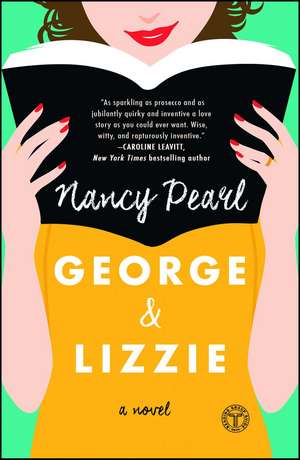

George and Lizzie: A Novel

Autor Nancy Pearlen Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 ian 2019

George and Lizzie are a couple, meeting as college students and marrying soon after graduation, but no one would ever describe them of being soulmates. George grew up in a warm and loving family—his father an orthodontist, his mother a stay-at-home mom—while Lizzie was the only child of two famous psychologists, who viewed her more as an in-house experiment than a child to love.

After a decade of marriage, nothing has changed—George is happy; Lizzie remains…unfulfilled. But when George discovers that Lizzie has been searching for the whereabouts of an old boyfriend, Lizzie is forced to decide what love means to her, what George means to her, and whether her life with George is the one she wants.

With pitch-perfect prose and compassion and humor to spare, George and Lizzie is “a richly absorbing portrait of a perfectly imperfect marriage,” (Amy Poeppel, author of Small Admissions), and “a story of forgiveness, especially for one’s self” (The Washington Post).

Preț: 99.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

18.97€ • 19.73$ • 15.89£

18.97€ • 19.73$ • 15.89£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20 februarie-06 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781501162909

ISBN-10: 150116290X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

ISBN-10: 150116290X

Pagini: 304

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Touchstone Publishing

Colecția Touchstone

Notă biografică

Nancy Pearl is known as “America’s Librarian.” She speaks about the pleasures of reading at library conferences, to literacy organizations and community groups throughout the world and comments on books regularly on NPR’s Morning Edition. Born and raised in Detroit, she received her master’s degree in library science in 1967 from the University of Michigan. She also received an MA in history from Oklahoma State University in 1977. Among her many honors and awards are the 2011 Librarian of the Year Award from Library Journal; and the 2011 Lifetime Achievement Award from the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association. She also hosts a monthly television show, Book Lust with Nancy Pearl. She lives in Seattle with her husband.

Extras

George and Lizzie

The boys who played defense were much less interesting to Lizzie than the offense had been. After all, defense had originally been Andrea’s bailiwick, and Lizzie had decided to go on with the Great Game only after finishing with the offense in a badly mistaken desire to complete what she’d started. Honestly, those eleven defensive players are mostly blurred together in her mind.

The two cornerbacks were Micah Delavan and Mitchell Oberski. They were inseparable and together known as the M&M’s. Micah only had four fingers on his left hand, while Mitchell had a large birthmark the shape of Wyoming on his back. The two of them went off to college together and as far as Lizzie knew they were together still.

That she can’t bring herself to tell George about Jack.

That she can’t bring herself to tell George about the shame of the Great Game.

That she never should have told Jack she was the girl in the Psychology Today article, because that was why he left her and never came back.

That she is a too-easy weeper. Lizzie understands this to be a reaction to the fact that Mendel and Lydia became furious when, as a child, she cried. What sort of parents refuse to let their child cry? Unfortunately, the sort that gave birth to, and raised, Elizabeth Frieda Bultmann Goldrosen, that’s who.

That she always, always either loses one of a pair of earrings or gets an ineradicable stain on a white shirt.

That she looks exactly like Mendel, if Mendel were female, although she supposes that it’s better than looking like the witch Lydia.

That she’s failed so miserably in so many different parts of her life.

That she is the same rotten housekeeper that her mother was. George was the total opposite. He could walk into a room, give it a stern glance, and it immediately resolved itself into neatness: the books lie attractively on the coffee table, the magazines arrange themselves in a pile from oldest down to newest; and the dust bunnies cast themselves into the air and disappear. On the other hand, when Lizzie walks into a room, chaos ensues. No matter how hard she tries, the room remains a mess. George counseled patience (he pretty much always counseled patience), advising her to vacuum more carefully, to take her time and do one thing to completion at a time. This was very hard, not to say impossible, for Lizzie to accomplish. She hated herself for this thought but secretly wished that George had some grad students that she could co-opt to clean their house.

December 21

Part of the Goldrosen tradition was that George always came home on the twenty-first of December and flew back early on the twenty-sixth. For Lizzie, the day they left Ann Arbor proved frustrating in the extreme. Already nervous and regretting her decision to accompany George home, she twice came close to bolting from her seat while they were waiting for their flight and finding her own way home. Nothing that happened on the trip down to Tulsa boded well, in her opinion, for future trips to Tulsa (and she was right; their Christmas flights never went particularly smoothly). Their plane out of Metro Airport departed late because a fierce storm over Lake Michigan caused whiteout conditions at O’Hare, so they missed their connection in Chicago and were rerouted via Salt Lake City, which involved an endless stay in a terminal that Lizzie thought resembled a waiting room for long-haul buses. Of course George was perfectly content. He read old issues of the Journal of the American Dental Association, fascinated by the intricacies of veneers, tooth decay, implants, and whether or not a dentist had a moral, if not legal, obligation to report suspected child abuse. Although Lizzie’d brought a novel with her (Barbara Kingsolver’s The Bean Trees), she couldn’t sit still long enough to open it and begin reading. Instead she paced.

Lizzie hated waiting for anything: she became bored and edgy, inclined to snap at everyone around, even strangers. She walked around the terminal, growing more upset by the minute. At first she tried to decide if she’d made the right decision by coming with George. She wondered what Jack would say if he knew what she was doing. She wondered if she knew what she was doing. Meeting Mendel and not meeting Lydia at Thanksgiving hadn’t sent George scurrying out of her life. He didn’t exactly enjoy Thanksgiving dinner with the Bultmann family (what sane person would?), but he didn’t give up on Lizzie as a result. She sort of wished that Jack had come home with her sometime that spring they were together; maybe that would have helped him understand her better.

All this thinking about the present, the past, and the future was exhausting. By the time they finally landed in Tulsa, Lizzie was worn-out, hungry, wired from drinking too many Cokes in the Salt Lake airport and too much coffee on the plane. She’d had it with the weather gods and (unfairly—it was mostly unfair to blame George for much of anything; Lizzie knew this, but it didn’t prevent her from doing so) with George for dragging her to Oklahoma. George was simply glad they’d finally arrived. Now his parents could meet Lizzie.

Elaine and Allan were waiting for them at the gate. They took turns hugging George and Lizzie. “We’re so happy you’re here,” Allan told them.

Lizzie tried not to smile too widely, wondering if either of George’s parents noticed that one of her incisors was slightly crooked.

“Lizzie,” Elaine said, hugging her again, “we’re just thrilled to finally meet you. It’s lovely that you came home with George. He’s told us so much about you.” Lizzie tried not to pull away from Elaine too quickly, but she was, sadly, too much of a Bultmann, used to Bultmann pseudo-hugs, to feel comfortable in Elaine’s embrace.

“I’m glad to be here too,” she managed to say.

“George, you and Dad wait for the suitcases in baggage claim, and we’ll meet you at the car.”

“George’s told me a lot about your family’s Christmases,” Lizzie said as they walked. Walking to the car! This was like a toy airport compared to Detroit’s.

“We do have a ton of family traditions,” Elaine admitted. “Some of them go back to my childhood, but mostly they’re things we’ve just come up with since the boys were babies. I love this time of year. You’ll see. It’s sort of sad that the days just whiz by.”

Just at the moment, days whizzing by sounded good to Lizzie.

“Oh, here they come. Good. You both must be starving. Let’s hurry and get you home.”

The Goldrosens’ house was at the end of a cul-de-sac. It was redbrick, two-storied, stately, and serene. It looked only a little smaller than the Kappa house in Ann Arbor. It looked nothing at all like the house where Lizzie grew up. “I’ve put you in the bedroom that’s directly across the hall from George,” Elaine said. “Let’s get your luggage upstairs, and as soon as you come down we can eat. It’s just so lovely that you’re here,” she repeated. “I wish Todd had come home. Australia’s so far away. It’s always so nice to be together on holidays, especially Christmas.”

The Goldrosen traditions turned out to be many and various. Throughout them all, Lizzie tried to look happy and as though she were enjoying everything. This was mostly not very difficult, although at night her jaw ached from smiling. She would recall that first Christmas visit much later, when she’d go to parties honoring George and have to appear to be having a good time in that same determined way in front of his devoted fans and avid followers.

