorientation: Palm tree? Living room?

Why was I on the couch?

Right. Brooke. Nasty fight.

I raised my head off the chenille pillow, felt as though someone were grinding my brain beneath their boot. Unwisely, I tried to remember events of the night before. First, dinner and a bottle of that high-alcohol zin California vintners seem to be addicted to these days. Then the party with Brooke's friends. The glass after glass of good Scotch pushed into my hand.

It was all coming back.

The friend of Brooke's friend--the lawyer in jeans and French cuffs who thought he knew how to fix health care in the country. He'd droned on about the free market and incentives and how forty-seven million uninsured "isn't really that many." Eventually, I couldn't take it anymore. I'd bellied up to the conversational bar, armed with a killer buzz and a self-righteous 'tude. I saw Brooke's face fall when I opened my mouth, but I couldn't stop myself. "Idiot" was mentioned somewhere along the way, then "do your homework," then "moron." The next thing I knew, Brooke's hand was tugging mine and we were at the door, saying our good-byes.

Oh, and after beating a retreat from the party--Brooke whispering to our host, "I'm so sorry, he's been under a lot of stress," me shooting back, "It's stressful teaching a rock to think"--we got into the car and I still couldn't quit. "What a dickhead," I said. "What a complete dickhead." Little did I know that the hostess of the party was trying to make the gent in the French cuffs.

Terrific work, McCormick.

I closed my eyes and tried to sleep again, but there was the sunshine and, now, some shuffling. The bedroom door opened, then the bathroom door opened and closed. Didn't even catch a glimpse of Brooke.

In my defense, my hard-drinking days were long gone, the guy was an idiot, and I actually had been under a lot of stress. I had just effected a cross-country transfer in life, from Atlanta to San Francisco. Not only was this a big red-state-to-blue-state shift, the move also marked a kind of a break point in my career. I'd been finishing up a two-year stint as an officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and would have been happy to work with the organization for a few more years. Initially, they said they'd love to have me stay at headquarters in Atlanta, that they wanted to groom me for more administrative duties. Not only did I not want to touch anything like an administrative duty, I certainly didn't want to be in Atlanta.

The humidity makes me break out.

Despite the offer of further employment at CDC, my ride there had been somewhat rocky. Granted, the year before, I got a few feathers in my cap for solving a case that extended from Baltimore to San Jose, but those feathers had been plucked from ruffled institutional poultry. Not to mention that I decided to blow off a meeting with my superiors--a meeting in Atlanta at which I was to be honored--following the whole tragic fiasco. Technically, I was AWOL at that time, since the CDC and U.S. Public Health Service still had some vestiges of the Navy from which they were born. That storm blew over when my boss got in touch with me at my rented vacation house and convinced me to be on the next plane back East if I ever wanted to have a career to gripe about. I returned to Atlanta for one day, then flew back to California to finish the vacation.

After that, the rest of my tenure as an EIS officer was a hodgepodge of the mundane and the exciting: work in the office, three weeks in Angola to help deal with the Marburg virus mess there. Crunching through databases one week, spraying bodies with bleach in 110-degree heat the next. Another day in the life, right? By the end of my two years, things actually seemed to be on the up-and-up. Negotiations about where I would find myself seemed to be going well; there were a couple of non-Atlanta positions in which I was interested, a couple of people who were interested in me filling those positions. At that time, though, CDC was under assault by an ideological executive branch filled with fanatics who had little use for the truth. Reports were being edited, science was being politicized, all that crap. Scientists and epidemiologists don't generally cotton to lying and manipulation, so CDC had been slowly bleeding good people. When a friend of mine quit in protest after crucial data in a report she wrote had been dropped--she'd shown that condom education had no effect on promiscuity--I followed her out the door. I can't abide idiocy, which can make for problems in a government employee.

On the personal front, my life was just about as complicated. Not that it was bad--it was actually quite good for a guy whose batting average with women hung in the low double digits. After an idyllic month seaside with Brooke, I went back to Atlanta. She stayed in California, grinding away at the Santa Clara Department of Public Health. Somehow, we managed to keep the bicoastal relationship alive for almost a year. A paycheck decimated by transcontinental plane tickets was proof of my feelings for the woman. When I finished with the EIS, I tried to get Brooke to move. Anywhere but Northern California, I begged her. The last place on the planet I wanted to be was the Bay Area; even Baghdad looked attractive by comparison. If push came to shove, I would have stayed in the Southeast, pimples be damned. San Francisco was a place so filled with personal baggage I got a backache just thinking about it. But Brooke was pretty well ensconced, so I moved west a month before that tete-a-tete with the moron lawyer. No job, no place of my own. I made the move for love.

