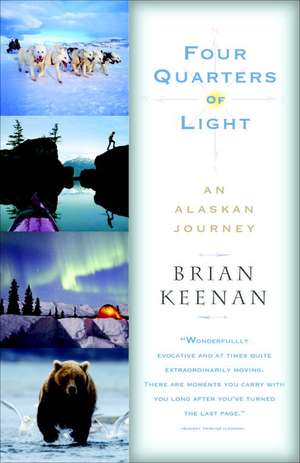

Four Quarters of Light: A Journey Through Alaska

Autor Brian Keenanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 aug 2006

From dog-mushing on a frozen lake beneath the colors of the aurora borealis to camping in a two-dollar tent in the tundra of the Arctic Circle, from skinning hides with an aging shaman and his wife to boating in the stormy Bering Sea, and along frozen inlets to a remote Eskimo fishing camp, Keenan seeks out the ultimate wilderness experience and connects with a spectrum of wildlife, including his own “spirit bear,” all of them roamers in “The Big Lonely.” En route, he encounters hard-core survivalists who know what struggle and endurance mean from their daily battle for existence. And finally, he discovers that true wilderness is as much a state of mind as it is a place and that ultimately, to make Alaska home, one must surrender to the land.

Preț: 92.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.63€ • 18.26$ • 14.71£

17.63€ • 18.26$ • 14.71£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780767923255

ISBN-10: 0767923251

Pagini: 364

Dimensiuni: 136 x 203 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0767923251

Pagini: 364

Dimensiuni: 136 x 203 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

BRIAN KEENAN is the author of An Evil Cradling, his classic account of his years as a hostage in Beirut. He lives in Ireland.

Extras

1

Instructions and Preparations

From where I sit at my study window in Co. Dublin, I can see the rolling swell of the Wicklow hills. On stormy nights, if I walk to the end of the short terrace of which my house is the last but two, I can hear the sea’s turbulence. As I look at the quaintly named Sugar Loaf mountain, I think that such a hill would not register in the landscape of the far Alaskan Northland. In a panorama that has one’s head turning in a hypnotic 360-degree movement, in a mountainscape of fantastic dimensions such as you would only imagine in the illustrations of a mythic saga, such a pathetic headland would not even merit a nod.

Horizons are neither fixed nor finished in the Northland. Any horizon that presents itself to you only marks the limit of your vision; far beyond what you see, you know there is more. Another rugged mountain range, another somewhere, probably nameless and likely uninhabited. Only migratory birds, in their hundreds of thousands, know this landscape intimately. We poor land-bound, sight-blighted creatures can only grasp at things with our imagination and stumble over words such as permafrost, tundra and boreal forest, hot springs and pack ice, aurora borealis and midnight sun. They are all phenomena particular to the far north, but to me they are more than that: they are magic words, like a fistful of polished bone thrown from some shaman's hand. In them you might discover more of yourself than you know. Perhaps that's why I went to the final frontier — for the magic, before my own bones were too feeble for the task.

But an old man's romance is not enough for an answer; in any case, romance belongs to the rocking chair and recollection. We go places for our own reasons, even if we only half understand them. On the closing page of Between Extremes, an account of my travels in Patagonia and Chile co-authored with John McCarthy, I wrote, "I sensed that the only important journey I would make henceforth would be journeys out of time and into mind. There was another landscape to be discovered and negotiated. The landscape of the heart, the emotions, and the imagination had to be opened up and new route maps plotted ... We talked late into the night arguing whether or not we, too, have journeys mapped on our central nervous systems. It seemed the only way to account for our insane restlessness."

So how could I now account for my own restlessness and my insistence on travelling to Alaska? It seemed to stand in contradiction to my deeply felt resolve at the conclusion of my South American travels. If I had determined that the only journeys I would make should be into the imagination and the landscape of the heart, then why was I thinking again of the Alaskan wilderness? For it was more than an old man's romantic folly, if not best forgotten then consigned to wishful thinking. The idea of an undiscovered country set in an elemental landscape fascinated me. It appealed to my anarchistic notions of boundless freedom. Sure it was romantic, but it was also real. Alaska was not a figment of my imagination. It existed in time and in place, and in my mind as somewhere that might test my self-assurance. One thing was for sure: it was clearly written on the map of my central nervous system.

It's a long way from Avoniel Road, where I went to school, to Alaska, where I dreamed of going, and the distance is in more than miles and physical geography. After all, what correspondence could there be between Belfast in the north of Ireland and Barrow in the far north of the Arctic Circle? But Avoniel primary school in east Belfast gouges itself up out of my memory as an original point of departure. It was 1959, and I was approaching my tenth birthday. I was a "good child", as my mother described me, quiet and untroublesome.

The school was a big, two-storey barracks of a building, solid and imposing, set among the maze of back streets it served. A great lawn of two junior-sized football pitches stretched out in front of it. To the right and screened from the entrance was a concrete netball pitch, and beside that the boys' and girls' outside toilets. Whatever advantage the 1947 Education Act had provided for the children of the area it did not accommodate indoor plumbing. But then this was the catchment area of the aircraft factory and the shipyard, and me and my mates were all cannon fodder for the engineering industry. The football pitches were the largest green space in the area but they were forbidden to any of us after school hours. I was not of an athletic disposition anyway, and though I occasionally scaled the railings during the summer holidays it was more because the place was forbidden than out of any desire to kick a football.

I compensated for my lack of sporting skills by finding a refuge in books. I excelled at reading and had finished all the "readers" we were required to make our way through long before my peers. If I was always the last kid picked to play, I was equally the first to complete any reading tasks, and I had more gold stars than anyone in my class. My special reward for being so far in advance of the rest of my classmates happened the day my teacher called me aside and suggested I might like to choose a book from the library. The library in Avoniel was an old Welsh dresser with locked doors stationed at the end of the first-floor corridor. It was also where the classrooms for the kids about to go to the "Big" school were located, and the library was exclusively for their use. The upper shelves were full with about three dozen books. I remember being quite frightened as my teacher walked me out of the class, admonishing the rest of the kids to be quiet and get on with their work until we returned. Whatever alienation I had felt from the rest of my mates, it was now compounded by this "honour". I was nine at the time and should not have been using the library for another year or two.

Standing on the rickety chair scanning the book spines in front of me, I felt like a sacrifice; these books were teeth in the great God monster that was going to devour me.

"You pick one, sir," I said, immobilized and wanting to be away from this looming altar of words.

The teacher laid his hand on my shoulder and in a voice that conveyed neither sympathy nor enthusiasm pronounced, "No, young man, you're going to read it, so you choose it."

