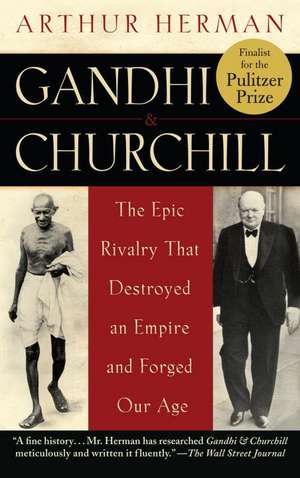

Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry That Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age

Autor Arthur Hermanen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 mar 2009

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Audies (2009)

In this fascinating and meticulously researched book, bestselling historian Arthur Herman sheds new light on two of the most universally recognizable icons of the twentieth century, and reveals how their forty-year rivalry sealed the fate of India and the British Empire.

They were born worlds apart: Winston Churchill to Britain’s most glamorous aristocratic family, Mohandas Gandhi to a pious middle-class household in a provincial town in India. Yet Arthur Herman reveals how their lives and careers became intertwined as the twentieth century unfolded. Both men would go on to lead their nations through harrowing trials and two world wars—and become locked in a fierce contest of wills that would decide the fates of countries, continents, and ultimately an empire. Here is a sweeping epic with a fascinating supporting cast, and a brilliant narrative parable of two men whose great successes were always haunted by personal failure—and whose final moments of triumph were overshadowed by the loss of what they held most dear.

Preț: 131.96 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 198

Preț estimativ în valută:

25.26€ • 26.27$ • 21.13£

25.26€ • 26.27$ • 21.13£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553383768

ISBN-10: 0553383760

Pagini: 718

Ilustrații: 3 INTERIOR MAPS 3 B&W PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 136 x 209 x 41 mm

Greutate: 0.82 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0553383760

Pagini: 718

Ilustrații: 3 INTERIOR MAPS 3 B&W PHOTO INSERTS

Dimensiuni: 136 x 209 x 41 mm

Greutate: 0.82 kg

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Arthur Herman is the bestselling author of How the Scots Invented the Modern World, which has sold over 350,000 copies worldwide, and To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World, which was nominated for the prestigious Mountbatten Prize in 2005. He is a former professor of history at Georgetown University, Catholic University, and the Smithsonian’s Campus on the Mall. He and his wife live in central Virginia.

Extras

Chapter One

The Churchills and the Raj

And Blenheim’s Tower shall triumph O’er Whitehall—anonymous pamphleteer, 1705

On November 30, 1874, another baby boy was born on the other side of the world. This one also first saw light in his grandfather’s house, but on a far grander scale—indeed, in the biggest private home in Britain.

Surrounded by three thousand acres of “green lawns and shining water, banks of laurel and fern, groves of oak and cedar, fountains and islands,” Blenheim Castle boasted 187 rooms.1 It was in a drafty bedroom on the first floor that Jennie Jerome Churchill gave birth to her first child. “Dark eyes and hair” was how her twenty-five-year-old husband, Randolph Churchill, described the boy to Jennie’s mother, and “wonderfully very pretty everybody says.”2

The child’s baptized name would be Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill. If the Gandhis were unknown outside their tiny Indian state, the Churchill name was steeped in history. John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, had been Europe’s most acclaimed general and the most powerful man in Britain. His series of victories over France in the first decade of the eighteenth century had made Britain a world-class power. A grateful Queen Anne gave him the royal estate at Woodstock on which to build a palace, which he named after his most famous victory. For Winston Churchill, Blenheim Castle would always symbolize a heritage of glory and a family born to greatness.

Yet the first Duke of Marlborough had been followed by a succession of nonentities. If the power and wealth of England expanded to unimagined heights over the next century, that of the Churchills steadily declined.