December 22

Right after a sumptuous breakfast that included bagels (which arrived via FedEx, every week, from the St. Viateur Bagel Shop in Montreal. “These are the bagels I grew up with,” Elaine told Lizzie. “I think they’re so much better than the ones everyone raves about in New York”), cream cheese, lox, tomatoes, Swiss cheese, and red onions, George and his father left to go to Allan’s office so he could show George all the latest equipment and generally talk teeth.

Lizzie and Elaine sat down at the kitchen table and began blowing out the insides of twenty-four eggs. Lizzie discovered that it was much more difficult than it sounded. First Elaine showed her how to poke a hole in each end of the egg. “You have to begin with a sharp needle to pierce the shell, then gradually make the holes a little larger. Sometimes a darning needle works better for that part, but you have to be careful not to break the egg.”

It took her about half an hour, from first tentative needle jab to the empty shell, per egg. Elaine, with her years of practice behind her, was much faster. Somehow she’d never thought of the insides of eggs before, or at least not in quite the same way as she saw them now.

She felt embarrassed and clumsy because she’d smashed three eggs in the process, but Elaine didn’t seem to notice, or in any event, didn’t comment on it. The resulting mixture—a bowl of egg whites and yolks—looked so disgusting that Lizzie decided she might have to give up eating eggs until the memory of the contents of that bowl blurred a lot.

Once the eggs were empty, Elaine brought out a big cardboard box filled with ribbons, crepe paper, scraps of felt and other material, construction paper, Magic Markers, and glue sticks, along with several large jars of paste. It was everything they might need or want to use to decorate the eggs. They gave them faces, pasting on bits of felt that they cut into shapes for the eyes, nose, mouth, and eyebrows, and followed that up by attaching yellow, red, black, or brown yarn for hair. Sometimes they braided the yarn, and sometimes put it into a ponytail using a contrasting piece of yarn to tie it up. Despite her feeling she was doing something wrong, or not living up to Elaine’s expectations, Lizzie felt pretty relaxed. “I was awful in art in elementary school,” Lizzie told her. “But this is really fun.”

They attached pipe cleaners to make arms and legs (another job that required a very light touch; Lizzie broke three more eggs and Elaine one) and finally they concocted dresses made out of the crepe paper.

“This is a paste-intensive job, isn’t it,” she commented to Elaine, looking at her encrusted nails.

“You bet. I think this whole holiday season is the only thing that keeps Elmer’s in business. Oh, and nursery schools, of course. But wait until tomorrow: there’s lots more paste still to come.”

Later in the day Elaine and Lizzie carefully unwrapped from layers of tissue paper the almost two dozen dolls that Elaine had created in Christmases past. “I mostly give the dolls away, but I always keep my favorite for the top of the tree. I’m saving them for my granddaughters, if Todd or George ever gets married and produces female children.”

They then began baking dozens and dozens of cookies for the family to eat and to give as gifts to friends. The word “friends” encompassed Wade, the FedEx driver, the mailman (despite his obvious and obnoxious support of the archrival Sooners from the University of Oklahoma), and the guy who delivered the paper every morning, as well as those of Allan’s patients lucky (or perhaps unlucky) enough to have a late December appointment with him. They made gingerbread persons (“I refuse to call them men,” Elaine told Lizzie. “After all, they could be women wearing pants”) as well as chocolate and peppermint thumbprints. Elaine had a large collection of cookie cutters, and they used these to make sugar cookies: bells, reindeer, wreaths, and plain old circles. They added small holes at the tops of one batch of assorted shapes so that later they could be hung on the tree.

“It’s easier to roll out cookies if you refrigerate the dough for an hour or so. A lot of people don’t know that, and they try to do it all right away. Not a good idea. And that gives you time to start straightening up the kitchen or, even better, to sit and have a cup of tea.”

When the cookies were cool, Lizzie helped decorate them. Lizzie had extensive past experience with frosting—she and Sheila used to spend many hours of their time together baking and frosting cookies and cakes. Perhaps applying frosting was a talent, like bicycling, that once learned is impossible to forget. And anyone can shake sparkles onto a cookie. You can be clumsy and ill at ease and still do a good enough job. Although maybe she was putting on too much? No, and so what if she were? She knew that Elaine wouldn’t care. She started to feel a little better.

Finally, Elaine made mandel bread, “the Jewish biscotti,” Elaine told her. “They’re Allan’s favorite, and George and Todd love them too. We’ll probably have to make more tomorrow or the next day. They’re pretty labor-intensive—you have to bake them twice, so we don’t have them very often. Have you ever had one?”

“No, I don’t think so. I mean, biscotti, yes, every coffee shop in Ann Arbor has them, but not mandel bread.”

“Ah, coffee shops,” Elaine said ruefully. “You’ll find that they’re few and far between in Tulsa. Not like Montreal, where there’s one on every corner. I think that sort of really urban lifestyle is what I miss most about living here.” Lizzie nodded but couldn’t decide if she needed to respond, or if she even had anything to add to the discussion.

“Two things to know about mandel bread, though, besides how delicious they are. They eat up”—and here she glanced at Lizzie meaningfully as if to say, “‘Eat’: Do you get it?” looking for all the world like George when he made a joke—“an inordinate amount of time. Plus, if it’s finger-licking-good cookie dough that you’re after, they’re not what you want to make. When I’m in a wanting-to-eat-lots-of-dough sort of mood, I make banana-oatmeal cookies. That dough is unbeatable. But once they’re baked, mandel bread is pretty irresistible. We’ll bake some extra so that I can send a couple of tins back to Michigan.”

Lizzie enjoyed playing sous-chef to Elaine, rummaging through the kitchen cupboards for whatever was needed for each recipe. They spent a companionable day together, mixing, tasting, rolling, baking, nibbling, washing up, and eating. Lizzie discovered that Elaine also dunked her cookies into her tea. The winter sun shone through the six-pointed mosaic star hanging in the window. It cut the light into straight-edged patches of color that landed on the table, the stove, and even Lizzie’s arm as she moved around the kitchen. By the time they finished drying the last of the baking sheets, measuring spoons and cups, cooling racks, and multiple spatulas, Lizzie, calmed down and almost happy, felt that all she wanted to do from this day on was to follow Elaine through the rest of her life. Suddenly she badly wanted to tell Elaine about the Great Game, about Jack, about how she didn’t really know how she felt about George, but she also knew that, for a number of reasons, both obvious and not, it most likely wasn’t the best thing to do.

“Do it, do it, do it. Ruin everything right now,” the voices in her head chorused. “Tell her all about it. Do it, do it, do it.” But Lizzie refused to listen to them.

Right after dinner, they all went together to choose a Christmas tree. Elaine, Allan told Lizzie, was always inclined to take the first really tall and bushy one she saw; it was how she shopped for everything: quickly and decisively. Allan insisted on walking through the entire lot before he’d finally reach a decision on what tree he wanted. Elaine pointed out to Lizzie that the tree they finally bought was exactly the one that she’d chosen in the first five minutes of arriving at the tree lot. Everyone laughed, including Allan. By the time they got home and George and Allan had the tree set up in the living room, there was just time for more cookies and hot chocolate before they all trooped upstairs to bed. Lizzie thought that this was close to a perfect day, certainly the best since Jack left.

December 23

The morning and most of the afternoon were devoted to decorating the tree. Lizzie expected Elaine to bring out boxes of ornaments—family heirlooms, perhaps—but learned that each year the Goldrosens made everything that went on the tree. Allan left for work, weighted down with many bags of cookies for the staff and patients, but George, Elaine, and Lizzie sat around the kitchen table—there was still a lovely tinge of cookie in the air—cutting Christmas wrapping paper into strips so they could put together chains to hang on the tree. Lizzie remembered making chains in elementary school using construction paper, which had been much harder to work with.

Elaine said, “You know, Lizzie, George will tell you that I’m terrible at arts-and-crafts projects. And he’s right. I don’t do this sort of thing at all the rest of the year. It’s just that I love all the ephemera of Christmas, and I’ve always liked the idea of having a do-it-yourself holiday, or at least as much as we can do ourselves.”

“She’s not kidding about her craft skills,” George added. “Her favorite book when we were growing up was Easy Halloween Costumes You Don’t Have to Sew.”

Elaine chuckled. “I always thought I should buy dozens of copies of it and give them out at baby showers. I am very adept at stapling, if I do say so myself.”

“You were the best, Mom. Too bad there wasn’t a stapling contest you could enter.”