I had never felt so alone in my life. Again I scanned the books before me. Their titles were just a jumble of words that meant little to me and only added to my confusion. Then my eyes alighted on one book; the four words comprising its title were easy for my young mind to read. The conjunction of the words were intriguing and the stark image on the dust cover of a large dog howling into a richly coloured sky impressed itself upon me. I picked it out, climbed down from the chair and handed the book in silence to the teacher.

He took it from me and announced the title to the empty corridor: "The Call of the Wild." He smiled thinly and continued, "So, you like dogs, do you?"

I answered him automatically, the words spilling from me. "Yes, sir. My dog at home is called Rex!"

His smile hung there for another moment, then he said, "It may be a little difficult for you, Keenan, but it is a great adventure story. Try it, and we'll see how it goes." I held out my hand to take the book. "I'll bring the chair and you bring your dog!" he added, handing me the book.

For more than forty years I have had that dog with me, and the call of the wild echoes in me still. The story of Buck has, it seems, permeated the whole of my growing up, and here I am in my fifties still enraptured with it, the author and the landscape that gave it birth. The Call of the Wild is a parable about surviving and overcoming against all odds. It is about struggle and fulfilment, and it is ultimately about becoming what is in one to become. The call of Alaska's wilderness became a siren song; to resist it was to smother a vital instinct in myself. Maybe mortality and old age were knocking on my door and maybe I was not ready to let them in. There was another place I needed to go first. The last sentence of The Call of the Wild still speaks profoundly to me about the mystery and magic of that place, and about the torment of the author who wrote so eloquently about it: "When the long winter night comes and the wolves follow their meat in the lower valleys he may be seen running at the head of the pack through the pale moon light on glimmering borealis, leaping gigantic above his fellows, his great throat a bellow as he sings the song to the younger world, which is the song of the pack."

Still, I don't know if it was my solitary childhood immersion in Jack London's barbaric Northland that created my yearning. Isolated and barren landscapes draw me to themselves, different places for different reasons, but the one constancy is the lure of emptiness and wilderness. I suppose I feel comfortable there, untroubled. I can imagine a recreated life, and I confess a part of me is a loner. Loneliness, isolation and empty spaces are, I suppose, the preconditions of the dreamer, and I am a dreamer, unreconstructed and uncompromising. I pursue the landscape of the imagination and seek to find in the world about me some correspondence between the external and inner worlds, or perhaps a trigger for their coming together.

All journeys for me have this dual nature. But Alaska is no dreamland. It is raw, wild, primordial and uncompromising. Forsaking the holy grail of the imagination and emotion for a Klondike chronicle might be more demanding of the traveller than I could conceive. But only when you really contemplate it do you begin to slowly comprehend that Alaska is as complex as it is large.

For a start, it comprises several time zones and climatic regions. There are a minuscule number of roads for a region larger than England, France, Germany, Italy, Holland and Ireland put together. Negotiating such a vast expanse would be a nightmare of logistics, and as I intended to take my family with me I was multiplying my problems fourfold. But there was no way I could leave them behind. Maybe I was afraid the emptiness might engulf me, but my intoxication with the call of the wild was spilling over into my family life. I wanted to take my sons to see the place that had embedded itself in me when I was a child.

One belief I hold as an absolute truth is that the mind forgets nothing. I might forget things, but my mind forgets nothing. My sons were younger than I was when I was first smitten with Alaska. They might not enjoy months of living like the Swiss Family Robinson in the wilderness. I might not myself. Perhaps the illusion would evaporate there. Perhaps I had made too big an investment from my childhood in this imagined land. But that would be for me to resolve. Even if in the years to come my sons forgot their stay in Alaska, they would still have it stored in their memory bank to revisit over time, as I had done on many occasions. I only wanted to reveal to them the place that had continued to inspire me. I wanted Alaska to be more than their old man's ramblings. It could become for them whatever they chose. They only needed the seeds planted in them by exposure to the place, just as they had been implanted in me by exposure to Jack London's calling wilderness.

But there was another curious incident that swept the winds of Alaska right into my home and made my visit an imperative. I had visited Fairbanks in central Alaska several years earlier as a guest lecturer. My stay was brief and confined to the environs of Fairbanks and its university, but it was enough to seal my long-held fascination with the place. While there I spoke with a group of students and some members of the public who attended my lecture as non-registered students about the use of the "instinct" in the creative process. I happened to mention that I had a notion to write a book about a blind musician, and as I knew nothing about music and was not blind I hoped my instinctual facilities were in good order.

I soon forgot the incident, but was brought sharply back to it while in the process of writing the book. I had spent years researching my subject and was tortuously trying to put the fiction together: I was finding it hard going trying to imagine the life of an eighteenth-century blind harpist, Turlough Carolan. Several months into the task I was about to give up and forget the project, though it remained very close to my heart. I was locked in one of those imaginative and intellectual culs-de-sac and was beginning to question the validity of what I was writing about. The whole thing seemed pointless.

At the very time I was contemplating this, I received a letter with a Fairbanks postmark. The letter was brief with no return address, the handwriting tiny but neat. It looked and felt feminine to me but I could not make out the signature. It informed me that its author was aware I had intended writing a book about Turlough Carolan, who was a "Dreamwalker". The word threw me totally. I had not come across it before and never in reference to my subject. Mainly due to frustration with the lack of empathetic engagement with my subject, I dismissed the letter as having been written by some demented old spinster in the Alaskan outback who filled her days by writing strange letters to complete strangers.

I persevered with the book, stumbling into blind alleys and raging out of them. I wanted to get inside the emotional and psychological persona of the man I was writing about, but the fact that I wasn't blind combined with a marked musical illiteracy was making the book impossible. After months of struggle I finally came to the conclusion that I should jettison the project. Though I had promised myself for years that I would write the story of Turlough, I felt I had come to the end of the road.

Then another letter with an Alaskan postmark arrived, again with no return address, the same female handwriting and the same obscure signature. This time the letter was less brief, but the word "Dreamwalker" was back on the page and intriguingly there was an explanation of the term. I no longer have the letter, nor do I remember the exact words, but the imprint of it remains with me. Briefly, it related that the "Dreamwalker", whoever that may be (in my case Turlough), comes to visit people in their dreams. Their purpose is to give something, usually something healing and usually something that has to be passed on.

For some reason the letter seemed to take hold of me. I read it over and over again, then paced the floor trying to come to terms with the information and its relation to my work. I meticulously tried to decipher the signature and thought I could make out an Inuit name. But I could not be sure. The timing and the content of her letters seemed otherworldly. What was this strange Inuit woman from somewhere in Alaska trying to tell me? Why were her "Dreamwalker" letters always arriving at the precise moments of creative crises in my life? What was the connection between her and my long-dead blind musician? And what was my part in the weird triangle? I thought about it over and over again. It was like trying to work out some unearthly trigonometry.

