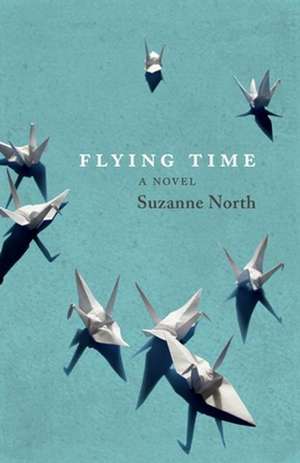

Flying Time

Autor Suzanne Northen Limba Engleză Paperback – 8 apr 2014

In 1939, Kay Jeynes, a lively, ambitious young working-class woman, goes to work for the only Japanese businessman in town, the elderly, wealthy, Oxford-educated Mr. Miyashita. Despite differences in their age, race, and class, a friendship develops between them in the peaceful vacuum of Mr. Miyashita’s office. But outside, on the city streets, a dark chapter in recent history is taking shape. As war looms, relations between North America and Japan grow steadily worse. Travel becomes impossible for Mr. Miyashita, so he asks Kay to cross the Pacific Ocean to retrieve a family heirloom, even as the Imperial Navy is maneuvering into position for the attack on Pearl Harbor. On this journey, Kay commits some seemingly small sins of omission. But in the paranoid climate of the times, these little white lies put Mr. Miyashita at risk of being arrested as a spy.

Preț: 86.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 130

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.53€ • 17.37$ • 13.90£

16.53€ • 17.37$ • 13.90£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781927366233

ISBN-10: 1927366232

Pagini: 312

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Brindle & Glass

Locul publicării:Canada

ISBN-10: 1927366232

Pagini: 312

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Grey Stone Books

Colecția Brindle & Glass

Locul publicării:Canada

Recenzii

Winner of the 2015 Saskatchewan Book Awards University of Regina Book of the Year Award.

Flying Time shortlisted for the Saskatchewan Book Awards: the University of Regina Book of the Year, the City of Regina Fiction Award, and the City of Saskatoon and Public Library Saskatoon Book Award.

"While [Suzanne North] is delivering a wealth of history, geology, art and Canada during the war, she also serves up a cracking good . . . rich memoir of an interesting life." —Calgary Herald

"Flying Time is an example of what literary historical fiction does well: provides a snapshot of a time and place through the small evolutions in relationships in a clearly defined context. North’s evocation of Calgary in 1939 is masterly, a clear sketch that is never too heavy on detail. Her writing style is fluid, chatty, and engaging, and the pages of this novel flew by." —Historical Novels Review

"Flying Time is not a flattering portrayal of Canada. It takes a hard, critical look at the undercurrents of racial tension that cut the [Japanese people] out of Calgary society, and the government-endorsed racism that saw them and thousands like them interned and their possessions sold off years later." —The National Post

"North, an accomplished mystery writer, has crafted a very readable story, and has a deft touch with dialog. She has done some credible research into a long-past time and place in bringing this story to life." —Pan Am Historical Society

"North has a completely engaging style." —The Saskatoon StarPhoenix

"Flying Time first captures and holds interest with its beautiful story-telling and then takes a suspenseful turn, leading it to 'can't-put-it-down' territory." —Alberta Views

"Flying Time is about how people used to talk, how they used to think. It’s about how a city used to be. It’s a story about memory, of civic and national tragedy, set against the epochs of geological time that have been brushed to the surface." —The Winnipeg Review

"Suzanne North’s Flying Time is a beautiful novel, brimming with intelligence, heart and wit. At the centre of the novel is protagonist Kay Jeynes’ journey from San Francisco to Hong Kong on the Pan American flying boat. Kay is fundamentally changed by what the trip teaches her about love, loss and life. Flying Time is transformative for readers too. Don’t miss the experience!" —Gail Bowen, author of the Joanne Kilbourn Shreve mystery series

"Anyone who has read Suzanne North’s mysteries knows that she can spin a great yarn. In Flying Time, she reveals herself to be, quite simply, a wonderful writer. Her new novel is filled with unforgettable characters in a richly imagined world. The result is original, genuinely moving and completely enjoyable." —Candace Savage, author of A Geography of Blood

Flying Time shortlisted for the Saskatchewan Book Awards: the University of Regina Book of the Year, the City of Regina Fiction Award, and the City of Saskatoon and Public Library Saskatoon Book Award.