“Did you and Todd help make decorations when you were little, George?”

“Oh, absolutely.” George started laughing. “One year, when Todd was seven and I was five, Mom left us alone when the doorbell rang—who was it, some delivery guy? Or was it a phone call?—and we had a paste fight while she was gone. We covered our hands with it and then chased each around the house trying to smear it on each other. There was paste absolutely everywhere—the walls, toys, our faces, clothes, beds, refrigerator. Mom was not happy with us. I remember that too.”

“It was a call from your grandmother, wondering what time we’d get to Stillwater the next day, and then she went on and on about the jewelry store and did I want this necklace that they’d special ordered for someone who never picked it up? I couldn’t get off the phone. I kept trying to tell her I had to go and she kept talking over me. I knew something was going on with you two boys. And all these years later, I sometimes still find dried blobs of paste around, stuck to something totally unexpected, like the bottom of the waffle iron. I guess it’s also a sign that I never clean thoroughly enough either.”

“And even after that, Mom was so desperate for help that she put up with us.”

“It’s more that it’s no fun doing this alone. The fun is being together, like we are now.” Later they strung popcorn and cranberries into more chains to loop around the tree and on the mantel. George was quite deft at this part of the work. (It was why he would go on to be such a good dentist: patience and skill.) Lizzie could imagine him and Todd poking at each other with their needles, with much popcorn being eaten and/or spilled, and fresh cranberries rolling across the kitchen floor, waiting to be squashed by sock-clad feet.

On that first visit, when all the chain making and stringing was done, George took Lizzie on a short tour of his past. The bowling alley in West Tulsa, he said, which was ultimately the reason they were together, here, now, at this very moment, went out of business long ago, but they drove to the strip mall where it used to be. “Look—I think that’s the same gaming store where Todd used to skip out on bowling to play Dungeons and Dragons,” he said. “Who’d have thought that it’d still be around?” His high school was closed for vacation, so they couldn’t go in, but Lizzie couldn’t help comparing the spaciousness of the large campus—with its lower, middle, and upper schools spread out over several acres of well-manicured lawn—to the cramped, creaky, and much older building where she’d spent her high school years. They went for a walk along the Arkansas River. It didn’t, Lizzie told George somewhat belligerently, even compare with the Huron. George readily agreed.

“But it’s pretty neat that we both grew up with rivers in our lives, isn’t it?”

All this “we”-ness with George was making Lizzie uncomfortable. She tried to find a neutral subject.

“Your mother’s great.”

“Yes,” George answered immediately, “she is. She thinks you’re pretty wonderful too,” he added.

The voices in Lizzie’s head jumped in quickly, as though they’d been waiting for just this opportunity: “And here I thought George’s mother was a lot smarter than that. If she really knew this kid she wouldn’t like her at all.”

“Really?” Lizzie said, obscurely pleased but wondering if the voices didn’t know better than George. “She doesn’t really know me.”

“C’mon, Lizzie. I know you and I think you’re entirely wonderful. Really.”

Oh, George, Lizzie said to herself. You don’t know me at all. If you did, you would never use the adjective “wonderful” to describe me.

That night they went to see Back to the Future and then out for pizza and beer with Blake, who was George’s best friend ever since they were kids, and Alicia, his fiancée. They were both teachers—Alicia in elementary school (kindergarten) and Blake in high school (history and football coach)—and they spent the entire evening talking about Blake and Alicia’s upcoming wedding, save for the two hours and six minutes that the four of them watched the movie. Everyone except Lizzie had already seen it (Blake and Alicia twice before), but they agreed that it was worth watching any number of times. Lizzie thought perhaps once was enough for her. Afterward, they drifted into a bar around the corner.

While they drank their second pitcher of beer, Blake and Alicia took turns telling Lizzie and George in almost minute-by-minute detail how they had arrived at a wedding date (in Lizzie’s view a particularly pointless account that ended with the decision being made via a flip of a coin) and had chosen a caterer—lots of taste testing, which was great (Blake), and too fattening (Alicia). They shared the pros and cons of getting married in a church and having the reception there rather than at, say, a hotel. Alicia took out Polaroids of her four bridesmaids trying on their dresses. “We found them at Miss Jackson’s and thank goodness everyone’s pretty much a standard size, because I don’t know what we’d have done otherwise. It’s almost impossible to find a dress and a color that looks good on everyone, don’t you think, Lizzie?”

“Sure. Absolutely,” she automatically responded. Do I care, Lizzie wondered, if Alicia and Blake like me? What are the chances that I’ll never see them again, which would be just fine with me? Does George care if I like them? I hope not but I just bet he does.

In light of that belief, Lizzie opted not to point out to Alicia that she and her bridesmaids were all blond and about size six, so how hard, honestly, could finding the right color be? Instead she tried, for George’s sake, to look interested.

“Oh,” Alicia said suddenly to Lizzie, who was now peering intently into her beer, hoping it would reveal a future that included Jack. “Did George tell you that he’s the best man? And, Lizzie, you should totally come too. It’ll be so much fun.”

“Best party of the year, Lizzie,” Blake promised. “And you’ll get to meet all George’s friends at one go.”

“I’ll see,” she told them. “I’m not really sure where I’ll be in June. I might be traveling.”

George looked at her quizzically but didn’t say anything, which was good, because the voices were having a field day attacking her. “Traveling. I might be traveling,” one mimicked her. “Couldn’t she even come up with a better excuse? Please tell me where on earth she could be traveling.”

“Just tell them the truth,” the other voice advised. “Make it clear how stupid you think they are.” Lizzie tried not to listen, but it was hard.

“We’ll get your address from George,” Alicia called out as George and Lizzie walked to their car. “For the invitation. But we’re counting on you being there.”

“Aren’t they a great couple?” George asked cheerfully as he opened the car door. He was looking forward to parking somewhere and fooling around with Lizzie in the backseat of Allan’s big Buick. “You liked them, right?”

Lizzie’s fallback position was almost always to lie, and she tried out a few different sentences she could use with George. “What the hell,” she said to herself, and spoke. “Truthfully, George, I found them pretty boring. If you must know, I’d rather have stayed home and talked to your mother. Tell me again why we had to go out with them tonight?”

“Mom’s great, so I get that, but Blake’s my best friend,” George protested. “I always see him when I come home.”

“Too bad,” Lizzie said, the voices in her head going wild. “Was he always so uninteresting?”

“Uninteresting? Are you kidding?”

I’m pretty sure that lying would have been the smarter thing to do, thought Lizzie. But it’s too late now. “No, I’m not kidding. As I’m positive Alicia and her blond friends would put it, I think they’re BORR-innnggg.”

“That’s not how she’d describe herself and Blake.”

“Oh, George, you know what I mean. That’s definitely how she’d say the word ‘boring.’ That’s b-o-r-i-n-g, in case you’re wondering how to spell it. BORR-innnggg.”

“Lizzie—”

“No, wait, George, listen, what did we talk about all night? Their wedding.”

“What did you want to talk about that we didn’t?”

“Anything. Politics, science fiction, the Super Bowl, China. The breakup of the Soviet Union. Poetry. Whether Britain should abolish the monarchy. The future of Africa. Whether pot should be legalized. The price of eggs.”

“Is that what you and Marla and James talk about? How much eggs cost these days?”

Against her will, Lizzie laughed. “Well, not about legalizing pot, at least not when James is there, because legalization would ruin his business. But do you see what I mean? I think hearing about someone else’s wedding is the definition of tedium. And she’s so blond.”

The first of Lizzie and George’s many many Difficult Conversations might have ended there and the evening salvaged, except that Lizzie refused to let it drop.

“They just went on and on about the color of the bridesmaids’ dresses and cake tastings. Do they even read?”

“Lizzie, Blake has a master’s degree in history. And he’s not stupid. I mean, he’s not going to win the Nobel Prize for Physics, but, hey, are you? He was captain of our Lincoln-Douglas debate team in high school. And I bet he’s a good enough history teacher. I know he’s a great football coach. The team worships him. I don’t know Alicia very well yet, but I do know lots of the girls that Blake dated before he met her, and they weren’t stupid either. Oh, yeah, and he graduated magna cum laude. That’s more than I did.”

“Sure, from some third-rate A-and-M college.”

This was more than even George could take. “Hey,” he said, sadly coming to the conclusion that his deep desire for a make-out session ending with sex with Lizzie was not going to be fulfilled. “I went to that third-rate school too, you know. And it’s a university. It stopped being Oklahoma A and M years ago. In the 1950s. And my dad went there. And he’s no dummy.”

