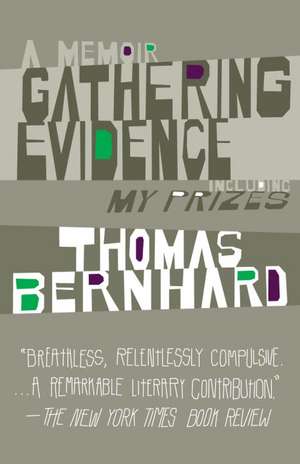

Gathering Evidence/My Prizes

Autor Thomas Bernharden Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 oct 2011

Born in 1931, the illegitimate child of an abandoned mother, Thomas Bernhard was brought up by an eccentric grandmother and an adored grandfather in right-wing, Catholic Austria. He ran away from home at age fifteen. Three years later, he contracted pneumonia and was placed in a hospital ward for the old and terminally ill, where he observed first-hand—and with unflinching acuity—the cruel nature of protracted suffering and death. From the age of twenty-one, everything he wrote was shaped by the urgency of a dying man’s testament—and where this account of his life ends, his art begins.

Included in this edition is My Prizes, a collection of Bernhard’s viciously funny and revelatory essays on his later literary life. Here is a portrait of the artist as a prize-winner: laconic, sardonic, shaking his head with biting amusement at the world and at himself.

Preț: 99.83 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 150

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.10€ • 19.82$ • 15.97£

19.10€ • 19.82$ • 15.97£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400077625

ISBN-10: 1400077621

Pagini: 408

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1400077621

Pagini: 408

Dimensiuni: 135 x 204 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Thomas Bernhard was born in Holland in 1931 and grew up in Austria. He studied music at the Akademie Mozarteum in Salzburg. In 1957 he began a second career, as a playwright, poet, and novelist. The winner of the three most distinguished and coveted literary prizes awarded in Germany, he has become one of the most widely translated and admired writers of his generation. He published nine novels, an autobiography, one volume of poetry, four collections of short stories, and six volumes of plays. Thomas Bernhard died in Austria in 1989.