"While [Suzanne North] is delivering a wealth of history, geology, art and Canada during the war, she also serves up a cracking good . . . rich memoir of an interesting life." —Calgary Herald

"Flying Time is an example of what literary historical fiction does well: provides a snapshot of a time and place through the small evolutions in relationships in a clearly defined context. North’s evocation of Calgary in 1939 is masterly, a clear sketch that is never too heavy on detail. Her writing style is fluid, chatty, and engaging, and the pages of this novel flew by." —Historical Novels Review

"Flying Time is not a flattering portrayal of Canada. It takes a hard, critical look at the undercurrents of racial tension that cut the [Japanese people] out of Calgary society, and the government-endorsed racism that saw them and thousands like them interned and their possessions sold off years later." —The National Post

"North, an accomplished mystery writer, has crafted a very readable story, and has a deft touch with dialog. She has done some credible research into a long-past time and place in bringing this story to life." —Pan Am Historical Society

"North has a completely engaging style." —The Saskatoon StarPhoenix

"Flying Time first captures and holds interest with its beautiful story-telling and then takes a suspenseful turn, leading it to 'can't-put-it-down' territory." —Alberta Views

"Flying Time is about how people used to talk, how they used to think. It’s about how a city used to be. It’s a story about memory, of civic and national tragedy, set against the epochs of geological time that have been brushed to the surface." —The Winnipeg Review

"Suzanne North’s Flying Time is a beautiful novel, brimming with intelligence, heart and wit. At the centre of the novel is protagonist Kay Jeynes’ journey from San Francisco to Hong Kong on the Pan American flying boat. Kay is fundamentally changed by what the trip teaches her about love, loss and life. Flying Time is transformative for readers too. Don’t miss the experience!" —Gail Bowen, author of the Joanne Kilbourn Shreve mystery series

"Anyone who has read Suzanne North’s mysteries knows that she can spin a great yarn. In Flying Time, she reveals herself to be, quite simply, a wonderful writer. Her new novel is filled with unforgettable characters in a richly imagined world. The result is original, genuinely moving and completely enjoyable." —Candace Savage, author of A Geography of Blood

Notă biografică

Suzanne North is the author of the Phoebe Fairfax mystery series and has written for various magazines and television programs, as well as for documentary films. She lives in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Extras

Assignment #1

FILL FIVE PAGES

I’m waiting for Meggie to finish putting on her makeup. Our memoir writing class starts at two, and it’s already one forty-five. Nothing much happens around here before two because we all take a nap after lunch. Around half past one we get helped up for the second time in the day, have a pee and a wash, and struggle into our public selves or what’s left of them. Meggie always repaints. She never leaves her room in anything but full makeup and I do mean full—foundation, eye shadow, mascara, blusher. You name it, and Meggie’s been slapping it on since the day she left the convent school—and that’s a good seventy years, even if you spot her a few. She’s here because she had a stroke. She’s doing pretty well, but the left corner of her mouth still droops a little so she paints it back where it belongs with her trusty tube of Scarlet Passion. Her hands shake too, so it’s largely a matter of chance where everything ends up. But, what the hell, Meggie thinks it’s important, and I’m beginning to agree. She calls her full makeup job showing the flag.

Today we are off to review the difference between memoir and autobiography. As far as I can figure, from what our instructor Janice said last time, your memory doesn’t have to be so hot to write memoirs. It’s how you remember your life that counts, not the dates and facts and figures that measure it out. This is an encouraging point to make if you’re teaching a class where half your students couldn’t tell you what they ate for dinner last night without prompting from the audience. But even if we can’t remember yesterday worth a damn, most of us can tell you what the weather was like on our sixteenth birthday, or at least what we think the weather was like. That, in a nutshell, is the difference between memoir and autobiography. Write a memoir and it rains or shines as you recall. Write autobiography and you’re in the public library looking up old weather reports.

