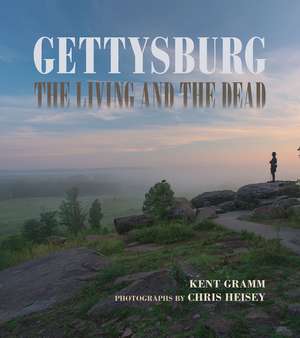

Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead

Autor Kent Gramm Fotograf Chris Heiseyen Limba Engleză Hardback – 16 iun 2019

In Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead, writer Kent Gramm and photographer Chris Heisey tell the famous battle’s story through the eyes of those who lived and died there. Unlike histories that simply recount the three furious days in July 1863, this book transports readers onto the battlefield and into the event’s historical echoes, making for a delightful, immersive experience.

Creative nonfiction, fiction, dramatic dialogue, and poetry combine with full-color photographs to convey the essential reality of the famous battlefield as a place both terrible and beautiful. The living and the dead contained here include Confederates and Yankees, soldiers and civilians, male and female, young and old. Visitors to the battlefield after 1863, both well known and obscure, provide the voices of the living. They include a female admiral in the U.S. Navy and a man from rural Virginia who visits the battlefield as a way of working through the death of his son in Iraq. The ghostly voices of the dead include actual participants in the battle, like a fiery colonel and a girl in Confederate uniform, as well as their representatives, such as a grieving widow who has come to seek her husband.

Utilizing light as a central motif and fourscore and seven voices to evoke how Gettysburg continues to draw visitors and resound throughout history, alternately wounding and stitching the lives it touches, Gramm’s words and Heisey’s photographs meld for a historical experience unlike any other. Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead offers a panoramic view wherein the battle and battlefield of Gettysburg are seen through the eyes of those who lived through it and died on it as well as those who have sought meaning at the site ever since.

Creative nonfiction, fiction, dramatic dialogue, and poetry combine with full-color photographs to convey the essential reality of the famous battlefield as a place both terrible and beautiful. The living and the dead contained here include Confederates and Yankees, soldiers and civilians, male and female, young and old. Visitors to the battlefield after 1863, both well known and obscure, provide the voices of the living. They include a female admiral in the U.S. Navy and a man from rural Virginia who visits the battlefield as a way of working through the death of his son in Iraq. The ghostly voices of the dead include actual participants in the battle, like a fiery colonel and a girl in Confederate uniform, as well as their representatives, such as a grieving widow who has come to seek her husband.

Utilizing light as a central motif and fourscore and seven voices to evoke how Gettysburg continues to draw visitors and resound throughout history, alternately wounding and stitching the lives it touches, Gramm’s words and Heisey’s photographs meld for a historical experience unlike any other. Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead offers a panoramic view wherein the battle and battlefield of Gettysburg are seen through the eyes of those who lived through it and died on it as well as those who have sought meaning at the site ever since.

Preț: 319.16 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 479

Preț estimativ în valută:

61.08€ • 63.53$ • 50.42£

61.08€ • 63.53$ • 50.42£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 22 martie-05 aprilie

Livrare express 11-15 martie pentru 48.37 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780809337330

ISBN-10: 0809337339

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 92

Dimensiuni: 210 x 235 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.86 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

ISBN-10: 0809337339

Pagini: 240

Ilustrații: 92

Dimensiuni: 210 x 235 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.86 kg

Ediția:1st Edition

Editura: Southern Illinois University Press

Colecția Southern Illinois University Press

Notă biografică

Kent Gramm is an adjunct professor of English at Gettysburg College. His prior works include November: Lincoln’s Elegy at Gettysburg, Gettysburg: A Meditation on War and Values, Somebody’s Darling: Essays on the Civil War, and two poetry collections. He edited Battle: The Nature and Consequences of Civil War Combat. His play Lincoln Lives was performed in Baton Rouge as part of Louisiana’s Lincoln Bicentennial Inauguration.

Chris Heisey has won awards for his photography and has published popular Civil War calendars. He contributed photographs to In the Footsteps of Grant and Lee: The Wilderness through Cold Harbor with text by Gordon Rhea and to Gettysburg: This Hallowed Ground with text by Kent Gramm.

Chris Heisey has won awards for his photography and has published popular Civil War calendars. He contributed photographs to In the Footsteps of Grant and Lee: The Wilderness through Cold Harbor with text by Gordon Rhea and to Gettysburg: This Hallowed Ground with text by Kent Gramm.