Then, from God knows where, it hit me like a slap in the face. My torpor lifted and I was shown the way out of my dilemma. If my eighteenth-century itinerant musician had walked intomy dreams then I need only walk in his. In writing out his blind dreams I could convey his psychic and emotional life, thus extrapolating out of the man himself how he lived, how he composed the music he did, and why.

I finished the book with my muse from Alaska driving and directing the story. Sometimes I look at it on the bookshelf in my study and think how it would not be there, indeed how it would not exist in any form, had I not received those mysterious letters from the Alaskan wilderness. I had rid myself of my eighteenth-century musician but a new and more prescient Alaska was calling to me with irresistible attraction. It had now given itself a voice that was separate from my own fantasizing. So I chose to return with a head full of questions about that inspiring landscape and the primitive animism that exists there.

Jack London once wrote in a letter, "When a man journeys into a far country, he must be prepared to forget many things he has learned, he must abandon the old ideals and the old gods and often times he must reverse the very codes by which his conduct has hitherto been shaped." There was something in those words of London's that excited my imagination about my mysterious pen friend, and the magic that connected us. She was not just some figment of my frustrated imagination, she was real and living out there in the boundless wilderness. Her communications had moved psychic mountains for me, and the acknowledgement on the flyleaf of the book hardly seemed sufficient reward. But could I find her in that huge country? If I was to accept London's words, what would I have to abandon, and what reverses would I have to make? For a moment I thought of Joseph Conrad's failed heroes who are devoured by the landscape they enter, and I recoiled at the journey that was beckoning me.

I thought again of London and the struggles of his heroes, men and dogs, against the forces of nature and one another. His stories embody a recognition of primal forces that can transform or crush people, at the same time hinting at something in the personality of their author, an illegitimate child whose poverty-stricken childhood taught him how to fight to survive. Like myself, the author would take himself off on small voyages of discovery, surviving on his wits and animal cunning. As a man, he was strongly influenced by Marx, Hegel, Spencer, Darwin and Nietzsche, from whose works he evolved a belief in humanism and socialism and an admiration for courage and individual heroism. I was drawn to this complex, tragic man. A writer who wrote in the naturalist tradition of Kipling and Stevenson. A Marxist who flirted with dangerous notions of the superhero. A socialist who argued against the Mexican Revolution. But, ultimately, a man who drew his own map in life. In many respects London was like one of his strongest characters. In The Sea Wolf (1904), Wolf Larsen is the incredibly brutal but learned captain of the Ghost who is doomed by his individualism. The central character of Mark Eden was also ominously autobiographical, not only telling of an ex-sailor who becomes a writer but also of the emotional turmoil, the loss of identity and selfhood and ultimate suicide. Maybe the author's idealism was too highly pitched. He was shipwrecked by failed marriages, bankruptcy, alcoholism and suicide. Obviously there had been some dark, self-destructive alter ego that would not allow the man to "reverse the very codes by which his conduct has hitherto been shaped". He certainly had much to say about fear. He considered it mankind's basic emotion, a kind of primordial first principle that affects us all. But understood in the right way, fear need not be a harness. London's protagonists challenged it, even chose at times to forget it. Fear was a prime motivator for London the man, too: it made him shake off the shackles of conformity and achieve success.

"There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise," he once said. I had unknowingly tasted that ecstasy as a child with my face buried in the author's epic in a tiny two-up-two-down family home whose confines smothered me. In the Belfast back streets where the only green space was locked away from me behind iron railings I drank deeply from London's elixir and its taste stayed in my mouth. Foolishly or not, when I was younger I was a man who was afraid of being afraid. It forced me to make choices and flooded me with questions I felt only the Northland itself could answer. But I was older now and hopefully a little wiser. Maybe I was tired of being afraid of being afraid. If I was to "forget many things .". . abandon the old ideals and the old gods . . . and reverse the very codes that had formed me then perhaps I could only fully reclaim this lost part of myself during a wilderness experience.

Was Alaska still peopled with those quirky, eccentric and reclusive individuals that made Robert Service famous and fascinated London? Service's rhythmic and zestful poems about the rugged life of the Yukon were also part of my growing up. "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" and "The Cremation of Sam McGee" were in every school anthology and brought the Canadian outback into our mundane school days. Alaska was called the "Final Frontier" before the writers of Star Trek hijacked the phrase, and I wondered if it still had the same kind of allure for people as it had for its most famous writers. What impels people towards finality and the last place on earth, and what do they resolve there? Why do they stay in the seemingly inhospitable land? Have they a perverse sense of beauty akin to my own? If so, how do they understand it? These were my questions, and neither London nor Service could answer for me.

Maybe the Final Frontier is an inaccurate description, for assuredly Alaska is the Frontier of Fable. The onion-domed churches of nineteenth-century Russian Orthodoxy still break up the skyline around Juneau, Sitka and Kodiak. Further north the Inuit peoples cling to their religious beliefs with their shamanism and an animistic respect for the natural world from which we all could learn much. And everywhere one still finds those curious, rugged, idealistic individuals who have washed up in this vastness, and perhaps it's the proper place for them, for here the emptiness is big enough to contain their madness. Only a place as immense as Alaska can properly contain a fevered imagination. This is the land that Swift, C. S. Lewis and Tolkien never discovered, as fantastical as a fairy-tale but undersewn with deep soul-searching.

I began to pore over maps of Alaska. But any map of Alaska is a Spartan illustration: railway lines and road systems are conspicuous by their absence and Juneau, the state capital, is accessible only by air and sea. The state is more easily measured in time zones than miles. It contains four such zones and a total population of just over 600,000, half of whom reside in Anchorage, Alaska's largest town and port; the rest of the population is spread out across this massive, seemingly endless state in communities that make the map look more like a join-the-dots picture such as you find in children's colouring books. But this is no childhood fantasy land. The incomprehensible hugeness of the place is something to be wary of. I remember a friend I had met during my first brief visit to Alaska saying, "Be careful when you're reading maps in Alaska. Names don't always mean places and named places don't always guarantee that people live there. There are some communities in Alaska where people live so far from one another that they are all but invisible. That kind of landscape doesn't only make you feel small, it can be very scary and very dangerous too."

