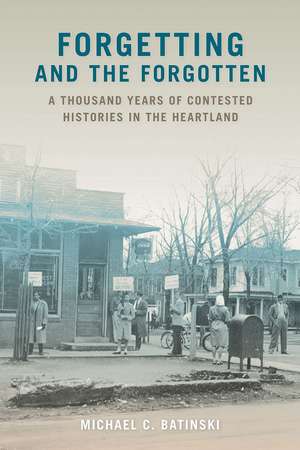

Forgetting and the Forgotten: A Thousand Years of Contested Histories in the Heartland: Shawnee Books

Autor Michael C. Batinskien Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 ian 2022

Revealing the forgotten in community histories

Histories try to forget, as this evocative study of one community reveals. Forgetting and the Forgotten details the nature of how a community forged its story against outsiders. Historian Michael C. Batinski explores the habits of forgetting that enable communities to create an identity based on silencing competing narratives. The white settlers of Jackson County, Illinois, shouldered the hopes of a community and believed in the justice of their labor as it echoed the national story. The county’s pastkeepers, or keepers of the past, emphasizing the white settlers’ republican virtue, chose not to record violence against Kaskaskia people and African Americans and to disregard the numerous transient laborers. Instead of erasing the presence of outsiders, the pastkeepers could offer only silence, but it was a silence that could be broken.

Batinski’s historiography critically examines local historical thought in a way that illuminates national history. What transpired in Jackson County was repeated in countless places throughout the nation. At the same time, national history writing rarely turns to experiences that can be found in local archives such as court records, genealogical files, archaeological reports, coroner’s records, and veterans’ pension files. In this archive, juxtaposed with the familiar actors of Jackson County history—Benningsen Boon, John A. Logan, and Daniel Brush—appear the Sky People, Italian immigrant workers, black veterans of the Civil War and later champions of civil rights whose stories challenge the dominant narrative.

Din seria Shawnee Books

-

Preț: 156.57 lei

Preț: 156.57 lei - 23%

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 139.40 lei

Preț: 139.40 lei - 20%

Preț: 152.33 lei

Preț: 152.33 lei -

Preț: 107.63 lei

Preț: 107.63 lei -

Preț: 82.07 lei

Preț: 82.07 lei -

Preț: 112.78 lei

Preț: 112.78 lei - 25%

Preț: 199.91 lei

Preț: 199.91 lei - 17%

Preț: 335.44 lei

Preț: 335.44 lei - 28%

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 96.50 lei

Preț: 96.50 lei - 21%

Preț: 185.21 lei

Preț: 185.21 lei - 21%

Preț: 257.71 lei

Preț: 257.71 lei - 15%

Preț: 367.79 lei

Preț: 367.79 lei -

Preț: 181.23 lei

Preț: 181.23 lei -

Preț: 248.59 lei

Preț: 248.59 lei -

Preț: 258.86 lei

Preț: 258.86 lei -

Preț: 222.99 lei

Preț: 222.99 lei

Preț: 266.62 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 400

Preț estimativ în valută:

51.02€ • 53.07$ • 42.12£

51.02€ • 53.07$ • 42.12£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809338375

ISBN-10: 0809338378

Pagini: 268

Ilustrații: 8

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Shawnee Books

ISBN-10: 0809338378

Pagini: 268

Ilustrații: 8

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 30 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Ediția:First Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Seria Shawnee Books

Notă biografică

Michael C. Batinski, a professor emeritus of history at Southern Illinois University Carbondale, first expressed his interest in historical consciousness in small places by writing Pastkeepers in a Small Place: Five Centuries in Deerfield, Massachusetts. He is also the author of two books on early American politics, The New Jersey Assembly, 1738–1775: The Making of a Legislative Community and Jonathan Belcher: Colonial Governor.

Extras

Preface

One time, while standing on the bank of the Mississippi River at Grand Tower, the question was put to me: why wasn’t I writing a history of this place? I remember that moment, meditating before the powerful waters pushing south. I do not remember my reply. I was fumbling for words and feeling discomfort. But I could not forget the question.