Which reminds me: last class Janice read us part of an essay on how to write. It was by some American mystery author who says you should never start a story with the weather. What a crock. In Calgary we never start anything without the weather. Even Meggie and I talk about the weather, and we haven’t been outside since the Labour Day blizzard. Meggie says it was just a brush of wet snow, but it looked like a blizzard to me. And, in my memoirs, I get to call the meteorological shots. Not that these are my actual memoirs. They’re just part of the assignment Janice set for us this week. We are to write the first thing that comes into our heads and keep on writing until we’ve filled at least five pages of our notebooks. We’re not to worry about grammar or spelling because this is only an exercise to get us started. It’s supposed to limber up our writing muscles, warm us up so we’re ready to tackle the real thing. Janice says filling five pages should give us the same great feeling that a physical workout gives our flesh and blood muscles. I guess Janice never spent a morning in rehab.

Meggie is done dabbing, so we’re ready to roll. Literally. Meggie pushes my wheelchair, and I call directions because she refuses to hide her eye makeup behind glasses. I won’t say she’s blind as a bat without them, but she could give Mr. Magoo a run for his money. My eyes are fine since I had my cataracts done, so the no-glasses business is okay with me as long as she turns when I tell her and we don’t run into walls. Our arrangement suits Meggie too, because my chair makes a good substitute for her walker, which she hates using, and I mean hates as in loathes and detests. I don’t really understand why she feels like this because from where I’m sitting, a walker looks like a pretty good deal. The prospect of getting out of this chair and being mobile again is what gets me through rehab mornings. I’ve promised myself that I’ll be galloping around here on a walker of my own by Halloween and back home before Christmas.

So off we go. Meggie says we look like something you’d see in a bad stretch at the Stampede parade—an old clown pushing a bag of rags in a wheelie bin.

Time to navigate.

Assignment #2

WHAT WAS THE MOST IMPORTANT DAY OF YOUR LIFE?

that’s our assignment for this week. I suspect your children may never speak to you again if you don’t make it the day they were born or the day you met their father. Meggie says don’t show them what you’ve written. Eventually, when you’re off warbling alto in the feathered choir, you won’t be around to speak to anyway, so why worry? After a few swigs of gin and tonic, I found myself agreeing with her. Give the pair of us a second gin, and we’d have been raring to publish in the Herald and be damned, but it was time for dinner—that’s five o’clock here at Gimpville—so we tottered off to our macaroni and cheese. Well, some of us wheeled off, if you’re going to be a stickler for accuracy.

By the way, this assignment is only another exercise, not our real memoirs. I’m beginning to wonder when we’ll get to those. Someone should tell Janice that around here it doesn’t do to dawdle. I don’t think she understands that if we don’t get down to business soon, some of us may reach The End before our memoirs do. All in all though, I have to admit I only signed up for the class so I’d have something to occupy my mind until I go home. Hang around this place long enough and you realize that “dying of boredom” is not just an expression.

I can see I’m going to have to watch myself. That boredom business sounded pretty negative, didn’t it? I vowed when I had to come to Foothills Sunset that I wouldn’t be a whiner. I fell off a chair and broke a few bits and pieces. Nothing will change that. But if you give in and start to dwell on all the things that get you down, you’ll only make yourself miserable and go gaga quicker. At least that’s what Meggie claims. She’s been here longer than me and says that she’s seen it happen more than once. According to her, it’s whine today and wither away tomorrow. So get well, go home, get on with my life.

That’s the plan. In the meantime, I’ve decided to go all Norman Vincent Peale and think positively.

All right. Time to get organized and buckle down to this Most Important Day stuff.