Extras

The Grillparzer Prize

For the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna I had to buy a suit, as I had suddenly realized two hours before the presentation that I couldn’t appear at this doubtless extraordinary ceremony in trousers and a pullover, and so I had actually made the decision on the so-called Graben to go to the Kohlmarkt and outfit myself with appropriate formality, to which end, based on previous shopping for socks on several occasions, I picked the best-known gentleman’s outfitters with the descriptive name Sir Anthony, if I remember correctly it was nine forty-five when I went into Sir Anthony’s salon, the award ceremony for the Grillparzer Prize was at eleven, so I had plenty of time. I intended to buy myself the best pure-wool suit in anthracite, even if it was off the peg, with matching socks, a tie, and an Arrow shirt in fine cloth, striped gray and blue. The difficulty of initially making oneself understood in the so-called finer emporiums is well-known, even if the customer immediately says what he’s looking for in the most concise terms, at first he’ll be stared at incredulously until he repeats what he wants. But naturally the salesman he’s talking to hasn’t taken it in yet. So it took longer than it need have that time in Sir Anthony to be led to the relevant racks. In fact the arrangement of this shop was already familiar to me from buying socks there and I myself knew better than the salesman where to find the suit I was looking for. I walked over to the rack with the suits in question and pointed to one particular example, which the salesman took down from the rod to hold up for my inspection. I checked the quality of the material and even tried it on in the dressing room. I bent forward several times and leaned back and found that the trousers fit. I put on the jacket, turned around several times in front of the mirror, raised my arms and lowered them again, the jacket fit like the trousers. I walked around the shop in the suit a little bit, and took the opportunity to find the shirt and the socks. Finally I said I would keep the suit on, and I also wanted to put on the shirt and the socks. I found a tie, put it on, tightened it as much as I could, inspected myself once more in the mirror, paid, and went out. They had packed my old trousers and pullover in a bag with “Sir Anthony” on it, so with this bag in my hand, I crossed the Kohlmarkt to meet my aunt, with whom I was going to rendezvous in the Gerstner Restaurant on the Kärnterstrasse, up on the second floor. We wanted to eat a sandwich in order to forestall any malaise or even fainting episode during the proceedings. My aunt had already been to Gerstner’s, she had already classified my sartorial transformation as acceptable, and uttered her famous well, all right. Until this moment I hadn’t worn a suit for years, yes until then I had always appeared in nothing but trousers and pullover, even to the theater if I went at all, I only went in trousers and pullover, mainly in gray wool trousers and a bright red, coarse-knit sheep’s-wool pullover that a well-disposed American had given me right after the war. In this outfit, I remember, I had traveled to Venice several times and gone to the famous theater at La Fenice, once to a production of Monteverdi’s Tancredi directed by Vittorio Gui, and I had been with these trousers and pullover in Rome, in Palermo, in Taormina, and in Florence, and in almost all the other capitals of Europe, apart from the fact that I have almost always worn these articles of clothing at home, the shabbier the trousers and pullover, the more I loved them, for years people only saw me in these trousers and this pullover, I’ve worn these pieces of clothing for more than a quarter of a century. Suddenly, on the Graben as I said and two hours before the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize, I found these pieces of clothing, which had grown in these decades to be a second skin, to be unsuitable for an honor connected with the name Grillparzer which would take place in the Academy of Sciences. Sitting down in the Gerstner I suddenly had the feeling the trousers were too tight for me, I thought it’s probably the way all new trousers feel, and the jacket suddenly felt too tight and also as regards the jacket, I thought this is normal. I ordered a sandwich and drank a glass of beer with it. So who had won this so-called Grillparzer Prize before me, asked my aunt, and for the moment the only name that came to me was Gerhart Hauptmann, I’d read that once and that was the occasion I learned of the existence of the Grillparzer Prize for the first time. The prize is not awarded regularly, only on a case-by-case basis, I said, and I thought that it was now six or seven years between awards, maybe sometimes only five, I didn’t know exactly, I still don’t know today. Also this awarding of the prize was naturally making me nervous and I tried to distract myself and my aunt from the fact that there was only half an hour before the ceremony began, I described the outrageousness of my deciding on the Graben to buy a suit for the ceremony and that it had been self-evident that I would find the shop on the Kohlmarkt which stocks English suits by Chester Barry and Burberry. Why, I had asked myself again, shouldn’t I buy a top-quality suit, even if it is off the