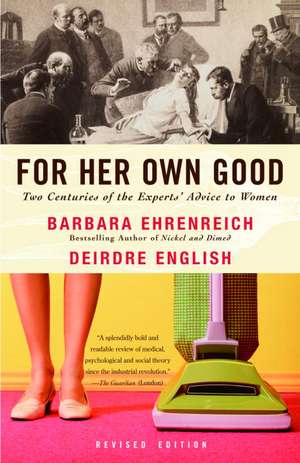

For Her Own Good: Two Centuries of the Experts Advice to Women

Autor Barbara Ehrenreich, Deirdre Englishen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2004

Preț: 84.69 lei

Preț vechi: 101.29 lei

-16% Nou

Puncte Express: 127

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.21€ • 16.82$ • 13.51£

16.21€ • 16.82$ • 13.51£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 03-10 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400078004

ISBN-10: 1400078008

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

ISBN-10: 1400078008

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 134 x 204 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:Anchor Books.

Editura: Anchor Books

Cuprins

Foreword (2004)

ONE In the Ruins of Patriarchy

The Woman Question • The New Masculinism • Feminist and Domestic Solutions • Science and the Triumph of Domesticity

THE RISE OF THE EXPERTS

TWO Witches, Healers, and Gentleman Doctors

The Witch Hunts • The Conflict over Healing Comes to America • Healing as a Commodity • The Popular Health Movement • Lady Doctors Join the Competition

THREE Science and the Ascent of the Experts

The Moral Salvation of Medicine • The Laboratory Mystique • Medicine and the Big Money • Exorcising the Midwives

THE REIGN OF THE EXPERTS

FOUR The Sexual Politics of Sickness

A Mysterious Epidemic • Marriage: The Sexual-Economic Relation • Femininity as a Disease • Men Evolve, Women Devolve • The Dictatorship of the Ovaries • The Uterus vs. the Brain • The Rest Cure • Subverting the Sick Role: Hysteria

FIVE Microbes and the Manufacture of Housework

The Domestic Void • The Romance of the Home • Domestic Scientists Put the House in Order • The Crusade Against Germs • The Manufacture of New Tasks • Feminism Embraces Domestic Science • “Right Living” in the Slums • Domesticity Without the Science

SIX The Century of the Child

Discovery of the Child • The “Child Question” and the Woman Question • The Mothers’ Movement • The Experts Move In

SEVEN Motherhood as Pathology

The Expert Allies with the Child • The Doctors Demand Permissiveness • Libidinal Motherhood • Bad Mothers • “Momism” and the Crisis in American Masculinity • The Obligatory Oedipus Complex • Communism and the Crisis of Overpermissiveness

THE FALL OF THE EXPERTS

EIGHT From Masochistic Motherhood to the Sexual Marketplace

Mid-century Masochism • Gynecology as Psychotherapy • Revolt of the Masochistic Mom • The Rise of the Single Girl • Spread of the Singles Culture • Popular Psychology and the Single Lifestyle

Afterword: The End of the Romance (2004)

Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

ONE In the Ruins of Patriarchy

The Woman Question • The New Masculinism • Feminist and Domestic Solutions • Science and the Triumph of Domesticity

THE RISE OF THE EXPERTS

TWO Witches, Healers, and Gentleman Doctors

The Witch Hunts • The Conflict over Healing Comes to America • Healing as a Commodity • The Popular Health Movement • Lady Doctors Join the Competition

THREE Science and the Ascent of the Experts

The Moral Salvation of Medicine • The Laboratory Mystique • Medicine and the Big Money • Exorcising the Midwives

THE REIGN OF THE EXPERTS

FOUR The Sexual Politics of Sickness

A Mysterious Epidemic • Marriage: The Sexual-Economic Relation • Femininity as a Disease • Men Evolve, Women Devolve • The Dictatorship of the Ovaries • The Uterus vs. the Brain • The Rest Cure • Subverting the Sick Role: Hysteria