Extras

Prologue

The Photographer (1863)

Oh yes, we shifted the body. And yes, we positioned him somewhat, turning his face toward the camera. We found a musket and propped it up against that wall, suggesting a story—someone’s, possibly his. It is conceivable that blood from his ears and nose meant concussion. A Federal gunner could have cut his fuze so that a shell exploded precisely overhead, killing our young man. The blunt facts are indeed that he was in the battle and that he is dead. But of course we created a composition. What is art? Selection and arrangement. Photography is an art. A bloody face is only horrible. We didn’t mean only to frame the grotesqueness of war. Our photograph, our portrait, was not of gore—was not even of him, exactly; we meant to photograph his folks back home. Not their faces, but their love and grief. We tried to picture pathos and pity, and the loss his mother felt, his sister felt, perhaps a young and hopeful wife waiting. His body was insensate, empty, an object, but their sorrow, unspeakable, found expression in the photograph: a young man, someone’s darling, someone’s child—childhood innocence recalled in that repose—that’s what we meant. War is loss; war is families destroyed.

Oh yes, no doubt he was not innocent, and neither was his family. Could be he was the sharpshooter who murdered Hazlett and Weed. And Southern women were the backbone of the war; the rage of battle was partly their rage. None of us is innocent. But somewhere beside our murderousness, does there not flutter the better angel of our nature? Is there no light within? That is what we’re after, like all the portrait artists of the past. Our medium is light. The medium of everything is light. Without art, it’s all a hash of flesh and blood and gore. Our photograph shows nothing of the stench. Can you imagine what the odor was the day we photographed that boy? Horses and men unburied; flies in brazen billions. We vomited what little food we ate. Decay is everywhere; we’re dying now. Even Vermeer was forced to catch his light between the sausage and the privy, the rank sweat of a summer afternoon thickening the musty air in his studio. “In the midst of life, we are in death,” the old saying goes, but also in the midst of death, there’s life.

And so we bare its light; we make visible the invisible. It’s all murder: creation feeds upon creation, flesh devours flesh, and the wise die, Solomon wrote, no better than the fool. And yet, isn’t there something else—something essential, that is ordinarily unseen? It’s all here on this battlefield: cruelty and courage, senseless death and higher purpose, horror and nobility, the flesh and the spirit. Battle is life compacted. One little bit of light enters the camera, the eye, illuminates the dark, imprisoned soul, and the blind see.

Colonel Cross

The Rebel bastard shot me from that rock—a vicious, futile act that earned him a body full of bullets from my men. To shoot an unarmed officer, even amid the rage of battle, is nothing but brute stupidity. I always told my boys to kill the ones who carry muskets; the officers will be replaced, perhaps by better ones who’ve learned from their commanders’ mistakes. I had a higher opinion of Rebel infantrymen than of their officers, who had at least some pretense of education and should have known better than to fight for what they were fighting for.

But it is my considered judgment now that the whole lot of them are imbeciles with little more claim to being human than possessing facial hair and Bibles. The uniformed dog on that rock might have believed he did God’s will by shooting Yankee officers. They could not be doing what they are doing, fighting to keep an entire race in chains, without their Bible-thumping preachers shouting God’s approval—no, His outright favor, and His holy desire to see as many Yankee Philistines murdered on His altar as could be effected by those Christian gentlemen—illiterate, armpit-scratching gentlemen. In them, Christianity is an obscenity—hypocrisy drawled in a ridiculous fog of whiskey. Without their preachers, they could not rush in and die like lunatics in front of my men, line after line coming at us with that childish yell of theirs, swarming forward in the hope of everlasting bliss in a non-Yankee heaven, where black angels, no doubt, light up their seegars and serve them juleps for ever and ever amen, hallelujah! And the Good Lord sending all of us mudsills to the place of sulphur, fire, and brimstone. We’ll see. We’ll see if there’s a heaven or a hell, and if there is, we’ll see what Jesus thinks of gentlemen who whip mere children and women to do their work for them. We might not be gentlemen, but we do our own work!