“But you eventually left,” Lizzie pointed out.

“After I graduated. Because it doesn’t have a dental school.”

“And Todd didn’t go there.”

“He didn’t go anywhere. He was in Sydney.”

Lizzie realized the particular thrust of that argument had run its course, and she shifted topics. “So tell me, where’d little Miss Perky go, again? I know you told me, but I forgot.”

“Oral Roberts University,” George said stolidly. He’d known that was coming.

Lizzie sniggered evilly. “I read about that college. You know, don’t you, that they have spirit monitors on every floor in the dorms, so that someone can tattle to someone else if you’re breaking a rule or even edging close to it. I bet your precious Alicia was a spirit monitor. Maybe she can give you some spiritual guidance. Besides, neither of them asked anything about me, like what I was studying, or how we met.”

“Blake knows how we met. I told him and I’m sure he told Alicia.” George paused awhile before going on. When Lizzie started to speak he stopped her.

“Listen, Lizzie, I don’t know how we got into this . . . well, I do know how we got into this, but I just want to say something, and maybe this is an awful time to say it, and maybe I shouldn’t, but listen, Lizzie, do you even care about what’s going on in my life when we’re not together, or what my life was like before we met? You don’t ever ask. Do you ever tell me anything important about your own life? No. You never share anything. I’m amazed you invited me to Thanksgiving dinner. You’re probably one of the most self-centered people I’ve ever met. And, oh, yeah, I’m pretty sure that I’m in love with you, although I can’t imagine why.”

He started the car, ignoring the tears that were now rolling down Lizzie’s cheeks. Neither spoke until they arrived back at Allan and Elaine’s. Lizzie, still crying, started to open the car door, but stopped when George put his hand on her arm.

“You’re a real snob, Lizzie Bultmann, did you know that? It’s their big day, and I’m going to be the best man. Why shouldn’t they talk about it to me and expect me to be interested?”

“Well, were you?”

“No, not particularly,” George admitted. “It did get boring, I agree. But if it were our wedding, I’d expect Blake to let us talk about it too.”

Lizzie groaned. “But cake tastings and bridesmaids?”

“Even that. It’s what friends do.”

“But they’re not my friends.”

“Not yet, no.”

“Not ever.”

It was George’s turn to groan, which he did, loudly. “Look, you’ve just met them once. Can’t you cut them some slack? Surprise, surprise, they might grow on you.”

She sniffed. “I’m not too enthusiastic about slack.”

“Then you have a difficult road ahead of you.”

“I guess. But that’s so not-new news to me.”

Finally he turned to look at her. “I don’t want us to fight; I really want you to have a good time here. We don’t have to agree on everything. I love you, I just wanted you to know that.”

Lizzie shook her head, but didn’t say anything, whether from sadness, or pity, or frustration, George couldn’t tell.

December 24

When Lizzie came downstairs the next morning, Elaine was sitting at the kitchen table with a mug of tea and the newspaper. Lizzie poured herself some tea from the pot and sat down with her.

“George went to pick up some stuff for his grandparents. He should be home soon, but I’m glad we have this time to ourselves. I wanted to tell you something.”

Lizzie put down the cup, but not before the tea sloshed on the table. How had she so quickly come to this point of being afraid that Elaine might have realized that she was just pretending to be the nice girl that her son was dating? Oh, right, that her son was in love with. With whom her son was in love.

Elaine got a sponge and wiped up the spill, not noticing, or deliberately overlooking, Lizzie’s discomfort. “I wanted to tell you, so you’re not surprised when you meet her, that my mother-in-law can be a real terror. She loved—still loves, of course—Allan, to the point of distraction, and Todd and George even more than that. She worships them. It was lovely when the boys were growing up because she’d always be so happy to listen to my stories about them over and over. She’s always been forthright, but now I think she’s deliberately modeled herself on Maggie Smith, the British actress. If there’s a tart remark to be made, Gertie will undoubtedly make it.

“It took her a long time to warm up to me. She was furious that Allan wanted to marry me and terrified we’d live in Canada near my folks rather than in Oklahoma. Over the years we’ve become closer, but I wanted to warn you about how difficult she can be. On the other hand, Sam is uncomplicated and totally likable. Allan’s just like him, and you know how nice he is. There. That’s done. I haven’t offered you breakfast because you’ll stop at the Pancake House in Sand Springs, which is yet another of the Goldrosen traditions you’ll get to experience.”

“You’re not coming with us?” asked Lizzie, a bit dismayed.

“We’ll see them next week, after the Christmas tree comes down.”

“I wish you were going to be there,” Lizzie allowed herself to say.

“No, no, you and George will have a nice day by yourselves with Gertie and Sam. And one more piece of advice: Don’t eat a lot at the Pancake House, because Gertie will have cooked up a storm in anticipation of your visit. And unlike me she’s an excellent cook. Plus, and most importantly, her feelings will be hurt if you turn down her offers of second and third helpings.”

George heard the last sentence as he came in the door. “Just wait, Lizzie. Grandma’s company meals are amazing. You won’t be able to see the table because there’ll be so many dishes on it.”

They stopped at the Pancake House in Sand Springs and then drove through Mannford, along the edge of Oilton, and from one side of Yale to the other before they finally got to the outskirts of Stillwater. Neither brought up what had happened the evening before. George told Lizzie about his grandparents; she didn’t mention what his mother had said, although Elaine hadn’t indicated that it was a secret.

“After they realized that neither their son or either of their grandsons would ever want to move back to Stillwater and manage Goldrosen’s Fine Jewelry, Gertie and Sam decided to sell the store to one of their employees,” George began. “The guy who bought it immediately changed the name to Bling It On. There’s no way that Sam and Gertie would get the joke, and they were terribly distressed that he felt he needed to rename a business that had been successful for a long time.

“Even the decision to sell the store had been very hard, because my great-grandpa began it almost seventy-five years ago. Family history says that his boat docked in Houston and he walked all the way to Tulsa with a peddler’s cart that he picked up somewhere. He didn’t speak much English and didn’t have any relatives here because the older brother who’d sponsored him unceremoniously died before the boat even made it to Houston. Sam told me that his father once described the long slog from the Gulf of Mexico to Stillwater as moving from the wet heat to the not-quite-so-wet heat. Once he got to Stillwater it felt like he was home for good. And that’s how Gertie and Sam feel. They still live in the house that my dad grew up in. And,” George concluded, “Goldrosen tradition mandates that the grandsons, if they happen to be in Oklahoma, celebrate Gertie’s December twenty-fourth birthday in Stillwater. That’s partly why I come home every Christmas.”

“So why aren’t your folks coming with us? Or why don’t your grandparents come to Tulsa to celebrate?”

“Well, Grandma absolutely refuses to set foot in our house as long as Mom has all the Christmas stuff up. And Pop, which is what we’ve always called my grandfather, goes along with her. You’ll see, she’s the one in charge.”

They drove some more. Lizzie looked out the window at mostly different shades of brown, in a mostly unchanging landscape. She couldn’t understand why anyone would want to live here. “How come you decided to go to OSU for college? Didn’t you want to go further away from home?”

He turned the question back at her. “How come you decided to stay in Ann Arbor and go to college there? Didn’t you want to get further away from home?”

“That was different.” Even to herself Lizzie sounded defensive.

George asked the obvious follow-up question. “Different how?”

If diversion were an Olympic sport, Lizzie would most definitely medal.

“But obviously Todd left Oklahoma, so people do leave.”

George, then and nearly always, was willing to indulge Lizzie, and didn’t pursue his own question. “Yeah, Todd went about as far away as he could, but I knew that I’d probably go out of state for graduate school, so it seemed silly to leave before I really had to. Besides, from the time I was a little boy, we had season tickets for all the Cowboys’ basketball and football games. I loved coming to Stillwater to watch the games with my dad and Pop. It wasn’t ever a big deal to Todd, but I hated to think about the two of them going to the games alone, without me. It would have broken their hearts if I left too, just a few years after Todd did. I still feel guilty that I’m in Ann Arbor and not here on football Saturdays.”

“What did your mom want you to do?”

“Oh, I think she really wanted me to go east to school. It’s an understatement to say that she’s never loved Tulsa. A few years ago she told me that she still spends her days kicking and screaming against the circumstance of living here. When Dad proposed to her she made him promise that they’d never move back to Oklahoma.”

“What’d he say to that?” Lizzie asked, fascinated.