It was, perhaps, another mistake.

"You going to look at apartments today?" Brooke asked.

She stood in the archway to the living room, arms crossed in front of that athletic body, blond hair pulled back in a ponytail. Tight white T-shirt. Cotton panties, no pants. She looked very sexy and very pissed.

"Subtle, Brooke."

"I just don't know if this is working," she said. "You living here."

I rolled my head on the pillow, toward the boxes and duffels piled against the wall of Brooke's living room. All my life, contained therein. "At least it will be cheap to get these back East."

"I don't mean here, California. I mean living here, here. My house. You know what I mean."

"I'm not living here, sweetie. Unless you consider my toothbrush in your bathroom living here."

"Nate . . ."

"Brooke . . ."

She sat on the chair at one end of the couch, affording me a generous glimpse of the panties. She caught me looking and crossed her legs.

"Okay," I said, "I may be having a little difficulty with the transition--"

"A little difficulty? You've already alienated half my social circle."

"Be a circle-half-full person, Brooke, not circle-half-empty."

"Can you stop joking for once? Jesus."

"I need a glass of water." With superhuman effort, I pulled myself off the couch and shuffled into the kitchen. I was worried my head might explode, which would mean quite a cleanup for Brooke and which would undoubtedly annoy her more. Brooke's cat, Buddy, skittered from the kitchen when he saw me, freaked maybe about the exploding head. I found water and Tylenol and shambled back to the sofa.

"I already apologized for last night," I said. "About two billion times. I'm not apologizing again."

"I'm not asking for another apology, Nathaniel." Nathaniel.

I took a big gulp of the water. "So what are you asking for?"

"I don't know." She looked around the house. It was a two-bedroom on the outskirts of Palo Alto, a town halfway between San Jose and San Francisco. The digs were nicer than my apartment in Atlanta, which looked like it had just rolled off a conveyor belt in Shanghai. No, Brooke's place was all hardwood floors, white walls, and good light. She'd done a decent amount of nesting, and the house had all the girl-touches: MoMA and Ansel Adams prints, high-maintenance plants, and, despite the cat's best efforts, not a speck of dust or hair to be found. Brooke was a public health doctor, after all. Oh, and then there were the bikes, the backpacks, the ice axe and climbing rope. Those things were, thank God, in the shed, so I wasn't constantly reminded that she had one-upped me in the masculinity department as well. I could still beat her at arm wrestling, though.

So, in terms of basic comfort, her place was ideal. Unfortunately, it was also near the university where I'd spent the glory days of my medical career before getting kicked out.

"I got this place because it was bigger," she said, "so, you know, if things worked out . . ."

My emotional antennae, numb as they are, sensed danger. "Things aren't working out?"

"No, it's not that. Or maybe it is that. I got it because I thought maybe you could stay . . . for a while. So there'd be enough room."

"I thought you got it because it was closer to San Francisco, where I was going to find an apartment."

"That, too."

"Well, which is it?"

"It's both, Nate. It can be both, can't it?"

"Sure, but maybe it would be better if we'd communicate these things."

"Would that have changed anything?"

"No, I guess not . . ." I geared up for some relationship-speak. "Look, we're just getting used to this. A year apart, Brooke, of course we're going to rub each other the wrong way sometimes. And yes, I had too much to drink last night, and yes, I was stupid enough to engage in a conversation about health care with an uninformed, know-it-all bonehead. I'm in a part of the country that has eons of painful history for me, I don't have a job, I'm trying to make it work with someone I know best from telephone calls. And all my crap fits into that Corolla outside. Of course there's going to be bumps."

"So this is about you? Your crap, your Corolla, your job? Why take it out on me and my friends? Why let it infect my life?"

Unwise for me to engage in emotional jujitsu with a master. Also, she was probably right.

"Okay, I'll try not to let the virus of my insecurity infect your life."