For me, there’s no thinking required. The most important day of my life was the day I went to work for Mr. Miyashita. Period. It certainly wasn’t something I’d planned on doing. Strange how a decision made on impulse, a morning’s whim really, can have such a profound effect on the rest of your life. I’m such a dithery old thing now that my spur-of-the-moment choice to take the job seems nothing short of miraculous. But on that winter morning all those years ago, it was simply a case of boredom meets opportunity. And what an opportunity! My time with Mr. Miyashita opened a new world to me, a world I could not have imagined before I met him. Thanks to him, I got an education, one that instilled in me an intellectual curiosity that I like to think has not diminished over the years. He also sent me on the greatest adventure of my life, a trip to Hong Kong on the Pan American flying boat in the fall of 1941. That journey changed my life, although if I’m to be honest, I’d have to admit not all the changes were happy ones. Still, it was an adventure on a grand scale, and I got to live it. How many people can say that?

Compared to my days at Miyashita Industries, I suppose the rest of my life has been pretty ordinary. Not that it’s been an unhappy life. Far from it. On the whole, I’d say I’ve had more than my share of happiness—or at least as much as anyone with a brain and a conscience can reasonably expect. But no one who has been around as long as I have can escape at least a small helping of the misery that the world has on constant offer, especially those of us who lived through the war. Believe me, in the months following my trip to Hong Kong, sometimes my helping didn’t feel all that small. The morning I stood and watched a train take the Miyashitas away to the New Denver camp was the morning I learned what it means to be sick at heart.

There I go, rambling all over the place again. One thing I know with absolute certainty is that the ability to concentrate definitely diminishes with age. At least it has in my case. I can see that from now on I’m going to have to do my best to collect my thoughts and begin at the beginning if I want the rest of this assignment to make any sense.

I turned nineteen in February of 1939. I still lived at home with my parents and my brother Charlie who was two years younger than me. I’d been working as a typist at the Greer & Western Coal Company for a little over five months. Greer & Western is long gone, but back then it was a thriving concern and our department was kept very busy. Still, typing is typing, and my days had become so routine that those five months felt more like five years. Every morning Mum packed me a paper bag lunch, and every morning I’d catch the streetcar from east Calgary to Greer & Western’s downtown office. There, every morning on the dot of eight-thirty, I’d sit down at a desk in a room with three other girls, lift the cover off my Underwood and go to work. I’d type until lunch, then after lunch I’d type some more. At five-thirty I’d cover my machine and catch the street car home. Same thing day in day out, except on Saturdays when the office closed at noon. It was about as exciting as our days here at Foothills Sunset. But you have to keep in mind that this was at the end of the Great Depression when you were lucky to have a job at all, as my dad was so fond of telling me. Especially if you were a woman. He always added that.

Most of my time at Greer & Western is now a blur of indistinguishable days, except for the Thursday I got the job with Mr. Miyashita. I’ll say this for Janice, until I began to work on her assignment, I had no idea that even its smallest details had stayed with me all these years. Startling to be caught unaware by your own memory, ambushed by colours and smells and sounds rushing in all of a tumble, from God knows where. Made me feel a bit shaky at first to discover that whole day still rattling around in my old brain.

When I said goodbye to Mum that morning, the mercury in the thermometer outside our kitchen window huddled down near the forty below mark. With every drop of moisture frozen from it, the air was so dry that little snaps of static electricity sparked off everything I touched. I even got a shock from Mum when she kissed me goodbye. It was only two blocks from our house to the streetcar stop, but it always felt farther when I was wearing my winter gear. That morning, I’d piled on an extra sweater, my heavy overcoat, two pairs of mittens, wool stockings and felt-lined boots. A wool toque pulled down over my ears and a big scarf pulled up over my nose completed the ensemble. God, what a lot of effort it took to go out in the cold back then. If you ask me, down-filled wind-proofs, all warm air and no substance, are one of the wonders of the modern world, and Thinsulate is a preview of heaven. I only had to wait for the streetcar a minute or two, but by the time it trundled up to our stop my fingers ached and my toes had begun to numb. A gust of air stirred up by the slowing car made my eyes water. Tears trickled down my cheeks and froze the instant they hit the scarf.