peg, and now the suit I was wearing was a suit made by Barry. My aunt again only focused on the material and was happy with the English quality. Again she said her famous well, all right. About the cut, nothing. It was classic. She was very happy about the fact that the Academy of Sciences was awarding me that Grillparzer Prize today, she said, and proud, but more happy than proud, and she got to her feet and I followed her out of the Gerstner and down onto the street. We had only a few steps to walk to the Academy of Sciences. The bag with “Sir Anthony” on it had become deeply repellent to me, but I couldn’t change things. I’ll hand over the bag before going into the Academy of Sciences, I thought. Some friends who didn’t want to miss me being honored were also on their way, we met them in the entrance hall of the Academy. A lot of people were already gathered there and it looked as if the hall was already full. The friends left us in peace and we looked around the hall for some important person to greet us. I walked up and down the entrance hall of the Academy several times with my aunt, but nobody took even the slightest notice of us. So let’s go in, I said, and thought, inside the hall some important person will greet me and lead me to the appropriate place with my aunt. Everything in the hall indicated tremendous festiveness and I literally had the sensation that my knees were trembling. My aunt, too, kept looking, as I did, for an important person to greet us. In vain. So we simply stood in the entrance to the hall and waited. But people were pushing past us and kept bumping into us and we had to recognize that we had chosen the least suitable place to wait. Well, is no one going to receive us? we thought. We looked around. The hall was already just about packed and all for the sole purpose of my being awarded the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences, I thought. And no one is greeting me and my aunt. At the age of eighty-one she looked wonderful, elegant, intelligent, and in these moments she seemed to be brave as never before. Now various musicians from the Philharmonic had also taken their places at the front of the podium and everything was pointing to the beginning of the ceremony. But not one person had taken any notice of us, who were supposed to be the centerpiece. So I suddenly had an idea: we’ll just go in, I said to my aunt, and sit in the middle of the hall where there are still a few free seats, and we’ll wait. We went into the hall and found those free seats in the middle of the hall, many people had to stand and complained to us as we forced our way past them. So now we were sitting in the tenth or eleventh row in the middle of the hall of the Academy of Sciences and we waited. All the so-called guests of honor had now taken their places. But of course the ceremony didn’t begin. And only I and my aunt knew why. Up front on the podium at ever-decreasing intervals excited gentlemen were running this way and that as if they were looking for something, namely me. The running this way and that by the gentlemen on the podium went on for a while, during which unrest was already breaking out in the hall. In the meantime the Minister for Sciences had arrived and taken her seat in the front row. She was greeted by the President of the Academy, whose name was Hunger, and led to her chair. A whole line of other so-called dignitaries who were unknown to me were greeted and led to the first or second row. Suddenly I saw a gentleman on the podium whisper something into the ear of another gentleman while simultaneously pointing into the tenth or eleventh row with an outstretched hand, I was the only one who knew he was pointing at me. What happened next is as follows: The gentleman who had whispered something into the ear of the other gentleman and pointed at me went down into the hall and right to my row and made his way along to me. Yes, he said, why are you sitting here when you’re the most important person in this celebration and not up front in the first row where we, he actually said we, where we have reserved two places for you and your companion? Yes, why? he asked again and it seemed as if all eyes in the hall were on me and the gentleman. The President, said the gentleman, is asking you please to come to the front, so please come to the front, your seat is right next to the Minister, Herr Bernhard. Yes I said if it’s that simple, but naturally I will only go into the first row if President Hunger has requested me personally to do so, it goes without saying only if President Hunger is inviting me personally to do so. My aunt said nothing during this scene and the guests of the ceremony all looked at us and the gentleman went back along the whole row and then toward the front and whispered something from beside the Minister into President Hunger’s ear. After this there was much unrest in the hall, only the tuning-up by the players from the Philharmonic stopped it from becoming something really ugly and I saw that President Hunger was laboriously making his way toward me. Now is the time to stand firm, I thought, demonstrate my intransigence, courage, single-mindedness. I’m not going to go and meet them, I thought, just as (in the deepest sense of the word) they didn’t meet me. When President Hunger reached me, he said he was sorry, what he was