I thought over my friend's words as I scanned the place names spread out before me. The Inuit names scattered around the margins of the landmass were curious and almost unpronounceable; my tongue tripped over glottal stops as I tried to say them: Unalakleet, Koyukok, Umiat, Shungnak and Shageluk, Akhiok, Ekwok, Quinhaqak, Togiak and Yakutat. Then the curious European names that marked the commercial expansion — and settlement: Russian Mission and Holy Cross, Valdez and Cordova, and the place names of the miners who had come in droves, desperately poor, dream-driven men whose rudimentary education made them believe their dreams and give names to places the way you would throw scraps to a dog. The names were simple, yet just reading them brought you very close to their world: Livengood, Sourdough, Chicken, Coldfoot, Eureka. Then there were the mountains, from Mount McKinley, the highest on the continent, to the permanently frozen Brooks Range, the most northerly. The Koskokwim mountains and the Wrangell mountains, and more mountains — the St Elias, the Kilbruck, the Taylor, the Talkeetna, the Asklun, the Romanof, the Shublik — and then the great ranges, the Aleutian and the Alaskan. There were yet more mountains that no-one had bothered to name because no human had ever set foot on them or ever wanted to. Obviously there were some places that refused admission to the human species.

But however brutal, imposing and empty, people had chosen to go there, and to stay. Most assuredly Alaska is not a place one simply stumbles upon. Even in the book of choices this forbidden, inhospitable emptiness would hardly rate in the top twenty of anyone's most desirable places to settle in. Yet native peoples make up only about 20 per cent of the population; the rest are immigrants, or perhaps more correctly self-inflicted exiles. Who were they? Why had they come? What were they running from? And, more importantly, what had they found? How the place had transformed them to make them stay was what I wanted to know. Was there really some kind of magic here, or had the stone-cold landscape frozen their souls and immobilized them? For after Alaska there are no more choices, no more places to go. It is, after all, the Final Frontier.

Poring over maps doesn’t answer questions, it only adds to them, and in the case of Alaska it only served to deepen the enigma of the place and my resolve to return. I was determined that my journey should take me through the four geographical quarters. First, the coastal south-east and the south-central region to hunt down Jack London's first footfalls; then south-west and the Bering Sea coast; then into that light-filled, enclosed world of the Arctic region; and finally into the interior, ranging out from Fairbanks on small voyages of discovery or displacement. I intended travelling only during the period of maximum light, from snowmelt in mid-May to snowfall in mid-September, for I have had more than my share of dark places, and anyway, Alaskan winters are not made for travelling great distances.

As I began to plan the logistics of trying to encompass this vast land, I was ever mindful of Jack London's advice about his Alaskan experience: "It was in the Klondike I found myself. There nobody talks, everybody thinks. You get your perspective. I got mine." I remembered too the author's imperative about being prepared to forget and abandon many things, and concluded it would be impossible and a serious error for me to try to work out a detailed schedule and timetable. The country was too big to be reduced to a precociously planned itinerary. If any journey was simply a record in time of passage between two points then few of us would need to make such journeys; we could simply read the records of others. Rather, a journey is like a work in progress: you extract meaning and insight from the experience.

Alaska was calling me out to its wilderness. Would I be equal to it or would it be unequal to my dreams? There was only one way to find out.

Packing was a nightmare; the problem was as big as the landmass I was venturing into. How does one wind- and weatherproof two adults and two children against climatic conditions that vary between Arctic numb and Mediterranean wet, occasionally bleaching into the high hot days of an Indian summer? I looked at the bags piling up: they too were mocking me. It would take a brigade of army engineers to move this lot or at least a string of pack mules. I intended travelling a lot and the idea of constant packing and unpacking was already defeating me.

I thought it through over and over again. Four time zones,climatic conditions so varied that nothing could be depended on. A road system, in a land of continental dimensions, that amounted to a few hundred miles rather than thousands of miles. I would have to fly long distances in tiny light aircraft, and those that know me know that my fear of heights is legendary. Also I cannot swim and much of the south-east and south-west peninsulas can only be explored by small boat. I was certainly no Grizzly Adams and the logistics of my fanciful expeditions seemed to be impossible. It was like a logarithmic problem that had its resolution somewhere in infinity, and that, seemingly, was where I was going too.

In an attempt to reassure myself and to keep my worst fears from my wife and family, I turned again to my mentor Jack London and considered how he would have handled all this. In a letter to one of his friends he writes of his first encounter with the infamous man-killing Chilkoot trail, which had to be negotiated to enter into that wildness that so fascinated the author and myself.

"The sands of Dyea resemble an invasion beach. Everywhere men bartered with Indian porters, trying to persuade them to haul their food at reasonable prices. Jack's ageing partner Shepard took one look at the glittering white wall of the Chilkoot Pass and decided to turn back. Within weeks, he would be joined by thousands more. In retreat, they would find abandoned kit littering the coastline for forty miles." Despite the Chilkoot Pass's back-breaking nature, by the autumn of 1897 twenty-two thousand men and women had reached the other side. Jack was among them. But only after a struggle which tested his stamina to the limit.

Crippled horses littered the trail, "broken-boned, drowning, abandoned by man". They died "like mosquitoes in the frost. They snapped their legs in the crevices and broke their backs falling backwards on their packs; in the sloughs they sank from sight or smothered in the same, men shot them, worked them to death and when they were gone, went back to the beach and brought more. Some did not bother to shoot them, stripping the saddles off, and leaving them where they fell. Their hearts turned to stone, those which did not break, and they became beasts, the men on Dead Horse Trail."

I looked again at our mountain of luggage and the sparse map, mulling over all the what-ifs that were niggling at me. It seemed I was contemplating my own Chilkoot Pass without having set foot in Alaska. I certainly do not possess the same "will to power" that was so much part of London the man and the writer but I suppose I had a soul hunger akin to his, and if he could survive on that perhaps I could too.

However, no matter how I dealt with the difficulties, most of which were imagined, there were two real problems that would not go away. I was having sleepless nights about the smallest of the inhabitants of this land where everything was big, namely the mosquito and its near cousins the black fly and the suitably named "no-see-ums", whose bites are far more annoying precisely because you cannot see the creature.

Permafrost was another problem. Its constant presence just feet below the surface ensured that plumbing was more than a luxury. In many places it was impossible to install simply because it would never work. I did not dwell on this subject too much with Audrey, but simply explained that she should expect things to be very primitive in some places.

The mosquitoes eventually won out. My Alaskan friend Pat Walsh had warned us not to underestimate their number or their size. To emphasize her point, she sent me a miniature penknife, no more than an inch long, with one small double-sided blade like a paring knife. When I thanked her and queried the purpose of such an ornament she answered curtly: "It's not an ornament, it's for skinning mosquitoes!" I decided to change the order of my travels, visiting "the Bush" first, before the insects got too thick on the ground, then moving on to the Bering Sea coast and the south-east and south-west peninsular regions, where my expectation was that the open space and coastal winds would keep the bugs at bay.