The ride from our house to downtown took fifteen minutes. That morning, frost on the overhead wires made the trolleys a little temperamental, but we still pulled up to my stop by The Hudson’s Bay at eight twenty, right on time. Greer & Western Coal occupied the top two floors of a brick building on 9th Avenue across the street from the Palliser Hotel, so ten minutes left ample time to walk there and get settled at my desk.

Despite the bitter cold, it was a relief when the driver opened the doors and I stepped out into fresh air, away from the fug of cigarette smoke, old sweat and wet wool that hung in the crowded cars on bitter days. Sometimes, depending on where you sat, you got whiffs of the coal fire in the driver’s little heater, and in the evening, the reek of fish and chips in their greasy wrappings, riding home for someone’s supper. Those fifteen minutes between home and downtown with all the windows shut could leave you feeling pretty queasy, especially if some man at the back in the smoking compartment lit a cigar. Matter of fact, just sitting here thinking about it is enough to make my stomach churn. Or maybe what’s really upsetting me is having to admit that I remember a morning all those years ago more vividly than any morning last week. That is one of the classic signs of old age, and it’s supposed to happen to other people, not to me.

I see me at my desk in a room with high ceilings and three tall sash windows. I hear the clatter of typewriters punctuated by the bangs and hisses of reluctant pipes as steam blasts through them on its way to the radiators. Again the smells. This time it’s clouds of Evening in Paris wafting off to battle the powerful forces of Raleigh’s Medicated Ointment and Life Buoy soap. The lower panes of the windows glitter with frost ferns while the upper glass remains clear and the morning sun shafts through, turning dust motes to floating specks of light and warming my shoulders as I type a letter to the transportation manager of the Portland Distributing Company on the subject of the proposed delivery date for a shipment of Drumheller bituminous.

The four of us had been at work for an hour. I had just put a new sheet of carbon paper between Greer & Western’s best linen bond and the cheap stuff we used for copies, when the big boss, Mr. Calthorpe himself, appeared at the typing room door. Everyone stopped working and looked up as he creaked across the oiled hardwood to the front of the room, followed by Miss Bayliss, the Simona Legree of the typing pool.

“Girls! Your attention!” Miss Bayliss ordered in her clipped and chilly tones. Since this was the first time Greer & Western’s president had ever set foot in the typing room, we knew it must be something important.

“Good morning girls,” Mr. Calthorpe began. His smile was genial if a trifle strained. “I’ve come to ask a favour of you. A friend of Greer & Western’s is in difficulty, and I’m hoping one of you young ladies will be able to help us help him.” He paused for effect, letting us prepare for the enormity of what he was about to say.

“As you may already know, Mr. Hero Miyashita is the head of the Canadian branch of Miyashita Industries. His private secretary was taken ill a few weeks ago and has had to return home to Japan. Until the company can arrange for a new man to be sent from their headquarters in Hiroshima, Mr. Miyashita is in need of some crackerjack secretarial help. That’s why I’m here today. I have come to ask one of you charming and talented young ladies to volunteer to work for Miyashita Industries. Of course, it would be a temporary arrangement, a few months’ secondment to tide Mr. Miyashita over until his new permanent secretary arrives.”

FILL FIVE PAGES

I’m waiting for Meggie to finish putting on her makeup. Our memoir writing class starts at two, and it’s already one forty-five. Nothing much happens around here before two because we all take a nap after lunch. Around half past one we get helped up for the second time in the day, have a pee and a wash, and struggle into our public selves or what’s left of them. Meggie always repaints. She never leaves her room in anything but full makeup and I do mean full—foundation, eye shadow, mascara, blusher. You name it, and Meggie’s been slapping it on since the day she left the convent school—and that’s a good seventy years, even if you spot her a few. She’s here because she had a stroke. She’s doing pretty well, but the left corner of her mouth still droops a little so she paints it back where it belongs with her trusty tube of Scarlet Passion. Her hands shake too, so it’s largely a matter of chance where everything ends up. But, what the hell, Meggie thinks it’s important, and I’m beginning to agree. She calls her full makeup job showing the flag.