The vast fortune that the first duke accumulated in the age of Queen Anne was squandered by his successors. When Randolph’s father inherited the title in 1857, the same year the Great Mutiny raged in India, he had been faced, like his father and grandfather before him, by debts of Himalayan proportions and slender means with which to meet them. Randolph’s grandfather had already turned Blenheim into a public museum, charging visitors one shilling admission. Randolph’s father would have to sell off priceless paintings (including a Raphael and Van Dyck’s splendid equestrian portrait of King Charles I, still the largest painting in the National Gallery), the fabulous Marlborough collection of gems, and the eighteen-thousand-volume Sunderland library, in order to make ends meet.3

In the financial squeeze which was beginning to affect nearly all the Victorian aristocracy, the Spencer-Churchills felt the pinch more than most. For Randolph Churchill, the Marlborough legacy was a bankrupt inheritance. In a crucial sense, it was no inheritance at all. His older brother, Lord Blandford, would take over the title, Blenheim, and the remaining estates. What was left for him, and for his heirs, was relatively paltry (although much more than the patrimony of the great majority of Britons), with £4,200 a year and the lease on a house in Mayfair.4

So the new father, twenty-five-year-old Randolph, was going to have to cut his own way into the world, just as his son would. And both would choose the same way: politics.

Randolph was the family rebel, a natural contrarian and malcontent. Beneath his pale bulging eyes, large exquisite mustache, and cool aristocratic hauteur was the soul of a headstrong alpha male. As he told his friend Lord Rosebery, “I like to be the boss.”5 Young Lord Randolph was determined to make a name for himself as a member of Parliament. All he needed was an issue.

In 1874 an issue was not easy to find. At the time when Winston Churchill was born, British politics reflected a consensus that the country had not known in nearly a hundred years—and soon would never know again.6 The last big domestic battle had been fought over the Second Reform Bill of 1867, when crowds in London clashed in the streets with police and tore up railings around Hyde Park. Passage of the act opened the door to Britain’s first working-class voters. But almost a decade later neither Conservatives nor Liberals were inclined to let it swing open any wider.

Both parties agreed that free trade was the cornerstone of the British economy, still the most productive in the world. Both agreed on the importance of keeping the gold standard. They even agreed that social reform was best left in private and local hands, although Parliament would occasionally give its approval to a round of slum clearances or a comprehensive health act. A twelve-hour day for the average workman, and ten and a half hours for women and young persons older than thirteen, made eminent good sense economically and morally. Giving them a government retirement pension or an unemployment check did not.7

Tories and Liberals also agreed on maintaining an empire that was without rival and on defending it with a navy that was second to none. In 1874 that empire was not only the most extensive but the most cohesive on the planet.8 It emcompassed Britain itself, with England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland welded together under a single government and crown. Across the Atlantic there were the islands of the West Indies and also Canada, the empire’s first self-governing “dominion”—a word that would loom large in the later battles between Churchill and Gandhi.

Then there were the prosperous and stable colonies of white settlers in New Zealand and Australia which, although more than ten thousand miles away, felt a strong bond of loyalty to Britain and the Crown. Britain also directed the fate of two colonies in southern Africa, the Cape Colony and Natal, in addition to Lagos in Nigeria. Hong Kong, Singapore, and some scattered possessions in Asia and the Mediterranean completed the collection.

But the centerpiece of the empire was India, where Britain was the undisputed master of more than a quarter billion people. In 1874 two out of every three British subjects was an Indian. Since the Mutiny both political parties had closed ranks about dealing with India. The power of the British system of governance, or the Raj as it was called after the Mutiny, had become more extensive and more streamlined. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had also made it much easier to reach the ancient subcontinent than in the days before the Mutiny.

Most Britons still knew almost nothing about the subcontinent or its peoples. Nonetheless, the fact that they possessed India, and governed it virtually as a separate empire, gave Britons a halo of superpower status that no other people or nation could match. The attitude was summed up nine years later in Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Ave Imperatrix”:

And all are bred to do your will

By land and sea—wherever flies

The Flag, to fight and follow still,

And work your Empire’s destinies.