sorry for, he didn’t say. Please would I be kind enough to come with my aunt to the front row, my seat and my aunt’s were between the Minister and him. So my aunt and I followed President Hunger into the front row. When we had sat down and an indefinable murmur had spread throughout the hall, the ceremony could begin. I think the men from the Philharmonic played a piece by Mozart. Then there were several longer or shorter speeches about Grillparzer. The one time I glanced over at Minister Firnberg, that was her name, she had fallen asleep, which hadn’t escaped President Hunger either, for the Minister was snoring, even if very quietly, she was snoring, she was snoring the quiet, world-famous ministerial snore. My aunt was following the so-called ceremony with the greatest attention, when some turn of phrase in one of the speeches sounded too stupid or even too comical, she gave me a complicit glance. The two of us were having our own experience. Finally, after about an hour and a half, President Hunger stood up and went to the podium and announced the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize to me. He read out a few words of praise about my work, not without naming some titles of plays that were supposed to be by me but which I hadn’t actually written, and listed a row of European famous names who had been singled out for the prize before me. Herr Bernhard was receiving the prize for his play A Feast for Boris, said Hunger (the play that had been appallingly badly acted a year before by the Burgtheater company in the Academy Theater), and then, as if to embrace me, he opened his arms wide. The signal for me to step onto the podium had arrived. I stood up and went to Hunger. He shook my hand and gave me a so-called award certificate of a tastelessness, like every other award certificate I have ever received, that was beyond comparison. I hadn’t intended to say anything on the podium, I hadn’t been asked to do so at all. So in order to choke off my embarrassment, I said a brief Thank you! and went back down into the hall and sat down. Whereupon Herr Hunger also sat down and the musicians from the Philharmonic played a piece by Beethoven. While the musicians from the Phil- harmonic were playing, I thought over the entire ceremony now ending, whose peculiarity and tastelessness and mindlessness naturally had not yet had the chance to register in my consciousness. The musicians from the Philharmonic had barely finished playing when up stood Minister Firnberg and, immediately, President Hunger and both of them went to the podium. Now everyone in the hall had stood up and was pushing toward the podium, toward the Minister naturally and President Hunger who was talking to the Minister. I stood with my aunt, dumbfounded and increasingly at a loss, and we listened to the rising hubbub of a myriad of voices. After a time the Minister looked around and asked in a voice in which inimitable arrogance competed with stupidity: So, where is the little poet? I had been standing right next to her but I didn’t dare to make myself known. I took my aunt and we left the hall. Unhindered and without a single person having taken any notice of us, we left the Academy of Sciences at around one o’clock. Outside, friends were waiting for us. With these friends, we went to have lunch in the place called the Gösser Bierklinik. A philosopher, an architect, their wives, and my brother. All entertaining people. I no longer remember what we ate. When I was asked during the meal how large the prize money was, it was the first time I really took in the fact that the prize had no money attached to it at all. My own humiliation then struck me as common impudence. But it’s one of the greatest honors that can be bestowed on an Austrian, to receive the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences, said someone at the table, I think it was the architect. It was huge, said the philosopher. My brother, as always on such occasions, said nothing. After the meal I suddenly had the feeling that the newly bought suit was far too tight and went into the shop on the Kohlmarkt, Sir Anthony I mean, and said to them in a fairly brash way but still with perfect politeness that I wished to exchange the suit, I had just bought the suit, as they knew, but it was at least one size too small. It was my firmness that made the salesman I was speaking to go straight to the rack from which my suit had come. Without objection he let me slip into the same suit but one size larger and I immediately felt that this suit fit. How could I have thought only a few hours ago that the one-size-smaller suit fit me? I clutched my head. Now I was wearing the suit that actually fit and I left the shop with the greatest sense of relief. Whoever buys the suit I have just returned, I thought, has no idea that it’s been with me at the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna. It was an absurd thought, and at this absurd thought I took heart. I spent a most enjoyable day with my aunt and we kept laughing over the people at Sir Anthony, who had let me exchange my suit without objections, although I had already worn it to the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize in the Academy of Sciences. That they were so obliging is something about the people in Sir Anthony in the Kohlmarkt that I shall never forget.