Today we are off to review the difference between memoir and autobiography. As far as I can figure, from what our instructor Janice said last time, your memory doesn’t have to be so hot to write memoirs. It’s how you remember your life that counts, not the dates and facts and figures that measure it out. This is an encouraging point to make if you’re teaching a class where half your students couldn’t tell you what they ate for dinner last night without prompting from the audience. But even if we can’t remember yesterday worth a damn, most of us can tell you what the weather was like on our sixteenth birthday, or at least what we think the weather was like. That, in a nutshell, is the difference between memoir and autobiography. Write a memoir and it rains or shines as you recall. Write autobiography and you’re in the public library looking up old weather reports.

Which reminds me: last class Janice read us part of an essay on how to write. It was by some American mystery author who says you should never start a story with the weather. What a crock. In Calgary we never start anything without the weather. Even Meggie and I talk about the weather, and we haven’t been outside since the Labour Day blizzard. Meggie says it was just a brush of wet snow, but it looked like a blizzard to me. And, in my memoirs, I get to call the meteorological shots. Not that these are my actual memoirs. They’re just part of the assignment Janice set for us this week. We are to write the first thing that comes into our heads and keep on writing until we’ve filled at least five pages of our notebooks. We’re not to worry about grammar or spelling because this is only an exercise to get us started. It’s supposed to limber up our writing muscles, warm us up so we’re ready to tackle the real thing. Janice says filling five pages should give us the same great feeling that a physical workout gives our flesh and blood muscles. I guess Janice never spent a morning in rehab.

Meggie is done dabbing, so we’re ready to roll. Literally. Meggie pushes my wheelchair, and I call directions because she refuses to hide her eye makeup behind glasses. I won’t say she’s blind as a bat without them, but she could give Mr. Magoo a run for his money. My eyes are fine since I had my cataracts done, so the no-glasses business is okay with me as long as she turns when I tell her and we don’t run into walls. Our arrangement suits Meggie too, because my chair makes a good substitute for her walker, which she hates using, and I mean hates as in loathes and detests. I don’t really understand why she feels like this because from where I’m sitting, a walker looks like a pretty good deal. The prospect of getting out of this chair and being mobile again is what gets me through rehab mornings. I’ve promised myself that I’ll be galloping around here on a walker of my own by Halloween and back home before Christmas.

So off we go. Meggie says we look like something you’d see in a bad stretch at the Stampede parade—an old clown pushing a bag of rags in a wheelie bin.

Time to navigate.

Assignment #2

WHAT WAS THE MOST IMPORTANT DAY OF YOUR LIFE?

that’s our assignment for this week. I suspect your children may never speak to you again if you don’t make it the day they were born or the day you met their father. Meggie says don’t show them what you’ve written. Eventually, when you’re off warbling alto in the feathered choir, you won’t be around to speak to anyway, so why worry? After a few swigs of gin and tonic, I found myself agreeing with her. Give the pair of us a second gin, and we’d have been raring to publish in the Herald and be damned, but it was time for dinner—that’s five o’clock here at Gimpville—so we tottered off to our macaroni and cheese. Well, some of us wheeled off, if you’re going to be a stickler for accuracy.

By the way, this assignment is only another exercise, not our real memoirs. I’m beginning to wonder when we’ll get to those. Someone should tell Janice that around here it doesn’t do to dawdle. I don’t think she understands that if we don’t get down to business soon, some of us may reach The End before our memoirs do. All in all though, I have to admit I only signed up for the class so I’d have something to occupy my mind until I go home. Hang around this place long enough and you realize that “dying of boredom” is not just an expression.

