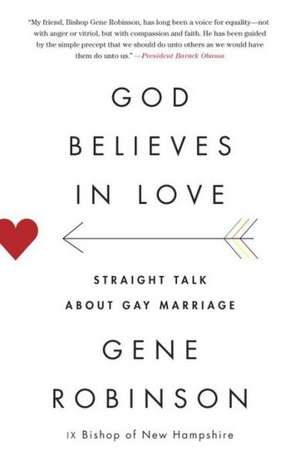

God Believes in Love: Straight Talk about Gay Marriage

Autor Gene Robinsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 3 iun 2013

Robinson holds the religious text of the Bible to be holy and sacred and the ensuing two millennia of church history to be relevant to the discussion. He is equally familiar with the secular and political debate about gay marriage going on in America today, and is someone for whom same-sex marriage is a personal issue; Robinson was married to a woman for fourteen years and is a father of two children and has been married to a man for the last four years of a twenty-five-year relationship.

Robinson has a knack for taking complex and controversial issues and addressing them in plain direct language, without using polemics or ideology, putting forth his argument for gay marriage, and bringing together sacred and secular points of view.

Preț: 67.84 lei

Preț vechi: 81.74 lei

-17% Nou

Puncte Express: 102

Preț estimativ în valută:

12.98€ • 13.58$ • 10.78£

12.98€ • 13.58$ • 10.78£

Disponibilitate incertă

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307948090

ISBN-10: 0307948099

Pagini: 196

Dimensiuni: 139 x 196 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0307948099

Pagini: 196

Dimensiuni: 139 x 196 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Gene Robinson was born and raised in Lexington, Kentucky, and graduated from the University of the South with a B.A. in American studies and history. He completed the M.Div. degree in 1973 at the General Theological Seminary in New York, and was ordained deacon and then priest. Having served as Canon to the Ordinary (assistant to the bishop) for nearly eighteen years, he was elected bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire in 2003. He retired as bishop in January 2013. The author of three AIDS curricula for youth, he is also the recipient of numerous awards from civil, human, and LGBT rights organizations. Robinson is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress in Washington, DC.

Extras

Chapter 1

Why Gay Marriage Now?

I was born in 1947. Homosexuality was hardly ever referred to in polite conversation, and even when it was, it was always in a whisper. “Gay” wasn’t even a word yet used to mean “homosexual.” Veiled references were either polite (“he’s a bit ‘that way,’ isn’t he?”) or derogatory and stereotypical (“he’s a bit ‘light in the loafers,’ don’t you think?”).

Homosexuality was something known to exist in certain exotic communities—mostly among actors and beat poets like Allen Ginsberg. No one in the hinterlands knew of the Mattachine Society for gay men and the Daughters of Bilitis for lesbians, secretive, emerging gay organizations in the 1950s on the liberal coasts. Certainly no one dreamed that romantic movie icons like Rock Hudson and James Dean, who were leading men wooing Hollywood’s most beautiful women, were homosexual.

Those in my generation could go through their entire lives without ever being asked the question, “Are you straight or gay?” It simply wasn’t on the radar screen for most Americans. Nor was it on mine.

It is hard to describe, then, the isolation I experienced as a boy when I started feeling “different.” There was no language to put around it. I wouldn’t have imagined that anyone else in the world was feeling what I was feeling. But I knew, from an early age, that I was different.

It didn’t help when my uncle Buck started calling me a “sissy.” I’m sure he wasn’t thinking “homosexual,” but he did seem to sense that I was different, not like his own son or other boys. “Effeminate,” he might have said, if he had even known the word. Not like the masculine boy I was supposed to be. I hated him, and I feared him, because he seemed to know my little, horrifying secret, and he would communicate it to the world at our family gatherings, with all the cruelty he could muster.

