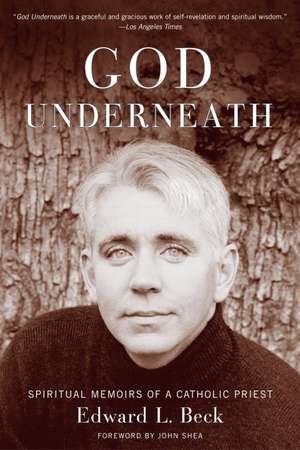

God Underneath: Spiritual Memoirs of a Catholic Priest

Autor Edward L. Beck John Sheaen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 iun 2002

Father Edward L. Beck spins tales like a master, presenting with candor and a touch of irreverence incidents and events that will resonate with readers. Exploring such universal themes and concerns as friendship, sexuality, illness, alcoholism, loss, and death, the vignettes and stories in this collection are animated by intriguing characters, pitch-perfect dialogue–and a surprising twist. Probing beneath the surface of ordinary life, each selection contains a hidden message, a subtle but powerful reminder of the signposts that mark a spiritual journey.

Quotations from the Scriptures introduce the tales, providing a context that will help readers uncover the meaning the story holds for their own personal lives and beliefs. To encourage further reflection and rumination, Beck offers insights into the specific religious and theological themes that inspired the writing of each tale.

A lively, unabashed look at the challenges of living a spiritual life in contemporary times, God Underneath will appeal not only to Catholics, but to all spiritual seekers, regardless of religious affiliation.

Preț: 99.30 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 149

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.00€ • 19.93$ • 15.82£

19.00€ • 19.93$ • 15.82£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 11-25 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385501811

ISBN-10: 0385501811

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: IMAGE

ISBN-10: 0385501811

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 140 x 208 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: IMAGE

Notă biografică

EDWARD L. BECK, C.P., is a Roman Catholic priest and a member of the Passionist community. A onetime parish priest, director of seminarians, and campus minister, he travels throughout the country preaching and organizing retreats and workshops. He has experience in theater, radio, and television. He lives in New York City.

Extras

CHAPTER ONE

NAME RECOGNITION

See, upon the palms of my hands I have written your name.

--Isaiah 49:16

I was supposed to be named Adelaide . . . if I was born a girl. My mother gives thanks to this day that the first thing she saw while lying on the delivery table was a penis. The doctor held me up all bloody, squirming, and screaming and moved to lay me on my mother's chest.

My mother winced and said, "Oh, thank God, a boy. But, please, clean him up first." She is still saying that in one way or another. Who could have predicted the lasting power of that first breath metaphor?

My parents married young--three times, each time to one another, and with no divorces. That must be a record somewhere. The first wedding occurred after an evening of revelry spent with friends at Frankie and Johnny's pub in Flatbush, Brooklyn. The magic of that evening and the lowering of inhibitions provided by enough beer and whiskey sours made an expeditious marriage seem inviting. My parents hopped into a 1955 Chevy Impala and headed toward the Mason-Dixon line. My mother called her mother from Maryland (a state known to marry you within twenty-four hours, no questions asked) to tell her where she was and what she was planning.

"Momma, I'm in Maryland with Eddie and we're going to get married."

"Well, I figured that was coming sooner or later. He's a good guy and he seems to treat you well. It's just too bad he doesn't have money. You know love goes out the window when the bills come in the door."

"Oh, Momma!"

"You can learn to love anyone who treats you well, but you love them even more when they have money and can treat you really well."

"Momma, we'll be fine, and I do love him--money or no money."

"O.K., but don't you come home here unless you two get married. If you stay out all night with a man, you had better be married to him."

"Momma, we are getting married. That's why I called you. I'll see you sometime tomorrow."

Once the inspiring phone call had ended, my mother anxiously sought out a priest, because she wanted to be married in the Church. Religious affiliation was not yet paramount for my father. A justice of the peace would do just fine for him. But late in her teens my mother had discovered her Catholicism anew and she fell for it mightily, making novenas three times a week and never missing Mass. It was important to her that the Church from which she received so much solace and meaning bless this marriage.

They finally found a priest willing to sit down with them after ringing the doorbells of a few rectories. The seasoned cleric listened patiently to this young woman's story, touched by her desire to make this marriage sacramental, but not touched enough.

"Are you pregnant?" he asked her.

"No, no, of course not," she said.

