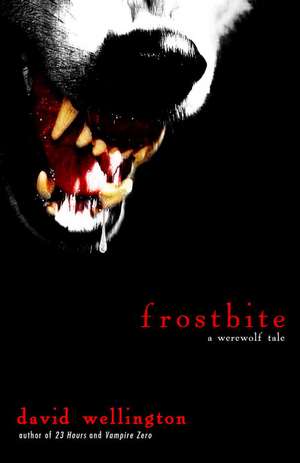

Frostbite: A Werewolf Tale

Autor David Wellingtonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 sep 2009

There's one sound a woman doesn't want to hear when she's lost and alone in the Arctic wilderness: a howl.

When a strange wolf's teeth slash Cheyenne's ankle to the bone, her old life ends, and she becomes the very monster that has haunted her nightmares for years. Worse, the only one who can understand what Chey has become is the manߝor wolfߝwho's doomed her to this fate. He also wants to chop her head off with an axe.

Yet as the line between human and beast blurs, so too does the distinction between hunter and hunted . . . for Chey is more than just the victim she appears to be. But once she's within killing range, she may find thatߝeven for a werewolfߝit's not always easy to go for the jugular.

Preț: 102.40 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 154

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.60€ • 21.30$ • 16.48£

19.60€ • 21.30$ • 16.48£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 21 aprilie-05 mai

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307460837

ISBN-10: 0307460835

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307460835

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 134 x 203 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: BROADWAY BOOKS

Notă biografică

DAVID WELLINGTON is the author of 23 Hours, Vampire Zero, 99 Coffins, 13 Bullets, and the Monster Island trilogy.

Extras

1.

The ground shook, and pine needles fell from the surrounding trees like green rain. Chey grabbed a projecting tree root to steady herself and looked up to see a wall of water come roaring down the defile, straight toward her.

She barely had time to see it before it hit—like the shivering surface of a swimming pool stood up on end. It was white and it roared and when it smacked into her it slapped her face and hands as hard as if she’d fallen onto a concrete sidewalk. Ice cold water surged up her nose and her mouth flew open, and then water was in her mouth and choking her, water thick with leaves and pine cones that bashed off her exposed skin like bullets, water full of rocks and tiny pebbles and reeking of fresh silt. Her hand was torn away from the root and her feet went out from under her and she was flying, tumbling, unable to control her limbs. Her back twisted around painfully as the water picked her up and slammed her down again, picked her up and dropped her hard. She felt her foot bounce painfully off a rock she couldn’t see—she couldn’t see anything, couldn’t hear anything but the voice of the water. She fought, desperately, to at least keep her head above the surface even as eddies and currents underneath sucked at her and tried to pull her down. She had a sense of incredible speed, as if she were being shot down the defile like a pinball hit by a plunger. She had a sickening, nauseating moment to realize that if her head hit a rock now she would just die—she was alone, and no one would be coming to help her—

And then she stopped, with a jerk that made her bones pop and shift inside her skin. The water poured over and around her and she heard a gurgling rasp and she was underwater, unable to breathe. Something was holding her down and she was drowning. With all the strength she had left she pushed upward, arcing her back, fighting the thing that held her. Fighting just to get her head above the water. She crested the surface with a sucking gasp and water flooded into her throat. Her body flailed and she was down again, submerged again. Somehow she fought her way back up.

White water surged and foamed around Chey’s face. She could barely keep her mouth above the freezing torrent. Her hands reached around behind her, desperately trying to find what was holding her down, even as the water rose and she heard bubbles popping in her ears. Her skin burned with the cold and she knew she would be dead in seconds, that she had failed.

She had not been prepared for this. She thought flash floods were something that happened in the desert, not in the Northwest Territories of the Canadian Arctic. Summer had come to the north, however, and with the strengthening sun trillions of tons of snow had begun to melt. All that runoff had to go somewhere. Chey had been hiking up the narrow defile, trying to get up to a ridge so she could see where she was. She had climbed down into the narrow canyon to get away from a knife-sharp wind. It was rough going, climbing as much with her hands as her feet, but she’d been making good progress. Then she’d paused because she’d thought she’d heard something. It was a low whirring sound like a herd of caribou galloping through the trees. She had thought maybe it was an earthquake.