The only place homosexuality was discussed, albeit in a veiled and cryptic way, was at church. From time to time, there would be diatribes about “a man lying with a man” being an abomination. While I had never, ever gone as far as imagining lying with another man, somehow I took these sermons personally. I didn’t need any more fear and isolation in my life. But these sermons, for reasons I couldn’t explain, added the fear that I might be an “abomination” to the God of all creation.

Getting beaten up in the backyard at a classmate’s house party didn’t help. It was nothing truly dangerous, but I did not defend myself when “friends” began to rough me up. It must be true, I thought. I really am a sissy. Not a man. And to this day I can remember the shame I felt at my father’s obvious disappointment that I had not stood up for myself.

Thirty, even twenty years ago, most Americans would have told you that they didn’t know anyone gay. They might have wondered, and even joked, about their weird uncle Harold, who acted a bit strange, even effeminate. And they might have mentioned, usually with good humor and genuine affection, those two ladies who have lived at the end of the street forever—you know, the ones who keep their lawn so nice?! But most Americans would have been telling the truth about not personally knowing anyone who acknowledged his or her same-gender attraction, not to mention doing so with pride and dignity.

While the riot at the Stonewall Inn in New York officially galvanized the modern gay rights movement, and people began to understand more fully that there were homosexuals in the world, it was the AIDS crisis of the 1980s that alerted people to the presence in their midst of men who had sex with men. It was in 1982 that The New York Times reported on a new phenomenon: growing numbers of men were dying of diseases previously almost unheard of. These opportunistic infections, normally kept at bay by a healthy immune system, were ravaging these previously healthy men. And these afflicted men were homosexuals. The word “gay” had come into the lexicon by this time, and it was used to describe these medical anomalies: gay cancer.

As men started to get sick, very sick, they began calling home from San Francisco, West Hollywood, and New York. They were calling their parents and brothers and sisters to say that they were dying. Yes, I have the “gay cancer.” Yes, I’m gay—and my “friend,” whom you have come to enjoy and love over the years, is my lover. And yes, he’s taking care of me. Except that he’s getting sick too. And dying, like me.

Men from little towns and hamlets all over America who had lived the “gay life” in secret, in faraway places, were calling home to say, “I’m sick with the gay disease.” And in countless homes all across America, mothers and fathers and siblings knew for the first time—or had their suspicions confirmed—that their son or brother was gay.

Lesbians were increasingly outed by the same experience. Having also moved to places of acceptance and affirmation in large cities, they had come to know their gay brothers who were now becoming sick. Many of them took care of their seriously ill gay friends. Many began to advocate for AIDS funding and treatment. Many sat with their gay friends and listened to the devastating fallout from coming-out to their parents. Many shared the pain of coming clean about who they were and whom they loved. And as a result, many of them felt called to come out to their own parents as lesbian—partly in solidarity with their gay brothers, and partly because they too wanted to live free from keeping secrets from the families they loved.

Increasingly, even those not infected with the virus that came to be known as HIV wanted this same freedom. Despite the terrible consequences of coming out experienced by many, there were enough success stories to make them wonder, “What if I came out to my parents? Would they still love me?” And so, in ever larger numbers, the calls or visits home began, for the purpose of coming out.

In countless living rooms across America, beloved sons and daughters sat down, hearts in their throats, to say, “Mom, Dad. I’m gay.” It is hard to describe the cataclysmic, earthquake-like effect this had on families. Something simply unthinkable had been revealed, although to be honest, many parents had wondered why their son or daughter hadn’t married, or didn’t even seem to be dating, or simply had become silent about his or her personal life. Now it all made sense—terrible and horrifying sense. Those whose sons were now sick with AIDS had a double whammy: they hardly knew which to grieve first, the revelation that they had a gay son or the fact that he was dying at age twenty-eight.

Remember how social change happens. Each of us has a worldview that pretty much interprets the world for us, puts our personal and public experiences in some kind of rational and understandable order. That worldview works fairly well for a period of time. Then something happens that renders it insufficient. Something happens that can’t be fit into life as we have known and interpreted it. Something so shocking and disturbing as to shake the very foundations of who we thought we were.