FIVE Microbes and the Manufacture of Housework

The Domestic Void • The Romance of the Home • Domestic Scientists Put the House in Order • The Crusade Against Germs • The Manufacture of New Tasks • Feminism Embraces Domestic Science • “Right Living” in the Slums • Domesticity Without the Science

SIX The Century of the Child

Discovery of the Child • The “Child Question” and the Woman Question • The Mothers’ Movement • The Experts Move In

SEVEN Motherhood as Pathology

The Expert Allies with the Child • The Doctors Demand Permissiveness • Libidinal Motherhood • Bad Mothers • “Momism” and the Crisis in American Masculinity • The Obligatory Oedipus Complex • Communism and the Crisis of Overpermissiveness

THE FALL OF THE EXPERTS

EIGHT From Masochistic Motherhood to the Sexual Marketplace

Mid-century Masochism • Gynecology as Psychotherapy • Revolt of the Masochistic Mom • The Rise of the Single Girl • Spread of the Singles Culture • Popular Psychology and the Single Lifestyle

Afterword: The End of the Romance (2004)

Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

Extras

One

In the Ruins of Patriarchy

"If you would get up and do something you would feel better," said my mother. I rose drearily, and essayed to brush up the floor a little, with a dustpan and small whiskbroom, but soon dropped those implements exhausted, and wept again in helpless shame.

I, the ceaselessly industrious, could do no work of any kind. I was so weak that the knife and fork sank from my hands-too tired to eat. I could not read nor write nor paint nor sew nor talk nor listen to talking, nor anything. I lay on the lounge and wept all day. The tears ran down into my ears on either side. I went to bed crying, woke in the night crying, sat on the edge of the bed in the morning and cried-from sheer continuous pain. Not physical, the doctors examined me and found nothing the matter.1

It was 1885 and Charlotte Perkins Stetson had just given birth to a daughter, Katherine. "Of all angelic babies that darling was the best, a heavenly baby." And yet young Mrs. Stetson wept and wept, and when she nursed her baby "the tears ran down on my breast. . . ."

The doctors told her she had "nervous prostration." To her it felt like "a sort of gray fog [had] drifted across my mind, a cloud that grew and darkened." The fog never entirely lifted from the life of Charlotte Perkins Stetson (later Gilman). Years later, in the midst of an active career as a feminist writer and lecturer, she would find herself overcome by the same lassitude, incapable of making the smallest decision, mentally numb.

Paralysis struck Charlotte Perkins Gilman when she was only twenty-five years old, energetic and intelligent, a woman who seemed to have her life open before her. It hit young Jane Addams-the famous social reformer-at the same time of life. Addams was affluent, well-educated for a girl, ambitious to study medicine. Then, in 1881, at the age of twenty-one, she fell into a "nervous depression" which paralyzed her for seven years and haunted her long after she began her work at Hull-House in the Chicago slums. She was gripped by "a sense of futility, of misdirected energy" and was conscious of her estrangement from "the active, emotional life" within the family which had automatically embraced earlier generations of women. "It was doubtless true," she later wrote "that I was

'Weary of myself and sick of asking

What I am and what I ought to be.'"

Margaret Sanger-the birth control crusader-was another case. She was twenty years old, happily married, and, physically at least, seemed to be making a good recovery from tuberculosis. Suddenly she stopped getting out of bed, refused to talk. In the outside world, Theodore Roosevelt was running for President on the theme of the "strenuous life." But when relatives asked Margaret Sanger what she would like to do, she could only say, "Nothing." "Where would you like to go?" they persisted: "Nowhere."

Ellen Swallow (later Ellen Richards-founder of the early-twentieth-century domestic science movement) succumbed when she was twenty-four. She was an energetic, even compulsive, young woman; and, like Addams, felt estranged from the intensely domestic life her mother had led. Returning home from a brief period of independence, she found herself almost too weak to do household chores. "Lay down sick . . ." she entered in her diary, "Oh so tired . . ." and on another day, "Wretched," and again, "tired."