Now, stuck on something, unable to get free, she tried to look around. The current had dragged her backward across ground she’d just covered, pulling her over sharp rocks that tore her parka, smearing her face with grit. She could see nothing but silver, silver bubbles, the silver surface of the water above her.

Her hands were numb and her fingers kept curling up from the cold as she searched behind herself. Chey begged and pleaded with them to work, to move again. She felt nylon, felt a nylon strap—there—her pack was snagged on a jagged spur of rock. Fumbling, cursing herself, she slipped the nylon strap free. Instantly the current grabbed her again, pulling her again downward, down into the defile. She grabbed at the first shadow she could find, which turned out to be a willow shrub. Hugging it tight to herself, she coughed and sputtered and pulled air back into her lungs.

Eventually she had enough strength to pull herself upward, out of the water. It now ran only waist deep. With effort she could wade through it. After the first explosive rush much of the water’s force had been spent and she could ford the brand new stream without being sucked under once more. On the far bank she dragged herself up onto cold mud and exposed tree roots and lay there, shivering, for a long time. She had to get dry, she knew. She had to warm herself up. She had fresh clothes and a lighter in her pack. Tinder and firewood would be easy enough to come by.

Slowly, painfully, she rolled over. She was still soaking wet and freezing. Her skin felt like clammy rubber. Once she warmed up she knew she would be in pain. She would have countless bruises to contend with and maybe even broken bones. It would be better than freezing to death, however. She pulled off her pack and reached for its flap. Unfamiliar scraps of fabric met her fingers.

The flap was torn in half. The pack itself was little more than a pile of rags. It must have been torn apart by the rocks when she’d been dragged by the current. It had protected her back from the same fate, but in the process it had come open and all of her supplies had come out. She shot her head around to look at the stream. Her gear, her dry clothes, her flashlight—her food—must be spread out over half the Territories, carried hither and yon by the water.

With shaking fingers she dug through the remains of the pack. There had to be something. Maybe the heavier objects had stayed put. She did find a couple of things. The base of her Coleman stove had been too heavy to wash away, though the fuel and the pots were lost, making it useless. Her cell phone was still sealed in its own compartment. It dribbled water as she held it up but it still chirped happily when she clicked it on.

She could call for help, she thought. Maybe things had gotten that bad.

No. She switched off the phone to conserve its battery. Not yet.

If she called for help now, it might come. She might get airlifted out to safety, to civilization. But then she would never be allowed to come back here, to try again. She would not be able to get what she’d come for. She shoved the phone in her pocket. She would need it, later, if she survived long enough.

The map she’d been given by the helicopter pilot was still there, though the water had made the ink run and she could barely read it. The rest of her stuff was gone. Her tent was lost. Her dry clothes were lost. Her weapon was nowhere to be found.

She spent the last of the daylight searching up and down the steep bank of the new stream. Maybe, just maybe something had washed up on the shore. Just as the moon came up she spied a glint of silver bobbing against a half-submerged log and jumped back into the water to get it. Praying that it was what she thought it was, she grabbed it up with both hands and brought it up to her face. It was the foil pack full of energy bars. Trail food. She started to cry, but she was so hungry she tore one open and ate it instead.

That night she buried herself under a heap of pine needles and old decaying leaves.

2.

In the morning she was itchy and damp and her skin felt like it had been scoured with a wire brush, but she knew that the second she tried to move out of her pile of needles, the real torment would begin.

She was right. When Chey did finally move her arms and legs and sit up, every muscle in her body felt like it had hardened into stone overnight and now was cracking. The stiffness hurt, really hurt, and she realized how rare it was to feel true pain when you lived in a civilized place. You might stub your toe on your coffee table, or even jam your finger in a car door. But you never felt a river pick you up and bang you against a bunch of jagged rocks until it got bored with you.

She sat curled around her knees for a while, just breathing.

Eventually she managed to get up on her feet. She had to make a decision. North, or south. South meant giving up. Turning her back on what she’d come for.

She checked her compass and headed north.