Slowly, often unawares, I began to address the question.As I listened to neighbors express deep, even passionate, interest in their local history and as I pored through piles of local histories for my research on early America, I became fascinated with the people who kept their local pasts, be they New Englanders or Midwesterners. I was beginning to answer the question but in a way I had not first imagined. What fascinated was not what really happened but the people who cared enough to keep their local pasts and how they arranged their stories—in short something called historical consciousness.

But I had not yet returned to that riverbank. Instead, for personal reasons, I began with pastkeepers in small New England town. As I explored the ways that people in Deerfield, Massachusetts, had kept their past, I was learning two lessons. First, beneath the habits of remembering lay persistent habits of forgetting. That subject—forgetting—became the focus of this second project. Second, I came to understand that the sense of rootedness that moved the people of this New England town had been moving me as well. Born in a town next door, I had spent important portions of my formative years exploring that local past with my parents. And so I returned to the Mississippi riverbank in Jackson County, Illinois, where I had made my home for nearly half my life.

While satisfied with my inner motives, I moved forward always mindful of my method. I had once considered a comparison of four communities when I realized that forgetting by its very nature led me to the hidden, the marginal experiences and muted voices at the edge of community and thereby dictated tight focus on a single place. At the same time, I had read enough local histories in the Midwest and throughout the country to discern common cultural patterns embedded in those works.

Throughout this exploration, I continued to learn from a dear friend from graduate school. Peter Carroll and I have been exploring the hidden niches in this land: the river towns on the Mississippi from Minneapolis to Natchez, small black communities in eastern Oklahoma, the rural world of the Dakotas and later Nebraska and Kansas, Pine Ridge and Medicine Wheel. While Peter lives the life of a poet and I remain an historian, I have learned from our talks and am satisfied that this story of forgetting is repeated throughout the Midwest and beyond.

Introduction

Forgetting lies near the heart of community life by sustaining a shared sense of identity. It is the silent and indispensable partner of remembering. By connecting their present to past--by remembering--neighbors fix themselves in place and time, affirm who they are, and thereby create for themselves a usable past. In doing so they keep what they deem significant--useful--and sweep aside other portions of the past as irrelevant. While forgetting they make themselves vulnerable to experience and to dissenting voices on the edge. The process demands work and is forever meeting resistance. This is a story of the varieties of historical consciousness as they slide past and grate against one another in one Illinois county on the Mississippi River. But the story might be any community in the Midwest.

In short, this book pursues three themes: first, the beliefs guiding the creation of a dominant narrative; second, the habits of forgetting lying within this process; and third, the interplay between the dominant narrative and those lurking at the margins, demanding attention.

In the nineteenth century, no sooner had Jackson County been planted than storytellers and writers began work to create a local history that became a dominant synthesis by the century’s end and continued well into the next. While dominant, this narrative remained fragile, always undermined by not only experience and but also by weaknesses internal to the story. Always vulnerable, the story rested on stubborn imagination. The story line began with origins—settlement, the domestication of wilderness—and developed with civilization’s steady improvements. Implicit in that telling was whiteness—of white settlement even while native and black voices could be heard telling their own and contradictory stories (chapters one and two). Haunted by the native, the pastkeepers’ narrative was vulnerable to translation into an account of dispossession. Thus, their history required the erasure of eight hundred years. So too, the whiteness of the story required concerted efforts to push the experience of black people to the edge. The story of settlement which carried the domestication of the wilderness could easily be turned into a tale of violence. The tellers of the story themselves carried family memories of blood shedding that stretched continuously over generations from the Appalachian frontier, into the Illinois territory, and forward into the trans-Mississippi west. While settlement carried connotations of rootedness, experience suggested that this county was instead a waystation. Transient workers, farmers who tried their luck and disappeared were integral to the county’s life. The pastkeepers themselves knew; they could not suppress this wanderlust (chapter three). The Civil War affected life in ways that did not comport with the prevailing historical consciousness (chapter four). While the war provoked violent civil conflict within the county, forced whites to reconsider the whiteness of their community, and left veterans physically and emotionally scarred, the pastkeepers stubbornly perpetuated their narrative of whiteness and domesticity and thereby erased both a growing black presence and a pervasive personal trauma. In the Gilded Age, this narrative achieved synthesis powerful enough to elide over continuing violence in the form of labor conflict and race (chapter five).