Parents across America knew they loved their sons. They were proud of them and bragged to relatives and friends about what they were accomplishing, albeit far away in San Francisco. They had learned not to ask too many personal questions, and there was often a feeling of something unspoken. But still, what a wonderful son he was!

And now this! Was he going to stay where he was, nursed by his “partner”? (What a strange new meaning to the word!) How could a parent explain to the neighbors these now-frequent trips to San Francisco, which clearly went beyond the annual visit? Or was he going to come home to die, to be cared for by his parents? And how could that be explained to nosy relatives—especially when they saw how emaciated he looked, with the telltale, dark reddish splotches of Kaposi’s Sarcoma beginning to appear on his face? The son’s coming-out to his parents often involved the parents’ coming-out to their family and friends—not a willing, voluntary coming-out as having a gay son, but one born of necessity and tragedy.

And so the parents were having an experience for which their comfortable worldview had not prepared them. They knew two things for sure: their son was gay, and they loved him. More often than not, this felt like being placed between a rock and a hard place. Being gay (what a strange word for a condition so tragic and so morally disgusting) was a terrible thing. But this was their son, whom they had always loved. And the family was thrown into emotional chaos, a battle between two competing truths. Over time, each family resolved this issue. For the unlucky ones, the gay son was disowned, pushed away, and condemned out of moral outrage and (usually) religious rigidity. For the lucky ones, the urge to love overcame the need to judge, and with tentative and uncertain steps these parents began to change their long-held worldview, to allow for the possibility that their child’s homosexuality might not be the end of the world, nor would it precipitate the end of their love for him.

In biblical imagery, the scales had fallen from their eyes. What was previously unknown or only suspected was confirmed. Now they knew. And so would everyone else. Parents would often experience an isolation of their own, fearing to tell friends and family the truth, lest they be blamed for their son’s homosexuality. After all, wasn’t it something they had done, or not done, that had made him this way? What would people think of them?

Simultaneous with the emergence of AIDS, and largely because of it, gay organizations took on a new courage and boldness. Groups like Act Up loudly proclaimed the presence of gay people: “We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it!” Those who resisted a vigorous response to the HIV/AIDS crisis, including gay men and lesbians who were unaffected by the pandemic, were challenged by “Silence = Death.” Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician to be elected to public office in the previous decade, had said, “Coming-out is the most political thing you can do.” It turned out he was right. And as more and more gay men and lesbians came out to their families and friends—not because they had to, but because they wanted to—Americans realized that they knew someone gay or lesbian. And our world irrevocably changed.

In the years to come, other sexual minorities would be inspired to follow the lead of their gay brothers and lesbian sisters. People who were open to physical intimacy with people of either gender would come out as bisexual. And then we began to hear from people whose physical characteristics and genitals indicated one gender but whose feelings and inner being indicated the opposite. Transgender people are still in the early stages of coming-out, but because their very existence challenges our comfortable definitions of gender identity and expression (even for gay men and lesbians), it has been a difficult journey forward. The murder rate for open and honest transgender people is horrifyingly high. It is still a dangerous world for those who have come to know and acknowledge themselves as transgender. Transgender and bisexual people have joined their gay brothers and lesbian sisters in confronting their families with the truth about their lives.

High school and college reunions have often provided an opportunity for learning about people (not to mention humor!). It is very common for someone to show up at his or her reunion not with a spouse of the opposite gender but with a same-gender partner. This can come as a shock to a former classmate who only remembers you as the good-looking, girl-chasing captain of the football team. For some, it’s simply not on their radar screen. When Mark and I attended his reunion at Middlebury College and I was introduced to a friend as his “partner,” the clueless friend asked what business we were in.

Even more dramatic is the reunion where good ol’ Jack arrives back at his alma mater as Jacqueline, now a woman and looking pretty damn good! As the stigma against transgender people diminishes and more transgender people find the world safe enough to tell their stories, we will see more of this.