"Then go home and forget about this nonsense. It will never last. Take your time; plan a proper wedding. Do this right. It's too important to rush through on a whim."

But my mother knew they couldn't go home. It was too late. It was already well into the night and Nanny's words echoed in her mind--she had better be married to him.

Left with no other alternative, my parents sought out a justice of the peace, who performed a no-frills nuptial in a private chamber with people they met that night serving as witnesses. Geraldine, a twenty-year-old red-haired knockout with a dazzling smile, and Eddie, a twenty-two-year-old blue-eyed charmer with a gelled pompadour, exchanged rings and promised forever. The obviously overworked justice flatly said words he probably uttered in his sleep, "I now pronounce you man and wife." The newlyweds spent their first night in a prosaic Maryland hotel which offered them congratulatory free beer as a toast to their legal but not yet sacramental bond.

During the drive home, my mother began to consider the priest's question: "Are you pregnant?"

"He had some nerve asking me that. Is that the only reason people elope? It did get me to thinking though about when we do finally have a child. What will we name it?"

"Gerri," my father said, "that's quite a ways off. Do we really need to talk about it now?"

"Well, I mean just for fun. I already know anyway. If we have a son, I want to name him Christopher Michael after my stepfather and real father, and if it's a girl, I think, Maureen, a nice Irish name."

"Fine, whatever," my father said, more intent on worrying about where they were going to live.

Once they had secured a modest apartment and had gotten settled with the details of newly married life, the call of the sacrament returned with an insistent beckoning. My mother still earnestly wanted to be married in the Church, and my father had gradually become convinced of its value. My parents went to see another priest. After listening sympathetically to their Maryland odyssey, this priest finally agreed to marry them.

"You know, of course, that this is a serious sacramental commitment," he said to them in hushed tones. "You must invite God into this union if it is to perdure. And you must work at it. I'll do this wedding, but you are the ones that will have to make it last."

They accepted the priest's counsel, ready to agree with whatever he said, and were elated that someone was finally willing to marry them. A small wedding was planned. My parents felt some embarrassment at having to repeat the nuptials, but they trusted that this time would be qualitatively different. With family and friends gathered, pungent lilacs placed at the high altar and in front of the Mary statue, and the organ playing a melodious Bach cantata, the priest leaned over to my father, who had on a flattering charcoal gray suit, and requested the marriage license. My father looked at my mother in her beige, lace-sleeved dress. She turned and looked at her red-haired sister, who didn't know to whom to look. Then everyone looked horrified. No one had realized my parents would need a New York State marriage license and blood test after having already been married in Maryland. The wedding was off. With sacramental connubial bliss evading my parents once more, the disgruntled guests retired to a local bar to await word of the next ceremony.

After attending to the New York legalities, some weeks later my parents returned to the church and were married in an unceremonious wedding, witnessed by only my aunt and grandfather and a few friends at a side altar in St. Edmund's Church in Brooklyn. Others who had attended the first aborted Church wedding passed on this one, sure that another mishap would dictate a further delay. They had better things to do with their Saturday afternoons. With New York State license and blood test in hand, the young couple said, "I do," again, this time before God; thus making the legal bond a sacramental one as well. With God finally giving His stamp of approval, my parents were determined to live up to their end of the bargain.

For years this escapade has remained a running joke in my family, especially at the time of my parents' anniversary each year. "Now, which one are we celebrating anyway?" My mother is not amused.

Oh, yes, but about my name. It all came down to money. My parents struggled financially in the early years of their marriage. My mother had heeded Nanny's advice in marrying a man who treated her well, but unfortunately not one who had money. My father worked three jobs at one time to keep them afloat, including driving a taxi in New York City, which in itself merits praise and extra life insurance. When not bartending at Monahan's, he would do odd handyman jobs, like fixing leaking sinks or helping to remodel outdated kitchens that no longer satisfied Flatbush housewives. He was dexterous with a hammer and screwdriver, prompting people to remark how lucky my mother was to have a husband who could do things around the house.

But about the name. I learned late in life that I wasn't my parents' first child. They had endured a miscarriage a few months after their marriage. In addition to the obvious sadness, this also put them in a delicate position. Because the pregnancy was interrupted, no one was able to accurately chart the date of conception. My mother got wind that some were concluding that she and my father "had to get married."

"They have some nerve," she said to my father. "They should only know that I wouldn't even let you kiss me the wrong way because the priest told me it was a sin."