These habits of forgetting were so deeply embedded in historical consciousness that the dominant pastkeepers were able to look at, even document, the dissonances without troubling themselves to reflect on their significance. Part Two examines two themes in local historiography that illustrate the crippling effects on imaginations from the nineteenth well into the twentieth century. Class (chapter 6) and race (chapter 7) were hiding in plain sight throughout. Even while historians sought to gloss over these subjects, they could not erase. Laborers and capitalist investors, black people and American Indians appear momentarily as if asides. Not only could voices expressing alternative tellings of county history be heard, the dominant pastkeepers heard them. Yet, even while espousing the ideal of a democratic history that included the commons, their imaginations froze. By comparison environmental degradation and gender remained tucked far below the surface, rarely troubling imaginations even momentarily. Neither subject posed a continuous challenge to historical imaginations until the late twentieth century and after this book’s conclusion. That class and race lay so near the surface, persistently challenging the pastkeepers, documents most clearly the efforts to forget.

This is the story of historical imaginations grating against one another, of power, and its limits. Its purpose is not to correct or to replace one rendering of the past but to recount the way competing historical perspectives occupied the same space. The struggle for a usable past and community identity turns on beliefs and ideas. Whatever their limitations, they remain essential for understanding community life.

This project focuses on a small niche in the landscape and is informed by attending to the larger scene. A single place seemed appropriate to a study of the habits of forgetting in a small place. By its nature the forgotten is tucked away in dark corners and can be discovered by prowling through piles of obscure sources. The interplay between habits of forgetting and remembering can best be understood by careful attention to a small place. What transpired in Jackson County was repeated in countless places throughout the region, indeed the nation. But for specific detail other local histories mirror the narrative structure found in this county’s pastkeepers. Moreover, these histories of small places do bear a relationship to the dominant national narrative. On first glance, they include little of relevance to the national histories: they appear to be histories of places where nothing seemed to happen. Yet closer attention reveals an organization shared by both historiographies. Jackson County’s white settler narrative served as corroboration of a spread-eagle national story. In recent years, Americans have come to question that story and peer into the dark corners of the past to discover the forgotten. That process of self-examination informs this work as well.

[end of excerpt]

One time, while standing on the bank of the Mississippi River at Grand Tower, the question was put to me: why wasn’t I writing a history of this place? I remember that moment, meditating before the powerful waters pushing south. I do not remember my reply. I was fumbling for words and feeling discomfort. But I could not forget the question.

Slowly, often unawares, I began to address the question.As I listened to neighbors express deep, even passionate, interest in their local history and as I pored through piles of local histories for my research on early America, I became fascinated with the people who kept their local pasts, be they New Englanders or Midwesterners. I was beginning to answer the question but in a way I had not first imagined. What fascinated was not what really happened but the people who cared enough to keep their local pasts and how they arranged their stories—in short something called historical consciousness.

But I had not yet returned to that riverbank. Instead, for personal reasons, I began with pastkeepers in small New England town. As I explored the ways that people in Deerfield, Massachusetts, had kept their past, I was learning two lessons. First, beneath the habits of remembering lay persistent habits of forgetting. That subject—forgetting—became the focus of this second project. Second, I came to understand that the sense of rootedness that moved the people of this New England town had been moving me as well. Born in a town next door, I had spent important portions of my formative years exploring that local past with my parents. And so I returned to the Mississippi riverbank in Jackson County, Illinois, where I had made my home for nearly half my life.