As much as some would like all this to have never occurred, or for the world to go back to a “simpler” time when “men were men, and women were women, and everyone knew the difference,” the fact is that toothpaste is never going back into the tube. This is a new reality, and like it or not, the world has to deal with it.

With this newly acknowledged existence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in our midst—members of our families, next-door neighbors, former classmates, colleagues in the workplace, not to mention on TV and in the culture—a new awareness of the needs and aspirations of this group is emerging. With it, there is a growing understanding that this group has been discriminated against, not merely in a personal, individual way, but also in a societal structure that systematically rewards heterosexuals and punishes homosexuals, just as whites have been rewarded at the expense of blacks and men rewarded at the expense of women. Beyond the personal issue of whether kind and compassionate treatment will be accorded gay individuals, this systemic discrimination embedded in our societal norms, laws, and rights is a justice issue that begs for redress.

Increasingly, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are demanding that they be treated with the same dignity and afforded the same responsibilities and rights as their heterosexual fellow citizens. Public policies are beginning to change. We’ve seen the end of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in the military, and the White House has announced that it will no longer defend in court the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), believing it to be unconstitutional. There is even increased opposition to DOMA in Congress. Such systemic discrimination now seems antiquated and unfair to many. Challenges to state constitutional amendments barring gay marriage (and in some states, even the outlawing of civil unions and domestic partnerships between people of the same gender) are under way. While there is still opposition to changing these policies, it is now a foregone conclusion that these policies are worthy of a vigorous debate and that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people may indeed have a legitimate and equal claim on the rights and privileges of citizenship in America.

In this context, the demand for marriage equality is not surprising. After all, marriage is the State’s way of promoting stability within society. Married couples are rewarded for their mutual commitments with tax benefits, insurance coverage, inheritance laws, and a host of other financial benefits. We are now living in a time of disconnect for many gay and lesbian couples who are legally married in their state of residence but still denied federal rights (including Social Security benefits and protections) because of the Defense of Marriage Act at the federal level.

But this debate isn’t just about financial advantage. It’s also about respect. Mutually committed couples of the same gender are increasingly demanding the societal and social respect that accrues from marriage—not just in America, but in many countries around the world. The burden is gradually but dramatically shifting from those who are arguing for equal treatment under the law to those who are having to explain why this equal treatment should not be the case. Perhaps no other shift in public opinion and public policy has occurred in such a short period of time, historically speaking. And we find ourselves talking about gay marriage in a way that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago. It is a conversation that is both particular (about rights, privileges, responsibilities, and benefits) and symbolic (about equal respect from the law and equal justice under the law). It is a conversation whose time has come.

Why Gay Marriage Now?

I was born in 1947. Homosexuality was hardly ever referred to in polite conversation, and even when it was, it was always in a whisper. “Gay” wasn’t even a word yet used to mean “homosexual.” Veiled references were either polite (“he’s a bit ‘that way,’ isn’t he?”) or derogatory and stereotypical (“he’s a bit ‘light in the loafers,’ don’t you think?”).

Homosexuality was something known to exist in certain exotic communities—mostly among actors and beat poets like Allen Ginsberg. No one in the hinterlands knew of the Mattachine Society for gay men and the Daughters of Bilitis for lesbians, secretive, emerging gay organizations in the 1950s on the liberal coasts. Certainly no one dreamed that romantic movie icons like Rock Hudson and James Dean, who were leading men wooing Hollywood’s most beautiful women, were homosexual.

Those in my generation could go through their entire lives without ever being asked the question, “Are you straight or gay?” It simply wasn’t on the radar screen for most Americans. Nor was it on mine.

It is hard to describe, then, the isolation I experienced as a boy when I started feeling “different.” There was no language to put around it. I wouldn’t have imagined that anyone else in the world was feeling what I was feeling. But I knew, from an early age, that I was different.