It was as if they had come to the brink of adult life and then refused to go on. They stopped in their tracks, paralyzed. The problem wasn't a lack of things to do. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, like Jane Addams, felt "intense shame" that she was not up and about. All of them had family responsibilities to meet; all but Jane Addams had houses to run. They were women with other interests too-science, or art, or philosophy-and all of them were passionately idealistic. And yet, for a while, they could not go on.

For, in the new world of the nineteenth century, what was a woman to do? Did she build a life, like her aunts and her mother, in the warmth of the family-or did she throw herself into the nervous activism of a world which was already presuming to call itself "modern"? Either way, wouldn't she be ridiculous, a kind of misfit? Certainly out of place if she tried to fit into the "men's world" of business, politics, science. But in a historical sense, perhaps even more out of place if she remained in the home, isolated from the grand march of industry and progress. "She was intelligent and generous"; Henry James wrote of the heroine in Portrait of a Lady, "it was a fine free nature; but what was she going to do with herself?"

Certainly the question had been asked before Charlotte Perkins Gilman's and Jane Addams's generation, and certainly other women had collapsed because they did not have the answers. But only in the last one hundred years or so in the Western world does this private dilemma surface as a gripping public issue-the Woman Question or "the woman problem." The misery of a Charlotte Gilman or Jane Addams, the crippling indecisiveness, is amplified in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries among tens of thousands of women. A minority transform their numbness into anger and become activists in reform movements; many-the ones whose names we don't know-remained permanently depressed, bewildered, sick.

Men, men of the "establishment"-physicians, philosophers, scientists-addressed themselves to the Woman Question in a constant stream of books and articles. For while women were discovering new questions and doubts, men were discovering that women were themselves a question, an anomaly when viewed from the busy world of industry. They couldn't be included in the men's world, yet they no longer seemed to fit in their traditional place. "Have you any notion how many books are written about women in the course of one year?" Virginia Woolf asked an audience of women. "Have you any notion how many are written by men? Are you aware that you are, perhaps, the most discussed animal in the universe?" From a masculine point of view the Woman Question was a problem of control: Woman had become an issue, a social problem-something to be investigated, analyzed, and solved.

This book is about the scientific answer to the Woman Question, as elaborated over the last hundred years by a new class of experts-physicians, psychologists, domestic scientists, child-raising experts. These men-and, more rarely, women-presented themselves as authorities on the painful dilemma confronted by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Jane Addams, and so many others: What is woman's true nature? And what, in an industrial world which no longer honored women's traditional skills, was she to do? Physicians were the first of the new experts. With claims to knowledge encompassing all of human biological existence, they were the first to pass judgment on the social consequences of female anatomy and to prescribe the "natural" life plan for women. They were followed by a horde of more specialized experts, each group claiming dominion over some area of women's lives, and all claiming that their authority flowed directly from biological science. In the first part of this book we will trace the rise of the psychomedical experts, focusing on medicine as a paradigm of professional authority. In the second part of the book we will see how the experts used their authority to define women's domestic activities down to the smallest details of housework and child raising. With each subject area we will move ahead in time until we reach the present and the period of the decline of the experts-our own time, when the Woman Question has at last been reopened for new answers.

The relationship between women and the experts was not unlike conventional relationships between women and men. The experts wooed their female constituency, promising the "right" and scientific way to live, and women responded-most eagerly in the upper and middle classes, more slowly among the poor-with dependency and trust. It was never an equal relationship, for the experts' authority rested on the denial or destruction of women's autonomous sources of knowledge: the old networks of skill-sharing, the accumulated lore of generations of mothers. But it was a relationship that lasted right up to our own time, when women began to discover that the experts' answer to the Woman Question was not science after all, but only the ideology of a masculinist society, dressed up as objective truth. The reason why women would seek the "scientific" answer in the first place and the reason why that answer would betray them in the end are locked together in history. In the section which follows we go back to the origins of the Woman Question, when science was a fresh and liberating force, when women began to push out into the unknown world, and the romance between women and the experts began.