In the midst of this triumphant march to the future, the only hint of trouble was Ireland. The question of whether the Catholic Irish would ever enjoy any degree of “home rule” had become a live issue in Irish politics. In 1875 it sent Charles Stewart Parnell to Parliament, but otherwise Irish nationalism hardly registered in Westminster; nor did any other issue.*

There seemed to be no burning questions to divide public opinion, no bitter clash of interests, no looming threats on the horizon for an unknown but ambitious politician to seize on. By 1880 Randolph realized he had only one way to get attention in Parliament: by becoming a nuisance and stirring things up.

The issue Winston’s father seized upon was the Bradlaugh case. Charles Bradlaugh was a Liberal and a radical atheist who, when elected to Parliament that year, refused to take the oath of allegiance needed to take his seat in the Commons, because it contained the words “so help me God.” The question of whether Bradlaugh should be allowed to take his seat anyway stirred the hearts of many Conservative members, and Randolph’s friend Sir Henry Drummond Wolff asked his help against Bradlaugh.

Randolph soon discovered that Bradlaugh made an easy target.9 He was not only a free thinker but a socialist, an advocate of birth control, and even a critic of Empire. Bradlaugh was also a radical republican who denounced the monarchy and aristocrats like Randolph in heated terms.† So when Randolph made his speech on May 24, 1880, condemning Bradlaugh for his atheism, he also read aloud from one of Bradlaugh’s pamphlets calling the royal family “small German breast-beating wanderers, whose only merit is their loving hatred of one another.” He then hurled the pamphlet on the floor and stamped on it.

The House was ecstatic. “Everyone was full of it,” Jennie wrote, who

* It would be registering sooner than most realized. Ironically, Kipling’s triumphant poem was composed in 1882, after the exposure of an Irish plot to assassinate Queen Victoria, to reassure the British public. Winston Churchill’s earliest childhood memory was of wandering through Dublin’s Phoenix Park and seeing the point where the British viceroy had been murdered only a couple of years earlier.

† He would also be one of the first champions of Indian nationalism. When he died in 1891 and was buried in London’s Brookwood Cemetery, among the three thousand mourners who attended the funeral would be a young Mohandas Gandhi.

had watched the speech from the gallery, “and rushed up and congratulated me to such an extent that I felt as though I had made it.”10 Lord Randolph Churchill’s career was launched as a sensational, even outrageous, headline-grabber. Together with Wolff and another friend, Sir Henry Gorst, he formed what came to be known as the Fourth Party,* a junta of Tory mavericks who ripped into their own party leaders any time they sided with the government, to the delight of journalists and newspaper readers.

Suddenly, thanks to Randolph Churchill, politics was fun again. When Bradlaugh was reelected in spite of being denied his seat, Randolph attacked him again, carefully playing it for laughs and for the gallery and the news media; when the voters of Northampton insisted on returning Bradlaugh again, Randolph did the same thing. And then a fourth and a fifth time: at one point Bradlaugh had to be escorted out of the House chamber by police and locked up in the Big Ben tower. Some people began to joke that Randolph must be bribing Northampton voters to keep voting for Bradlaugh, since they were also keeping Randolph in the headlines.11

Lord Randolph had the good sense to realize that while the Bradlaugh case had launched his political rise, he needed more substantial issues to sustain it. He tried Ireland for a while, taking up the cause of Ulster Protestants in the North and lambasting the Irish nationalists of the south. He tested a new catchphrase, “Tory Democracy,” urging Conservatives to win votes and allies among Britain’s newly enfranchised working class—but the phrase had more headline appeal than substance or thought behind it. He even tried Egypt, furiously denouncing the Liberal government’s support of its corrupt ruler. Finally in the summer of 1884, the man an American journalist called “the political sensation of England” turned to India.