It didn’t help when my uncle Buck started calling me a “sissy.” I’m sure he wasn’t thinking “homosexual,” but he did seem to sense that I was different, not like his own son or other boys. “Effeminate,” he might have said, if he had even known the word. Not like the masculine boy I was supposed to be. I hated him, and I feared him, because he seemed to know my little, horrifying secret, and he would communicate it to the world at our family gatherings, with all the cruelty he could muster.

The only place homosexuality was discussed, albeit in a veiled and cryptic way, was at church. From time to time, there would be diatribes about “a man lying with a man” being an abomination. While I had never, ever gone as far as imagining lying with another man, somehow I took these sermons personally. I didn’t need any more fear and isolation in my life. But these sermons, for reasons I couldn’t explain, added the fear that I might be an “abomination” to the God of all creation.

Getting beaten up in the backyard at a classmate’s house party didn’t help. It was nothing truly dangerous, but I did not defend myself when “friends” began to rough me up. It must be true, I thought. I really am a sissy. Not a man. And to this day I can remember the shame I felt at my father’s obvious disappointment that I had not stood up for myself.

Thirty, even twenty years ago, most Americans would have told you that they didn’t know anyone gay. They might have wondered, and even joked, about their weird uncle Harold, who acted a bit strange, even effeminate. And they might have mentioned, usually with good humor and genuine affection, those two ladies who have lived at the end of the street forever—you know, the ones who keep their lawn so nice?! But most Americans would have been telling the truth about not personally knowing anyone who acknowledged his or her same-gender attraction, not to mention doing so with pride and dignity.

While the riot at the Stonewall Inn in New York officially galvanized the modern gay rights movement, and people began to understand more fully that there were homosexuals in the world, it was the AIDS crisis of the 1980s that alerted people to the presence in their midst of men who had sex with men. It was in 1982 that The New York Times reported on a new phenomenon: growing numbers of men were dying of diseases previously almost unheard of. These opportunistic infections, normally kept at bay by a healthy immune system, were ravaging these previously healthy men. And these afflicted men were homosexuals. The word “gay” had come into the lexicon by this time, and it was used to describe these medical anomalies: gay cancer.

As men started to get sick, very sick, they began calling home from San Francisco, West Hollywood, and New York. They were calling their parents and brothers and sisters to say that they were dying. Yes, I have the “gay cancer.” Yes, I’m gay—and my “friend,” whom you have come to enjoy and love over the years, is my lover. And yes, he’s taking care of me. Except that he’s getting sick too. And dying, like me.

Men from little towns and hamlets all over America who had lived the “gay life” in secret, in faraway places, were calling home to say, “I’m sick with the gay disease.” And in countless homes all across America, mothers and fathers and siblings knew for the first time—or had their suspicions confirmed—that their son or brother was gay.

Lesbians were increasingly outed by the same experience. Having also moved to places of acceptance and affirmation in large cities, they had come to know their gay brothers who were now becoming sick. Many of them took care of their seriously ill gay friends. Many began to advocate for AIDS funding and treatment. Many sat with their gay friends and listened to the devastating fallout from coming-out to their parents. Many shared the pain of coming clean about who they were and whom they loved. And as a result, many of them felt called to come out to their own parents as lesbian—partly in solidarity with their gay brothers, and partly because they too wanted to live free from keeping secrets from the families they loved.

Increasingly, even those not infected with the virus that came to be known as HIV wanted this same freedom. Despite the terrible consequences of coming out experienced by many, there were enough success stories to make them wonder, “What if I came out to my parents? Would they still love me?” And so, in ever larger numbers, the calls or visits home began, for the purpose of coming out.

In countless living rooms across America, beloved sons and daughters sat down, hearts in their throats, to say, “Mom, Dad. I’m gay.” It is hard to describe the cataclysmic, earthquake-like effect this had on families. Something simply unthinkable had been revealed, although to be honest, many parents had wondered why their son or daughter hadn’t married, or didn’t even seem to be dating, or simply had become silent about his or her personal life. Now it all made sense—terrible and horrifying sense. Those whose sons were now sick with AIDS had a double whammy: they hardly knew which to grieve first, the revelation that they had a gay son or the fact that he was dying at age twenty-eight.