Trying to solve problems before you encounter them is frequently a wise precaution but it can also be a debilitating one. Having convinced myself that it was better to confront the enemy in his own back yard, we headed north to the last frontier, come what may!

Instructions and Preparations

From where I sit at my study window in Co. Dublin, I can see the rolling swell of the Wicklow hills. On stormy nights, if I walk to the end of the short terrace of which my house is the last but two, I can hear the sea’s turbulence. As I look at the quaintly named Sugar Loaf mountain, I think that such a hill would not register in the landscape of the far Alaskan Northland. In a panorama that has one’s head turning in a hypnotic 360-degree movement, in a mountainscape of fantastic dimensions such as you would only imagine in the illustrations of a mythic saga, such a pathetic headland would not even merit a nod.

Horizons are neither fixed nor finished in the Northland. Any horizon that presents itself to you only marks the limit of your vision; far beyond what you see, you know there is more. Another rugged mountain range, another somewhere, probably nameless and likely uninhabited. Only migratory birds, in their hundreds of thousands, know this landscape intimately. We poor land-bound, sight-blighted creatures can only grasp at things with our imagination and stumble over words such as permafrost, tundra and boreal forest, hot springs and pack ice, aurora borealis and midnight sun. They are all phenomena particular to the far north, but to me they are more than that: they are magic words, like a fistful of polished bone thrown from some shaman's hand. In them you might discover more of yourself than you know. Perhaps that's why I went to the final frontier — for the magic, before my own bones were too feeble for the task.

But an old man's romance is not enough for an answer; in any case, romance belongs to the rocking chair and recollection. We go places for our own reasons, even if we only half understand them. On the closing page of Between Extremes, an account of my travels in Patagonia and Chile co-authored with John McCarthy, I wrote, "I sensed that the only important journey I would make henceforth would be journeys out of time and into mind. There was another landscape to be discovered and negotiated. The landscape of the heart, the emotions, and the imagination had to be opened up and new route maps plotted ... We talked late into the night arguing whether or not we, too, have journeys mapped on our central nervous systems. It seemed the only way to account for our insane restlessness."

So how could I now account for my own restlessness and my insistence on travelling to Alaska? It seemed to stand in contradiction to my deeply felt resolve at the conclusion of my South American travels. If I had determined that the only journeys I would make should be into the imagination and the landscape of the heart, then why was I thinking again of the Alaskan wilderness? For it was more than an old man's romantic folly, if not best forgotten then consigned to wishful thinking. The idea of an undiscovered country set in an elemental landscape fascinated me. It appealed to my anarchistic notions of boundless freedom. Sure it was romantic, but it was also real. Alaska was not a figment of my imagination. It existed in time and in place, and in my mind as somewhere that might test my self-assurance. One thing was for sure: it was clearly written on the map of my central nervous system.

It's a long way from Avoniel Road, where I went to school, to Alaska, where I dreamed of going, and the distance is in more than miles and physical geography. After all, what correspondence could there be between Belfast in the north of Ireland and Barrow in the far north of the Arctic Circle? But Avoniel primary school in east Belfast gouges itself up out of my memory as an original point of departure. It was 1959, and I was approaching my tenth birthday. I was a "good child", as my mother described me, quiet and untroublesome.

The school was a big, two-storey barracks of a building, solid and imposing, set among the maze of back streets it served. A great lawn of two junior-sized football pitches stretched out in front of it. To the right and screened from the entrance was a concrete netball pitch, and beside that the boys' and girls' outside toilets. Whatever advantage the 1947 Education Act had provided for the children of the area it did not accommodate indoor plumbing. But then this was the catchment area of the aircraft factory and the shipyard, and me and my mates were all cannon fodder for the engineering industry. The football pitches were the largest green space in the area but they were forbidden to any of us after school hours. I was not of an athletic disposition anyway, and though I occasionally scaled the railings during the summer holidays it was more because the place was forbidden than out of any desire to kick a football.

I compensated for my lack of sporting skills by finding a refuge in books. I excelled at reading and had finished all the "readers" we were required to make our way through long before my peers. If I was always the last kid picked to play, I was equally the first to complete any reading tasks, and I had more gold stars than anyone in my class. My special reward for being so far in advance of the rest of my classmates happened the day my teacher called me aside and suggested I might like to choose a book from the library. The library in Avoniel was an old Welsh dresser with locked doors stationed at the end of the first-floor corridor. It was also where the classrooms for the kids about to go to the "Big" school were located, and the library was exclusively for their use. The upper shelves were full with about three dozen books. I remember being quite frightened as my teacher walked me out of the class, admonishing the rest of the kids to be quiet and get on with their work until we returned. Whatever alienation I had felt from the rest of my mates, it was now compounded by this "honour". I was nine at the time and should not have been using the library for another year or two.

Standing on the rickety chair scanning the book spines in front of me, I felt like a sacrifice; these books were teeth in the great God monster that was going to devour me.

"You pick one, sir," I said, immobilized and wanting to be away from this looming altar of words.

The teacher laid his hand on my shoulder and in a voice that conveyed neither sympathy nor enthusiasm pronounced, "No, young man, you're going to read it, so you choose it."

I had never felt so alone in my life. Again I scanned the books before me. Their titles were just a jumble of words that meant little to me and only added to my confusion. Then my eyes alighted on one book; the four words comprising its title were easy for my young mind to read. The conjunction of the words were intriguing and the stark image on the dust cover of a large dog howling into a richly coloured sky impressed itself upon me. I picked it out, climbed down from the chair and handed the book in silence to the teacher.

He took it from me and announced the title to the empty corridor: "The Call of the Wild." He smiled thinly and continued, "So, you like dogs, do you?"

I answered him automatically, the words spilling from me. "Yes, sir. My dog at home is called Rex!"

His smile hung there for another moment, then he said, "It may be a little difficult for you, Keenan, but it is a great adventure story. Try it, and we'll see how it goes." I held out my hand to take the book. "I'll bring the chair and you bring your dog!" he added, handing me the book.

For more than forty years I have had that dog with me, and the call of the wild echoes in me still. The story of Buck has, it seems, permeated the whole of my growing up, and here I am in my fifties still enraptured with it, the author and the landscape that gave it birth. The Call of the Wild is a parable about surviving and overcoming against all odds. It is about struggle and fulfilment, and it is ultimately about becoming what is in one to become. The call of Alaska's wilderness became a siren song; to resist it was to smother a vital instinct in myself. Maybe mortality and old age were knocking on my door and maybe I was not ready to let them in. There was another place I needed to go first. The last sentence of The Call of the Wild still speaks profoundly to me about the mystery and magic of that place, and about the torment of the author who wrote so eloquently about it: "When the long winter night comes and the wolves follow their meat in the lower valleys he may be seen running at the head of the pack through the pale moon light on glimmering borealis, leaping gigantic above his fellows, his great throat a bellow as he sings the song to the younger world, which is the song of the pack."