I can sense that you are the reconciling sort, but even you can see that all this mayhem came about because the South would not suffer themselves to lose an election, and for their own self-interest, therefore, they tore at the very principle of democratic government so they could keep their so-called property. We Northerners entered the war too kindly. The Rebels hated us right off, and won the battles, because war is not Sunday school. We didn’t understand that when you take up the cross of war, you must carry it to Calvary. You must abandon your delights and your beliefs, and descend into hell, with no angels to comfort you except your musket and bayonet. I taught my men to hate the gentlemen—“The Prince of Darkness is a gentleman,” you read in Shakespeare. And the war itself taught my soldiers to hate. If the Rebels yelled like banshees, then we would yell like Indians! The Rebels fix bayonets; then we fix bayonets and charge first. You may start a war with prayer books, but you must finish it with steel.

I knew that I would die out here. “He who lives by the sword shall die by the sword.” Always before battle I would wrap a red kerchief around my bald head to tell my men to be about their business. This time I asked my orderly if he had a black bandanna, and I tied it tight around my head, as if to tell my boys, Don’t be dismayed. We are going to die, quite a few of us, but we will give them hell first, and after we are gone, you rest must drive it home. If war begins in church, it ends in the graveyard. It ends out here, with nothing in between but rage. Give it to them! Give them the bayonet! Let them come on. Shoot the bastards down, and keep your prayers to yourselves until afterwards. Come on, men! Give them some New Hampshire hell! This time we’ve got them on the run! After them!

Major Dunlop’s Hat

That’s it right there, perfectly preserved. You see the ragged hole where a fragment of shell went in and where his soul went out. A little blood is visible inside, though it’s almost black, but I’d rather not unlock the glass case to take it out and show you. Humidity and temperature are controlled. One time a member of his family came in and said she had the right to it. But I said the major’s hat belongs to the public, owned by the nation for which he gave his life. It belongs to the ages. She sued my museum, claiming that we charged admission and were a private, for-profit company. We argued that her claim of descent from Major Dunlop was fraudulent, because he had no children. Well, the hat is here, as you can see. It’s one of our most popular attractions.

Actually, we didn’t know that Major Dunlop had no children, but the burden of proof was on her, and she was no historian. She came to the hearing drunk, or probably on some medication, which did her case no good. All these little things affect the court, which is to say the judge, who is a human being first to last. Essentially, there is no justice. Or at any rate, there is no justice in this world. Justice might be blind, meaning impartial, but I think she’s just stone blind, and subject to a pinch now and then.

What’s that? I have no idea whether Major Dunlop died for justice. He died for orders, sure enough. For Liberty and Union I might say, but not being a New Englander, he most likely didn’t die to abolish slavery. Died to prove he was no coward. He died for his friends is a pretty safe bet, because that’s usually what it comes down to in battle. But as to some abstraction—justice, or what have you—one’s best not speculating is how I view it. We load on those poor nineteenth-century people a lot of our own ideas, our own hopes and wishes.

Yes, I mentioned Major Dunlop’s soul. Does that surprise you? Because you think I have none myself. I’ll pass on feeling insulted, because I think the question is a fair one. I mean the question you implied, whether we have souls. I sense your assumption is that we do. But I ask you what it is. If Major Dunlop is somewhere now, alive and well, it’s not as Major Dunlop. Maybe a luminescent orb, some eerie floating thing the ghost hunters claim to see. Or he has reentered earthly life as a plumber in Detroit or a rickshaw driver in Calcutta—with no thought of Major Charles Dunlop in his head. Who is he, then? Maybe he’s a Civil War buff like you now. Or, say, he could be me.

Now that would be justice. But if there’s justice, who’s holding the scales? Who’s putting a thumb on one of the plates? Let’s say the major died for justice. For what? Where is the justice for which the major so nobly died? Do we have it? So he died for nothing, if he died for justice, which, if I remember my high school algebra, means justice is nothing. I mean as a thing in itself. Maybe it’s fairness, whatever that is. He died, basically, for people like me to figure out what justice and fairness are. He died, and I’m left holding his hat.

What does that mean? It means that he handed the whole ball of wax to me. Justice is what I say it is. I decide. I am “We the People,” and I’m the judge and jury, not someone else, a king or a duke or a dictator. I’m basically corrupt. I’ll grant you that. And I’m ignorant. The only person less qualified than I am to govern me is someone else. Died for justice? Well, he died for me. That’s what I mean when I say I’m holding his hat. And I’m not letting go.