I can see I’m going to have to watch myself. That boredom business sounded pretty negative, didn’t it? I vowed when I had to come to Foothills Sunset that I wouldn’t be a whiner. I fell off a chair and broke a few bits and pieces. Nothing will change that. But if you give in and start to dwell on all the things that get you down, you’ll only make yourself miserable and go gaga quicker. At least that’s what Meggie claims. She’s been here longer than me and says that she’s seen it happen more than once. According to her, it’s whine today and wither away tomorrow. So get well, go home, get on with my life.

That’s the plan. In the meantime, I’ve decided to go all Norman Vincent Peale and think positively.

All right. Time to get organized and buckle down to this Most Important Day stuff.

For me, there’s no thinking required. The most important day of my life was the day I went to work for Mr. Miyashita. Period. It certainly wasn’t something I’d planned on doing. Strange how a decision made on impulse, a morning’s whim really, can have such a profound effect on the rest of your life. I’m such a dithery old thing now that my spur-of-the-moment choice to take the job seems nothing short of miraculous. But on that winter morning all those years ago, it was simply a case of boredom meets opportunity. And what an opportunity! My time with Mr. Miyashita opened a new world to me, a world I could not have imagined before I met him. Thanks to him, I got an education, one that instilled in me an intellectual curiosity that I like to think has not diminished over the years. He also sent me on the greatest adventure of my life, a trip to Hong Kong on the Pan American flying boat in the fall of 1941. That journey changed my life, although if I’m to be honest, I’d have to admit not all the changes were happy ones. Still, it was an adventure on a grand scale, and I got to live it. How many people can say that?

Compared to my days at Miyashita Industries, I suppose the rest of my life has been pretty ordinary. Not that it’s been an unhappy life. Far from it. On the whole, I’d say I’ve had more than my share of happiness—or at least as much as anyone with a brain and a conscience can reasonably expect. But no one who has been around as long as I have can escape at least a small helping of the misery that the world has on constant offer, especially those of us who lived through the war. Believe me, in the months following my trip to Hong Kong, sometimes my helping didn’t feel all that small. The morning I stood and watched a train take the Miyashitas away to the New Denver camp was the morning I learned what it means to be sick at heart.

There I go, rambling all over the place again. One thing I know with absolute certainty is that the ability to concentrate definitely diminishes with age. At least it has in my case. I can see that from now on I’m going to have to do my best to collect my thoughts and begin at the beginning if I want the rest of this assignment to make any sense.

I turned nineteen in February of 1939. I still lived at home with my parents and my brother Charlie who was two years younger than me. I’d been working as a typist at the Greer & Western Coal Company for a little over five months. Greer & Western is long gone, but back then it was a thriving concern and our department was kept very busy. Still, typing is typing, and my days had become so routine that those five months felt more like five years. Every morning Mum packed me a paper bag lunch, and every morning I’d catch the streetcar from east Calgary to Greer & Western’s downtown office. There, every morning on the dot of eight-thirty, I’d sit down at a desk in a room with three other girls, lift the cover off my Underwood and go to work. I’d type until lunch, then after lunch I’d type some more. At five-thirty I’d cover my machine and catch the street car home. Same thing day in day out, except on Saturdays when the office closed at noon. It was about as exciting as our days here at Foothills Sunset. But you have to keep in mind that this was at the end of the Great Depression when you were lucky to have a job at all, as my dad was so fond of telling me. Especially if you were a woman. He always added that.

Most of my time at Greer & Western is now a blur of indistinguishable days, except for the Thursday I got the job with Mr. Miyashita. I’ll say this for Janice, until I began to work on her assignment, I had no idea that even its smallest details had stayed with me all these years. Startling to be caught unaware by your own memory, ambushed by colours and smells and sounds rushing in all of a tumble, from God knows where. Made me feel a bit shaky at first to discover that whole day still rattling around in my old brain.

