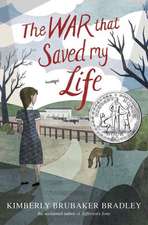

For Freedom: The Story of a French Spy

Autor Kimberly Brubaker Bradleyen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2004 – vârsta de la 12 ani

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Young Hoosier Book Award (2008)

Suzanne David's everyday life is suddenly shattered in 1940 when a bomb drops on the main square of her hometown, the city of Cherbourg, France, killing a pregnant neighbor right in front of her. Until then the war had seemed far away, not something that would touch her or her teenage friends. Now Suzanne's family is kicked out onto the street as German soldiers take over their house as a barracks.

Suzanne clings to the one thing she really loves--singing. Her voice is so amazing that she is training to become an opera singer. As Suzanne travels around for rehearsals, cosume fittings, or lessons, she learns more about what the Nazis are doing and about the people who are "disappearing." Her travels are noticed by someone else, an organizer of the French Resistance. Soon Suzanne is a secret courier, a spy fighting for France and risking her own life for freedom.

From the Hardcover edition.

Preț: 47.20 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 71

Preț estimativ în valută:

9.03€ • 9.82$ • 7.59£

9.03€ • 9.82$ • 7.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780440418313

ISBN-10: 0440418313

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 111 x 176 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Editura: Laurel Leaf Library

Locul publicării:New York, NY

ISBN-10: 0440418313

Pagini: 192

Dimensiuni: 111 x 176 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.1 kg

Editura: Laurel Leaf Library

Locul publicării:New York, NY

Extras

Chapter One

For me the war began on May 29, 1940. I was thirteen years old.

It was a Wednesday, the day we studied catechism and had choir practice and then had the afternoon free. Of course, I had to remain after choir to rehearse my solo, but when that was finished I found my friend Yvette. Together we went to Soeur Margritte.

“S’il vous plaît, please, Soeur Margritte, may we go down to the beach?” we asked.

Our convent school was high among the hills of Cherbourg; school was farther from the beach than my own home. But while we were not permitted home except on weekends, we were sometimes permitted to go about town. Yvette and I were good students, well behaved. Always follow the rules, my papa told me, and you will be all right. I always did, and I always was.

“We will take our homework,” Yvette said.

“It’s such a beautiful day,” I said.

“We will be back before supper,” we chorused.

France had been at war with Germany for nearly six months, yet there had been so little fighting that it seemed to mean nothing. The German army had spread across Europe, almost unopposed; neither the French nor the British had done much to stop them. There were English soldiers stationed in Cherbourg—I saw them when Maman and I went to the market on Saturdays—but they were quiet and polite and never bothered anyone. I couldn’t imagine them actually fighting. Some days it was hard to believe we were in a real war.

Which is not to say we weren’t paying attention. We listened to the radio and read the newspaper reports with increasing dread. We knew Hitler was coming; we feared that nothing could stop him. Papa and Maman talked in low voices at the dinner table, and sometimes Papa pounded his fist on the table and swore. “That Hitler!” he would say. “That cursed son of Satan!”

But I was only thirteen. My brothers, Pierre and Etienne, were fourteen and sixteen, too young to be soldiers; Etienne was lame as well. And I was studying to be a famous opera singer. I loved singing like nothing else. At Christmas I had sung a solo in the church choir, Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” and our director had said I was talented and should pursue a career. So now I had a music tutor, Madame Marcelle; I took special voice lessons twice a week and practiced hard every day.

So it was not that I was not paying attention to the war, but that I never thought the war could hurt me.

“Yes,” Soeur Margritte decided. She was the nicest of the sisters. “It’s a beautiful day, and who knows how many carefree days we have left. You may go. Have a nice time—but do your homework!”

We skipped down the cobblestone streets. The wind blowing in from the Channel tousled our skirts, pulled at our hair. I sang an aria from Carmen as we drew closer. Carmen was my favorite opera. I knew most of the part of Carmen, but I still could not reach some of the high notes.

“Oh, tais-toi,” said Yvette, rolling her eyes at me. “Be quiet. Singing, always singing. I bet you sing in your sleep.”

I probably did sing in my sleep. Someday I would sing in Paris. I dreamed of it all the time. “I’ll ask Odette,” I said. Odette was one of my roommates. I hummed a few notes, then began again. “Ah! je t’aime, Escamillo, je t’aime, et que je meure si j’ai jamais aimé quelqu’un autant que toi! Ah, I love you, Escamillo, I love you, and may I die if I have ever loved anyone as much as you!”

