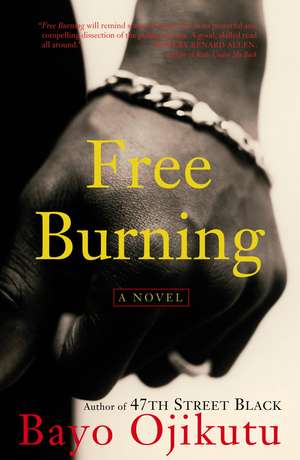

Free Burning

Autor Bayo Ojikutuen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2006

Soon Tommie is laid off, and he begins to see himself as just another faceless entity on the city’s fringes. After each fruitless job interview, Tommie’s wife withdraws from him further, and in the mirror he faces

the reflection of failure his family never intended for him. Stymied by rejection and mounting debt, Tommie is seduced into peddling dope as his best opportunity to define himself and to provide for those he loves.

But a corporate job is no preparation for hustling, and when Tommie finds himself on the wrong side of a crooked cop, everyone wants a piece of him: his street-hustling cousins, the police, friends, loan sharks, even

a panderer from his white-collar past. In order to break free, Tommie must find a way to dig himself out of a deepening hole, before the city buries him.

Preț: 90.38 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 136

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.29€ • 18.49$ • 14.42£

17.29€ • 18.49$ • 14.42£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400082896

ISBN-10: 1400082897

Pagini: 383

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 1400082897

Pagini: 383

Dimensiuni: 133 x 204 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

BAYO OJIKUTU is the author of 47th Street Black, winner of the Washington Prize for Fiction and the Great American Book Contest. He currently teaches in the department of English at DePaul University. Ojikutu was born and raised in Chicago, where he still lives.

Extras

1

Cousin Remi lives on the corner, right before the lake floats away from the city. He rents this narrow crib with three stories stacked to the sky and cracked siding chipped from its frame after all these years fighting wind blown off South Shore Drive.

The place isn't the last on the corner anymore, hasn't been for a year now. I forget the red-and-beige flat built on top of the empty hangout lot where east-west numbers met north-south names. This new tower with the spiked black iron gates protecting its owners from the street crossing, and full Christmas-tree-green grass growing inside the iron. Its lawn is so long and thick seen up against my cousin's half-dead stubble colored like hay and old money. A brick terrace juts out of the third-story front with one to match on the backside, more iron gating both, and a satellite dish spins from the roof to beam in Jesus Christ and J.Lo and young Julio Iglesias, and all such kinds of holy noise, to these red-brick curbside folk.

Now there's another tower built just like the first on the south side of Remi's place, on top of what was once a boarded two-story. Back when Cousin's place was still the last on this side of the block, I could see the shacks coming from east or west on 78th, standing up narrow and haunted and higher than everything else along these rows. These funky new towers cast shadows over the Four Corners today.

These young Mexicans bought the curbside tower to the north. No Latin would even think of crossing north of 79th Street on foot near the lake when we were boys, much less living on these corners. That's not even speaking of the Naperville whites living one tower further south now. We don't see either of them much--we watched as they landed with their big green Mayflower and white Ryder trucks--but they don't bother with the block these days. Just ride in from places far off come evening time, shut their doors and wait for the sun to rise and for us to disappear. Then, come morning time, they start their journey all over again.

I'm almost at Phillips Avenue when I blink and slide the Escort in reverse, wheel into the spot between Remi's place and the south tower. The city fixed handicap signs to mark this space six months back--but I don't care. There's been a blind brown-and-gray woman living right across this street, long as my cousin's been here at least, old lady with two orphan grandkids as gimp-eyed as her. But nobody ever thought about posting caution signs until these people came and raised towers and moved in folks who claim a child with autism just so they can hold a spot out front for the Lexi. When I stop by Remi's these days, I park between the city signs and curse them- "Fucking boo-jie jokesters," I say, "fuck um," out loud. Repeat it every time, just so I remember.

"How long you been here? Ain't hear you knock." We're blood on my mother's side, as Remi's the one child Auntie Denise had before the IC train took her on home. Only male family I've ever known who didn't come from a gangway or the sidewalk corner, or an assembly line; and if he did come from those places, at least he's the only one who stayed. His computer screen flickers gray and white light against tree bark skin. "Shit, close the door."

"Let myself in," I say and shake the key ring in my right fist. "You mind, huh? Busy or something?"