Still, I don't know if it was my solitary childhood immersion in Jack London's barbaric Northland that created my yearning. Isolated and barren landscapes draw me to themselves, different places for different reasons, but the one constancy is the lure of emptiness and wilderness. I suppose I feel comfortable there, untroubled. I can imagine a recreated life, and I confess a part of me is a loner. Loneliness, isolation and empty spaces are, I suppose, the preconditions of the dreamer, and I am a dreamer, unreconstructed and uncompromising. I pursue the landscape of the imagination and seek to find in the world about me some correspondence between the external and inner worlds, or perhaps a trigger for their coming together.

All journeys for me have this dual nature. But Alaska is no dreamland. It is raw, wild, primordial and uncompromising. Forsaking the holy grail of the imagination and emotion for a Klondike chronicle might be more demanding of the traveller than I could conceive. But only when you really contemplate it do you begin to slowly comprehend that Alaska is as complex as it is large.

For a start, it comprises several time zones and climatic regions. There are a minuscule number of roads for a region larger than England, France, Germany, Italy, Holland and Ireland put together. Negotiating such a vast expanse would be a nightmare of logistics, and as I intended to take my family with me I was multiplying my problems fourfold. But there was no way I could leave them behind. Maybe I was afraid the emptiness might engulf me, but my intoxication with the call of the wild was spilling over into my family life. I wanted to take my sons to see the place that had embedded itself in me when I was a child.

One belief I hold as an absolute truth is that the mind forgets nothing. I might forget things, but my mind forgets nothing. My sons were younger than I was when I was first smitten with Alaska. They might not enjoy months of living like the Swiss Family Robinson in the wilderness. I might not myself. Perhaps the illusion would evaporate there. Perhaps I had made too big an investment from my childhood in this imagined land. But that would be for me to resolve. Even if in the years to come my sons forgot their stay in Alaska, they would still have it stored in their memory bank to revisit over time, as I had done on many occasions. I only wanted to reveal to them the place that had continued to inspire me. I wanted Alaska to be more than their old man's ramblings. It could become for them whatever they chose. They only needed the seeds planted in them by exposure to the place, just as they had been implanted in me by exposure to Jack London's calling wilderness.

But there was another curious incident that swept the winds of Alaska right into my home and made my visit an imperative. I had visited Fairbanks in central Alaska several years earlier as a guest lecturer. My stay was brief and confined to the environs of Fairbanks and its university, but it was enough to seal my long-held fascination with the place. While there I spoke with a group of students and some members of the public who attended my lecture as non-registered students about the use of the "instinct" in the creative process. I happened to mention that I had a notion to write a book about a blind musician, and as I knew nothing about music and was not blind I hoped my instinctual facilities were in good order.

I soon forgot the incident, but was brought sharply back to it while in the process of writing the book. I had spent years researching my subject and was tortuously trying to put the fiction together: I was finding it hard going trying to imagine the life of an eighteenth-century blind harpist, Turlough Carolan. Several months into the task I was about to give up and forget the project, though it remained very close to my heart. I was locked in one of those imaginative and intellectual culs-de-sac and was beginning to question the validity of what I was writing about. The whole thing seemed pointless.

At the very time I was contemplating this, I received a letter with a Fairbanks postmark. The letter was brief with no return address, the handwriting tiny but neat. It looked and felt feminine to me but I could not make out the signature. It informed me that its author was aware I had intended writing a book about Turlough Carolan, who was a "Dreamwalker". The word threw me totally. I had not come across it before and never in reference to my subject. Mainly due to frustration with the lack of empathetic engagement with my subject, I dismissed the letter as having been written by some demented old spinster in the Alaskan outback who filled her days by writing strange letters to complete strangers.

I persevered with the book, stumbling into blind alleys and raging out of them. I wanted to get inside the emotional and psychological persona of the man I was writing about, but the fact that I wasn't blind combined with a marked musical illiteracy was making the book impossible. After months of struggle I finally came to the conclusion that I should jettison the project. Though I had promised myself for years that I would write the story of Turlough, I felt I had come to the end of the road.

Then another letter with an Alaskan postmark arrived, again with no return address, the same female handwriting and the same obscure signature. This time the letter was less brief, but the word "Dreamwalker" was back on the page and intriguingly there was an explanation of the term. I no longer have the letter, nor do I remember the exact words, but the imprint of it remains with me. Briefly, it related that the "Dreamwalker", whoever that may be (in my case Turlough), comes to visit people in their dreams. Their purpose is to give something, usually something healing and usually something that has to be passed on.

For some reason the letter seemed to take hold of me. I read it over and over again, then paced the floor trying to come to terms with the information and its relation to my work. I meticulously tried to decipher the signature and thought I could make out an Inuit name. But I could not be sure. The timing and the content of her letters seemed otherworldly. What was this strange Inuit woman from somewhere in Alaska trying to tell me? Why were her "Dreamwalker" letters always arriving at the precise moments of creative crises in my life? What was the connection between her and my long-dead blind musician? And what was my part in the weird triangle? I thought about it over and over again. It was like trying to work out some unearthly trigonometry.

Then, from God knows where, it hit me like a slap in the face. My torpor lifted and I was shown the way out of my dilemma. If my eighteenth-century itinerant musician had walked intomy dreams then I need only walk in his. In writing out his blind dreams I could convey his psychic and emotional life, thus extrapolating out of the man himself how he lived, how he composed the music he did, and why.

I finished the book with my muse from Alaska driving and directing the story. Sometimes I look at it on the bookshelf in my study and think how it would not be there, indeed how it would not exist in any form, had I not received those mysterious letters from the Alaskan wilderness. I had rid myself of my eighteenth-century musician but a new and more prescient Alaska was calling to me with irresistible attraction. It had now given itself a voice that was separate from my own fantasizing. So I chose to return with a head full of questions about that inspiring landscape and the primitive animism that exists there.

Jack London once wrote in a letter, "When a man journeys into a far country, he must be prepared to forget many things he has learned, he must abandon the old ideals and the old gods and often times he must reverse the very codes by which his conduct has hitherto been shaped." There was something in those words of London's that excited my imagination about my mysterious pen friend, and the magic that connected us. She was not just some figment of my frustrated imagination, she was real and living out there in the boundless wilderness. Her communications had moved psychic mountains for me, and the acknowledgement on the flyleaf of the book hardly seemed sufficient reward. But could I find her in that huge country? If I was to accept London's words, what would I have to abandon, and what reverses would I have to make? For a moment I thought of Joseph Conrad's failed heroes who are devoured by the landscape they enter, and I recoiled at the journey that was beckoning me.