“That it was only sons whose fathers owned oil companies who come home to Oklahoma to run the family business, that he wasn’t interested in living in Stillwater and working in the jewelry store. He basically promised that it wouldn’t ever happen. And then he added something about orthodontists pretty much having the whole country to choose from.”

“What’d she say then?”

“That, yes, she’d marry him.”

Lizzie thought for a few minutes. “So what happened when your dad decided to come back?”

“He didn’t tell her until he’d almost finished his residency, so they’d been married a few years by then. I think they argued a lot and for a long time. Mom never talks about that part. But Dad tried to convince her that, because they weren’t moving to Stillwater, he wasn’t exactly breaking his promise to her. She hates that kind of quibbling, so that made it even worse.

“When Mom’s telling the story, she says that she just decided to be a grown-up and a good sport about it and come here because she loved him and because she saw how important it was to Dad. But Dad says that she wept and raged and told him she was pregnant and didn’t want to be a single mother and that since he made the decision about where they’d live and bring up their kids, she could decide everything else from then on until they died.”

Lizzie was becoming by the moment ever more infatuated with Elaine.

“Gosh, has she? Made all the other decisions? Or was it just an idle threat?”

“They agree about most things. I don’t think Dad has ever been thrilled about all this Christmas stuff, but he goes along with it, even if he knows it upsets his parents.”

George changed the subject. “Did either of your grandparents live near you when you were a kid?”

“Oh, George.” Lizzie sighed. “You met Mendel, and Lydia’s even worse, if that’s possible to imagine. You know they’re automatons, constructed out of coat hangers, powdered milk cartons, and a heart cut from a piece of graph paper. Nobody could possibly have given birth to them. I don’t have grandparents.”

George sighed. What could he say?

Gertie and Sam were sitting on the front porch, waiting for them. George enveloped his grandmother in his arms, loudly kissed her cheek, and told her happy birthday, then shook his grandfather’s hand and pulled him in for a hug too. Only then did he put an arm around Lizzie and introduce her to his grandparents.

“This is Lizzie,” he said proudly.

“It’s so nice to meet you both.”

The elder Goldrosens gave Lizzie identical tight smiles. They’d met several of George’s girlfriends in the past and didn’t have high hopes for this one either.

“Can we go inside?” Sam asked plaintively. “I’m freezing. And starving.”

Lizzie handed Gertie the bouquet of flowers they’d bought that morning on their way out of Tulsa. “Happy birthday,” she said.

“Whose idea was it to buy me flowers?” Gertie asked sharply. “Georgie? Why would you waste your money?”

“But they smell beautiful,” Lizzie protested. Gertie gave her a look of such scorn that it brought back vivid memories of Terrell the Terrible and that awful poetry class where she’d met Jack. Jack. What was he doing this very moment? Did he ever think about her? Why had he really left her? Where was he? Not in Stillwater, Oklahoma, for sure. But why couldn’t he be here? Lizzie decided that she needed to find a phone book to check if against all the odds he was now in the exact same (small) city that she herself was.

That progression of questions she’d directed at herself sidetracked Lizzie enough that she almost missed Gertie saying dismissively, “None of the flowers you buy from florists ever smell as good as the ones you pick yourself. These probably began the day in some New York hothouse. Ha! You know, Georgie, come spring, my wisteria perfumes the whole house.”

“It does indeed, Grandma,” George said, winking at Lizzie.

“Of course, the downside of that smell is that the wisteria is threatening to take over the whole backyard, not to mention the house, but Gertie can’t bear to cut it down,” Sam said. “If she ever decides that she wants to get rid of it, George, you and Allan will have to come dig it out. Those roots are more aggressive than telemarketers. We might have to bring Todd back from Australia to help us.”

“Well, I suppose it was sweet of you to bring me these, Lizzie, although I’d have thought that Georgie might have mentioned my feelings to you, but no matter. The damage is done.”

George was laughing as they walked into the living room. “Grandma, I had no idea you felt so strongly about florists and flowers. We’ll do better next time. Here, sit down and open the rest of your presents. Here’s a little something from Mom.”

“Is it my mandel bread?” she asked eagerly as she opened the cookie tin. It was. She bit off a corner of one. “Not bad. I do have to give Elaine some credit: for a terrible cook she makes the best mandel bread I’ve ever tasted. Even better than mine. Perfect for dunking.”

“And you’ve dunked plenty of them in your lifetime, Grandma, right?”

“She’d get a blue ribbon at the fair if they had a dunking-and-eating-mandel-bread category,” Sam said proudly. “That’s my wife.”

George gave her the last package. It was smallish and rather lumpy, wrapped in paper with “Happy Birthday” written on it in different languages.

“Oh,” Gertie said delightedly as she opened it. “What a surprise. Socks.” She turned to Lizzie. “Every year since he was six I’ve gotten a pair of socks from Georgie for my birthday.”

This particular year’s were blue, with a blotch of maize at the toes and heels and a tasteful maize M at the top.

“Thank you, Georgie. These are very nice, but a little tame for my taste, don’t you think? Not like those orange knee socks with Pistol Petes all over them that you once gave me.”

“Pistol Pete is OSU’s mascot,” George explained in an aside to Lizzie.

“I loved those socks. I wore them till they disintegrated in the wash. I wish you’d find me another pair,” Gertie said wistfully.

“What can I say, Grandma? This was pretty much all I could find in Ann Arbor, except for some plain white ones, which I knew you’d hate. And I thought you’d like the colors.”

“I do, I do. You’re such a sweet boy, Georgie.” By stepping back, George successfully deflected her attempt to pinch his cheeks.

“Come on,” Sam urged them. “Let’s eat lunch. Are you kids hungry? I feel like I might faint from hunger.”

While his grandparents were getting the food on the table, George showed Lizzie the framed class photos of him and Todd, beginning in kindergarten and ending with George’s photo from his senior year in high school. “You were a pretty cute kid,” Lizzie said. “Did you break a lot of hearts?”

George started to answer but was interrupted by Sam’s insistence that they sit down at the table now, this minute, before the food got cold. Lizzie imagined that George might have said that he was constitutionally unable to break anyone’s heart. Or he would have said something about not if you compared him to Todd. Yes, she already knew those things about him.

“Soup’s on,” Sam called again.

Literally, in fact: on their plates was a bowl of chicken soup with matzoh balls. That was followed by sweet-and-sour braised brisket. There were also latkes with a choice of applesauce or sour cream (or both), and kasha knishes. There were both meat and cheese blintzes. There was a loaf of challah still warm from the oven. Lizzie didn’t think she had ever seen a table so crowded with food.

“Good Lord, Gertie, how much of this do you think we’ll eat?”

“Stop, Sam. I wanted George to have a taste of Hanukkah. I know he doesn’t get this kind of food from his mother. And save room for dessert,” Gertie warned them. “I want to get rid of the birthday cake Sam got me from Safeway. Chocolate. Waste of money, of course. It won’t be good. Those store-bought cakes become stale the minute you get them home. It’s just like how new cars lose most of their value as soon as you drive them off the lot. So I made some of your old favorites, Georgie, just in case it’s really inedible. And don’t anyone spill their coffee. It’s impossible to get those stains out of the tablecloth.”

Of course the cake was absolutely fine, but Gertie didn’t care for it. The chocolate frosting was too sweet. She thought they’d used inferior ingredients. To clear their palates of the bad taste, she insisted that they each take a generously sized brownie and several miniature cream puffs filled with vanilla pudding and drizzled with chocolate sauce. No one wanted ice cream, although she offered to get it from the freezer. Twice.

By the time Lizzie finished eating everything Gertie had insisted on serving her, all she wanted to do was crawl into bed and sleep. It’s possible she dozed off for a moment. Gertie and Sam were carrying platters of food back into the kitchen, and George was clearing the table. With some difficulty, Lizzie rose to her feet and made a move to help, but Gertie said, “No. Just sit. You can help another time.”

“Are you sure, Mrs. Goldrosen?”

“Absolutely sure. I’m very particular about how I load the dishwasher. Don’t you find everyone is? I’m sure your mother has her own thoughts on the subject.”

Lizzie, not being sure whose mother was being referred to, didn’t answer. As far as she could remember, Lydia hadn’t ever expressed an interest in, or opinion about, their dishwasher. She’d certainly never put a single dish in it. Come to think of it, she might not even know the Bultmann family owned one.