For the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna I had to buy a suit, as I had suddenly realized two hours before the presentation that I couldn’t appear at this doubtless extraordinary ceremony in trousers and a pullover, and so I had actually made the decision on the so-called Graben to go to the Kohlmarkt and outfit myself with appropriate formality, to which end, based on previous shopping for socks on several occasions, I picked the best-known gentleman’s outfitters with the descriptive name Sir Anthony, if I remember correctly it was nine forty-five when I went into Sir Anthony’s salon, the award ceremony for the Grillparzer Prize was at eleven, so I had plenty of time. I intended to buy myself the best pure-wool suit in anthracite, even if it was off the peg, with matching socks, a tie, and an Arrow shirt in fine cloth, striped gray and blue. The difficulty of initially making oneself understood in the so-called finer emporiums is well-known, even if the customer immediately says what he’s looking for in the most concise terms, at first he’ll be stared at incredulously until he repeats what he wants. But naturally the salesman he’s talking to hasn’t taken it in yet. So it took longer than it need have that time in Sir Anthony to be led to the relevant racks. In fact the arrangement of this shop was already familiar to me from buying socks there and I myself knew better than the salesman where to find the suit I was looking for. I walked over to the rack with the suits in question and pointed to one particular example, which the salesman took down from the rod to hold up for my inspection. I checked the quality of the material and even tried it on in the dressing room. I bent forward several times and leaned back and found that the trousers fit. I put on the jacket, turned around several times in front of the mirror, raised my arms and lowered them again, the jacket fit like the trousers. I walked around the shop in the suit a little bit, and took the opportunity to find the shirt and the socks. Finally I said I would keep the suit on, and I also wanted to put on the shirt and the socks. I found a tie, put it on, tightened it as much as I could, inspected myself once more in the mirror, paid, and went out. They had packed my old trousers and pullover in a bag with “Sir Anthony” on it, so with this bag in my hand, I crossed the Kohlmarkt to meet my aunt, with whom I was going to rendezvous in the Gerstner Restaurant on the Kärnterstrasse, up on the second floor. We wanted to eat a sandwich in order to forestall any malaise or even fainting episode during the proceedings. My aunt had already been to Gerstner’s, she had already classified my sartorial transformation as acceptable, and uttered her famous well, all right. Until this moment I hadn’t worn a suit for years, yes until then I had always appeared in nothing but trousers and pullover, even to the theater if I went at all, I only went in trousers and pullover, mainly in gray wool trousers and a bright red, coarse-knit sheep’s-wool pullover that a well-disposed American had given me right after the war. In this outfit, I remember, I had traveled to Venice several times and gone to the famous theater at La Fenice, once to a production of Monteverdi’s Tancredi directed by Vittorio Gui, and I had been with these trousers and pullover in Rome, in Palermo, in Taormina, and in Florence, and in almost all the other capitals of Europe, apart from the fact that I have almost always worn these articles of clothing at home, the shabbier the trousers and pullover, the more I loved them, for years people only saw me in these trousers and this pullover, I’ve worn these pieces of clothing for more than a quarter of a century. Suddenly, on the Graben as I said and two hours before the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize, I found these pieces of clothing, which had grown in these decades to be a second skin, to be unsuitable for an honor connected with the name Grillparzer which would take place in the Academy of Sciences. Sitting down in the Gerstner I suddenly had the feeling the trousers were too tight for me, I thought it’s probably the way all new trousers feel, and the jacket suddenly felt too tight and also as regards the jacket, I thought this is normal. I ordered a sandwich and drank a glass of beer with it. So who had won this so-called Grillparzer Prize before me, asked my aunt, and for the moment the only name that came to me was Gerhart Hauptmann, I’d read that once and that was the occasion I learned of the existence of the Grillparzer Prize for the first time. The prize is not awarded regularly, only on a case-by-case basis, I said, and I thought that it was now six or seven years between awards, maybe sometimes only five, I didn’t know exactly, I still don’t know today. Also this awarding of the prize was naturally making me nervous and I tried to distract myself and my aunt from the fact that there was only half an hour before the ceremony began, I described the outrageousness of my deciding on the Graben to buy a suit for the ceremony and that it had been self-evident that I would find the shop on the Kohlmarkt which stocks English suits by Chester Barry and Burberry. Why, I had asked myself again, shouldn’t I buy a top-quality suit, even if it is off the peg, and now the suit I was wearing was a suit made by Barry. My aunt again only focused on the material and was happy with the English quality. Again she said her famous well, all right. About the cut, nothing. It was classic. She was very happy about the fact that the Academy of Sciences was awarding me that Grillparzer Prize