After an hour of walking the stiffness started to go away. It was replaced by searing pain that came with every step she took in her water-logged boots, but that she could wince away.

She kept walking, through the trees, until she thought she might collapse from exhaustion. The sun was still high above the green and yellow branches, but she couldn’t take another step. So she sat down. She thought about crying for a while, but decided she didn’t have the energy left. So instead she unwrapped one of her protein bars and ate it. When she was done she got back up and started walking again, because there was nothing else to do. Nothing that would help her.

Time didn’t mean much among the trees, because everything looked the same and every step she took seemed exactly like the one before it. But eventually it got dark.

She kept walking.

Until she thought she heard something. A footfall on a crust of snow, maybe. Or just the sound of something breathing. Something that wasn’t human.

Keep walking, she told herself. It’s more afraid of you than—

She couldn’t bring herself to finish that thought without laughing out loud. Which she really didn’t want to do.

She came to a gap in the cover of branches overhead and a little moonlight leaked through, enough that she could look around her. The sky was alive with colors: the aurora borealis burning and raging overhead. She forced herself not to watch it, though—she needed to scan the shadows around her, searching for any sign of pursuit.

She peered and squinted so hard into the gloom that she almost fell, her hands wheeling out in front of her to catch herself, and then she decided she needed to keep an eye on her footing. Buckled by permafrost, the ground refused to lie flat. Instead it bunched up in wrinkles that could snag her ankle if she wasn’t careful. The black trees stood up in random directions, at angles to the earth. The ground rose in sharp hillocks and sudden crevasses that hid glinting ice. Chey’s feet kept catching on exposed roots and broken rocks. She could barely trust her perceptions anyway, not after what she’d been through, with nothing to eat but energy bars, no real sleep, no shelter except the fleece lining of her torn parka.

There was nothing out there, she told herself. It had just been her half-starved brain playing tricks on her. The forest was empty of life. She hadn’t seen so much as a bird or a chipmunk all day. She stopped in her tracks and turned around to look behind her, just to prove to herself she wasn’t being followed.

Between two of the trees a pair of yellow eyes flickered into glowing life, blazing like the reflectors of a pair of flashlights. They caught the fish-belly white moonlight and speared her with it. Froze her in place. Slowly, languorously, the eyes closed again and were gone, like embers flickering out at the bottom of a dead campfire.

“Oh, shit,” she breathed, and then slammed a hand over her mouth. Underneath the parka she could feel the hair on the back of her arms standing up. Slowly she turned around in a circle. Wolf. That had been a wolf, a timber wolf. She was certain. Were there more of them? Was there a pack nearby?

She heard them howl then. She’d heard dogs howl at the moon before, but not like this. The howling went on and on and on, with new voices jumping in and following, a sound almost mournful in tone. They were talking among themselves and she figured they were telling each other where to find her.

She lacked the energy to go another step. Her face contracted in a grimace of real terror. Then she dug deeper inside of herself, deeper than she’d ever been before, and she ran.

The trees flashed by her, leaning to the left, the right. The gnarled ground tore at her feet, made her ankles ache and burn. She kept her arms up in front of her—despite the half-full moon she could barely see anything, and could easily collide face first with a tree trunk and snap her neck. She knew it was foolish, knew that running was the worst thing she could do. But it was the only thing she could do.

To her left she saw flickering gold. The eyes again. Was it the same animal? She couldn’t tell. The eyes floated alongside her, easily keeping up with her pace. The eyes weren’t expending any effort at all. The feet that belonged to those eyes knew this rough land by instinct, could find the perfect footing without even looking. The Northwest Territories belonged to those eyes, those feet. Not to human weakness.

To her right she heard panting. More than one of them over there, too. It was a pack, a whole pack, and they were testing her. Seeing how fast she could run, how strong she was.

She was going to die here, as far from civilization as anyone could ever be. She was going to die.

No. Not quite yet.