Brooke shook her head.

I said, "To answer your original question: I do have appointments to see places up in the city. Two of them. You want to come?"

"I'd love to, but I have to run the dishwasher." She smiled, the first real smile I'd seen from her in fifteen hours. "I'll come if you stop being so dramatic. 'Virus of my insecurity.' Please."

I rolled off the couch onto the floor and crawled to her, grunting like Igor. "Whatever you wish, Master. No drama. No insecurity virus, Master." Brooke giggled and kicked at me. "Yes, yes. Beat me, Master." I grabbed a leg and snaked my hand under the T-shirt, hooked my finger in the panties.

Then the goddamned cell phone went off.

"Must get phone, Master. Might be landlord calling about apartment."

I crawled to my jeans and fished out the phone.

"Is this Nate McCormick?"

I didn't recognize the number that popped up on the cell's caller ID. I didn't recognize the voice, but I didn't think it was a landlord; people trying to sell or lease me things usually buttered me up by calling me "Doctor."

I told him it was.

"Nate--it's Paul Murphy."

At that, my head cleared and my guts pulled tight, cinching down like a hangman's knot at the instant the trapdoor opens.

Chapter Two

PAUL MURPHY. NOT A NAME I'd heard in a long time. Not a name without its--how should I say?--its complexities.

"Paul," I said. "Murph. Long time."

"Ten years, by my count."

"God. Ten years."

"Ten years, yeah." He cleared his throat. "Uh, so how're you doing?"

"Fine," I said, looking at Brooke. "You?"

"I'm pretty good. Pretty good." But he didn't sound too convinced of it. When I knew him, back in med school, back in the dark days, Murph was one of those gregarious, hail-fellow-well-met guys.

He could keep a conversation rolling with an autistic.

"So what's up?" I asked.

"Oh, not much. Still working on the answer to cancer."

"You figure it out yet?"

"Yeah. Forty-two. That's the answer."

Both of us forced a laugh, and the conversation once again lost momentum.

"So, Murph, what's going on?"

"Oh, sorry. Yeah. I work for a biotech in South San Francisco. Two kids. A monster of a mortgage. The works. You still in Atlanta?"

"No. I'm out here now. Just moved."

"Oh, wow. Great. They said you left CDC, said you might be out here."

"Who said?"

"The CDC. That's how I got this number."

"They're not supposed to give it out."

"I know a guy who works there. Vik Patel. You know him?"

"No."

"Good guy. He was at school . . . He came a little after-- Anyway, hope it's not a problem I called. I told him it was real important we talk . . ."

Again, that lull. If the conversation kept stalling like this it would be a problem. I was fighting a mother of a hangover, and was having trouble navigating a stilted exchange with a guy I hadn't seen in a decade, with a guy who, back then, I would have loved to see dangling from the rafters. On the other hand, what did I have to do? See a couple apartments? Real vital stuff.

Plus, whatever had transpired between Paul Murphy and me in the past, he had once been a friend. And something was obviously bugging the guy.

"So, Murph, what's up?" I asked for the third time.

"I got some questions, Nate. You have time?"

"Sure. Shoot."

"I was hoping we could get together. Not over the phone."

"No problem. I have a wide open schedule next week--"

"I was hoping to see you today. It's kind of important."

"Uh, okay. I have some things later this morning--"

"Perfect. How's three o'clock?"

"I have a couple appointments in San Francisco--"

"Great. I have to drop my son off at a soccer game in the city. Sorry to push, Nate, really, but you know . . . You deal with this stuff all the time."

"I don't really know since I don't know, you know?" I said. Red flags were springing up all over the place--the odd nature of the conversation, Murph's edginess, the fact that he'd called me, despite our history.

"Three o'clock, right?" He gave me the address of a coffee shop in San Francisco's Haight district.

"Sure. Three o'clock." I was about to hang up, when something struck me. "Hey, Murph, how'd you know I was at CDC?"

"That Chimeragen thing last year, Nate. It was all over the papers here. Man, you sure had your fifteen minutes."

From the Hardcover edition.

THE HEAT WOKE ME.

I became aware of perspiration through my scalp, of a rusty orange glow behind my closed lids. I opened my eyes and saw crisp light dance through a palm tree outside, saw it play across the living room floor. There was an immediate sense of disorientation: Palm tree? Living room?