Remi hasn't spun his chair from the monitor. He speaks to the light juking across his screen instead. "Busy for you, cuz? For some other trifling somebody, yeah, I'm busy. But for your trifling ass? Never. Close the door all the way."

He clicks the mouse. "Ain't nobody else here, Rem. Don't sound like it, no ways."

"Your reflection's all on my screen," he says, "and they'll be back."

Silver-framed pictures line Remi's office. The cracked plaster just behind the desktop is covered by Johnnie Coleman preaching about sins dancing down in hell and clouds testifying up in heaven, Billie Holliday singing tears full of blue heron and blood, and Madame CJ Walker burning the naps out of Harlem heads. Near the window, Mahalia Jackson casts alleluia spells and Lena Horne looks all creamy in some flick from the old days and the Joyner girl (not the one with the nails and hair, the other) runs away from herself because she's all that's left to leave. Behind us, Cassius Clay drops Liston in honor of Elijah and Muhammad, letting the world know it'd be best to go on and call him "Ali" proper. Then my man Rich Pryor spills his illness from the stage until all pain and joy leave him numbed by laughter. Just before the wall's end, Mayor Harold breaks the wheels off the city machine- not the real, blue worldwide machine, just this little pissant Chicago version- and Malcolm spouts city rage from up high at the old mosque.

Right before these walls meet to finish the room in cobwebbed corners, Dizzy blows his horn across the way to Josephine half-naked dancing the juke jive. In this computer monitor's flicker, I catch Dizzy's notes floating about, switching her straw-covered hips left and right and bouncing bebop back over our heads.

"Where they at?" I ask and Remi looks over his shoulder at me finally, still without turning his chair.

"Don't know," he says through teeth clenching against bottom lip. "Out on the blocks, I guess. You know how high them niggas be when they come back from hustling."

My cousin's computer screen and these pictures framed cheap to hang from the wall, a dim bulb lamp, the swivel rocker at his desk, two folding chairs, and a phone wire stretching from the back of the desk are all that decorate the room.

"Been at the Soft Steppin?" I see his question in gray and white slipping its way through Dizzy's notes and Josephine's jungle love.

"Where else?"

Remi taps the mouse to the horn blower's time. "Ain't your lady home waiting on you?"

"Not ready to go home yet. Hell, you know what time it is- past one o'clock. Ta's been at work all day. Knocked out by now, been so. She ain't thinking nothing bout my ass."

"Mmh." I hear that sound forced through his throat, and I know the reason behind his questions. Remi wouldn't care about a damn thing but the dungeons, dragons, and white knights flashing across his screen right now if my wife hadn't called over here to track me down. Been with her six years now, and known him all my life- figuring the workings of their riddles is my second nature by now. Tarsha calls Remi to scream when she hurts to be heard, because my cousin was born with these ears, big, soft, and kind. She carries on until her yells turn into weary whimpering words forced through quivering lips and punctuated by a row of sniffles:

"You're the only one who can talk sense to him, Rem," all juiced up and begging, she cries. What was left for my cousin to do but promise to come to the rescue of a poor, thick Oglesby Avenue honey, like a good white knight should? She's my wife, mother of my baby girl, and he's my boy, my cousin and my boy, but tears and thighs still talk to the blue and black soul, blood or no blood.

"Got any bites yet?"

"Shit, market's dry now, Rem, you know it. Look at the news. Read it." This's the same script I offer Tarsha on her Sundays off. "Shit's hard in the square hustle. Only those fucking kings on their hill got it easy now."

"Ain't gotta prove it to me." Remi's medieval conqueror dies on-screen and the flicker stops. He turns from the monitor and pulls the lamp chain until these walls fill with stinging light. I can't see Dizzy and Josephine doing their thing now. "When hypes quit spending loot for the herb cause they're paying it all out for rocks and blows over in Englewood and the stash is so short I gotta use off-brand chicken seasoning to pack my last dime, I know times is hard."

"Thought there was no recessions in the game?"

"Muthafuckin kings, you said it." Remi lights a Newport from his T-shirt pocket. "Went and dicked up the Taliban, so that Afghanistan poppy blows down from those hills to sell cheap off Sixty-third Street. Pure as I don't know what. Kings all getting their cut."

"What time Tarsha call?" I take a smoke from the carton Remi offers, and my laugh floats through dust.

"Ain't talked to her since last week." He lights my cigarette and the flame blocks me from catching the lie in his eyes. Not that I would've seen it anyways- Remi's so smooth, his tales spin circles around his own knowing. The valleys of his cheeks squeeze tight at his mouth to stop the truth from squeezing through, leaving the reaching point of his nose the only limb that gives up the tale. Just that nose and the dark skin crawling on bone around his eyes.