The Photographer (1863)

Oh yes, we shifted the body. And yes, we positioned him somewhat, turning his face toward the camera. We found a musket and propped it up against that wall, suggesting a story—someone’s, possibly his. It is conceivable that blood from his ears and nose meant concussion. A Federal gunner could have cut his fuze so that a shell exploded precisely overhead, killing our young man. The blunt facts are indeed that he was in the battle and that he is dead. But of course we created a composition. What is art? Selection and arrangement. Photography is an art. A bloody face is only horrible. We didn’t mean only to frame the grotesqueness of war. Our photograph, our portrait, was not of gore—was not even of him, exactly; we meant to photograph his folks back home. Not their faces, but their love and grief. We tried to picture pathos and pity, and the loss his mother felt, his sister felt, perhaps a young and hopeful wife waiting. His body was insensate, empty, an object, but their sorrow, unspeakable, found expression in the photograph: a young man, someone’s darling, someone’s child—childhood innocence recalled in that repose—that’s what we meant. War is loss; war is families destroyed.

Oh yes, no doubt he was not innocent, and neither was his family. Could be he was the sharpshooter who murdered Hazlett and Weed. And Southern women were the backbone of the war; the rage of battle was partly their rage. None of us is innocent. But somewhere beside our murderousness, does there not flutter the better angel of our nature? Is there no light within? That is what we’re after, like all the portrait artists of the past. Our medium is light. The medium of everything is light. Without art, it’s all a hash of flesh and blood and gore. Our photograph shows nothing of the stench. Can you imagine what the odor was the day we photographed that boy? Horses and men unburied; flies in brazen billions. We vomited what little food we ate. Decay is everywhere; we’re dying now. Even Vermeer was forced to catch his light between the sausage and the privy, the rank sweat of a summer afternoon thickening the musty air in his studio. “In the midst of life, we are in death,” the old saying goes, but also in the midst of death, there’s life.

And so we bare its light; we make visible the invisible. It’s all murder: creation feeds upon creation, flesh devours flesh, and the wise die, Solomon wrote, no better than the fool. And yet, isn’t there something else—something essential, that is ordinarily unseen? It’s all here on this battlefield: cruelty and courage, senseless death and higher purpose, horror and nobility, the flesh and the spirit. Battle is life compacted. One little bit of light enters the camera, the eye, illuminates the dark, imprisoned soul, and the blind see.

Colonel Cross

The Rebel bastard shot me from that rock—a vicious, futile act that earned him a body full of bullets from my men. To shoot an unarmed officer, even amid the rage of battle, is nothing but brute stupidity. I always told my boys to kill the ones who carry muskets; the officers will be replaced, perhaps by better ones who’ve learned from their commanders’ mistakes. I had a higher opinion of Rebel infantrymen than of their officers, who had at least some pretense of education and should have known better than to fight for what they were fighting for.

But it is my considered judgment now that the whole lot of them are imbeciles with little more claim to being human than possessing facial hair and Bibles. The uniformed dog on that rock might have believed he did God’s will by shooting Yankee officers. They could not be doing what they are doing, fighting to keep an entire race in chains, without their Bible-thumping preachers shouting God’s approval—no, His outright favor, and His holy desire to see as many Yankee Philistines murdered on His altar as could be effected by those Christian gentlemen—illiterate, armpit-scratching gentlemen. In them, Christianity is an obscenity—hypocrisy drawled in a ridiculous fog of whiskey. Without their preachers, they could not rush in and die like lunatics in front of my men, line after line coming at us with that childish yell of theirs, swarming forward in the hope of everlasting bliss in a non-Yankee heaven, where black angels, no doubt, light up their seegars and serve them juleps for ever and ever amen, hallelujah! And the Good Lord sending all of us mudsills to the place of sulphur, fire, and brimstone. We’ll see. We’ll see if there’s a heaven or a hell, and if there is, we’ll see what Jesus thinks of gentlemen who whip mere children and women to do their work for them. We might not be gentlemen, but we do our own work!