Crucial though India was to the empire, few politicians had any expertise in the empire’s greatest possession. In November 1884 Churchill planned a major tour of India. His friend Wilfred Blunt, who had already traveled widely there, set up the key introductions. He predicted “a great future for any statesman who will preach Tory Democracy in India.”12 Lord Randolph left in December and did not return to London until April 1885, after logging more than 22,800 miles. He then delivered a round of fiery speeches denouncing the Gladstone government’s

* After the Liberals, Tories, and Irish Nationalists.

policies there, from neglecting the threat from Russia to failing to gain more native participation in the Raj. The speeches established him as the Conservatives’ “front line spokesman on India.”13 So when they returned to power in June that year, he was the obvious candidate for secretary of state for India.

In terms of direct influence over people’s lives, it was the single most powerful position in the cabinet, even more powerful than prime minister. At age thirty-six, Randolph Churchill would be overseeing an imperial domain that was, as he discovered in his travels and readings, unique in British history—perhaps unique in human history.

How the British built an empire in India, conquering one of the most ancient and powerful civilizations in the world, is an epic of heroism, sacrifice, ruthlessness, and greed. But it is also the story of a growing sense of mission, even destiny: the growing conviction that the British were meant to rule India not only for their own interests but for the sake of the Indians as well. That belief would decisively shape the character not only of the British Empire in India but also of Randolph’s son Winston Churchill—the man into whose hands the destiny of the Raj would ultimately fall.

Ironically, that empire’s founding fathers, the group of God-fearing merchants living in Shakespeare’s London who created the Honorable East India Company, never intended to go to India at all—any more than Queen Elizabeth I did when she gave them a royal charter on the last day of 1600. Their aim was to get to the Spice Islands (the Molucca Islands in today’s Indonesia), where Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch merchants and adventurers were battling over fortunes in nutmeg, cloves, and mace. The East India Company’s initial stop at Surat, on India’s west coast, was supposed to be only a layover for ventures farther east.

But when the Dutch tortured and murdered ten of their merchants in the island of Amboyne in 1623 and foisted the English out of the Spice Islands, the London-based company had nowhere else to go.14 By 1650, the year John Churchill was born in Devon, the East India Company found itself precariously perched in a tiny settlement near Surat called Fort St. George, doing business at the pleasure of the rulers of India, the Mughal emperors—at the time probably the richest human beings in the world. In 1674 the company acquired a similar outpost at Bombay, which King Charles II had received as a wedding present from the king of Portugal. Then in 1690 it built another, in Bengal at Kalikat, which the English pronounced Calcutta.

The Churchills and the Raj

And Blenheim’s Tower shall triumph O’er Whitehall—anonymous pamphleteer, 1705

On November 30, 1874, another baby boy was born on the other side of the world. This one also first saw light in his grandfather’s house, but on a far grander scale—indeed, in the biggest private home in Britain.

Surrounded by three thousand acres of “green lawns and shining water, banks of laurel and fern, groves of oak and cedar, fountains and islands,” Blenheim Castle boasted 187 rooms.1 It was in a drafty bedroom on the first floor that Jennie Jerome Churchill gave birth to her first child. “Dark eyes and hair” was how her twenty-five-year-old husband, Randolph Churchill, described the boy to Jennie’s mother, and “wonderfully very pretty everybody says.”2

The child’s baptized name would be Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill. If the Gandhis were unknown outside their tiny Indian state, the Churchill name was steeped in history. John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough, had been Europe’s most acclaimed general and the most powerful man in Britain. His series of victories over France in the first decade of the eighteenth century had made Britain a world-class power. A grateful Queen Anne gave him the royal estate at Woodstock on which to build a palace, which he named after his most famous victory. For Winston Churchill, Blenheim Castle would always symbolize a heritage of glory and a family born to greatness.

Yet the first Duke of Marlborough had been followed by a succession of nonentities. If the power and wealth of England expanded to unimagined heights over the next century, that of the Churchills steadily declined.