"We're holding up tight though. Her gig is solid downtown, for now. She's making enough to pay rent and keep heads floating. For now."

"You let me know." Remi blows smoke at the knight's bones.

I swallow and cough. "Still got the state check coming in, too, you know. Three more months riding on that for me still. It helps."

"Don't get me wrong. There's still money in this hustle," Remi explains to this hardwood dust. "I complain, and hypes do run to the hard dope these days. Desperate clowns. Enough to make a nigga think about putting cash in a ki, make some real paper. But that's a bloody way, messing with rocks and blow. Still cream to be made right here with the herb. Clean cream, cleaner than some at least. Ain't much blood to this hustle, and enough cash to keep the head on straight. You holler when you need help getting down, Tommie."

"I will," I tell Remi, "appreciations."

I hear Westside Jackie Lowe now, him and their latest housemate, whose name I never keep straight (James-Peter, Peter James, some such biblical founding father concoction). James-Peter is kin to Remi and Jackie somehow--but I don't claim him as my own true family, no more than I do Westside, no matter that I call them both "cousins." We've all got the same blood running in us somewhere, so even when we don't tag New Testament founders from the West Side as true blood, they're still our kin. Calling it out loud like that is the easy way to stop ourselves from getting confused about names and history and such.

Westside is Remi's younger brother by a few years. Same father, different mother. Some ho strolling honey from Madison Street and Independence Boulevard gave him birth. The fool was pushed from a Westside womb, though he's lived here in the Four Corners all his years. He and Remi are barely blood brothers themselves.

"Put that shit down," Jackie Lowe yells over the stomp of boots and gym shoes from their living room. "That's my shit. Yo punk ass ain't do shit for it. My . . . shit- how you gon come up in my house and take my shit after I did the work to get it? Who the fuck you think are you?"

"Fuck you," James-Peter answers. "'Yo crib?' Bitch-ass mark, so what I took your shit. You took the shit from somebody else. So what? Possession's ninety-nine percent, muthafucka."

"How much you want?" Jackie mumbles. "I want my bike back."

"Your bike? Dumb ass," James-Peter yells.

"How much?" Jackie pushes the office door and stabs his head into the private space. He is ruby red-skinned, the melting genes of slaves and Latin kings and Italians and house masters hopping and popping about above his eyebrows and under his cheeks.

He leans on the wall, so close to Dizzy that the jazz man's frame bends crooked against plaster. Westside puffs sweet, cheap leaves stuffed in blunt wrapping. "Oh, my main cuz, Tommie Simms? Didn't see your car out front."

"Handicapped spot."

"A dub," their housemate hustles on the other side of Mahalia's wall. "Give me a dub, you want your bike back, Jack. Now what?"

"A dub? I climbed on the back of that gate and up the porch to get the gawdamn thing in the first place. How you sound?" Jackie turns from his roommate's offer and points the blunt at me, and he giggles. "Told you bout parking there, Tommie. Told you they got a gimp living next door. Get your shit towed fast, boy. Them folk don't care nothing bout no bullshit, raggedy-ass Ford. Got a deal with the city on that spot."

"You're Richie's meter maid now?"

"Hell yeah. Just don't be parking your bullshit in fronta my crib, is all." Jackie laughs louder in his stinking clouds. "Hurts property value."

"I'm gone."

"All right then, Tommie. You ain't gotta go nowhere. Don't be so sensitive." He points at the back of Remi's head. "Chief, we got some skeezes from Seventy-ninth bout to come through, trying to get loose with the fellahs."

"Not from the motel?" Remi asks without looking at Westside. He clicks the mouse to protect this conqueror's new life.

"Naw, Rem-Dog. Ran cross these two at the bus stop off Cottage. Rolled up on um in your Rover. Fresh babes got to slobbering at the lip talking bout where 'y'all going to, who car's this, can we ride with y'all,' testifying on how down they wanna be. Course, I told them it was my boy's ride, and we couldn't get down with them unless they brung the get-down to him, right. They went to get another friend, then they'll be through the spot. Hehe- that's how smooth I am, Tommie. You wish you was playa-smooth like this here, don't you?"

"Yeah, I wish." I peek from Mahalia's shadows and the conqueror soon to be burned to ashes by this digital dragon. "Like you. Sure do."

"You told them it was my truck?" Remi's says.