While satisfied with my inner motives, I moved forward always mindful of my method. I had once considered a comparison of four communities when I realized that forgetting by its very nature led me to the hidden, the marginal experiences and muted voices at the edge of community and thereby dictated tight focus on a single place. At the same time, I had read enough local histories in the Midwest and throughout the country to discern common cultural patterns embedded in those works.

Throughout this exploration, I continued to learn from a dear friend from graduate school. Peter Carroll and I have been exploring the hidden niches in this land: the river towns on the Mississippi from Minneapolis to Natchez, small black communities in eastern Oklahoma, the rural world of the Dakotas and later Nebraska and Kansas, Pine Ridge and Medicine Wheel. While Peter lives the life of a poet and I remain an historian, I have learned from our talks and am satisfied that this story of forgetting is repeated throughout the Midwest and beyond.

Introduction

Forgetting lies near the heart of community life by sustaining a shared sense of identity. It is the silent and indispensable partner of remembering. By connecting their present to past--by remembering--neighbors fix themselves in place and time, affirm who they are, and thereby create for themselves a usable past. In doing so they keep what they deem significant--useful--and sweep aside other portions of the past as irrelevant. While forgetting they make themselves vulnerable to experience and to dissenting voices on the edge. The process demands work and is forever meeting resistance. This is a story of the varieties of historical consciousness as they slide past and grate against one another in one Illinois county on the Mississippi River. But the story might be any community in the Midwest.

In short, this book pursues three themes: first, the beliefs guiding the creation of a dominant narrative; second, the habits of forgetting lying within this process; and third, the interplay between the dominant narrative and those lurking at the margins, demanding attention.

In the nineteenth century, no sooner had Jackson County been planted than storytellers and writers began work to create a local history that became a dominant synthesis by the century’s end and continued well into the next. While dominant, this narrative remained fragile, always undermined by not only experience and but also by weaknesses internal to the story. Always vulnerable, the story rested on stubborn imagination. The story line began with origins—settlement, the domestication of wilderness—and developed with civilization’s steady improvements. Implicit in that telling was whiteness—of white settlement even while native and black voices could be heard telling their own and contradictory stories (chapters one and two). Haunted by the native, the pastkeepers’ narrative was vulnerable to translation into an account of dispossession. Thus, their history required the erasure of eight hundred years. So too, the whiteness of the story required concerted efforts to push the experience of black people to the edge. The story of settlement which carried the domestication of the wilderness could easily be turned into a tale of violence. The tellers of the story themselves carried family memories of blood shedding that stretched continuously over generations from the Appalachian frontier, into the Illinois territory, and forward into the trans-Mississippi west. While settlement carried connotations of rootedness, experience suggested that this county was instead a waystation. Transient workers, farmers who tried their luck and disappeared were integral to the county’s life. The pastkeepers themselves knew; they could not suppress this wanderlust (chapter three). The Civil War affected life in ways that did not comport with the prevailing historical consciousness (chapter four). While the war provoked violent civil conflict within the county, forced whites to reconsider the whiteness of their community, and left veterans physically and emotionally scarred, the pastkeepers stubbornly perpetuated their narrative of whiteness and domesticity and thereby erased both a growing black presence and a pervasive personal trauma. In the Gilded Age, this narrative achieved synthesis powerful enough to elide over continuing violence in the form of labor conflict and race (chapter five).

These habits of forgetting were so deeply embedded in historical consciousness that the dominant pastkeepers were able to look at, even document, the dissonances without troubling themselves to reflect on their significance. Part Two examines two themes in local historiography that illustrate the crippling effects on imaginations from the nineteenth well into the twentieth century. Class (chapter 6) and race (chapter 7) were hiding in plain sight throughout. Even while historians sought to gloss over these subjects, they could not erase. Laborers and capitalist investors, black people and American Indians appear momentarily as if asides. Not only could voices expressing alternative tellings of county history be heard, the dominant pastkeepers heard them. Yet, even while espousing the ideal of a democratic history that included the commons, their imaginations froze. By comparison environmental degradation and gender remained tucked far below the surface, rarely troubling imaginations even momentarily. Neither subject posed a continuous challenge to historical imaginations until the late twentieth century and after this book’s conclusion. That class and race lay so near the surface, persistently challenging the pastkeepers, documents most clearly the efforts to forget.