The vast fortune that the first duke accumulated in the age of Queen Anne was squandered by his successors. When Randolph’s father inherited the title in 1857, the same year the Great Mutiny raged in India, he had been faced, like his father and grandfather before him, by debts of Himalayan proportions and slender means with which to meet them. Randolph’s grandfather had already turned Blenheim into a public museum, charging visitors one shilling admission. Randolph’s father would have to sell off priceless paintings (including a Raphael and Van Dyck’s splendid equestrian portrait of King Charles I, still the largest painting in the National Gallery), the fabulous Marlborough collection of gems, and the eighteen-thousand-volume Sunderland library, in order to make ends meet.3

In the financial squeeze which was beginning to affect nearly all the Victorian aristocracy, the Spencer-Churchills felt the pinch more than most. For Randolph Churchill, the Marlborough legacy was a bankrupt inheritance. In a crucial sense, it was no inheritance at all. His older brother, Lord Blandford, would take over the title, Blenheim, and the remaining estates. What was left for him, and for his heirs, was relatively paltry (although much more than the patrimony of the great majority of Britons), with £4,200 a year and the lease on a house in Mayfair.4

So the new father, twenty-five-year-old Randolph, was going to have to cut his own way into the world, just as his son would. And both would choose the same way: politics.

Randolph was the family rebel, a natural contrarian and malcontent. Beneath his pale bulging eyes, large exquisite mustache, and cool aristocratic hauteur was the soul of a headstrong alpha male. As he told his friend Lord Rosebery, “I like to be the boss.”5 Young Lord Randolph was determined to make a name for himself as a member of Parliament. All he needed was an issue.

In 1874 an issue was not easy to find. At the time when Winston Churchill was born, British politics reflected a consensus that the country had not known in nearly a hundred years—and soon would never know again.6 The last big domestic battle had been fought over the Second Reform Bill of 1867, when crowds in London clashed in the streets with police and tore up railings around Hyde Park. Passage of the act opened the door to Britain’s first working-class voters. But almost a decade later neither Conservatives nor Liberals were inclined to let it swing open any wider.

Both parties agreed that free trade was the cornerstone of the British economy, still the most productive in the world. Both agreed on the importance of keeping the gold standard. They even agreed that social reform was best left in private and local hands, although Parliament would occasionally give its approval to a round of slum clearances or a comprehensive health act. A twelve-hour day for the average workman, and ten and a half hours for women and young persons older than thirteen, made eminent good sense economically and morally. Giving them a government retirement pension or an unemployment check did not.7

Tories and Liberals also agreed on maintaining an empire that was without rival and on defending it with a navy that was second to none. In 1874 that empire was not only the most extensive but the most cohesive on the planet.8 It emcompassed Britain itself, with England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland welded together under a single government and crown. Across the Atlantic there were the islands of the West Indies and also Canada, the empire’s first self-governing “dominion”—a word that would loom large in the later battles between Churchill and Gandhi.

Then there were the prosperous and stable colonies of white settlers in New Zealand and Australia which, although more than ten thousand miles away, felt a strong bond of loyalty to Britain and the Crown. Britain also directed the fate of two colonies in southern Africa, the Cape Colony and Natal, in addition to Lagos in Nigeria. Hong Kong, Singapore, and some scattered possessions in Asia and the Mediterranean completed the collection.

But the centerpiece of the empire was India, where Britain was the undisputed master of more than a quarter billion people. In 1874 two out of every three British subjects was an Indian. Since the Mutiny both political parties had closed ranks about dealing with India. The power of the British system of governance, or the Raj as it was called after the Mutiny, had become more extensive and more streamlined. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had also made it much easier to reach the ancient subcontinent than in the days before the Mutiny.

Most Britons still knew almost nothing about the subcontinent or its peoples. Nonetheless, the fact that they possessed India, and governed it virtually as a separate empire, gave Britons a halo of superpower status that no other people or nation could match. The attitude was summed up nine years later in Rudyard Kipling’s poem “Ave Imperatrix”:

And all are bred to do your will

By land and sea—wherever flies

The Flag, to fight and follow still,

And work your Empire’s destinies.