Evolution had given her certain advantages. It had given her hands. Her distant ancestors had used those hands to climb, to escape from predators. She needed to unlearn two million years of civilization in a hurry. Ahead of her a tree stood up from the leaning forest, a big half-dead paper birch with thick limbs starting two meters off the ground. It rose five meters taller than anything around it. She steeled herself, clenched and unclenched her hands a few times, then dashed right at it, her aching feet catching on the loose bark that pulled away like sloughing skin. Her hands reached up and grabbed at thin branches that couldn’t possibly hold her weight, twigs really. She shoved herself up the tree, her body, her face pressed as tightly to the trunk as she could get them, until a wave of ripped bark and crystalline snow came boiling across her face. Suddenly she was holding on to a thick branch three meters above the earth. She pulled herself up onto it, grabbed it with her whole body. Looked down

The ground shook, and pine needles fell from the surrounding trees like green rain. Chey grabbed a projecting tree root to steady herself and looked up to see a wall of water come roaring down the defile, straight toward her.

She barely had time to see it before it hit—like the shivering surface of a swimming pool stood up on end. It was white and it roared and when it smacked into her it slapped her face and hands as hard as if she’d fallen onto a concrete sidewalk. Ice cold water surged up her nose and her mouth flew open, and then water was in her mouth and choking her, water thick with leaves and pine cones that bashed off her exposed skin like bullets, water full of rocks and tiny pebbles and reeking of fresh silt. Her hand was torn away from the root and her feet went out from under her and she was flying, tumbling, unable to control her limbs. Her back twisted around painfully as the water picked her up and slammed her down again, picked her up and dropped her hard. She felt her foot bounce painfully off a rock she couldn’t see—she couldn’t see anything, couldn’t hear anything but the voice of the water. She fought, desperately, to at least keep her head above the surface even as eddies and currents underneath sucked at her and tried to pull her down. She had a sense of incredible speed, as if she were being shot down the defile like a pinball hit by a plunger. She had a sickening, nauseating moment to realize that if her head hit a rock now she would just die—she was alone, and no one would be coming to help her—

And then she stopped, with a jerk that made her bones pop and shift inside her skin. The water poured over and around her and she heard a gurgling rasp and she was underwater, unable to breathe. Something was holding her down and she was drowning. With all the strength she had left she pushed upward, arcing her back, fighting the thing that held her. Fighting just to get her head above the water. She crested the surface with a sucking gasp and water flooded into her throat. Her body flailed and she was down again, submerged again. Somehow she fought her way back up.

White water surged and foamed around Chey’s face. She could barely keep her mouth above the freezing torrent. Her hands reached around behind her, desperately trying to find what was holding her down, even as the water rose and she heard bubbles popping in her ears. Her skin burned with the cold and she knew she would be dead in seconds, that she had failed.

She had not been prepared for this. She thought flash floods were something that happened in the desert, not in the Northwest Territories of the Canadian Arctic. Summer had come to the north, however, and with the strengthening sun trillions of tons of snow had begun to melt. All that runoff had to go somewhere. Chey had been hiking up the narrow defile, trying to get up to a ridge so she could see where she was. She had climbed down into the narrow canyon to get away from a knife-sharp wind. It was rough going, climbing as much with her hands as her feet, but she’d been making good progress. Then she’d paused because she’d thought she’d heard something. It was a low whirring sound like a herd of caribou galloping through the trees. She had thought maybe it was an earthquake.

Now, stuck on something, unable to get free, she tried to look around. The current had dragged her backward across ground she’d just covered, pulling her over sharp rocks that tore her parka, smearing her face with grit. She could see nothing but silver, silver bubbles, the silver surface of the water above her.

Her hands were numb and her fingers kept curling up from the cold as she searched behind herself. Chey begged and pleaded with them to work, to move again. She felt nylon, felt a nylon strap—there—her pack was snagged on a jagged spur of rock. Fumbling, cursing herself, she slipped the nylon strap free. Instantly the current grabbed her again, pulling her again downward, down into the defile. She grabbed at the first shadow she could find, which turned out to be a willow shrub. Hugging it tight to herself, she coughed and sputtered and pulled air back into her lungs.