The Woman Question

The Woman Question arose in the course of a historic transformation whose scale later generations have still barely grasped. It was the "industrial revolution," and even "revolution" is too pallid a word. From the Scottish highlands to the Appalachian hills, from the Rhineland to the Mississippi Valley, whole villages were emptied to feed the factory system with human labor. People were wrested from the land suddenly, by force; or more subtly, by the pressure of hunger and debt-uprooted from the ancient security of family, clan, parish. A settled, agrarian life which had persisted more or less for centuries was destroyed in one tenth the time it had taken for the Roman Empire to fall, and the old ways of thinking, the old myths and old rules, began to lift like the morning fog.

Marx and Engels-usually thought of as the instigators of disorder rather than the chroniclers of it-were the first to grasp the cataclysmic nature of these changes. An old world was dying and a new one was being born:

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life and his relations with his kind.2

Incredible, once unthinkable, possibilities opened up as all the "fixed, fast-frozen relations"-between man and woman, between parents and children, between the rich and the poor-were thrown into question. Over one hundred and fifty years later, the dust has still not settled.

On the far side of the industrial revolution is what we will call, for our purposes, the Old Order. Historians will mark off many "eras" within these centuries of agrarian life: royal lines, national boundaries, military technology, fashions, art and architecture-all evolve and change throughout the Old Order. History is made: there are conquests, explorations, new lines of trade. Nevertheless, for all the visible drama of history, the lives of ordinary people, doing ordinary things, change very little-and that only slowly.

Routine predominates at the level of everyday life: corn is sown as it was always sown, maize planted, rice fields levelled, ships sail the Red Sea as they have always sailed it.3

Only here, at the level of everyday life, do we find the patterns that make this an "order." If these patterns are monotonous and repetitive compared to the spectacle of conventional history-with its brilliant personalities, military adventures and court intrigues-that is because these patterns are shaped by natural events which are also monotonous and repetitive-seasons, plantings, the cycle of human reproduction.

Three patterns of social life in the Old Order stand out and give it consistency: the Old Order is unitary. There is of course always a minority of people whose lives-acted out on a plane above dull necessity and the routines of labor-are complex and surprising. But life, for the great majority of people, has a unity and simplicity which will never cease to fascinate the "industrial man" who comes later. This life is not marked off into different "spheres" or "realms" of experience: "work" and "home," "public" and "private," "sacred" and "secular." Production (of food, clothing, tools) takes place in the same rooms or outdoor spaces where children grow up, babies are born, couples come together. The family relation is not secluded in the realm of emotion; it is a working relation. Biological life-sexual desire, childbirth, sickness, the progressive infirmity of age-impinges directly on the group activities of production and play. Ritual and superstition affirm the unity of body and earth, biology and labor: menstruating women must not bake bread; conception is most favored at the time of the spring planting; sexual transgressions will bring blight and ruin to the crops; and so on.

The human relations of family and village, knit by common labor as well as sex and affection, are paramount. There is not yet an external "economy" connecting the fortunes of the peasant with the decisions of a merchant in a remote city. If people go hungry, it is not because the price of their crops fell, but because the rain did not. There are marketplaces, but there is not yet a market to dictate the opportunities and activities of ordinary people.

The Old Order is patriarchal: authority over the family is vested in the elder males, or male. He, the father, makes the decisions which control the family's work, purchases, marriages. Under the rule of the father, women have no complex choices to make, no questions as to their nature or destiny: the rule is simply obedience. An early-nineteenth-century American minister counseled brides:

Bear always in mind your true situation and have the words of the apostle perpetually engraven on your heart. Your duty is submission-"Submission and obedience are the lessons of your life and peace and happiness will be your reward." Your husband is, by the laws of God and of man, your superior; do not ever give him cause to remind you of it.4

The patriarchal order of the household is magnified in the governance of village, church, nation. At home was the father, in church was the priest or minister, at the top were the "town fathers," the local nobility, or, as they put it in Puritan society, "the nursing fathers of the Commonwealth," and above all was "God the Father."