Remember how social change happens. Each of us has a worldview that pretty much interprets the world for us, puts our personal and public experiences in some kind of rational and understandable order. That worldview works fairly well for a period of time. Then something happens that renders it insufficient. Something happens that can’t be fit into life as we have known and interpreted it. Something so shocking and disturbing as to shake the very foundations of who we thought we were.

Parents across America knew they loved their sons. They were proud of them and bragged to relatives and friends about what they were accomplishing, albeit far away in San Francisco. They had learned not to ask too many personal questions, and there was often a feeling of something unspoken. But still, what a wonderful son he was!

And now this! Was he going to stay where he was, nursed by his “partner”? (What a strange new meaning to the word!) How could a parent explain to the neighbors these now-frequent trips to San Francisco, which clearly went beyond the annual visit? Or was he going to come home to die, to be cared for by his parents? And how could that be explained to nosy relatives—especially when they saw how emaciated he looked, with the telltale, dark reddish splotches of Kaposi’s Sarcoma beginning to appear on his face? The son’s coming-out to his parents often involved the parents’ coming-out to their family and friends—not a willing, voluntary coming-out as having a gay son, but one born of necessity and tragedy.

And so the parents were having an experience for which their comfortable worldview had not prepared them. They knew two things for sure: their son was gay, and they loved him. More often than not, this felt like being placed between a rock and a hard place. Being gay (what a strange word for a condition so tragic and so morally disgusting) was a terrible thing. But this was their son, whom they had always loved. And the family was thrown into emotional chaos, a battle between two competing truths. Over time, each family resolved this issue. For the unlucky ones, the gay son was disowned, pushed away, and condemned out of moral outrage and (usually) religious rigidity. For the lucky ones, the urge to love overcame the need to judge, and with tentative and uncertain steps these parents began to change their long-held worldview, to allow for the possibility that their child’s homosexuality might not be the end of the world, nor would it precipitate the end of their love for him.

In biblical imagery, the scales had fallen from their eyes. What was previously unknown or only suspected was confirmed. Now they knew. And so would everyone else. Parents would often experience an isolation of their own, fearing to tell friends and family the truth, lest they be blamed for their son’s homosexuality. After all, wasn’t it something they had done, or not done, that had made him this way? What would people think of them?

Simultaneous with the emergence of AIDS, and largely because of it, gay organizations took on a new courage and boldness. Groups like Act Up loudly proclaimed the presence of gay people: “We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it!” Those who resisted a vigorous response to the HIV/AIDS crisis, including gay men and lesbians who were unaffected by the pandemic, were challenged by “Silence = Death.” Harvey Milk, the first openly gay politician to be elected to public office in the previous decade, had said, “Coming-out is the most political thing you can do.” It turned out he was right. And as more and more gay men and lesbians came out to their families and friends—not because they had to, but because they wanted to—Americans realized that they knew someone gay or lesbian. And our world irrevocably changed.

In the years to come, other sexual minorities would be inspired to follow the lead of their gay brothers and lesbian sisters. People who were open to physical intimacy with people of either gender would come out as bisexual. And then we began to hear from people whose physical characteristics and genitals indicated one gender but whose feelings and inner being indicated the opposite. Transgender people are still in the early stages of coming-out, but because their very existence challenges our comfortable definitions of gender identity and expression (even for gay men and lesbians), it has been a difficult journey forward. The murder rate for open and honest transgender people is horrifyingly high. It is still a dangerous world for those who have come to know and acknowledge themselves as transgender. Transgender and bisexual people have joined their gay brothers and lesbian sisters in confronting their families with the truth about their lives.