Eventually she had enough strength to pull herself upward, out of the water. It now ran only waist deep. With effort she could wade through it. After the first explosive rush much of the water’s force had been spent and she could ford the brand new stream without being sucked under once more. On the far bank she dragged herself up onto cold mud and exposed tree roots and lay there, shivering, for a long time. She had to get dry, she knew. She had to warm herself up. She had fresh clothes and a lighter in her pack. Tinder and firewood would be easy enough to come by.

Slowly, painfully, she rolled over. She was still soaking wet and freezing. Her skin felt like clammy rubber. Once she warmed up she knew she would be in pain. She would have countless bruises to contend with and maybe even broken bones. It would be better than freezing to death, however. She pulled off her pack and reached for its flap. Unfamiliar scraps of fabric met her fingers.

The flap was torn in half. The pack itself was little more than a pile of rags. It must have been torn apart by the rocks when she’d been dragged by the current. It had protected her back from the same fate, but in the process it had come open and all of her supplies had come out. She shot her head around to look at the stream. Her gear, her dry clothes, her flashlight—her food—must be spread out over half the Territories, carried hither and yon by the water.

With shaking fingers she dug through the remains of the pack. There had to be something. Maybe the heavier objects had stayed put. She did find a couple of things. The base of her Coleman stove had been too heavy to wash away, though the fuel and the pots were lost, making it useless. Her cell phone was still sealed in its own compartment. It dribbled water as she held it up but it still chirped happily when she clicked it on.

She could call for help, she thought. Maybe things had gotten that bad.

No. She switched off the phone to conserve its battery. Not yet.

If she called for help now, it might come. She might get airlifted out to safety, to civilization. But then she would never be allowed to come back here, to try again. She would not be able to get what she’d come for. She shoved the phone in her pocket. She would need it, later, if she survived long enough.

The map she’d been given by the helicopter pilot was still there, though the water had made the ink run and she could barely read it. The rest of her stuff was gone. Her tent was lost. Her dry clothes were lost. Her weapon was nowhere to be found.

She spent the last of the daylight searching up and down the steep bank of the new stream. Maybe, just maybe something had washed up on the shore. Just as the moon came up she spied a glint of silver bobbing against a half-submerged log and jumped back into the water to get it. Praying that it was what she thought it was, she grabbed it up with both hands and brought it up to her face. It was the foil pack full of energy bars. Trail food. She started to cry, but she was so hungry she tore one open and ate it instead.

That night she buried herself under a heap of pine needles and old decaying leaves.

2.

In the morning she was itchy and damp and her skin felt like it had been scoured with a wire brush, but she knew that the second she tried to move out of her pile of needles, the real torment would begin.

She was right. When Chey did finally move her arms and legs and sit up, every muscle in her body felt like it had hardened into stone overnight and now was cracking. The stiffness hurt, really hurt, and she realized how rare it was to feel true pain when you lived in a civilized place. You might stub your toe on your coffee table, or even jam your finger in a car door. But you never felt a river pick you up and bang you against a bunch of jagged rocks until it got bored with you.

She sat curled around her knees for a while, just breathing.

Eventually she managed to get up on her feet. She had to make a decision. North, or south. South meant giving up. Turning her back on what she’d come for.

She checked her compass and headed north.

After an hour of walking the stiffness started to go away. It was replaced by searing pain that came with every step she took in her water-logged boots, but that she could wince away.

She kept walking, through the trees, until she thought she might collapse from exhaustion. The sun was still high above the green and yellow branches, but she couldn’t take another step. So she sat down. She thought about crying for a while, but decided she didn’t have the energy left. So instead she unwrapped one of her protein bars and ate it. When she was done she got back up and started walking again, because there was nothing else to do. Nothing that would help her.

Time didn’t mean much among the trees, because everything looked the same and every step she took seemed exactly like the one before it. But eventually it got dark.

She kept walking.

Until she thought she heard something. A footfall on a crust of snow, maybe. Or just the sound of something breathing. Something that wasn’t human.

Keep walking, she told herself. It’s more afraid of you than—

She couldn’t bring herself to finish that thought without laughing out loud. Which she really didn’t want to do.

She came to a gap in the cover of branches overhead and a little moonlight leaked through, enough that she could look around her. The sky was alive with colors: the aurora borealis burning and raging overhead. She forced herself not to watch it, though—she needed to scan the shadows around her, searching for any sign of pursuit.