Why was I on the couch?

Right. Brooke. Nasty fight.

I raised my head off the chenille pillow, felt as though someone were grinding my brain beneath their boot. Unwisely, I tried to remember events of the night before. First, dinner and a bottle of that high-alcohol zin California vintners seem to be addicted to these days. Then the party with Brooke's friends. The glass after glass of good Scotch pushed into my hand.

It was all coming back.

The friend of Brooke's friend--the lawyer in jeans and French cuffs who thought he knew how to fix health care in the country. He'd droned on about the free market and incentives and how forty-seven million uninsured "isn't really that many." Eventually, I couldn't take it anymore. I'd bellied up to the conversational bar, armed with a killer buzz and a self-righteous 'tude. I saw Brooke's face fall when I opened my mouth, but I couldn't stop myself. "Idiot" was mentioned somewhere along the way, then "do your homework," then "moron." The next thing I knew, Brooke's hand was tugging mine and we were at the door, saying our good-byes.

Oh, and after beating a retreat from the party--Brooke whispering to our host, "I'm so sorry, he's been under a lot of stress," me shooting back, "It's stressful teaching a rock to think"--we got into the car and I still couldn't quit. "What a dickhead," I said. "What a complete dickhead." Little did I know that the hostess of the party was trying to make the gent in the French cuffs.

Terrific work, McCormick.

I closed my eyes and tried to sleep again, but there was the sunshine and, now, some shuffling. The bedroom door opened, then the bathroom door opened and closed. Didn't even catch a glimpse of Brooke.

In my defense, my hard-drinking days were long gone, the guy was an idiot, and I actually had been under a lot of stress. I had just effected a cross-country transfer in life, from Atlanta to San Francisco. Not only was this a big red-state-to-blue-state shift, the move also marked a kind of a break point in my career. I'd been finishing up a two-year stint as an officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and would have been happy to work with the organization for a few more years. Initially, they said they'd love to have me stay at headquarters in Atlanta, that they wanted to groom me for more administrative duties. Not only did I not want to touch anything like an administrative duty, I certainly didn't want to be in Atlanta.

The humidity makes me break out.

Despite the offer of further employment at CDC, my ride there had been somewhat rocky. Granted, the year before, I got a few feathers in my cap for solving a case that extended from Baltimore to San Jose, but those feathers had been plucked from ruffled institutional poultry. Not to mention that I decided to blow off a meeting with my superiors--a meeting in Atlanta at which I was to be honored--following the whole tragic fiasco. Technically, I was AWOL at that time, since the CDC and U.S. Public Health Service still had some vestiges of the Navy from which they were born. That storm blew over when my boss got in touch with me at my rented vacation house and convinced me to be on the next plane back East if I ever wanted to have a career to gripe about. I returned to Atlanta for one day, then flew back to California to finish the vacation.

After that, the rest of my tenure as an EIS officer was a hodgepodge of the mundane and the exciting: work in the office, three weeks in Angola to help deal with the Marburg virus mess there. Crunching through databases one week, spraying bodies with bleach in 110-degree heat the next. Another day in the life, right? By the end of my two years, things actually seemed to be on the up-and-up. Negotiations about where I would find myself seemed to be going well; there were a couple of non-Atlanta positions in which I was interested, a couple of people who were interested in me filling those positions. At that time, though, CDC was under assault by an ideological executive branch filled with fanatics who had little use for the truth. Reports were being edited, science was being politicized, all that crap. Scientists and epidemiologists don't generally cotton to lying and manipulation, so CDC had been slowly bleeding good people. When a friend of mine quit in protest after crucial data in a report she wrote had been dropped--she'd shown that condom education had no effect on promiscuity--I followed her out the door. I can't abide idiocy, which can make for problems in a government employee.