I can sense that you are the reconciling sort, but even you can see that all this mayhem came about because the South would not suffer themselves to lose an election, and for their own self-interest, therefore, they tore at the very principle of democratic government so they could keep their so-called property. We Northerners entered the war too kindly. The Rebels hated us right off, and won the battles, because war is not Sunday school. We didn’t understand that when you take up the cross of war, you must carry it to Calvary. You must abandon your delights and your beliefs, and descend into hell, with no angels to comfort you except your musket and bayonet. I taught my men to hate the gentlemen—“The Prince of Darkness is a gentleman,” you read in Shakespeare. And the war itself taught my soldiers to hate. If the Rebels yelled like banshees, then we would yell like Indians! The Rebels fix bayonets; then we fix bayonets and charge first. You may start a war with prayer books, but you must finish it with steel.

I knew that I would die out here. “He who lives by the sword shall die by the sword.” Always before battle I would wrap a red kerchief around my bald head to tell my men to be about their business. This time I asked my orderly if he had a black bandanna, and I tied it tight around my head, as if to tell my boys, Don’t be dismayed. We are going to die, quite a few of us, but we will give them hell first, and after we are gone, you rest must drive it home. If war begins in church, it ends in the graveyard. It ends out here, with nothing in between but rage. Give it to them! Give them the bayonet! Let them come on. Shoot the bastards down, and keep your prayers to yourselves until afterwards. Come on, men! Give them some New Hampshire hell! This time we’ve got them on the run! After them!

Major Dunlop’s Hat

That’s it right there, perfectly preserved. You see the ragged hole where a fragment of shell went in and where his soul went out. A little blood is visible inside, though it’s almost black, but I’d rather not unlock the glass case to take it out and show you. Humidity and temperature are controlled. One time a member of his family came in and said she had the right to it. But I said the major’s hat belongs to the public, owned by the nation for which he gave his life. It belongs to the ages. She sued my museum, claiming that we charged admission and were a private, for-profit company. We argued that her claim of descent from Major Dunlop was fraudulent, because he had no children. Well, the hat is here, as you can see. It’s one of our most popular attractions.

Actually, we didn’t know that Major Dunlop had no children, but the burden of proof was on her, and she was no historian. She came to the hearing drunk, or probably on some medication, which did her case no good. All these little things affect the court, which is to say the judge, who is a human being first to last. Essentially, there is no justice. Or at any rate, there is no justice in this world. Justice might be blind, meaning impartial, but I think she’s just stone blind, and subject to a pinch now and then.

What’s that? I have no idea whether Major Dunlop died for justice. He died for orders, sure enough. For Liberty and Union I might say, but not being a New Englander, he most likely didn’t die to abolish slavery. Died to prove he was no coward. He died for his friends is a pretty safe bet, because that’s usually what it comes down to in battle. But as to some abstraction—justice, or what have you—one’s best not speculating is how I view it. We load on those poor nineteenth-century people a lot of our own ideas, our own hopes and wishes.

Yes, I mentioned Major Dunlop’s soul. Does that surprise you? Because you think I have none myself. I’ll pass on feeling insulted, because I think the question is a fair one. I mean the question you implied, whether we have souls. I sense your assumption is that we do. But I ask you what it is. If Major Dunlop is somewhere now, alive and well, it’s not as Major Dunlop. Maybe a luminescent orb, some eerie floating thing the ghost hunters claim to see. Or he has reentered earthly life as a plumber in Detroit or a rickshaw driver in Calcutta—with no thought of Major Charles Dunlop in his head. Who is he, then? Maybe he’s a Civil War buff like you now. Or, say, he could be me.

Now that would be justice. But if there’s justice, who’s holding the scales? Who’s putting a thumb on one of the plates? Let’s say the major died for justice. For what? Where is the justice for which the major so nobly died? Do we have it? So he died for nothing, if he died for justice, which, if I remember my high school algebra, means justice is nothing. I mean as a thing in itself. Maybe it’s fairness, whatever that is. He died, basically, for people like me to figure out what justice and fairness are. He died, and I’m left holding his hat.

What does that mean? It means that he handed the whole ball of wax to me. Justice is what I say it is. I decide. I am “We the People,” and I’m the judge and jury, not someone else, a king or a duke or a dictator. I’m basically corrupt. I’ll grant you that. And I’m ignorant. The only person less qualified than I am to govern me is someone else. Died for justice? Well, he died for me. That’s what I mean when I say I’m holding his hat. And I’m not letting go.