In the midst of this triumphant march to the future, the only hint of trouble was Ireland. The question of whether the Catholic Irish would ever enjoy any degree of “home rule” had become a live issue in Irish politics. In 1875 it sent Charles Stewart Parnell to Parliament, but otherwise Irish nationalism hardly registered in Westminster; nor did any other issue.*

There seemed to be no burning questions to divide public opinion, no bitter clash of interests, no looming threats on the horizon for an unknown but ambitious politician to seize on. By 1880 Randolph realized he had only one way to get attention in Parliament: by becoming a nuisance and stirring things up.

The issue Winston’s father seized upon was the Bradlaugh case. Charles Bradlaugh was a Liberal and a radical atheist who, when elected to Parliament that year, refused to take the oath of allegiance needed to take his seat in the Commons, because it contained the words “so help me God.” The question of whether Bradlaugh should be allowed to take his seat anyway stirred the hearts of many Conservative members, and Randolph’s friend Sir Henry Drummond Wolff asked his help against Bradlaugh.

Randolph soon discovered that Bradlaugh made an easy target.9 He was not only a free thinker but a socialist, an advocate of birth control, and even a critic of Empire. Bradlaugh was also a radical republican who denounced the monarchy and aristocrats like Randolph in heated terms.† So when Randolph made his speech on May 24, 1880, condemning Bradlaugh for his atheism, he also read aloud from one of Bradlaugh’s pamphlets calling the royal family “small German breast-beating wanderers, whose only merit is their loving hatred of one another.” He then hurled the pamphlet on the floor and stamped on it.

The House was ecstatic. “Everyone was full of it,” Jennie wrote, who

* It would be registering sooner than most realized. Ironically, Kipling’s triumphant poem was composed in 1882, after the exposure of an Irish plot to assassinate Queen Victoria, to reassure the British public. Winston Churchill’s earliest childhood memory was of wandering through Dublin’s Phoenix Park and seeing the point where the British viceroy had been murdered only a couple of years earlier.

† He would also be one of the first champions of Indian nationalism. When he died in 1891 and was buried in London’s Brookwood Cemetery, among the three thousand mourners who attended the funeral would be a young Mohandas Gandhi.

had watched the speech from the gallery, “and rushed up and congratulated me to such an extent that I felt as though I had made it.”10 Lord Randolph Churchill’s career was launched as a sensational, even outrageous, headline-grabber. Together with Wolff and another friend, Sir Henry Gorst, he formed what came to be known as the Fourth Party,* a junta of Tory mavericks who ripped into their own party leaders any time they sided with the government, to the delight of journalists and newspaper readers.

Suddenly, thanks to Randolph Churchill, politics was fun again. When Bradlaugh was reelected in spite of being denied his seat, Randolph attacked him again, carefully playing it for laughs and for the gallery and the news media; when the voters of Northampton insisted on returning Bradlaugh again, Randolph did the same thing. And then a fourth and a fifth time: at one point Bradlaugh had to be escorted out of the House chamber by police and locked up in the Big Ben tower. Some people began to joke that Randolph must be bribing Northampton voters to keep voting for Bradlaugh, since they were also keeping Randolph in the headlines.11

Lord Randolph had the good sense to realize that while the Bradlaugh case had launched his political rise, he needed more substantial issues to sustain it. He tried Ireland for a while, taking up the cause of Ulster Protestants in the North and lambasting the Irish nationalists of the south. He tested a new catchphrase, “Tory Democracy,” urging Conservatives to win votes and allies among Britain’s newly enfranchised working class—but the phrase had more headline appeal than substance or thought behind it. He even tried Egypt, furiously denouncing the Liberal government’s support of its corrupt ruler. Finally in the summer of 1884, the man an American journalist called “the political sensation of England” turned to India.