On the personal front, my life was just about as complicated. Not that it was bad--it was actually quite good for a guy whose batting average with women hung in the low double digits. After an idyllic month seaside with Brooke, I went back to Atlanta. She stayed in California, grinding away at the Santa Clara Department of Public Health. Somehow, we managed to keep the bicoastal relationship alive for almost a year. A paycheck decimated by transcontinental plane tickets was proof of my feelings for the woman. When I finished with the EIS, I tried to get Brooke to move. Anywhere but Northern California, I begged her. The last place on the planet I wanted to be was the Bay Area; even Baghdad looked attractive by comparison. If push came to shove, I would have stayed in the Southeast, pimples be damned. San Francisco was a place so filled with personal baggage I got a backache just thinking about it. But Brooke was pretty well ensconced, so I moved west a month before that tete-a-tete with the moron lawyer. No job, no place of my own. I made the move for love.

It was, perhaps, another mistake.

"You going to look at apartments today?" Brooke asked.

She stood in the archway to the living room, arms crossed in front of that athletic body, blond hair pulled back in a ponytail. Tight white T-shirt. Cotton panties, no pants. She looked very sexy and very pissed.

"Subtle, Brooke."

"I just don't know if this is working," she said. "You living here."

I rolled my head on the pillow, toward the boxes and duffels piled against the wall of Brooke's living room. All my life, contained therein. "At least it will be cheap to get these back East."

"I don't mean here, California. I mean living here, here. My house. You know what I mean."

"I'm not living here, sweetie. Unless you consider my toothbrush in your bathroom living here."

"Nate . . ."

"Brooke . . ."

She sat on the chair at one end of the couch, affording me a generous glimpse of the panties. She caught me looking and crossed her legs.

"Okay," I said, "I may be having a little difficulty with the transition--"

"A little difficulty? You've already alienated half my social circle."

"Be a circle-half-full person, Brooke, not circle-half-empty."

"Can you stop joking for once? Jesus."

"I need a glass of water." With superhuman effort, I pulled myself off the couch and shuffled into the kitchen. I was worried my head might explode, which would mean quite a cleanup for Brooke and which would undoubtedly annoy her more. Brooke's cat, Buddy, skittered from the kitchen when he saw me, freaked maybe about the exploding head. I found water and Tylenol and shambled back to the sofa.

"I already apologized for last night," I said. "About two billion times. I'm not apologizing again."

"I'm not asking for another apology, Nathaniel." Nathaniel.

I took a big gulp of the water. "So what are you asking for?"

"I don't know." She looked around the house. It was a two-bedroom on the outskirts of Palo Alto, a town halfway between San Jose and San Francisco. The digs were nicer than my apartment in Atlanta, which looked like it had just rolled off a conveyor belt in Shanghai. No, Brooke's place was all hardwood floors, white walls, and good light. She'd done a decent amount of nesting, and the house had all the girl-touches: MoMA and Ansel Adams prints, high-maintenance plants, and, despite the cat's best efforts, not a speck of dust or hair to be found. Brooke was a public health doctor, after all. Oh, and then there were the bikes, the backpacks, the ice axe and climbing rope. Those things were, thank God, in the shed, so I wasn't constantly reminded that she had one-upped me in the masculinity department as well. I could still beat her at arm wrestling, though.

So, in terms of basic comfort, her place was ideal. Unfortunately, it was also near the university where I'd spent the glory days of my medical career before getting kicked out.

"I got this place because it was bigger," she said, "so, you know, if things worked out . . ."

My emotional antennae, numb as they are, sensed danger. "Things aren't working out?"

"No, it's not that. Or maybe it is that. I got it because I thought maybe you could stay . . . for a while. So there'd be enough room."

"I thought you got it because it was closer to San Francisco, where I was going to find an apartment."

"That, too."

"Well, which is it?"

"It's both, Nate. It can be both, can't it?"

"Sure, but maybe it would be better if we'd communicate these things."

"Would that have changed anything?"

"No, I guess not . . ." I geared up for some relationship-speak. "Look, we're just getting used to this. A year apart, Brooke, of course we're going to rub each other the wrong way sometimes. And yes, I had too much to drink last night, and yes, I was stupid enough to engage in a conversation about health care with an uninformed, know-it-all bonehead. I'm in a part of the country that has eons of painful history for me, I don't have a job, I'm trying to make it work with someone I know best from telephone calls. And all my crap fits into that Corolla outside. Of course there's going to be bumps."

"So this is about you? Your crap, your Corolla, your job? Why take it out on me and my friends? Why let it infect my life?"

Unwise for me to engage in emotional jujitsu with a master. Also, she was probably right.