I thought again of London and the struggles of his heroes, men and dogs, against the forces of nature and one another. His stories embody a recognition of primal forces that can transform or crush people, at the same time hinting at something in the personality of their author, an illegitimate child whose poverty-stricken childhood taught him how to fight to survive. Like myself, the author would take himself off on small voyages of discovery, surviving on his wits and animal cunning. As a man, he was strongly influenced by Marx, Hegel, Spencer, Darwin and Nietzsche, from whose works he evolved a belief in humanism and socialism and an admiration for courage and individual heroism. I was drawn to this complex, tragic man. A writer who wrote in the naturalist tradition of Kipling and Stevenson. A Marxist who flirted with dangerous notions of the superhero. A socialist who argued against the Mexican Revolution. But, ultimately, a man who drew his own map in life. In many respects London was like one of his strongest characters. In The Sea Wolf (1904), Wolf Larsen is the incredibly brutal but learned captain of the Ghost who is doomed by his individualism. The central character of Mark Eden was also ominously autobiographical, not only telling of an ex-sailor who becomes a writer but also of the emotional turmoil, the loss of identity and selfhood and ultimate suicide. Maybe the author's idealism was too highly pitched. He was shipwrecked by failed marriages, bankruptcy, alcoholism and suicide. Obviously there had been some dark, self-destructive alter ego that would not allow the man to "reverse the very codes by which his conduct has hitherto been shaped". He certainly had much to say about fear. He considered it mankind's basic emotion, a kind of primordial first principle that affects us all. But understood in the right way, fear need not be a harness. London's protagonists challenged it, even chose at times to forget it. Fear was a prime motivator for London the man, too: it made him shake off the shackles of conformity and achieve success.

"There is an ecstasy that marks the summit of life, and beyond which life cannot rise," he once said. I had unknowingly tasted that ecstasy as a child with my face buried in the author's epic in a tiny two-up-two-down family home whose confines smothered me. In the Belfast back streets where the only green space was locked away from me behind iron railings I drank deeply from London's elixir and its taste stayed in my mouth. Foolishly or not, when I was younger I was a man who was afraid of being afraid. It forced me to make choices and flooded me with questions I felt only the Northland itself could answer. But I was older now and hopefully a little wiser. Maybe I was tired of being afraid of being afraid. If I was to "forget many things .". . abandon the old ideals and the old gods . . . and reverse the very codes that had formed me then perhaps I could only fully reclaim this lost part of myself during a wilderness experience.

Was Alaska still peopled with those quirky, eccentric and reclusive individuals that made Robert Service famous and fascinated London? Service's rhythmic and zestful poems about the rugged life of the Yukon were also part of my growing up. "The Shooting of Dan McGrew" and "The Cremation of Sam McGee" were in every school anthology and brought the Canadian outback into our mundane school days. Alaska was called the "Final Frontier" before the writers of Star Trek hijacked the phrase, and I wondered if it still had the same kind of allure for people as it had for its most famous writers. What impels people towards finality and the last place on earth, and what do they resolve there? Why do they stay in the seemingly inhospitable land? Have they a perverse sense of beauty akin to my own? If so, how do they understand it? These were my questions, and neither London nor Service could answer for me.

Maybe the Final Frontier is an inaccurate description, for assuredly Alaska is the Frontier of Fable. The onion-domed churches of nineteenth-century Russian Orthodoxy still break up the skyline around Juneau, Sitka and Kodiak. Further north the Inuit peoples cling to their religious beliefs with their shamanism and an animistic respect for the natural world from which we all could learn much. And everywhere one still finds those curious, rugged, idealistic individuals who have washed up in this vastness, and perhaps it's the proper place for them, for here the emptiness is big enough to contain their madness. Only a place as immense as Alaska can properly contain a fevered imagination. This is the land that Swift, C. S. Lewis and Tolkien never discovered, as fantastical as a fairy-tale but undersewn with deep soul-searching.

I began to pore over maps of Alaska. But any map of Alaska is a Spartan illustration: railway lines and road systems are conspicuous by their absence and Juneau, the state capital, is accessible only by air and sea. The state is more easily measured in time zones than miles. It contains four such zones and a total population of just over 600,000, half of whom reside in Anchorage, Alaska's largest town and port; the rest of the population is spread out across this massive, seemingly endless state in communities that make the map look more like a join-the-dots picture such as you find in children's colouring books. But this is no childhood fantasy land. The incomprehensible hugeness of the place is something to be wary of. I remember a friend I had met during my first brief visit to Alaska saying, "Be careful when you're reading maps in Alaska. Names don't always mean places and named places don't always guarantee that people live there. There are some communities in Alaska where people live so far from one another that they are all but invisible. That kind of landscape doesn't only make you feel small, it can be very scary and very dangerous too."

I thought over my friend's words as I scanned the place names spread out before me. The Inuit names scattered around the margins of the landmass were curious and almost unpronounceable; my tongue tripped over glottal stops as I tried to say them: Unalakleet, Koyukok, Umiat, Shungnak and Shageluk, Akhiok, Ekwok, Quinhaqak, Togiak and Yakutat. Then the curious European names that marked the commercial expansion — and settlement: Russian Mission and Holy Cross, Valdez and Cordova, and the place names of the miners who had come in droves, desperately poor, dream-driven men whose rudimentary education made them believe their dreams and give names to places the way you would throw scraps to a dog. The names were simple, yet just reading them brought you very close to their world: Livengood, Sourdough, Chicken, Coldfoot, Eureka. Then there were the mountains, from Mount McKinley, the highest on the continent, to the permanently frozen Brooks Range, the most northerly. The Koskokwim mountains and the Wrangell mountains, and more mountains — the St Elias, the Kilbruck, the Taylor, the Talkeetna, the Asklun, the Romanof, the Shublik — and then the great ranges, the Aleutian and the Alaskan. There were yet more mountains that no-one had bothered to name because no human had ever set foot on them or ever wanted to. Obviously there were some places that refused admission to the human species.