When I said goodbye to Mum that morning, the mercury in the thermometer outside our kitchen window huddled down near the forty below mark. With every drop of moisture frozen from it, the air was so dry that little snaps of static electricity sparked off everything I touched. I even got a shock from Mum when she kissed me goodbye. It was only two blocks from our house to the streetcar stop, but it always felt farther when I was wearing my winter gear. That morning, I’d piled on an extra sweater, my heavy overcoat, two pairs of mittens, wool stockings and felt-lined boots. A wool toque pulled down over my ears and a big scarf pulled up over my nose completed the ensemble. God, what a lot of effort it took to go out in the cold back then. If you ask me, down-filled wind-proofs, all warm air and no substance, are one of the wonders of the modern world, and Thinsulate is a preview of heaven. I only had to wait for the streetcar a minute or two, but by the time it trundled up to our stop my fingers ached and my toes had begun to numb. A gust of air stirred up by the slowing car made my eyes water. Tears trickled down my cheeks and froze the instant they hit the scarf.

The ride from our house to downtown took fifteen minutes. That morning, frost on the overhead wires made the trolleys a little temperamental, but we still pulled up to my stop by The Hudson’s Bay at eight twenty, right on time. Greer & Western Coal occupied the top two floors of a brick building on 9th Avenue across the street from the Palliser Hotel, so ten minutes left ample time to walk there and get settled at my desk.

Despite the bitter cold, it was a relief when the driver opened the doors and I stepped out into fresh air, away from the fug of cigarette smoke, old sweat and wet wool that hung in the crowded cars on bitter days. Sometimes, depending on where you sat, you got whiffs of the coal fire in the driver’s little heater, and in the evening, the reek of fish and chips in their greasy wrappings, riding home for someone’s supper. Those fifteen minutes between home and downtown with all the windows shut could leave you feeling pretty queasy, especially if some man at the back in the smoking compartment lit a cigar. Matter of fact, just sitting here thinking about it is enough to make my stomach churn. Or maybe what’s really upsetting me is having to admit that I remember a morning all those years ago more vividly than any morning last week. That is one of the classic signs of old age, and it’s supposed to happen to other people, not to me.

I see me at my desk in a room with high ceilings and three tall sash windows. I hear the clatter of typewriters punctuated by the bangs and hisses of reluctant pipes as steam blasts through them on its way to the radiators. Again the smells. This time it’s clouds of Evening in Paris wafting off to battle the powerful forces of Raleigh’s Medicated Ointment and Life Buoy soap. The lower panes of the windows glitter with frost ferns while the upper glass remains clear and the morning sun shafts through, turning dust motes to floating specks of light and warming my shoulders as I type a letter to the transportation manager of the Portland Distributing Company on the subject of the proposed delivery date for a shipment of Drumheller bituminous.

The four of us had been at work for an hour. I had just put a new sheet of carbon paper between Greer & Western’s best linen bond and the cheap stuff we used for copies, when the big boss, Mr. Calthorpe himself, appeared at the typing room door. Everyone stopped working and looked up as he creaked across the oiled hardwood to the front of the room, followed by Miss Bayliss, the Simona Legree of the typing pool.

“Girls! Your attention!” Miss Bayliss ordered in her clipped and chilly tones. Since this was the first time Greer & Western’s president had ever set foot in the typing room, we knew it must be something important.

“Good morning girls,” Mr. Calthorpe began. His smile was genial if a trifle strained. “I’ve come to ask a favour of you. A friend of Greer & Western’s is in difficulty, and I’m hoping one of you young ladies will be able to help us help him.” He paused for effect, letting us prepare for the enormity of what he was about to say.

“As you may already know, Mr. Hero Miyashita is the head of the Canadian branch of Miyashita Industries. His private secretary was taken ill a few weeks ago and has had to return home to Japan. Until the company can arrange for a new man to be sent from their headquarters in Hiroshima, Mr. Miyashita is in need of some crackerjack secretarial help. That’s why I’m here today. I have come to ask one of you charming and talented young ladies to volunteer to work for Miyashita Industries. Of course, it would be a temporary arrangement, a few months’ secondment to tide Mr. Miyashita over until his new permanent secretary arrives.”