High school and college reunions have often provided an opportunity for learning about people (not to mention humor!). It is very common for someone to show up at his or her reunion not with a spouse of the opposite gender but with a same-gender partner. This can come as a shock to a former classmate who only remembers you as the good-looking, girl-chasing captain of the football team. For some, it’s simply not on their radar screen. When Mark and I attended his reunion at Middlebury College and I was introduced to a friend as his “partner,” the clueless friend asked what business we were in.

Even more dramatic is the reunion where good ol’ Jack arrives back at his alma mater as Jacqueline, now a woman and looking pretty damn good! As the stigma against transgender people diminishes and more transgender people find the world safe enough to tell their stories, we will see more of this.

As much as some would like all this to have never occurred, or for the world to go back to a “simpler” time when “men were men, and women were women, and everyone knew the difference,” the fact is that toothpaste is never going back into the tube. This is a new reality, and like it or not, the world has to deal with it.

With this newly acknowledged existence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people in our midst—members of our families, next-door neighbors, former classmates, colleagues in the workplace, not to mention on TV and in the culture—a new awareness of the needs and aspirations of this group is emerging. With it, there is a growing understanding that this group has been discriminated against, not merely in a personal, individual way, but also in a societal structure that systematically rewards heterosexuals and punishes homosexuals, just as whites have been rewarded at the expense of blacks and men rewarded at the expense of women. Beyond the personal issue of whether kind and compassionate treatment will be accorded gay individuals, this systemic discrimination embedded in our societal norms, laws, and rights is a justice issue that begs for redress.

Increasingly, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people are demanding that they be treated with the same dignity and afforded the same responsibilities and rights as their heterosexual fellow citizens. Public policies are beginning to change. We’ve seen the end of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” in the military, and the White House has announced that it will no longer defend in court the so-called Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), believing it to be unconstitutional. There is even increased opposition to DOMA in Congress. Such systemic discrimination now seems antiquated and unfair to many. Challenges to state constitutional amendments barring gay marriage (and in some states, even the outlawing of civil unions and domestic partnerships between people of the same gender) are under way. While there is still opposition to changing these policies, it is now a foregone conclusion that these policies are worthy of a vigorous debate and that lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people may indeed have a legitimate and equal claim on the rights and privileges of citizenship in America.

In this context, the demand for marriage equality is not surprising. After all, marriage is the State’s way of promoting stability within society. Married couples are rewarded for their mutual commitments with tax benefits, insurance coverage, inheritance laws, and a host of other financial benefits. We are now living in a time of disconnect for many gay and lesbian couples who are legally married in their state of residence but still denied federal rights (including Social Security benefits and protections) because of the Defense of Marriage Act at the federal level.

But this debate isn’t just about financial advantage. It’s also about respect. Mutually committed couples of the same gender are increasingly demanding the societal and social respect that accrues from marriage—not just in America, but in many countries around the world. The burden is gradually but dramatically shifting from those who are arguing for equal treatment under the law to those who are having to explain why this equal treatment should not be the case. Perhaps no other shift in public opinion and public policy has occurred in such a short period of time, historically speaking. And we find ourselves talking about gay marriage in a way that would have been unimaginable only a few years ago. It is a conversation that is both particular (about rights, privileges, responsibilities, and benefits) and symbolic (about equal respect from the law and equal justice under the law). It is a conversation whose time has come.

Recenzii

“Personal, well-written, and well-argued . . . its greatest hope for success lies in soothing the troubled hearts of young people questioning their conflicting identities.”

—Louisville Courier-Journal

“An invitation to recognize the power and possibility of marriage for all people . . . Written with a pastoral heart and considerable academic insight, Robinson effectively argues the importance and value of strong marriages . . . a thoughtful theological approach.”

—SoWhatFaith.com

“A family-friendly, easy to read book that explains the necessity of gay marriage to the masses . . . courageous . . . erudite . . . conveys complicated principles with ease.”