Thus the patriarchy of the Old Order was reinforced at every level of social organization and belief. For women, it was total, inescapable. Rebellious women might be beaten privately (with official approval) or punished publicly by the village "fathers," and any woman who tried to survive on her own would be at the mercy of random male violence.

In the Ruins of Patriarchy

"If you would get up and do something you would feel better," said my mother. I rose drearily, and essayed to brush up the floor a little, with a dustpan and small whiskbroom, but soon dropped those implements exhausted, and wept again in helpless shame.

I, the ceaselessly industrious, could do no work of any kind. I was so weak that the knife and fork sank from my hands-too tired to eat. I could not read nor write nor paint nor sew nor talk nor listen to talking, nor anything. I lay on the lounge and wept all day. The tears ran down into my ears on either side. I went to bed crying, woke in the night crying, sat on the edge of the bed in the morning and cried-from sheer continuous pain. Not physical, the doctors examined me and found nothing the matter.1

It was 1885 and Charlotte Perkins Stetson had just given birth to a daughter, Katherine. "Of all angelic babies that darling was the best, a heavenly baby." And yet young Mrs. Stetson wept and wept, and when she nursed her baby "the tears ran down on my breast. . . ."

The doctors told her she had "nervous prostration." To her it felt like "a sort of gray fog [had] drifted across my mind, a cloud that grew and darkened." The fog never entirely lifted from the life of Charlotte Perkins Stetson (later Gilman). Years later, in the midst of an active career as a feminist writer and lecturer, she would find herself overcome by the same lassitude, incapable of making the smallest decision, mentally numb.

Paralysis struck Charlotte Perkins Gilman when she was only twenty-five years old, energetic and intelligent, a woman who seemed to have her life open before her. It hit young Jane Addams-the famous social reformer-at the same time of life. Addams was affluent, well-educated for a girl, ambitious to study medicine. Then, in 1881, at the age of twenty-one, she fell into a "nervous depression" which paralyzed her for seven years and haunted her long after she began her work at Hull-House in the Chicago slums. She was gripped by "a sense of futility, of misdirected energy" and was conscious of her estrangement from "the active, emotional life" within the family which had automatically embraced earlier generations of women. "It was doubtless true," she later wrote "that I was

'Weary of myself and sick of asking

What I am and what I ought to be.'"

Margaret Sanger-the birth control crusader-was another case. She was twenty years old, happily married, and, physically at least, seemed to be making a good recovery from tuberculosis. Suddenly she stopped getting out of bed, refused to talk. In the outside world, Theodore Roosevelt was running for President on the theme of the "strenuous life." But when relatives asked Margaret Sanger what she would like to do, she could only say, "Nothing." "Where would you like to go?" they persisted: "Nowhere."

Ellen Swallow (later Ellen Richards-founder of the early-twentieth-century domestic science movement) succumbed when she was twenty-four. She was an energetic, even compulsive, young woman; and, like Addams, felt estranged from the intensely domestic life her mother had led. Returning home from a brief period of independence, she found herself almost too weak to do household chores. "Lay down sick . . ." she entered in her diary, "Oh so tired . . ." and on another day, "Wretched," and again, "tired."

It was as if they had come to the brink of adult life and then refused to go on. They stopped in their tracks, paralyzed. The problem wasn't a lack of things to do. Charlotte Perkins Gilman, like Jane Addams, felt "intense shame" that she was not up and about. All of them had family responsibilities to meet; all but Jane Addams had houses to run. They were women with other interests too-science, or art, or philosophy-and all of them were passionately idealistic. And yet, for a while, they could not go on.