Later, they showed Lizzie the sights of Stillwater. George drove and his grandparents narrated the journey. They pointed out George’s freshman dorm, the fraternity where he lived for the next three years, the football stadium, the basketball arena, the first McDonald’s (“We watched it being built, early in the 1970s”), Baskin-Robbins (“Ditto”), the house where Allan’s best friend used to live when they were kids and the house where he and his family lived now (“He came home, you know, to teach at the vet school. I don’t know why your father didn’t bring your mother here. We needed an orthodontist more than Tulsa did.”), Allan’s dorm, Allan’s fraternity (the same as George’s) and his elementary, middle, and high schools (“He was president of his junior and senior classes, you know, George.”). George slowed down in front of Bling It On, but Gertie told him not to stop. “Let’s just go home, George. I’m getting tired.”

When they got back to the house, Gertie announced that it was time for a little something to nibble on before George and Lizzie left. Rather than the brownies and cream puffs (the chocolate cake had been discarded), she brought out a banana cream pie (“I made Allan’s favorite, even though he’s not here”) and an angel food cake, with strawberries and whipped cream (“Sam’s favorite; I froze the strawberries myself.”). “And it’s real whipped cream, not that stuff Elaine serves,” she announced.

While George and Lizzie were getting ready to go, Gertie disappeared into the kitchen and returned with Tupperware containers full of food to take back to Tulsa. “I kept the brisket,” she apologized, “because Sam will want more meat blintzes. But I packed up everything else. It’s a care package for Allan, like I used to send you boys when you went to camp. I know Allan misses my cooking, even though he probably never complains.

“And here’re your Hanukkah presents. Open them now,” she commanded. George waited while Lizzie unwrapped hers, trying to be as careful as Gertie had been with the gift from George. They’d given her a box of assorted Twining’s teas.

“Oh, thank you,” she said sincerely. “I can’t wait to try all the different flavors.”

Gertie nodded. “George told us you were a tea drinker. Like Elaine.” Lizzie wasn’t quite sure how to take this statement. Being like Elaine in this house was evidently a mixed blessing.

George’s package was lumpy, a much larger version of the wrapped pair of socks he’d given to his grandmother earlier. He examined the wrapping paper. “This looks familiar,” he commented, and asked her if it was same paper she’d used on his gift last year. He took the absence of any response as a somewhat guilty yes. “Well, then,” he said breezily, “there’s no need to save it for another year,” and tore it open.

“Oh my gosh. You guys shouldn’t have. Look, Lizzie.” This last was unnecessary, since where else would Lizzie be looking but at George’s gift? It was a hooded orange sweatshirt emblazoned with a large Pistol Pete outlined in black on the front and cowboys written on the back. “Wow. I’ll be especially sure not to wear this on game days in Ann Arbor; it isn’t safe to acknowledge there are any other college teams. But here I can wear it all the time.” He put it on over his flannel shirt.

Gertie and Sam looked pleased. “Wear it in good health, sweetheart,” Gertie said. “You’d better get going. We don’t like to think of you driving home in the dark.”

They all stood around the car saying their last good-byes. Lizzie went back into the house, ostensibly to use the bathroom, but really to check the phone book in the kitchen. She opened it to the M’s. She could never remember if the Mc’s came before or after the Mac’s or if they were just in their normal place in the alphabet, but after looking carefully she saw there was no Jack McConaghey. No Jack. She’d been right. He’d never live in Stillwater, Oklahoma.

Sam hugged them both, and Gertie kissed Lizzie and then threw her arms around George. “You’re always the best part of my birthday every year, Georgie,” she told him. “You and Todd.”

As George backed the car out of the driveway Lizzie turned around and saw Gertie standing on the sidewalk, waving to them. “She’s crying,” she said to George.

“I know, I know, I hate it, but she always does when we leave.” He sighed. “I should really try to come here more often.”

“What are you going to do with that hideous sweatshirt? ‘Oh my gosh. You shouldn’t have,’” she imitated him.

“Hey, I was being honest. They absolutely shouldn’t have.”

They laughed together.

“It was probably on sale,” George said.

“Oh, for sure,” Lizzie agreed. “Otherwise why would you ever buy it, even given your deep love for Pistol Pete? That’s got to be the brightest orange I ever hope to see. It’ll give most people a headache.”

“Or blind them. Maybe it’s like looking directly at an eclipse of the sun. How about if I leave it at home and only wear it when I’m visiting them in Stillwater? That’ll satisfy everyone.”

“But they’re sweet,” she continued. “At least Sam is sweet. I’m not sure how to describe Gertie. I wish I knew my grandparents. Maybe my life would have been totally different.”

“Not so totally, I hope. I’d still like us to have met.”

Why did George have to say things like that? What did he want her to say? That she felt the same way? They still hadn’t talked about what had occurred the night before. Maybe George would forget that he said he loved her.

She spoke quickly. “And all that food. I don’t think I’ve ever eaten so much. I can’t believe she did all that cooking.”

“Cooking for us makes Grandma happy. The thought of anyone she loves going hungry is anathema to her.”

“Your mother’s sort of the same way, isn’t she?”

“She is, but not to that extent. I think if we hadn’t eaten the cream puffs Grandma would have been really annoyed with us.”

“I wish I hadn’t eaten them,” Lizzie admitted. “I’ve probably gained ten pounds on this visit.”

George reached over and took her hand. “You don’t have to worry,” he said.

Just before they got back to Elaine and Allan’s, Lizzie said a little timidly, “Do you want to talk about last night, George?”

“No, not right now. We can wait at least until all that food’s been digested.”

“I just thought,” Lizzie began, “because I just want to say I’m sorry I was such a pill about Blake and Alicia. It was probably uncalled-for. For some reason I was really uncomfortable with them.”

George nodded. “Okay, that’s fair. Though I did wonder about where you might be traveling in June, since you never mentioned it before.”

“Right,” Lizzie said, trying to pretend she hadn’t said anything of the kind. “I did say traveling, didn’t I. Maybe I meant to Marla’s, I don’t know. It’s all I could think of at the time.”

“Hold that thought, Lizzie. We’re home.”

December 25

After breakfast on Christmas day, the Goldrosens gathered around the tree to open presents. It was almost as though Lizzie had always been part of the family. There was even a stocking with her name on it, hung on the mantel next to the other three. Elaine saw her looking at it and misread her thoughts, one of the rare blunders Elaine would ever make in understanding Lizzie. Which was pretty amazing, given that she’d never learn what Lizzie considered to be the defining events of her life.

“I’m so sorry your stocking’s not like the rest of ours. By the time George told us you were coming, it was too late to order one. But we’ll have one here for you next year. And maybe Todd will be here too,” she said, a bit wistfully.

Once again Lizzie wasn’t sure what to say, although she was pretty sure she should say something. George fidgeted and didn’t look at either his mother or Lizzie. Oh God, Lizzie thought. What the fuck is going on? First George says he loves me and now this. If I were living in a horror novel, that would be the first vaguely ominous sign that I’ll never get untethered from this family. Maybe Elaine can predict the future. Or maybe she’s just insanely optimistic.

George felt, for what was perhaps the first time in his entire life, a tinge of annoyance at his mother. It was one thing for Alicia to invite Lizzie to the wedding and quite another for his mother to blithely assume—blithely assume!—that she’d be here next Christmas and forever after, even if that was exactly what George wanted.

They opened their gifts in turn, accompanied by a significant amount of oohing and aahing. Lizzie’s presents were unexpectedly many and lavish: a very pale green bathrobe made out of the softest cotton she’d ever felt, sheepskin slippers, a rather large gift certificate to Shaman Drum bookstore, several bars of French milled soap (Marla would approve of that, Lizzie thought), an alarm clock from the Museum of Modern Art, and two mismatched china teacups and saucers.

George’s presents included a cashmere scarf, a pair of sheepskin slippers, a bottle of Italian wine, four Riedel wineglasses, a lamb’s-wool sweater, and a mug inscribed my favorite dentist.

Todd had sent his father a silk tie, his mother a boxed set of Upstairs, Downstairs, George a furry hat with earflaps, just like the kind they used to wear as kids, and Lizzie a pair of suede gloves.

“Oh,” Lizzie said, stricken with guilt. “I didn’t get Todd anything.”

“I did,” George assured her. “A Dallas Cowboys warm-up jacket. That should confound the Aussies when he wears it.”

Elaine and Allan were beaming. It finally occurred to Lizzie to wonder if George had ever brought another girl home for Christmas with his family, and, if so, what happened to her. Could it have been the girl he was with the night they met? What was her name? Lizzie thought she might ask George about it on the plane ride home.