today, she said, and proud, but more happy than proud, and she got to her feet and I followed her out of the Gerstner and down onto the street. We had only a few steps to walk to the Academy of Sciences. The bag with “Sir Anthony” on it had become deeply repellent to me, but I couldn’t change things. I’ll hand over the bag before going into the Academy of Sciences, I thought. Some friends who didn’t want to miss me being honored were also on their way, we met them in the entrance hall of the Academy. A lot of people were already gathered there and it looked as if the hall was already full. The friends left us in peace and we looked around the hall for some important person to greet us. I walked up and down the entrance hall of the Academy several times with my aunt, but nobody took even the slightest notice of us. So let’s go in, I said, and thought, inside the hall some important person will greet me and lead me to the appropriate place with my aunt. Everything in the hall indicated tremendous festiveness and I literally had the sensation that my knees were trembling. My aunt, too, kept looking, as I did, for an important person to greet us. In vain. So we simply stood in the entrance to the hall and waited. But people were pushing past us and kept bumping into us and we had to recognize that we had chosen the least suitable place to wait. Well, is no one going to receive us? we thought. We looked around. The hall was already just about packed and all for the sole purpose of my being awarded the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences, I thought. And no one is greeting me and my aunt. At the age of eighty-one she looked wonderful, elegant, intelligent, and in these moments she seemed to be brave as never before. Now various musicians from the Philharmonic had also taken their places at the front of the podium and everything was pointing to the beginning of the ceremony. But not one person had taken any notice of us, who were supposed to be the centerpiece. So I suddenly had an idea: we’ll just go in, I said to my aunt, and sit in the middle of the hall where there are still a few free seats, and we’ll wait. We went into the hall and found those free seats in the middle of the hall, many people had to stand and complained to us as we forced our way past them. So now we were sitting in the tenth or eleventh row in the middle of the hall of the Academy of Sciences and we waited. All the so-called guests of honor had now taken their places. But of course the ceremony didn’t begin. And only I and my aunt knew why. Up front on the podium at ever-decreasing intervals excited gentlemen were running this way and that as if they were looking for something, namely me. The running this way and that by the gentlemen on the podium went on for a while, during which unrest was already breaking out in the hall. In the meantime the Minister for Sciences had arrived and taken her seat in the front row. She was greeted by the President of the Academy, whose name was Hunger, and led to her chair. A whole line of other so-called dignitaries who were unknown to me were greeted and led to the first or second row. Suddenly I saw a gentleman on the podium whisper something into the ear of another gentleman while simultaneously pointing into the tenth or eleventh row with an outstretched hand, I was the only one who knew he was pointing at me. What happened next is as follows: The gentleman who had whispered something into the ear of the other gentleman and pointed at me went down into the hall and right to my row and made his way along to me. Yes, he said, why are you sitting here when you’re the most important person in this celebration and not up front in the first row where we, he actually said we, where we have reserved two places for you and your companion? Yes, why? he asked again and it seemed as if all eyes in the hall were on me and the gentleman. The President, said the gentleman, is asking you please to come to the front, so please come to the front, your seat is right next to the Minister, Herr Bernhard. Yes I said if it’s that simple, but naturally I will only go into the first row if President Hunger has requested me personally to do so, it goes without saying only if President Hunger is inviting me personally to do so. My aunt said nothing during this scene and the guests of the ceremony all looked at us and the gentleman went back along the whole row and then toward the front and whispered something from beside the Minister into President Hunger’s ear. After this there was much unrest in the hall, only the tuning-up by the players from the Philharmonic stopped it from becoming something really ugly and I saw that President Hunger was laboriously making his way toward me. Now is the time to stand firm, I thought, demonstrate my intransigence, courage, single-mindedness. I’m not going to go and meet them, I thought, just as (in the deepest sense of the word) they didn’t meet me. When President Hunger reached me, he said he was sorry, what he was sorry for, he didn’t say. Please would I be kind enough to come with my aunt to the front row, my seat and my aunt’s were between the Minister and him. So my aunt and I followed President Hunger into the front row. When we had sat down and an indefinable murmur had spread throughout the hall, the ceremony could begin. I think the men from the Philharmonic played a piece by Mozart. Then there were several longer or shorter speeches about Grillparzer. The one time I glanced over at Minister Firnberg, that was her name, she had fallen asleep, which hadn’t escaped President Hunger either, for the Minister was snoring, even if very