"Of course I did, Rem-Dog. You my dog. Like how Snoop say it-"

"Right." Remi drops his square on the hardwood, squashes it with his shoe sole until ash simmers.

"Fresh babes," Jackie repeats as he steps out of that living room light. "Like eighteen, nineteen years old, no older than that. Just right. Even got a plump one coming for you, Tommie, if you wanna stay. Just like you like um. Had you in mind, Cuz, just in case. Better claim this one before James gets his greedies on her."

"Thick, that's what I like." My eyes swell from the blunt's burn. "Not plump- I like thick women."

"Well go home to your wife then, ungrateful, fatty freak muthafucka. Beggars can't be- punk bitch. We don't love these hos." Jackie sits under Lena, and his clouds turn her even creamier.

Cousin Remi lives on the corner, right before the lake floats away from the city. He rents this narrow crib with three stories stacked to the sky and cracked siding chipped from its frame after all these years fighting wind blown off South Shore Drive.

The place isn't the last on the corner anymore, hasn't been for a year now. I forget the red-and-beige flat built on top of the empty hangout lot where east-west numbers met north-south names. This new tower with the spiked black iron gates protecting its owners from the street crossing, and full Christmas-tree-green grass growing inside the iron. Its lawn is so long and thick seen up against my cousin's half-dead stubble colored like hay and old money. A brick terrace juts out of the third-story front with one to match on the backside, more iron gating both, and a satellite dish spins from the roof to beam in Jesus Christ and J.Lo and young Julio Iglesias, and all such kinds of holy noise, to these red-brick curbside folk.

Now there's another tower built just like the first on the south side of Remi's place, on top of what was once a boarded two-story. Back when Cousin's place was still the last on this side of the block, I could see the shacks coming from east or west on 78th, standing up narrow and haunted and higher than everything else along these rows. These funky new towers cast shadows over the Four Corners today.

These young Mexicans bought the curbside tower to the north. No Latin would even think of crossing north of 79th Street on foot near the lake when we were boys, much less living on these corners. That's not even speaking of the Naperville whites living one tower further south now. We don't see either of them much--we watched as they landed with their big green Mayflower and white Ryder trucks--but they don't bother with the block these days. Just ride in from places far off come evening time, shut their doors and wait for the sun to rise and for us to disappear. Then, come morning time, they start their journey all over again.

I'm almost at Phillips Avenue when I blink and slide the Escort in reverse, wheel into the spot between Remi's place and the south tower. The city fixed handicap signs to mark this space six months back--but I don't care. There's been a blind brown-and-gray woman living right across this street, long as my cousin's been here at least, old lady with two orphan grandkids as gimp-eyed as her. But nobody ever thought about posting caution signs until these people came and raised towers and moved in folks who claim a child with autism just so they can hold a spot out front for the Lexi. When I stop by Remi's these days, I park between the city signs and curse them- "Fucking boo-jie jokesters," I say, "fuck um," out loud. Repeat it every time, just so I remember.

"How long you been here? Ain't hear you knock." We're blood on my mother's side, as Remi's the one child Auntie Denise had before the IC train took her on home. Only male family I've ever known who didn't come from a gangway or the sidewalk corner, or an assembly line; and if he did come from those places, at least he's the only one who stayed. His computer screen flickers gray and white light against tree bark skin. "Shit, close the door."

"Let myself in," I say and shake the key ring in my right fist. "You mind, huh? Busy or something?"

Remi hasn't spun his chair from the monitor. He speaks to the light juking across his screen instead. "Busy for you, cuz? For some other trifling somebody, yeah, I'm busy. But for your trifling ass? Never. Close the door all the way."

He clicks the mouse. "Ain't nobody else here, Rem. Don't sound like it, no ways."

"Your reflection's all on my screen," he says, "and they'll be back."

Silver-framed pictures line Remi's office. The cracked plaster just behind the desktop is covered by Johnnie Coleman preaching about sins dancing down in hell and clouds testifying up in heaven, Billie Holliday singing tears full of blue heron and blood, and Madame CJ Walker burning the naps out of Harlem heads. Near the window, Mahalia Jackson casts alleluia spells and Lena Horne looks all creamy in some flick from the old days and the Joyner girl (not the one with the nails and hair, the other) runs away from herself because she's all that's left to leave. Behind us, Cassius Clay drops Liston in honor of Elijah and Muhammad, letting the world know it'd be best to go on and call him "Ali" proper. Then my man Rich Pryor spills his illness from the stage until all pain and joy leave him numbed by laughter. Just before the wall's end, Mayor Harold breaks the wheels off the city machine- not the real, blue worldwide machine, just this little pissant Chicago version- and Malcolm spouts city rage from up high at the old mosque.