George surveyed the stacks of gifts he and Lizzie had gotten. “We’ll need another suitcase to carry all this back to Ann Arbor, Mom.”

“Easily solved. You can take one of ours and just bring it back next time.”

Allan looked at his watch. “We’d better get over to the shelter. They’ll be serving lunch soon. Who’s going with me? George? Elaine? Lizzie?”

Elaine spoke first. “I’ve got lots and lots of cookies and a couple of casseroles for you to take, but perhaps Lizzie and I will stay home. Is that okay with you, Lizzie, or do you especially want to go?”

“No, staying here is fine. We can eat cookies and try some of the teas from Mr. and Mrs. Goldrosen in my new teacups.”

“Lovely,” Elaine said, “and listen, I’m sure they’d be happy to have you call them Gertie and Sam.”

“Of course they would,” Allan added.

Sam, maybe, Lizzie thought. Not Gertie.

“I’m devoted to mismatched china,” Elaine said as they were sitting at the kitchen table, drinking their tea—Elaine, Earl Grey, and Lizzie, Assam. “It just seems more festive to me. I don’t mean to inflict my taste on you, though. It’s too late to return these, now that we’ve drunk from them, but if you’d rather have two sets that match, I’ll keep these and send you some others.”

“No, no,” Lizzie assured her. “I just never thought about it before. They’re lovely.”

They sat in companionable silence while they sipped their tea.

“So, Lizzie,” Elaine began. “George told us your parents are important psychology professors at U of M?”

“Um, yeah, I guess so. A lot of people think they’re important, anyway.”

“I was a French major as an undergraduate, but I once considered going into psychology. I always thought I might be a good social worker or school counselor.”

“I bet you’d be wonderful at that. Do you ever think about going back to school to get a degree?”

“Oh, I’m not sure I even want to at this point. I think I’d rather be lazy and eat cookies and drink tea. What area of psychology are your parents in?”

“They’re behaviorists, so they don’t do counseling or therapy.”

“What are they like? Are you close to them? Were they okay with you spending the holidays here?”

Lizzie paused. How to explain? How much should she tell Elaine? (“You’re probably one of the most self-centered people I’ve ever met,” George had said.)

“I’m so sorry,” Elaine said instantly. “Is that too personal? You don’t need to answer. I’m just always curious about people’s lives.”

“No, it’s okay. I just need to figure out how to explain them to you. It’s like”—she fumbled with her words—“they’re just not the sort of people anyone could be close to.”

“That must be sad for you. And difficult.”

“Not really. Not anymore. It was harder when I was a kid. See, not only would they never do counseling, but they think psychologists who do do that are a joke. Or they would think it’s a joke if either one of them had a sense of humor. Psychologists like them, behaviorists, don’t believe in an ‘inner self.’ There’s actually a famous joke, or at least famous in behaviorist circles and of course those who dislike behaviorists, that goes like this: Two behaviorists meet on the street and each one asks the other, ‘How am I?’”

Elaine smiled. Lizzie wondered if she should go on. “Is this more than you want to know?”

“No, no, don’t stop. I’m fascinated. Do they really not believe in an inner self?”

“Well, at least they don’t believe that the notion of an inner self—or inner life—is useful for what they call the science of psychology.” Lizzie emphasized the last three words and added air quotes around them. “And it’s really important for my parents to think of themselves as real scientists.” More air quotes. “Just like physicists, or biologists.”

“How curious,” Elaine said as she stood up. “Let’s make another pot of tea—I want to hear more.”

While the water was boiling Lizzie said, “I think George is terrifically lucky to have you and Allan as parents. It’s just so nice here.”

Being in Tulsa at his parents’ house with George made Lizzie anxious (how did she feel about him, anyway?), but spending time alone with Elaine was calming and comforting and gave her some idea of what her life might have been like if someone besides Lydia had been her mother.

Elaine gave her a quick hug and then said, “You’re sweet. I see why George likes you so much. Okay, finish what you were saying before. I feel as though I should be taking notes. Are you going to give me an exam at the end?”

“Of course,” Lizzie said. “And I should warn you that I’m a very hard grader. Anyway,” she went on, “all those early behaviorists saw that real scientists, like biologists, only studied things that they could see, and you couldn’t ever see the mind. Except perhaps your own. And that might be enough to write poetry, but it wouldn’t pass muster as a scientific study. They believed that all that you could see was behavior. So they gave up any examination of the mind or the inner self, and just studied how people behaved. And if people insisted on talking about their ‘inner experience,’ well, that was just considered verbal behavior. Kind of embarrassingly bad behavior, in fact. Problem solved.

“I think it’s all bullshit,” Lizzie went on, “what my parents and their friends believe, and not just because they’re my parents and I’m rebelling against them. Everyone knows they have a mind. And I’d hate a life without poetry in it.”

Elaine nodded, a clear encouragement to continue.

“My parents think that people are like animals, and they’ll do what they’re rewarded for and won’t do what they’re punished for doing. And they think that’s a great insight.”

“Maybe some behaviorists should become animal trainers,” Elaine joked.

“Actually, a lot of them did go on to become pretty good animal trainers. And people trainers too. My father spends his days running lab rats to try to shape their behavior in particular ways. And because of that, he’s discovered some pretty effective ways of controlling people’s behavior too.”

“I’ve read about behavior modification. It’s all the rage in pop psychology books these days, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, but Mendel and Lydia usually publish only in academic journals that only their friends read. They’re not at all interested in dumbing down their theories for a mass audience.” Lizzie had a sudden flashback to the terrible afternoon that Jack showed her the article in Psychology Today. That hadn’t dumbed down anything at all. “They used to try their theories out on me, though, all the time. Once, when I was almost three, and my father was training rats to press bars in their cages in order to get food, they decided to see if they could train me to stand up whenever they entered the room, so if I was sitting down and reading or playing with a toy when they came in, they’d be all cold and ignore me, but the minute I got up they started paying attention to me and acting loving. And sure enough, just like a rat, I learned what to do. It was like turning the handle on a jack-in-the-box. As soon as either one of them came into the room I, I’d pop right up. Things like that went on all the time. It didn’t end until I left for college.”

Lizzie shuddered. She hadn’t realized before how much she actually knew about her parents’ work and how awful it still was to remember when she was compelled to jump to attention without ever really knowing why. She hadn’t ever told anyone else all about her parents. Oh, Marla knew quite a bit, but here she’d poured it all out to George’s mother. Gosh, she thought, Elaine would have been a great therapist.

“That must have been very hard for you.”

“Well, I had Sheila, my babysitter. She was wonderful. And I actually learned a lot from Lydia and Mendel. When I got to be a teenager, I manipulated them like crazy, and they were positively clueless. That was fun.”

“Did they like George?” Elaine asked, unable to imagine any parent not approving of George as a date for their daughter.

“Like George?” Lizzie repeated stupidly, not understanding.

“Yes, when he came with you at Thanksgiving.”

Lizzie thought for a moment. She’d never considered that before, what her parents might think of George. “I know it sounds weird, but Lydia was never around that day to introduce to George. And Mendel’s simply pathetic. He’s indifferent to everything but Lydia and his rats. Lydia’s much more critical, so maybe it’s better that she didn’t meet George. Anyway, he was my first boyfriend to darken their door since I started dating.”

“You didn’t bring any of the boys you dated home? I would have hated it if I’d never met any of George’s girlfriends.”

Lizzie suddenly wanted to know more about George’s other girlfriends, but didn’t know if she should ask Elaine about them. “Well, my parents didn’t care about anything I did, unless they planned to modify my behavior, so I tried never to do anything in front of them. I was always so careful. But here’s the kind of thing they did care about. Or at least Lydia did. When I was a freshman a boy named Dane Engel called me. According to Lydia, who answered the phone, he asked to speak with me. And that did it for him.”

“But why? I don’t get it.”

“Because one of Lydia’s pet peeves is that you should never say ‘talk with’ someone, it should be ‘talk to’ someone. She refused to let him talk to me and when she’d hung up, after basically saying he wasn’t welcome to call again, she told me why she’d done what she did. For my own good. My own good! Give me a fucking break. Oh, gosh, sorry—I guess it still bothers me.”

“No, no, no, that’s fine, don’t be sorry.”

“I think that’s one of the reasons I like George,” Lizzie told her. “He’s smart but not a snob. I get the feeling that even if I did something stupid, like say ‘between you and I,’ George might flinch but he wouldn’t kick me out of his life.”

“You’re absolutely right,” Elaine responded. “George seems to be endlessly forgiving. I could tell you horror stories about the mistakes Allan and I made as parents, but nothing seemed to rattle George enough to make him give up on us.”