This is the story of historical imaginations grating against one another, of power, and its limits. Its purpose is not to correct or to replace one rendering of the past but to recount the way competing historical perspectives occupied the same space. The struggle for a usable past and community identity turns on beliefs and ideas. Whatever their limitations, they remain essential for understanding community life.

This project focuses on a small niche in the landscape and is informed by attending to the larger scene. A single place seemed appropriate to a study of the habits of forgetting in a small place. By its nature the forgotten is tucked away in dark corners and can be discovered by prowling through piles of obscure sources. The interplay between habits of forgetting and remembering can best be understood by careful attention to a small place. What transpired in Jackson County was repeated in countless places throughout the region, indeed the nation. But for specific detail other local histories mirror the narrative structure found in this county’s pastkeepers. Moreover, these histories of small places do bear a relationship to the dominant national narrative. On first glance, they include little of relevance to the national histories: they appear to be histories of places where nothing seemed to happen. Yet closer attention reveals an organization shared by both historiographies. Jackson County’s white settler narrative served as corroboration of a spread-eagle national story. In recent years, Americans have come to question that story and peer into the dark corners of the past to discover the forgotten. That process of self-examination informs this work as well.

[end of excerpt]

Cuprins

Contents

Preface

Introduction

Part One: Forgetting Habits

1. Dispossessing: Land and Past

2. Squaring the Circles, Filling the Squares

3. Settlers and Transients

4. Civil Wars and Silences

5. Gilding the Past

Part Two: Habits Kept, Habits Questioned

6. Passersby, Rich and Penniless

7. Reconstruction and Race

Conclusion

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Preface

Introduction

Part One: Forgetting Habits

1. Dispossessing: Land and Past

2. Squaring the Circles, Filling the Squares

3. Settlers and Transients

4. Civil Wars and Silences

5. Gilding the Past

Part Two: Habits Kept, Habits Questioned

6. Passersby, Rich and Penniless

7. Reconstruction and Race

Conclusion

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Recenzii

“The writing of history and the creation of collective memories and identities is often about power—those who have it and those who do not. Michael C. Batinski’s Forgetting and the Forgotten shows how constructions of past are made—both traditional narrative and the counter narratives that challenge many of their assumptions and assertions by members of communities that have had different experiences.”—Terry A. Barnhart, author of Albert Taylor Bledsoe: Defender of the Old South and Architect of the Lost Cause!

“This is an exquisitely crafted study that highlights the ways that local pastkeepers in Jackson County, Illinois, marginalized and silenced Native American, African American, and working-class experiences and stories.”—Sean Farrell, coauthor of The Irish in Illinois

“Undoubtedly one of the best two books this year. A unique look and local and state history, engaging reflections on race, class, and ethnicity. Provides much needed historical discussion for Jackson County and Southern Illinois University.”—Illinois State Historical Society Awards Selection Committee

“This is an exquisitely crafted study that highlights the ways that local pastkeepers in Jackson County, Illinois, marginalized and silenced Native American, African American, and working-class experiences and stories.”—Sean Farrell, coauthor of The Irish in Illinois

“Undoubtedly one of the best two books this year. A unique look and local and state history, engaging reflections on race, class, and ethnicity. Provides much needed historical discussion for Jackson County and Southern Illinois University.”—Illinois State Historical Society Awards Selection Committee

Descriere

Forgetting and the Forgotten details the nature of how a community forged its story against outsiders. Historian Michael C. Batinski explores the habits of forgetting that enable communities to create an identity based on silencing competing narratives.