But however brutal, imposing and empty, people had chosen to go there, and to stay. Most assuredly Alaska is not a place one simply stumbles upon. Even in the book of choices this forbidden, inhospitable emptiness would hardly rate in the top twenty of anyone's most desirable places to settle in. Yet native peoples make up only about 20 per cent of the population; the rest are immigrants, or perhaps more correctly self-inflicted exiles. Who were they? Why had they come? What were they running from? And, more importantly, what had they found? How the place had transformed them to make them stay was what I wanted to know. Was there really some kind of magic here, or had the stone-cold landscape frozen their souls and immobilized them? For after Alaska there are no more choices, no more places to go. It is, after all, the Final Frontier.

Poring over maps doesn’t answer questions, it only adds to them, and in the case of Alaska it only served to deepen the enigma of the place and my resolve to return. I was determined that my journey should take me through the four geographical quarters. First, the coastal south-east and the south-central region to hunt down Jack London's first footfalls; then south-west and the Bering Sea coast; then into that light-filled, enclosed world of the Arctic region; and finally into the interior, ranging out from Fairbanks on small voyages of discovery or displacement. I intended travelling only during the period of maximum light, from snowmelt in mid-May to snowfall in mid-September, for I have had more than my share of dark places, and anyway, Alaskan winters are not made for travelling great distances.

As I began to plan the logistics of trying to encompass this vast land, I was ever mindful of Jack London's advice about his Alaskan experience: "It was in the Klondike I found myself. There nobody talks, everybody thinks. You get your perspective. I got mine." I remembered too the author's imperative about being prepared to forget and abandon many things, and concluded it would be impossible and a serious error for me to try to work out a detailed schedule and timetable. The country was too big to be reduced to a precociously planned itinerary. If any journey was simply a record in time of passage between two points then few of us would need to make such journeys; we could simply read the records of others. Rather, a journey is like a work in progress: you extract meaning and insight from the experience.

Alaska was calling me out to its wilderness. Would I be equal to it or would it be unequal to my dreams? There was only one way to find out.

Packing was a nightmare; the problem was as big as the landmass I was venturing into. How does one wind- and weatherproof two adults and two children against climatic conditions that vary between Arctic numb and Mediterranean wet, occasionally bleaching into the high hot days of an Indian summer? I looked at the bags piling up: they too were mocking me. It would take a brigade of army engineers to move this lot or at least a string of pack mules. I intended travelling a lot and the idea of constant packing and unpacking was already defeating me.

I thought it through over and over again. Four time zones,climatic conditions so varied that nothing could be depended on. A road system, in a land of continental dimensions, that amounted to a few hundred miles rather than thousands of miles. I would have to fly long distances in tiny light aircraft, and those that know me know that my fear of heights is legendary. Also I cannot swim and much of the south-east and south-west peninsulas can only be explored by small boat. I was certainly no Grizzly Adams and the logistics of my fanciful expeditions seemed to be impossible. It was like a logarithmic problem that had its resolution somewhere in infinity, and that, seemingly, was where I was going too.

In an attempt to reassure myself and to keep my worst fears from my wife and family, I turned again to my mentor Jack London and considered how he would have handled all this. In a letter to one of his friends he writes of his first encounter with the infamous man-killing Chilkoot trail, which had to be negotiated to enter into that wildness that so fascinated the author and myself.

"The sands of Dyea resemble an invasion beach. Everywhere men bartered with Indian porters, trying to persuade them to haul their food at reasonable prices. Jack's ageing partner Shepard took one look at the glittering white wall of the Chilkoot Pass and decided to turn back. Within weeks, he would be joined by thousands more. In retreat, they would find abandoned kit littering the coastline for forty miles." Despite the Chilkoot Pass's back-breaking nature, by the autumn of 1897 twenty-two thousand men and women had reached the other side. Jack was among them. But only after a struggle which tested his stamina to the limit.

Crippled horses littered the trail, "broken-boned, drowning, abandoned by man". They died "like mosquitoes in the frost. They snapped their legs in the crevices and broke their backs falling backwards on their packs; in the sloughs they sank from sight or smothered in the same, men shot them, worked them to death and when they were gone, went back to the beach and brought more. Some did not bother to shoot them, stripping the saddles off, and leaving them where they fell. Their hearts turned to stone, those which did not break, and they became beasts, the men on Dead Horse Trail."

I looked again at our mountain of luggage and the sparse map, mulling over all the what-ifs that were niggling at me. It seemed I was contemplating my own Chilkoot Pass without having set foot in Alaska. I certainly do not possess the same "will to power" that was so much part of London the man and the writer but I suppose I had a soul hunger akin to his, and if he could survive on that perhaps I could too.

However, no matter how I dealt with the difficulties, most of which were imagined, there were two real problems that would not go away. I was having sleepless nights about the smallest of the inhabitants of this land where everything was big, namely the mosquito and its near cousins the black fly and the suitably named "no-see-ums", whose bites are far more annoying precisely because you cannot see the creature.

Permafrost was another problem. Its constant presence just feet below the surface ensured that plumbing was more than a luxury. In many places it was impossible to install simply because it would never work. I did not dwell on this subject too much with Audrey, but simply explained that she should expect things to be very primitive in some places.

The mosquitoes eventually won out. My Alaskan friend Pat Walsh had warned us not to underestimate their number or their size. To emphasize her point, she sent me a miniature penknife, no more than an inch long, with one small double-sided blade like a paring knife. When I thanked her and queried the purpose of such an ornament she answered curtly: "It's not an ornament, it's for skinning mosquitoes!" I decided to change the order of my travels, visiting "the Bush" first, before the insects got too thick on the ground, then moving on to the Bering Sea coast and the south-east and south-west peninsular regions, where my expectation was that the open space and coastal winds would keep the bugs at bay.

Trying to solve problems before you encounter them is frequently a wise precaution but it can also be a debilitating one. Having convinced myself that it was better to confront the enemy in his own back yard, we headed north to the last frontier, come what may!

Recenzii

“Wonderfully evocative and at times quite extraordinarily moving. There are many moments you carry with you long after you’ve turned the last page. Magic.” —Sunday Tribune (London)

“An excellent travelogue . . . full of one-off characters vividly brought to life . . . an engaging and articulate book that does much to illuminate America’s Last Frontier.”

—Daily Telegraph (London)

BRIAN KEENAN is the author of An Evil Cradling, his classic account of his years as a hostage in Beirut. He lives in Ireland.

“An excellent travelogue . . . full of one-off characters vividly brought to life . . . an engaging and articulate book that does much to illuminate America’s Last Frontier.”

—Daily Telegraph (London)

BRIAN KEENAN is the author of An Evil Cradling, his classic account of his years as a hostage in Beirut. He lives in Ireland.

Descriere

In the course of a journey that takes him through four geographical quarters from snowmelt in May to snowfall in September, Keenan discovers a land as fantastical as a fairytale but whose vastness has a very peculiar type of allure.