—Edge

“Conversational and essayistic . . . methodically argued, cogently and brightly written, structured as chapter-length responses to commonly voiced questions about, and objections to, same-sex marriage . . . consistently Christian but also pervasively liberal.”

—The Boston Globe

“[A] mix of reasoned logic, personal experiences, church teachings, and social science . . . The underlying tone is one of compassion and genuine hope for meaningful shift toward acceptance of same-sex unions . . . gentle with moments of humor . . . a solid entrance into the LGBT-affirming worldview.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Reasoned . . . Robinson's strength is his willingness to see these questions from another perspective . . . Sober and well-structured.”

—Kirkus

“Couldn’t be more timely, nor more authoritative . . . Robinson does yeoman’s work at arguing [the gay-marriage debate] concisely.”

—Booklist

About Gene Robinson

“My friend, Bishop Gene Robinson, has long been a voice for equality—not with anger or vitriol, but with compassion and faith. He has been guided by the simple precept that we should do unto others as we would have them do unto us.”

—President Barack Obama

“For someone in the eye of the storm buffeting our beloved Anglican Communion, Gene Robinson is so serene; he is not a wild-eyed belligerent campaigner. I was so surprised at his generosity towards those who have denigrated him and worse. Gene Robinson is a wonderful human being, and I am proud to belong to the same church as he.”

—Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Nobel Peace Laureate

“Gene Robinson is no revolutionary: he upholds marriage as a sacred covenant, but knows the same covenant theology can include same-sex partnerships too. For living this truth he has been scapegoated—not for being the first gay bishop, but the first honest one. By God’s grace he had stayed strong, still trying to love his enemies into friends. One day the Church will understand what it owes him.”

—The Very Rev. Jeffrey John, Dean, St. Alban’s Cathedral, England

—Louisville Courier-Journal

“An invitation to recognize the power and possibility of marriage for all people . . . Written with a pastoral heart and considerable academic insight, Robinson effectively argues the importance and value of strong marriages . . . a thoughtful theological approach.”

—SoWhatFaith.com

“A family-friendly, easy to read book that explains the necessity of gay marriage to the masses . . . courageous . . . erudite . . . conveys complicated principles with ease.”

—Edge

“Conversational and essayistic . . . methodically argued, cogently and brightly written, structured as chapter-length responses to commonly voiced questions about, and objections to, same-sex marriage . . . consistently Christian but also pervasively liberal.”

—The Boston Globe

“[A] mix of reasoned logic, personal experiences, church teachings, and social science . . . The underlying tone is one of compassion and genuine hope for meaningful shift toward acceptance of same-sex unions . . . gentle with moments of humor . . . a solid entrance into the LGBT-affirming worldview.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Reasoned . . . Robinson's strength is his willingness to see these questions from another perspective . . . Sober and well-structured.”

—Kirkus

“Couldn’t be more timely, nor more authoritative . . . Robinson does yeoman’s work at arguing [the gay-marriage debate] concisely.”

—Booklist

About Gene Robinson

“My friend, Bishop Gene Robinson, has long been a voice for equality—not with anger or vitriol, but with compassion and faith. He has been guided by the simple precept that we should do unto others as we would have them do unto us.”

—President Barack Obama

“For someone in the eye of the storm buffeting our beloved Anglican Communion, Gene Robinson is so serene; he is not a wild-eyed belligerent campaigner. I was so surprised at his generosity towards those who have denigrated him and worse. Gene Robinson is a wonderful human being, and I am proud to belong to the same church as he.”

—Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Nobel Peace Laureate

“Gene Robinson is no revolutionary: he upholds marriage as a sacred covenant, but knows the same covenant theology can include same-sex partnerships too. For living this truth he has been scapegoated—not for being the first gay bishop, but the first honest one. By God’s grace he had stayed strong, still trying to love his enemies into friends. One day the Church will understand what it owes him.”

—The Very Rev. Jeffrey John, Dean, St. Alban’s Cathedral, England