For, in the new world of the nineteenth century, what was a woman to do? Did she build a life, like her aunts and her mother, in the warmth of the family-or did she throw herself into the nervous activism of a world which was already presuming to call itself "modern"? Either way, wouldn't she be ridiculous, a kind of misfit? Certainly out of place if she tried to fit into the "men's world" of business, politics, science. But in a historical sense, perhaps even more out of place if she remained in the home, isolated from the grand march of industry and progress. "She was intelligent and generous"; Henry James wrote of the heroine in Portrait of a Lady, "it was a fine free nature; but what was she going to do with herself?"

Certainly the question had been asked before Charlotte Perkins Gilman's and Jane Addams's generation, and certainly other women had collapsed because they did not have the answers. But only in the last one hundred years or so in the Western world does this private dilemma surface as a gripping public issue-the Woman Question or "the woman problem." The misery of a Charlotte Gilman or Jane Addams, the crippling indecisiveness, is amplified in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries among tens of thousands of women. A minority transform their numbness into anger and become activists in reform movements; many-the ones whose names we don't know-remained permanently depressed, bewildered, sick.

Men, men of the "establishment"-physicians, philosophers, scientists-addressed themselves to the Woman Question in a constant stream of books and articles. For while women were discovering new questions and doubts, men were discovering that women were themselves a question, an anomaly when viewed from the busy world of industry. They couldn't be included in the men's world, yet they no longer seemed to fit in their traditional place. "Have you any notion how many books are written about women in the course of one year?" Virginia Woolf asked an audience of women. "Have you any notion how many are written by men? Are you aware that you are, perhaps, the most discussed animal in the universe?" From a masculine point of view the Woman Question was a problem of control: Woman had become an issue, a social problem-something to be investigated, analyzed, and solved.

This book is about the scientific answer to the Woman Question, as elaborated over the last hundred years by a new class of experts-physicians, psychologists, domestic scientists, child-raising experts. These men-and, more rarely, women-presented themselves as authorities on the painful dilemma confronted by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Jane Addams, and so many others: What is woman's true nature? And what, in an industrial world which no longer honored women's traditional skills, was she to do? Physicians were the first of the new experts. With claims to knowledge encompassing all of human biological existence, they were the first to pass judgment on the social consequences of female anatomy and to prescribe the "natural" life plan for women. They were followed by a horde of more specialized experts, each group claiming dominion over some area of women's lives, and all claiming that their authority flowed directly from biological science. In the first part of this book we will trace the rise of the psychomedical experts, focusing on medicine as a paradigm of professional authority. In the second part of the book we will see how the experts used their authority to define women's domestic activities down to the smallest details of housework and child raising. With each subject area we will move ahead in time until we reach the present and the period of the decline of the experts-our own time, when the Woman Question has at last been reopened for new answers.

The relationship between women and the experts was not unlike conventional relationships between women and men. The experts wooed their female constituency, promising the "right" and scientific way to live, and women responded-most eagerly in the upper and middle classes, more slowly among the poor-with dependency and trust. It was never an equal relationship, for the experts' authority rested on the denial or destruction of women's autonomous sources of knowledge: the old networks of skill-sharing, the accumulated lore of generations of mothers. But it was a relationship that lasted right up to our own time, when women began to discover that the experts' answer to the Woman Question was not science after all, but only the ideology of a masculinist society, dressed up as objective truth. The reason why women would seek the "scientific" answer in the first place and the reason why that answer would betray them in the end are locked together in history. In the section which follows we go back to the origins of the Woman Question, when science was a fresh and liberating force, when women began to push out into the unknown world, and the romance between women and the experts began.

The Woman Question

The Woman Question arose in the course of a historic transformation whose scale later generations have still barely grasped. It was the "industrial revolution," and even "revolution" is too pallid a word. From the Scottish highlands to the Appalachian hills, from the Rhineland to the Mississippi Valley, whole villages were emptied to feed the factory system with human labor. People were wrested from the land suddenly, by force; or more subtly, by the pressure of hunger and debt-uprooted from the ancient security of family, clan, parish. A settled, agrarian life which had persisted more or less for centuries was destroyed in one tenth the time it had taken for the Roman Empire to fall, and the old ways of thinking, the old myths and old rules, began to lift like the morning fog.