Yvette grinned. “What a horrible song!” She tossed her hair over her shoulder, flung her arm out dramatically, and began to sing, “Savez-vous planter les choux? Do you know how to plant cabbages?” A simple nursery song. Her voice wobbled, up, down, down, up.

Singing is a talent. You have it or you don’t.

“Come on!” I said, running toward the sea.

We went to the Place Napoléon, the big square near the Gare Maritime, the station where trains could pull right up to the harbor to load and unload the ships. The Church of La Trinité formed part of the square, and from the benches around the edge we could watch the ships in the harbor, the waves curling, and the birds wheeling overhead. People strolled back and forth across the square.

We settled onto a bench in the sun. I opened my history book. History was my favorite subject. Yvette sniffed the air as though it were a flower. “It’s so nice to be outside,” she said, “after being stuck in that stuffy school all day. You’re not going to start with the books already, are you? Let’s talk.”

“Okay.” I closed my book and looked around. “The harbor’s empty. That’s odd.” Cherbourg had an important harbor; before the war big ships had come often. I had been on the Queen Elizabeth once, when she was docked at Cherbourg.

Yvette looked too. “Not really,” she said. “It’s such a pretty day. If I had a boat, I’d take it out today too.”

“Bonjour, Yvette,” came a woman’s pleasant voice. “Bonjour, Suzanne.”

“Bonjour, madame,” we said. Our friend Madame Montagne waved to us as she came nearer. Her little son, Simon, skipped down to the water’s edge and threw rocks into the waves. The Montagnes lived near Yvette’s family, and Madame Montagne was Yvette’s mother’s friend. Since I was Yvette’s best friend, I had known Madame Montagne for years.

“Where’s Marie?” I asked. Marie was her daughter, two years old, a beautiful child with wide blue eyes.

“With her grandmother,” Madame Montagne said. She patted her bulging belly happily. She was going to have a baby very soon; we often talked to her about it. Yvette was knitting her a pair of tiny booties. “I have grown too fat and I can’t carry her this far. But Simon wanted to walk down to the beach. It’s such a pretty day.” She looked up. “Is that a plane?”

There was a far-off buzzing noise. It did sound like a plane.

“Salut, Simon!” Yvette yelled. Simon waved to her.

I hummed a scale to myself, D minor, as I found my place in my history book again.

The buzzing noise grew louder.

“Simon!” called Madame Montagne. “Do not get your shoes wet! Stay out of the water!” She started to walk toward him.

Suddenly the noise turned into a roar. Planes swarmed overhead, many of them, their engines fast and loud.

I jumped to my feet. My books slid to the ground. Yvette turned toward me, her eyes wide. She said something I didn’t hear.

The beach, the square, exploded.

From the Hardcover edition.

For me the war began on May 29, 1940. I was thirteen years old.

It was a Wednesday, the day we studied catechism and had choir practice and then had the afternoon free. Of course, I had to remain after choir to rehearse my solo, but when that was finished I found my friend Yvette. Together we went to Soeur Margritte.

“S’il vous plaît, please, Soeur Margritte, may we go down to the beach?” we asked.

Our convent school was high among the hills of Cherbourg; school was farther from the beach than my own home. But while we were not permitted home except on weekends, we were sometimes permitted to go about town. Yvette and I were good students, well behaved. Always follow the rules, my papa told me, and you will be all right. I always did, and I always was.

“We will take our homework,” Yvette said.

“It’s such a beautiful day,” I said.

“We will be back before supper,” we chorused.

France had been at war with Germany for nearly six months, yet there had been so little fighting that it seemed to mean nothing. The German army had spread across Europe, almost unopposed; neither the French nor the British had done much to stop them. There were English soldiers stationed in Cherbourg—I saw them when Maman and I went to the market on Saturdays—but they were quiet and polite and never bothered anyone. I couldn’t imagine them actually fighting. Some days it was hard to believe we were in a real war.

Which is not to say we weren’t paying attention. We listened to the radio and read the newspaper reports with increasing dread. We knew Hitler was coming; we feared that nothing could stop him. Papa and Maman talked in low voices at the dinner table, and sometimes Papa pounded his fist on the table and swore. “That Hitler!” he would say. “That cursed son of Satan!”