quietly, she was snoring, she was snoring the quiet, world-famous ministerial snore. My aunt was following the so-called ceremony with the greatest attention, when some turn of phrase in one of the speeches sounded too stupid or even too comical, she gave me a complicit glance. The two of us were having our own experience. Finally, after about an hour and a half, President Hunger stood up and went to the podium and announced the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize to me. He read out a few words of praise about my work, not without naming some titles of plays that were supposed to be by me but which I hadn’t actually written, and listed a row of European famous names who had been singled out for the prize before me. Herr Bernhard was receiving the prize for his play A Feast for Boris, said Hunger (the play that had been appallingly badly acted a year before by the Burgtheater company in the Academy Theater), and then, as if to embrace me, he opened his arms wide. The signal for me to step onto the podium had arrived. I stood up and went to Hunger. He shook my hand and gave me a so-called award certificate of a tastelessness, like every other award certificate I have ever received, that was beyond comparison. I hadn’t intended to say anything on the podium, I hadn’t been asked to do so at all. So in order to choke off my embarrassment, I said a brief Thank you! and went back down into the hall and sat down. Whereupon Herr Hunger also sat down and the musicians from the Philharmonic played a piece by Beethoven. While the musicians from the Phil- harmonic were playing, I thought over the entire ceremony now ending, whose peculiarity and tastelessness and mindlessness naturally had not yet had the chance to register in my consciousness. The musicians from the Philharmonic had barely finished playing when up stood Minister Firnberg and, immediately, President Hunger and both of them went to the podium. Now everyone in the hall had stood up and was pushing toward the podium, toward the Minister naturally and President Hunger who was talking to the Minister. I stood with my aunt, dumbfounded and increasingly at a loss, and we listened to the rising hubbub of a myriad of voices. After a time the Minister looked around and asked in a voice in which inimitable arrogance competed with stupidity: So, where is the little poet? I had been standing right next to her but I didn’t dare to make myself known. I took my aunt and we left the hall. Unhindered and without a single person having taken any notice of us, we left the Academy of Sciences at around one o’clock. Outside, friends were waiting for us. With these friends, we went to have lunch in the place called the Gösser Bierklinik. A philosopher, an architect, their wives, and my brother. All entertaining people. I no longer remember what we ate. When I was asked during the meal how large the prize money was, it was the first time I really took in the fact that the prize had no money attached to it at all. My own humiliation then struck me as common impudence. But it’s one of the greatest honors that can be bestowed on an Austrian, to receive the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences, said someone at the table, I think it was the architect. It was huge, said the philosopher. My brother, as always on such occasions, said nothing. After the meal I suddenly had the feeling that the newly bought suit was far too tight and went into the shop on the Kohlmarkt, Sir Anthony I mean, and said to them in a fairly brash way but still with perfect politeness that I wished to exchange the suit, I had just bought the suit, as they knew, but it was at least one size too small. It was my firmness that made the salesman I was speaking to go straight to the rack from which my suit had come. Without objection he let me slip into the same suit but one size larger and I immediately felt that this suit fit. How could I have thought only a few hours ago that the one-size-smaller suit fit me? I clutched my head. Now I was wearing the suit that actually fit and I left the shop with the greatest sense of relief. Whoever buys the suit I have just returned, I thought, has no idea that it’s been with me at the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize of the Academy of Sciences in Vienna. It was an absurd thought, and at this absurd thought I took heart. I spent a most enjoyable day with my aunt and we kept laughing over the people at Sir Anthony, who had let me exchange my suit without objections, although I had already worn it to the awarding of the Grillparzer Prize in the Academy of Sciences. That they were so obliging is something about the people in Sir Anthony in the Kohlmarkt that I shall never forget.

Recenzii

“Breathless, relentlessly compulsive. . . . A remarkable literary contribution.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“One of the most powerful autobiographies of the 20th century. . . . Overwhelming in its impact.”

—Los Angeles Times

“A searing and utterly extraordinary memoir. . . . Unflinching, resonant and simply important. . . . The book is magnificent in every sentence.”

—Claire Messud, Newsday

“Vehement and fascinating. . . . Arguably his finest work.”

—The Washington Post

—The New York Times Book Review

“One of the most powerful autobiographies of the 20th century. . . . Overwhelming in its impact.”

—Los Angeles Times

“A searing and utterly extraordinary memoir. . . . Unflinching, resonant and simply important. . . . The book is magnificent in every sentence.”

—Claire Messud, Newsday

“Vehement and fascinating. . . . Arguably his finest work.”

—The Washington Post