Crucial though India was to the empire, few politicians had any expertise in the empire’s greatest possession. In November 1884 Churchill planned a major tour of India. His friend Wilfred Blunt, who had already traveled widely there, set up the key introductions. He predicted “a great future for any statesman who will preach Tory Democracy in India.”12 Lord Randolph left in December and did not return to London until April 1885, after logging more than 22,800 miles. He then delivered a round of fiery speeches denouncing the Gladstone government’s

* After the Liberals, Tories, and Irish Nationalists.

policies there, from neglecting the threat from Russia to failing to gain more native participation in the Raj. The speeches established him as the Conservatives’ “front line spokesman on India.”13 So when they returned to power in June that year, he was the obvious candidate for secretary of state for India.

In terms of direct influence over people’s lives, it was the single most powerful position in the cabinet, even more powerful than prime minister. At age thirty-six, Randolph Churchill would be overseeing an imperial domain that was, as he discovered in his travels and readings, unique in British history—perhaps unique in human history.

How the British built an empire in India, conquering one of the most ancient and powerful civilizations in the world, is an epic of heroism, sacrifice, ruthlessness, and greed. But it is also the story of a growing sense of mission, even destiny: the growing conviction that the British were meant to rule India not only for their own interests but for the sake of the Indians as well. That belief would decisively shape the character not only of the British Empire in India but also of Randolph’s son Winston Churchill—the man into whose hands the destiny of the Raj would ultimately fall.

Ironically, that empire’s founding fathers, the group of God-fearing merchants living in Shakespeare’s London who created the Honorable East India Company, never intended to go to India at all—any more than Queen Elizabeth I did when she gave them a royal charter on the last day of 1600. Their aim was to get to the Spice Islands (the Molucca Islands in today’s Indonesia), where Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch merchants and adventurers were battling over fortunes in nutmeg, cloves, and mace. The East India Company’s initial stop at Surat, on India’s west coast, was supposed to be only a layover for ventures farther east.

But when the Dutch tortured and murdered ten of their merchants in the island of Amboyne in 1623 and foisted the English out of the Spice Islands, the London-based company had nowhere else to go.14 By 1650, the year John Churchill was born in Devon, the East India Company found itself precariously perched in a tiny settlement near Surat called Fort St. George, doing business at the pleasure of the rulers of India, the Mughal emperors—at the time probably the richest human beings in the world. In 1674 the company acquired a similar outpost at Bombay, which King Charles II had received as a wedding present from the king of Portugal. Then in 1690 it built another, in Bengal at Kalikat, which the English pronounced Calcutta.

Recenzii

“Gandhi & Churchill is a powerful tale of the monumental clash between two of the giants of the twentieth century. Set against the backdrop of war and conflict, this brilliant dual biography of strong-willed visionaries locked in a struggle each believed in makes for compelling reading. Arthur Herman has written a masterful and superbly well researched account of the lives of two men who have had a profound influence on the world in which we live in today that will long stand as a testament to their legacy.”—Carlo D'Este, author of Patton: A Genius For War and Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life

“A fast-paced narrative history…Herman brings to life the twilight of the British Empire and reminds us how the twists and turns of fate helped propel these two men to their places in history. He shows us that there was more common ground between the two than most realize and that the seemingly simple tale of the imperialist and the nationalist is far more nuanced than it seems.” — Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, The Hindustan Times, Bernard Schwartz Fellow, Asia Society

"Cutting through decades of narrow or shallow reporting, Arthur Herman offers a balanced and elegant account which captures both Churchill's generosity of spirit and Gandhi's greatness of soul. While recognizing their faults, he shows what motivated them and made them great—with impressive research that in Churchill's words leaves "no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked." The last two chapters, and the author's Conclusion, are alone worth the price of what must become the standard work on the subject."—Richard M. Langworth, Editor, Finest Hour