Marx and Engels-usually thought of as the instigators of disorder rather than the chroniclers of it-were the first to grasp the cataclysmic nature of these changes. An old world was dying and a new one was being born:

All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life and his relations with his kind.2

Incredible, once unthinkable, possibilities opened up as all the "fixed, fast-frozen relations"-between man and woman, between parents and children, between the rich and the poor-were thrown into question. Over one hundred and fifty years later, the dust has still not settled.

On the far side of the industrial revolution is what we will call, for our purposes, the Old Order. Historians will mark off many "eras" within these centuries of agrarian life: royal lines, national boundaries, military technology, fashions, art and architecture-all evolve and change throughout the Old Order. History is made: there are conquests, explorations, new lines of trade. Nevertheless, for all the visible drama of history, the lives of ordinary people, doing ordinary things, change very little-and that only slowly.

Routine predominates at the level of everyday life: corn is sown as it was always sown, maize planted, rice fields levelled, ships sail the Red Sea as they have always sailed it.3

Only here, at the level of everyday life, do we find the patterns that make this an "order." If these patterns are monotonous and repetitive compared to the spectacle of conventional history-with its brilliant personalities, military adventures and court intrigues-that is because these patterns are shaped by natural events which are also monotonous and repetitive-seasons, plantings, the cycle of human reproduction.

Three patterns of social life in the Old Order stand out and give it consistency: the Old Order is unitary. There is of course always a minority of people whose lives-acted out on a plane above dull necessity and the routines of labor-are complex and surprising. But life, for the great majority of people, has a unity and simplicity which will never cease to fascinate the "industrial man" who comes later. This life is not marked off into different "spheres" or "realms" of experience: "work" and "home," "public" and "private," "sacred" and "secular." Production (of food, clothing, tools) takes place in the same rooms or outdoor spaces where children grow up, babies are born, couples come together. The family relation is not secluded in the realm of emotion; it is a working relation. Biological life-sexual desire, childbirth, sickness, the progressive infirmity of age-impinges directly on the group activities of production and play. Ritual and superstition affirm the unity of body and earth, biology and labor: menstruating women must not bake bread; conception is most favored at the time of the spring planting; sexual transgressions will bring blight and ruin to the crops; and so on.

The human relations of family and village, knit by common labor as well as sex and affection, are paramount. There is not yet an external "economy" connecting the fortunes of the peasant with the decisions of a merchant in a remote city. If people go hungry, it is not because the price of their crops fell, but because the rain did not. There are marketplaces, but there is not yet a market to dictate the opportunities and activities of ordinary people.

The Old Order is patriarchal: authority over the family is vested in the elder males, or male. He, the father, makes the decisions which control the family's work, purchases, marriages. Under the rule of the father, women have no complex choices to make, no questions as to their nature or destiny: the rule is simply obedience. An early-nineteenth-century American minister counseled brides:

Bear always in mind your true situation and have the words of the apostle perpetually engraven on your heart. Your duty is submission-"Submission and obedience are the lessons of your life and peace and happiness will be your reward." Your husband is, by the laws of God and of man, your superior; do not ever give him cause to remind you of it.4

The patriarchal order of the household is magnified in the governance of village, church, nation. At home was the father, in church was the priest or minister, at the top were the "town fathers," the local nobility, or, as they put it in Puritan society, "the nursing fathers of the Commonwealth," and above all was "God the Father."

Thus the patriarchy of the Old Order was reinforced at every level of social organization and belief. For women, it was total, inescapable. Rebellious women might be beaten privately (with official approval) or punished publicly by the village "fathers," and any woman who tried to survive on her own would be at the mercy of random male violence.

Descriere

The authors present provocative new perspectives on female history, the history of American medicine and psychology, and the history of child-rearing unlike any other.

Notă biografică

Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English