But I was only thirteen. My brothers, Pierre and Etienne, were fourteen and sixteen, too young to be soldiers; Etienne was lame as well. And I was studying to be a famous opera singer. I loved singing like nothing else. At Christmas I had sung a solo in the church choir, Gounod’s “Ave Maria,” and our director had said I was talented and should pursue a career. So now I had a music tutor, Madame Marcelle; I took special voice lessons twice a week and practiced hard every day.

So it was not that I was not paying attention to the war, but that I never thought the war could hurt me.

“Yes,” Soeur Margritte decided. She was the nicest of the sisters. “It’s a beautiful day, and who knows how many carefree days we have left. You may go. Have a nice time—but do your homework!”

We skipped down the cobblestone streets. The wind blowing in from the Channel tousled our skirts, pulled at our hair. I sang an aria from Carmen as we drew closer. Carmen was my favorite opera. I knew most of the part of Carmen, but I still could not reach some of the high notes.

“Oh, tais-toi,” said Yvette, rolling her eyes at me. “Be quiet. Singing, always singing. I bet you sing in your sleep.”

I probably did sing in my sleep. Someday I would sing in Paris. I dreamed of it all the time. “I’ll ask Odette,” I said. Odette was one of my roommates. I hummed a few notes, then began again. “Ah! je t’aime, Escamillo, je t’aime, et que je meure si j’ai jamais aimé quelqu’un autant que toi! Ah, I love you, Escamillo, I love you, and may I die if I have ever loved anyone as much as you!”

Yvette grinned. “What a horrible song!” She tossed her hair over her shoulder, flung her arm out dramatically, and began to sing, “Savez-vous planter les choux? Do you know how to plant cabbages?” A simple nursery song. Her voice wobbled, up, down, down, up.

Singing is a talent. You have it or you don’t.

“Come on!” I said, running toward the sea.

We went to the Place Napoléon, the big square near the Gare Maritime, the station where trains could pull right up to the harbor to load and unload the ships. The Church of La Trinité formed part of the square, and from the benches around the edge we could watch the ships in the harbor, the waves curling, and the birds wheeling overhead. People strolled back and forth across the square.

We settled onto a bench in the sun. I opened my history book. History was my favorite subject. Yvette sniffed the air as though it were a flower. “It’s so nice to be outside,” she said, “after being stuck in that stuffy school all day. You’re not going to start with the books already, are you? Let’s talk.”

“Okay.” I closed my book and looked around. “The harbor’s empty. That’s odd.” Cherbourg had an important harbor; before the war big ships had come often. I had been on the Queen Elizabeth once, when she was docked at Cherbourg.

Yvette looked too. “Not really,” she said. “It’s such a pretty day. If I had a boat, I’d take it out today too.”

“Bonjour, Yvette,” came a woman’s pleasant voice. “Bonjour, Suzanne.”

“Bonjour, madame,” we said. Our friend Madame Montagne waved to us as she came nearer. Her little son, Simon, skipped down to the water’s edge and threw rocks into the waves. The Montagnes lived near Yvette’s family, and Madame Montagne was Yvette’s mother’s friend. Since I was Yvette’s best friend, I had known Madame Montagne for years.

“Where’s Marie?” I asked. Marie was her daughter, two years old, a beautiful child with wide blue eyes.

“With her grandmother,” Madame Montagne said. She patted her bulging belly happily. She was going to have a baby very soon; we often talked to her about it. Yvette was knitting her a pair of tiny booties. “I have grown too fat and I can’t carry her this far. But Simon wanted to walk down to the beach. It’s such a pretty day.” She looked up. “Is that a plane?”

There was a far-off buzzing noise. It did sound like a plane.

“Salut, Simon!” Yvette yelled. Simon waved to her.

I hummed a scale to myself, D minor, as I found my place in my history book again.

The buzzing noise grew louder.

“Simon!” called Madame Montagne. “Do not get your shoes wet! Stay out of the water!” She started to walk toward him.

Suddenly the noise turned into a roar. Planes swarmed overhead, many of them, their engines fast and loud.

I jumped to my feet. My books slid to the ground. Yvette turned toward me, her eyes wide. She said something I didn’t hear.

The beach, the square, exploded.

From the Hardcover edition.

Notă biografică

Kimberly Brubaker Bradley

Premii

- Young Hoosier Book Award Nominee, 2008