Recenzii

"The best aspect of Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead is the bravery of the author to tell his stories and poems through a broad range of voices. Both Union and Confederate soldiers are portrayed, sometimes with sympathy towards their enemies, often with the passions and hatreds of the war on full display."—H-Net Reviews

"This volume deftly combines commentary with memorable images to transport readers onto the battlefield and into the event's historical echoes, making for a delightful, immersive experience."—James A Cox, Midwest Book Review

“The rich trove of insightful prose and lyric poetry vignettes in Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead are evidence that Kent Gramm’s sensibility, intellect, and style have produced the masterwork of one of our finest writers. And Chris Heisey’s ninety-one distinctive photographs provide imaginative perspectives on the battlefield that inspire me to say they are among the finest of the thousands of such photographs I have seen.”—David Madden, author of Sharpshooter: A Novel of the Civil War

“This is an exquisite, original, evocative book. Writer Gramm and photographer Heisey have joined in a luminous alliance of word and picture to celebrate and commemorate people and places of Gettysburg. Their collaboration elegantly fuses the voices and tones of fourscore and seven speakers, past and present, with the shadings and colors of battlefield images made in all weathers and seasons, at all times of day. Lincoln spoke of consecration far above our poor power to add or detract. But this book is a powerful monument to the devotion he urged.”—Stephen Cushman, author of Belligerent Muse: Five Northern Writers and How They Shaped Our Understanding of the Civil War

“Gettysburg—the place and the battle—is offered here in a kind of fifth dimension, a remarkable assembly of haunts, gripping and moving, that is very hard to put down.”—Stephen W. Sears, author of Gettysburg

“Gramm and Heisey have collaborated to produce a moving, thought-provoking, and fascinating literary and photographic narrative destined to enthrall not only readers already interested in the American Civil War but the general public as well. This original presentation is a masterpiece of creative writing merged with equally creative photography. Hats off to Gramm and Heisey for opening our eyes to new ways of thinking about a topic that many readers mistakenly believed had already been thoroughly explored.”—Gordon C. Rhea, author of On to Petersburg: Grant and Lee, June 4–15, 1864

“Gramm and Heisey succeed in producing a work that is emotionally diverse and illustrates their love and sensitivity for the battlefield and all who feel connected to that hallowed space.”—Eric P. Totten, H-War, H-Net Reviews

"This volume deftly combines commentary with memorable images to transport readers onto the battlefield and into the event's historical echoes, making for a delightful, immersive experience."—James A Cox, Midwest Book Review

“The rich trove of insightful prose and lyric poetry vignettes in Gettysburg: The Living and the Dead are evidence that Kent Gramm’s sensibility, intellect, and style have produced the masterwork of one of our finest writers. And Chris Heisey’s ninety-one distinctive photographs provide imaginative perspectives on the battlefield that inspire me to say they are among the finest of the thousands of such photographs I have seen.”—David Madden, author of Sharpshooter: A Novel of the Civil War

“This is an exquisite, original, evocative book. Writer Gramm and photographer Heisey have joined in a luminous alliance of word and picture to celebrate and commemorate people and places of Gettysburg. Their collaboration elegantly fuses the voices and tones of fourscore and seven speakers, past and present, with the shadings and colors of battlefield images made in all weathers and seasons, at all times of day. Lincoln spoke of consecration far above our poor power to add or detract. But this book is a powerful monument to the devotion he urged.”—Stephen Cushman, author of Belligerent Muse: Five Northern Writers and How They Shaped Our Understanding of the Civil War

“Gettysburg—the place and the battle—is offered here in a kind of fifth dimension, a remarkable assembly of haunts, gripping and moving, that is very hard to put down.”—Stephen W. Sears, author of Gettysburg

“Gramm and Heisey have collaborated to produce a moving, thought-provoking, and fascinating literary and photographic narrative destined to enthrall not only readers already interested in the American Civil War but the general public as well. This original presentation is a masterpiece of creative writing merged with equally creative photography. Hats off to Gramm and Heisey for opening our eyes to new ways of thinking about a topic that many readers mistakenly believed had already been thoroughly explored.”—Gordon C. Rhea, author of On to Petersburg: Grant and Lee, June 4–15, 1864

“Gramm and Heisey succeed in producing a work that is emotionally diverse and illustrates their love and sensitivity for the battlefield and all who feel connected to that hallowed space.”—Eric P. Totten, H-War, H-Net Reviews

Descriere

Creative nonfiction, fiction, dramatic dialogue, and poetry combine with full-color photographs to convey the essential reality of the famous battlefield as a place both terrible and beautiful.