She peered and squinted so hard into the gloom that she almost fell, her hands wheeling out in front of her to catch herself, and then she decided she needed to keep an eye on her footing. Buckled by permafrost, the ground refused to lie flat. Instead it bunched up in wrinkles that could snag her ankle if she wasn’t careful. The black trees stood up in random directions, at angles to the earth. The ground rose in sharp hillocks and sudden crevasses that hid glinting ice. Chey’s feet kept catching on exposed roots and broken rocks. She could barely trust her perceptions anyway, not after what she’d been through, with nothing to eat but energy bars, no real sleep, no shelter except the fleece lining of her torn parka.

There was nothing out there, she told herself. It had just been her half-starved brain playing tricks on her. The forest was empty of life. She hadn’t seen so much as a bird or a chipmunk all day. She stopped in her tracks and turned around to look behind her, just to prove to herself she wasn’t being followed.

Between two of the trees a pair of yellow eyes flickered into glowing life, blazing like the reflectors of a pair of flashlights. They caught the fish-belly white moonlight and speared her with it. Froze her in place. Slowly, languorously, the eyes closed again and were gone, like embers flickering out at the bottom of a dead campfire.

“Oh, shit,” she breathed, and then slammed a hand over her mouth. Underneath the parka she could feel the hair on the back of her arms standing up. Slowly she turned around in a circle. Wolf. That had been a wolf, a timber wolf. She was certain. Were there more of them? Was there a pack nearby?

She heard them howl then. She’d heard dogs howl at the moon before, but not like this. The howling went on and on and on, with new voices jumping in and following, a sound almost mournful in tone. They were talking among themselves and she figured they were telling each other where to find her.

She lacked the energy to go another step. Her face contracted in a grimace of real terror. Then she dug deeper inside of herself, deeper than she’d ever been before, and she ran.

The trees flashed by her, leaning to the left, the right. The gnarled ground tore at her feet, made her ankles ache and burn. She kept her arms up in front of her—despite the half-full moon she could barely see anything, and could easily collide face first with a tree trunk and snap her neck. She knew it was foolish, knew that running was the worst thing she could do. But it was the only thing she could do.

To her left she saw flickering gold. The eyes again. Was it the same animal? She couldn’t tell. The eyes floated alongside her, easily keeping up with her pace. The eyes weren’t expending any effort at all. The feet that belonged to those eyes knew this rough land by instinct, could find the perfect footing without even looking. The Northwest Territories belonged to those eyes, those feet. Not to human weakness.

To her right she heard panting. More than one of them over there, too. It was a pack, a whole pack, and they were testing her. Seeing how fast she could run, how strong she was.

She was going to die here, as far from civilization as anyone could ever be. She was going to die.

No. Not quite yet.

Evolution had given her certain advantages. It had given her hands. Her distant ancestors had used those hands to climb, to escape from predators. She needed to unlearn two million years of civilization in a hurry. Ahead of her a tree stood up from the leaning forest, a big half-dead paper birch with thick limbs starting two meters off the ground. It rose five meters taller than anything around it. She steeled herself, clenched and unclenched her hands a few times, then dashed right at it, her aching feet catching on the loose bark that pulled away like sloughing skin. Her hands reached up and grabbed at thin branches that couldn’t possibly hold her weight, twigs really. She shoved herself up the tree, her body, her face pressed as tightly to the trunk as she could get them, until a wave of ripped bark and crystalline snow came boiling across her face. Suddenly she was holding on to a thick branch three meters above the earth. She pulled herself up onto it, grabbed it with her whole body. Looked down

Recenzii

"Entertaining and thrilling...Wellington is a vivid storyteller, whether describing gruesome attacks, expressing the subtle attraction between man and woman or chronicling the life of a troubled teen"

-Associated Press

-Associated Press

Descriere

Horror-star Wellington returns with the first book in a new series, introducing an unforgettable heroine with an impossible choice to make. "Frostbite" also presents a brilliant twist on the werewolf genre, in which the hunter becomes the hunted.