Elaine changed the subject back to Mendel and Lydia. “Do you think your parents wanted you to be a psychologist too? Did they mind when you told them you were planning to major in English instead?”

“God, no. I think they probably feel that as long as they’re psychologists, nobody else needs to be.”

Elaine shook her head, but whether it was in disbelief or sympathy, Lizzie couldn’t tell. She was about to share some of her mother’s other strong dislikes with Elaine—Roget’s Thesaurus and fantasy trilogies were high on the list—but stopped when they heard Allan and George at the door.

That night they went out to a Chinese restaurant for dinner. This was the culminating tradition of the Goldrosens’ Christmases. “Our last meal,” Allan joked.

After the waiter left with their orders, Elaine picked up her bottle of Tsingtao beer. “I propose our first toast: to a wonderful time together this year and to us all being together next year, same time, same place. Only with the addition of Todd, because we miss him dreadfully.”

They clinked glasses and drank.

“Who’s next?”

“I am,” Allan said. “To Lizzie, who was a good sport and a wonderful guest. We’re so happy George brought you home for Christmas.”

“Hear, hear,” George and Elaine chorused.

“Well,” George said, “I was going to propose a toast to Lizzie too, Dad, so how about this: to Allan and Elaine, the best parents anyone could have.”

“Oh, Georgie, that’s wonderful you feel that way,” Elaine said, tearing up slightly. Allan took out his handkerchief and blew his nose.

“Can I do one?” Lizzie asked. “Or do you have to be a Goldrosen to participate?”

“You’re an honorary Goldrosen, so have at it,” George said.

“Okay.” She raised her glass. “First, George, I’m so glad you invited me. You can’t imagine how nervous I was about coming.” She turned to smile at Allan and Elaine. “Thank you both so much for everything. I can see why George is such a nice guy, having you both as parents.”

George thought that being a nice guy wasn’t exactly the ringing endorsement you want from your own true love, but Lizzie was so stingy with saying, or maybe fearful of saying, anything positive that George knew he had to be grateful for even that crumb.

Allan blew his nose again. Elaine reached out and took Lizzie’s hand. “You should have seen me the first time I met Gertie and Sam. I couldn’t even talk because my teeth were chattering and I was sure I was going to vomit all over their shoes.” Everyone laughed and Elaine went on, “I hope you’ll come back soon, Lizzie.”

Later, when they were maneuvering their chopsticks with varying degrees of facility (Lizzie was the most inept), Elaine started telling dentist stories.

“Now, Lizzie, I know you’ve never heard this story, but, George, I’m sure I’ve told you about Dr. Sidlowski before.” She turned to Lizzie and said, “He was my regular dentist’s partner. I went to him once, right before I left Montreal for Bryn Mawr because Dr. Gratz was on vacation or something. I’d broken a tooth after eating too many pieces of this really crusty sourdough bread at lunch. I was just beside myself—who breaks a tooth at age eighteen? Don’t answer that, George,” she said hastily as he started to speak. “It was a rhetorical question. Anyway, they took me in right away, and when Dr. Sidlowski asked me how it happened, of course I blamed the bread. But then he asked how many pieces of bread I’d had, and I told him three, which was agonizingly embarrassing. And then he said in this critical voice, ‘Well, clearly the first piece sensitized it, the second piece loosened it, and the third piece cracked it. Perhaps you should take a lesson from this.’ And I have. I almost never have three pieces of bread right in a row, and I certainly don’t when it’s that crusty sort of sourdough. I’m glad I never had to go back to him again.

“I wonder if any of his patients ever complained about the way he talked to them. I suspect there’s a way to find out. It’s that sort of question that keeps me up at night.”

“Nothing keeps you up at night, darling,” Allan said.

Elaine chuckled. “You’re right. But if I were the kind of person who did lie awake at night and ponder various questions, that’s what I would ponder. If Dr. Sidlowski was ever made aware of what an awful person he was. There I was, already suffering from guilt and shame, and look how he treated me, with more guilt and shame. Don’t ever be like that, George,” she ordered, but it was unnecessary to say that, because everyone at the table knew there was no way that George would ever commit the sin that Dr. Sidlowski had.

“There’s a book I really enjoyed that has a dentist in it,” Lizzie began, “called Do the Windows Open? Have you read it, Elaine? It’s by Julie Hecht. It’s a collection of linked short stories about this really neurotic woman. In one of the stories she’s at her dentist’s and . . .”

She paused. Should she continue? Okay, why not? she thought. It’s probably inappropriate but also really funny. Okay, whatever. I’m going to go for it. George loves me, right? Isn’t that what he said? I’ll think about what I’m going to do with that piece of information tomorrow or the next day. In any case, let him see the real me. Let them all see the kind of person I really am.

She began again. “So the dentist is drilling away, and, I can’t remember her exact words, but she’s musing to herself something like ‘Dentists have the highest suicide rate of everyone in the medical professions,’ and then she goes on to say, ‘Not high enough, in my opinion.’ For some reason I think that’s really funny.”

For several minutes after she finished, no one spoke. Finally Allan coughed. Elaine looked up from studying the remains of the Chinese food on her plate. “Are you getting a cold, Allan?”

George interrupted before his father could answer. “Hmm, I can see how people who hate going to the dentist might find that funny. And you know, it very subtly makes an excellent point: people with depressive personalities shouldn’t go into dentistry. Think about it: people come to you in extraordinary pain, you have to inflict pain to cure the original pain, and you’re working on something that’s only a bit bigger than a grain of rice, with little or no margin for error. I remember one of my teachers saying that what a dentist needed most was a steady hand, steady nerves, and an untroubled heart.”

Lizzie looked at him gratefully.

“That’s why we love George, isn’t it, Lizzie?” Elaine said somewhat mysteriously.

“Yes,” Lizzie said slowly. “I suppose it is.”

M’Ardon “Mardy” Preatty, built like a fire hydrant, was undrafted and later signed by the Lions after a so-so career at Clemson. Although he never became the game-changing pro player that his high school coach had predicted he’d be, season after season he managed to hold on to a spot on the team. Of course, the team as a whole wasn’t very good in any of the years he played for them. Lizzie occasionally saw him on television at the end of a lopsided game and she never failed to point him out to George, although she never went on to mention under what circumstances they’d met.

The other tackle suffered in comparison with Mardy Preatty, but then, almost any tackle playing on the same team as Mardy would. Leon Daly chose not to go to college, or perhaps he dropped out before graduation, and was last seen by Lizzie working at the local Toyota dealership, where he was a highly skilled and much-valued mechanic.

When Lizzie was little, Sheila used to tell her about watching the submarine races at Island Park with her boyfriend. It sounded really exciting to Lizzie: submarine races! Whoa! What submarine races were didn’t become clear to her until one morning in Tulsa when she and George were walking on the River Parks Trail and she wondered aloud if they had submarine races on the Arkansas River too. George looked at her and gulped loudly. At first Lizzie thought he was choking and regretted that she’d never learned how to do CPR, but then he started laughing. George was a laugher, all right—it was one of the things Lizzie loved about him. His was the sort of laugh that had people who heard him rolling on the floor, joined in a fellowship of mirth. Lizzie had obviously missed the joke, if a joke there was. In any event, George was bent over, chest heaving, hands on his knees. Every time his laughter seemed to be slowing down, he would gurgle something mostly indistinguishable that sounded to her like “submarines, Arkansas” and go off again. Finally, when he got himself more or less under control, he explained as you might explain to a young child.

“Lizzie, honey,” he began. “I have some breaking news for you. Submarines are underwater, right? So you can’t see them. Saying you’re watching a submarine race is a euphemism for making out.”

Oh, how embarrassing, Lizzie thought then, her face reddening. I am so glad I never told Jack about those stupid submarine races.

George was constantly surprised at how naive Lizzie was, how easy it was to tease her. His favorite Lizzie story, which he tried not to remind her of too often, had to do with IGA grocery stores. Passing one on their way home in Ann Arbor, Lizzie wondered aloud what the initials stood for.

“You know about the International Geophysical Association, right?” George asked, in the tone of voice that indicated that absolutely everyone knew and anyone who didn’t was impossibly lacking in smarts.

“I guess,” Lizzie said. “I mean, I sort of know what the words mean, especially ‘international’ and ‘association.’ Those I’m sure about. Why?”

“Their hundredth anniversary was about ten years ago, and they decided to start a chain of grocery stores to make some money for the group.”