"Okay, I'll try not to let the virus of my insecurity infect your life."

Brooke shook her head.

I said, "To answer your original question: I do have appointments to see places up in the city. Two of them. You want to come?"

"I'd love to, but I have to run the dishwasher." She smiled, the first real smile I'd seen from her in fifteen hours. "I'll come if you stop being so dramatic. 'Virus of my insecurity.' Please."

I rolled off the couch onto the floor and crawled to her, grunting like Igor. "Whatever you wish, Master. No drama. No insecurity virus, Master." Brooke giggled and kicked at me. "Yes, yes. Beat me, Master." I grabbed a leg and snaked my hand under the T-shirt, hooked my finger in the panties.

Then the goddamned cell phone went off.

"Must get phone, Master. Might be landlord calling about apartment."

I crawled to my jeans and fished out the phone.

"Is this Nate McCormick?"

I didn't recognize the number that popped up on the cell's caller ID. I didn't recognize the voice, but I didn't think it was a landlord; people trying to sell or lease me things usually buttered me up by calling me "Doctor."

I told him it was.

"Nate--it's Paul Murphy."

At that, my head cleared and my guts pulled tight, cinching down like a hangman's knot at the instant the trapdoor opens.

Chapter Two

PAUL MURPHY. NOT A NAME I'd heard in a long time. Not a name without its--how should I say?--its complexities.

"Paul," I said. "Murph. Long time."

"Ten years, by my count."

"God. Ten years."

"Ten years, yeah." He cleared his throat. "Uh, so how're you doing?"

"Fine," I said, looking at Brooke. "You?"

"I'm pretty good. Pretty good." But he didn't sound too convinced of it. When I knew him, back in med school, back in the dark days, Murph was one of those gregarious, hail-fellow-well-met guys.

He could keep a conversation rolling with an autistic.

"So what's up?" I asked.

"Oh, not much. Still working on the answer to cancer."

"You figure it out yet?"

"Yeah. Forty-two. That's the answer."

Both of us forced a laugh, and the conversation once again lost momentum.

"So, Murph, what's going on?"

"Oh, sorry. Yeah. I work for a biotech in South San Francisco. Two kids. A monster of a mortgage. The works. You still in Atlanta?"

"No. I'm out here now. Just moved."

"Oh, wow. Great. They said you left CDC, said you might be out here."

"Who said?"

"The CDC. That's how I got this number."

"They're not supposed to give it out."

"I know a guy who works there. Vik Patel. You know him?"

"No."

"Good guy. He was at school . . . He came a little after-- Anyway, hope it's not a problem I called. I told him it was real important we talk . . ."

Again, that lull. If the conversation kept stalling like this it would be a problem. I was fighting a mother of a hangover, and was having trouble navigating a stilted exchange with a guy I hadn't seen in a decade, with a guy who, back then, I would have loved to see dangling from the rafters. On the other hand, what did I have to do? See a couple apartments? Real vital stuff.

Plus, whatever had transpired between Paul Murphy and me in the past, he had once been a friend. And something was obviously bugging the guy.

"So, Murph, what's up?" I asked for the third time.

"I got some questions, Nate. You have time?"

"Sure. Shoot."

"I was hoping we could get together. Not over the phone."

"No problem. I have a wide open schedule next week--"

"I was hoping to see you today. It's kind of important."

"Uh, okay. I have some things later this morning--"

"Perfect. How's three o'clock?"

"I have a couple appointments in San Francisco--"

"Great. I have to drop my son off at a soccer game in the city. Sorry to push, Nate, really, but you know . . . You deal with this stuff all the time."

"I don't really know since I don't know, you know?" I said. Red flags were springing up all over the place--the odd nature of the conversation, Murph's edginess, the fact that he'd called me, despite our history.

"Three o'clock, right?" He gave me the address of a coffee shop in San Francisco's Haight district.

"Sure. Three o'clock." I was about to hang up, when something struck me. "Hey, Murph, how'd you know I was at CDC?"

"That Chimeragen thing last year, Nate. It was all over the papers here. Man, you sure had your fifteen minutes."

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

This follow-up to Spanogle's bestselling debut "Isolation Ward" plunges readers into the dark heart of medicine's most lucrative industry and depicts a harrowing race to expose the crimes that lay beneath its skin.