“The rivalry between Winston Churchill and Mohandas Gandhi could hardly have been played for higher stakes. The future of British India hung upon the outcome of their 20-year struggle…. As one might expect from the author of To Rule the Waves, a fine history … Mr. Herman has researched Gandhi & Churchill meticulously and written it fluently.”—Wall Street Journal

“An amazingly interesting and perceptive presentation of these two titans of the 20th century…. I learned so much.”—Deirdre Donahue, USA Today’s book reviewer, on the NPR program “On Point”

"A forceful portrait of the emergence of the postcolonial era in the fateful contrast—and surprising affinities—between two historic figures.... Fascinating."—Publishers Weekly

“Herman's book focuses on two imposing figures who epitomized the clash …. he has probed beneath the stereotypes… [and] tells their stories stylishly and eloquently.”—Washington Post Book World

"The perfect summer book...You finish Gandhi & Churchill knowing that you can evaluate the world today, particularly modern India, with more knowledge and insight—USA Today

“Herman's storytelling style is engaging, giving new life to stories we have already heard and even forgotten…. Then there are the surprises…. Provocative, intriguing, even controversial.”—India Today

“Scruplous, compelling, and unfailingly instructive…. A detailed and richly filigreed account that introduces the Anglo-American reader to many facts and vivid if little-known personalities, both English and Indian.” –Commentary

" Brisk narrative flow.... Showing history eluding Gandhi and Churchill, Herman provocatively presents their efforts to shape it."—Booklist

“Exhaustively detailed.”—St. Louis Post-Dispatch

From the Hardcover edition.

“A fast-paced narrative history…Herman brings to life the twilight of the British Empire and reminds us how the twists and turns of fate helped propel these two men to their places in history. He shows us that there was more common ground between the two than most realize and that the seemingly simple tale of the imperialist and the nationalist is far more nuanced than it seems.” — Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, The Hindustan Times, Bernard Schwartz Fellow, Asia Society

"Cutting through decades of narrow or shallow reporting, Arthur Herman offers a balanced and elegant account which captures both Churchill's generosity of spirit and Gandhi's greatness of soul. While recognizing their faults, he shows what motivated them and made them great—with impressive research that in Churchill's words leaves "no stone unturned, no cutlet uncooked." The last two chapters, and the author's Conclusion, are alone worth the price of what must become the standard work on the subject."—Richard M. Langworth, Editor, Finest Hour

“The rivalry between Winston Churchill and Mohandas Gandhi could hardly have been played for higher stakes. The future of British India hung upon the outcome of their 20-year struggle…. As one might expect from the author of To Rule the Waves, a fine history … Mr. Herman has researched Gandhi & Churchill meticulously and written it fluently.”—Wall Street Journal

“An amazingly interesting and perceptive presentation of these two titans of the 20th century…. I learned so much.”—Deirdre Donahue, USA Today’s book reviewer, on the NPR program “On Point”

"A forceful portrait of the emergence of the postcolonial era in the fateful contrast—and surprising affinities—between two historic figures.... Fascinating."—Publishers Weekly

“Herman's book focuses on two imposing figures who epitomized the clash …. he has probed beneath the stereotypes… [and] tells their stories stylishly and eloquently.”—Washington Post Book World

"The perfect summer book...You finish Gandhi & Churchill knowing that you can evaluate the world today, particularly modern India, with more knowledge and insight—USA Today

“Herman's storytelling style is engaging, giving new life to stories we have already heard and even forgotten…. Then there are the surprises…. Provocative, intriguing, even controversial.”—India Today

“Scruplous, compelling, and unfailingly instructive…. A detailed and richly filigreed account that introduces the Anglo-American reader to many facts and vivid if little-known personalities, both English and Indian.” –Commentary

" Brisk narrative flow.... Showing history eluding Gandhi and Churchill, Herman provocatively presents their efforts to shape it."—Booklist

“Exhaustively detailed.”—St. Louis Post-Dispatch

From the Hardcover edition.

Premii

- Audies Winner, 2009