Right before these walls meet to finish the room in cobwebbed corners, Dizzy blows his horn across the way to Josephine half-naked dancing the juke jive. In this computer monitor's flicker, I catch Dizzy's notes floating about, switching her straw-covered hips left and right and bouncing bebop back over our heads.

"Where they at?" I ask and Remi looks over his shoulder at me finally, still without turning his chair.

"Don't know," he says through teeth clenching against bottom lip. "Out on the blocks, I guess. You know how high them niggas be when they come back from hustling."

My cousin's computer screen and these pictures framed cheap to hang from the wall, a dim bulb lamp, the swivel rocker at his desk, two folding chairs, and a phone wire stretching from the back of the desk are all that decorate the room.

"Been at the Soft Steppin?" I see his question in gray and white slipping its way through Dizzy's notes and Josephine's jungle love.

"Where else?"

Remi taps the mouse to the horn blower's time. "Ain't your lady home waiting on you?"

"Not ready to go home yet. Hell, you know what time it is- past one o'clock. Ta's been at work all day. Knocked out by now, been so. She ain't thinking nothing bout my ass."

"Mmh." I hear that sound forced through his throat, and I know the reason behind his questions. Remi wouldn't care about a damn thing but the dungeons, dragons, and white knights flashing across his screen right now if my wife hadn't called over here to track me down. Been with her six years now, and known him all my life- figuring the workings of their riddles is my second nature by now. Tarsha calls Remi to scream when she hurts to be heard, because my cousin was born with these ears, big, soft, and kind. She carries on until her yells turn into weary whimpering words forced through quivering lips and punctuated by a row of sniffles:

"You're the only one who can talk sense to him, Rem," all juiced up and begging, she cries. What was left for my cousin to do but promise to come to the rescue of a poor, thick Oglesby Avenue honey, like a good white knight should? She's my wife, mother of my baby girl, and he's my boy, my cousin and my boy, but tears and thighs still talk to the blue and black soul, blood or no blood.

"Got any bites yet?"

"Shit, market's dry now, Rem, you know it. Look at the news. Read it." This's the same script I offer Tarsha on her Sundays off. "Shit's hard in the square hustle. Only those fucking kings on their hill got it easy now."

"Ain't gotta prove it to me." Remi's medieval conqueror dies on-screen and the flicker stops. He turns from the monitor and pulls the lamp chain until these walls fill with stinging light. I can't see Dizzy and Josephine doing their thing now. "When hypes quit spending loot for the herb cause they're paying it all out for rocks and blows over in Englewood and the stash is so short I gotta use off-brand chicken seasoning to pack my last dime, I know times is hard."

"Thought there was no recessions in the game?"

"Muthafuckin kings, you said it." Remi lights a Newport from his T-shirt pocket. "Went and dicked up the Taliban, so that Afghanistan poppy blows down from those hills to sell cheap off Sixty-third Street. Pure as I don't know what. Kings all getting their cut."

"What time Tarsha call?" I take a smoke from the carton Remi offers, and my laugh floats through dust.

"Ain't talked to her since last week." He lights my cigarette and the flame blocks me from catching the lie in his eyes. Not that I would've seen it anyways- Remi's so smooth, his tales spin circles around his own knowing. The valleys of his cheeks squeeze tight at his mouth to stop the truth from squeezing through, leaving the reaching point of his nose the only limb that gives up the tale. Just that nose and the dark skin crawling on bone around his eyes.

"We're holding up tight though. Her gig is solid downtown, for now. She's making enough to pay rent and keep heads floating. For now."

"You let me know." Remi blows smoke at the knight's bones.

I swallow and cough. "Still got the state check coming in, too, you know. Three more months riding on that for me still. It helps."

"Don't get me wrong. There's still money in this hustle," Remi explains to this hardwood dust. "I complain, and hypes do run to the hard dope these days. Desperate clowns. Enough to make a nigga think about putting cash in a ki, make some real paper. But that's a bloody way, messing with rocks and blow. Still cream to be made right here with the herb. Clean cream, cleaner than some at least. Ain't much blood to this hustle, and enough cash to keep the head on straight. You holler when you need help getting down, Tommie."

"I will," I tell Remi, "appreciations."

I hear Westside Jackie Lowe now, him and their latest housemate, whose name I never keep straight (James-Peter, Peter James, some such biblical founding father concoction). James-Peter is kin to Remi and Jackie somehow--but I don't claim him as my own true family, no more than I do Westside, no matter that I call them both "cousins." We've all got the same blood running in us somewhere, so even when we don't tag New Testament founders from the West Side as true blood, they're still our kin. Calling it out loud like that is the easy way to stop ourselves from getting confused about names and history and such.

Westside is Remi's younger brother by a few years. Same father, different mother. Some ho strolling honey from Madison Street and Independence Boulevard gave him birth. The fool was pushed from a Westside womb, though he's lived here in the Four Corners all his years. He and Remi are barely blood brothers themselves.

"Put that shit down," Jackie Lowe yells over the stomp of boots and gym shoes from their living room. "That's my shit. Yo punk ass ain't do shit for it. My . . . shit- how you gon come up in my house and take my shit after I did the work to get it? Who the fuck you think are you?"

"Fuck you," James-Peter answers. "'Yo crib?' Bitch-ass mark, so what I took your shit. You took the shit from somebody else. So what? Possession's ninety-nine percent, muthafucka."

"How much you want?" Jackie mumbles. "I want my bike back."

"Your bike? Dumb ass," James-Peter yells.

"How much?" Jackie pushes the office door and stabs his head into the private space. He is ruby red-skinned, the melting genes of slaves and Latin kings and Italians and house masters hopping and popping about above his eyebrows and under his cheeks.

He leans on the wall, so close to Dizzy that the jazz man's frame bends crooked against plaster. Westside puffs sweet, cheap leaves stuffed in blunt wrapping. "Oh, my main cuz, Tommie Simms? Didn't see your car out front."

"Handicapped spot."

"A dub," their housemate hustles on the other side of Mahalia's wall. "Give me a dub, you want your bike back, Jack. Now what?"

"A dub? I climbed on the back of that gate and up the porch to get the gawdamn thing in the first place. How you sound?" Jackie turns from his roommate's offer and points the blunt at me, and he giggles. "Told you bout parking there, Tommie. Told you they got a gimp living next door. Get your shit towed fast, boy. Them folk don't care nothing bout no bullshit, raggedy-ass Ford. Got a deal with the city on that spot."

"You're Richie's meter maid now?"

"Hell yeah. Just don't be parking your bullshit in fronta my crib, is all." Jackie laughs louder in his stinking clouds. "Hurts property value."

"I'm gone."

"All right then, Tommie. You ain't gotta go nowhere. Don't be so sensitive." He points at the back of Remi's head. "Chief, we got some skeezes from Seventy-ninth bout to come through, trying to get loose with the fellahs."

"Not from the motel?" Remi asks without looking at Westside. He clicks the mouse to protect this conqueror's new life.

"Naw, Rem-Dog. Ran cross these two at the bus stop off Cottage. Rolled up on um in your Rover. Fresh babes got to slobbering at the lip talking bout where 'y'all going to, who car's this, can we ride with y'all,' testifying on how down they wanna be. Course, I told them it was my boy's ride, and we couldn't get down with them unless they brung the get-down to him, right. They went to get another friend, then they'll be through the spot. Hehe- that's how smooth I am, Tommie. You wish you was playa-smooth like this here, don't you?"

"Yeah, I wish." I peek from Mahalia's shadows and the conqueror soon to be burned to ashes by this digital dragon. "Like you. Sure do."

"You told them it was my truck?" Remi's says.

"Of course I did, Rem-Dog. You my dog. Like how Snoop say it-"

"Right." Remi drops his square on the hardwood, squashes it with his shoe sole until ash simmers.

"Fresh babes," Jackie repeats as he steps out of that living room light. "Like eighteen, nineteen years old, no older than that. Just right. Even got a plump one coming for you, Tommie, if you wanna stay. Just like you like um. Had you in mind, Cuz, just in case. Better claim this one before James gets his greedies on her."

"Thick, that's what I like." My eyes swell from the blunt's burn. "Not plump- I like thick women."

"Well go home to your wife then, ungrateful, fatty freak muthafucka. Beggars can't be- punk bitch. We don't love these hos." Jackie sits under Lena, and his clouds turn her even creamier.

Descriere

When Tommie Simms loses his corporate job, he gets caught up in Chicago's treacherous underworld--the last fate anyone ever intended for him. Ojikutu is the author of "47th Street Black."