My mother took a protective stance toward the next pregnancy, the one that ultimately resulted in my being born. She maintains that she hardly went out of the house for the nine months for fear of miscarrying again. She ate a lot of Breyer's ice cream and Nathan's hot dogs, watched Lucy and Desi on TV (Lucy was also pregnant), and ballooned to 175 pounds from a svelte 135 pounds. Liver spots covered her face and the red hair dye she used wouldn't take. She says it wasn't pretty.

Because of my parents' limited resources, the costs of having a child so soon proved daunting. Perceiving my imminent arrival, Grandpa Beck saw an opportunity. An overweight man with a chin that doubled down to his chest, he was a dinner guest most Sundays. He was also a wonderful cook, holding culinary secrets to savory German meals, secrets he often shared with my mother, if she agreed to execute the meal as he directed. He was a tough tutor, though, always correcting, subtly putting down even her most earnest of efforts. He also had trouble with gambling, losing large amounts of money at the racetrack, including my father's share of a taxi business they owned together--something my father won't talk about to this day.

"Well," Grandpa Beck said one day as he lowered himself onto the sofa in the living room for the beginning of a TV ball game. "I know you two are kind of strapped financially and you have a baby on the way, so I'd be willing to help out. I'll buy you a beautiful baby carriage, so it's one less thing you'll have to worry about."

"Gee, that's very nice of you, Pop," my father said. "Thank you. We appreciate it."

"There's just one thing," my grandfather continued. "I'd like to be able to name the baby in exchange for me getting you the carriage."

"Name the baby?" my mother said warily. "What would you name it?"

He said, "Well, if it's a girl, I'd like to name her after my deceased wife, Eddie's mother, Adelaide."

My mother choked on her rye and club soda and dropped her handful of peanuts back into the dish. "Adelaide?"

"And if it's a boy, I'd like to name him Edward Leon Beck III. We may as well continue my and your husband's name. It has served us well all these years."

My mother was able to swallow her drink on this one, but barely. She saw her dreams of Christopher Michael and Maureen being dashed more quickly than my father could mix another drink. She also resented being bribed, but she needed a carriage. "After all," she reasoned, "this probably wouldn't be their only child." The names would still be there. She could live with Edward III; at least it had a regal quality to it. She didn't know, however, if she could forgive herself if forced to name a daughter Adelaide, who she was sure would be called "Addy" for short. The mere thought of it gave her stomach cramps well before the onslaught of labor. But having little choice, she entered into this Mephistophelean agreement, albeit reluctantly, with the hopes that Adelaide would never be a name she'd have to put on a birth certificate. So, that day in the delivery room, as she prayed up a storm and held her medal of Saint Gerard close to her chest, she was never so happy to see a penis.

I have always preferred Edward to Ed or Eddie, partly because my grandfather was Ed and my father, Eddie. I wanted my own version. I like the sound of my name being called, probably because it signals that the one calling has some connection with me. As a child, I could tell the caller's emotion by the mere intonation used. The "Edward!" screamed by my mother when I had inadvertently crayoned the living room wall as a child sounded like a different language from the "Edward" cooed when I brought home a self-made Mother's Day card complete with kisses and hugs. Of course, this is a universal experience. The name uttering you might welcome in moments of unselfconscious lovemaking is worlds apart from the name sputtering you surely dread when it is discovered that you mistakenly left the water running in the bathtub, ruining the freshly painted ceiling of the den below. Whole sentences are spoken in one word, the name.

There is also power in a name. When someone calls me Edward, as opposed to the various derivatives, I know that person has a part of me not everyone does, however small it may seem. They know me well enough to be familiar, and to respect my preference. This is the reason ancient Israel never said or wrote the name of God. They believed that to say or write the name gave one power over the Deity. It was too familiar. Ancient Israel presumed no such power. When needing to refer to God, YHWH was written, which cannot be uttered without the vowels that render YAHWEH. Today one often sees G-d, also unspeakable.

The Scriptures do, however, refer to a God who calls us by name, sometimes suggesting a lover whose hands are all over us. The God who has written our names on the palm of God's hands (Isaiah 49:16) is the One of whom the psalmist sings, "Truly you have formed my inmost being; you knit me in my mother's womb" (Psalm 139:13).

From the moment I was conceived, I am confident God has been whispering, "Edward," beckoning me forth into a fullness of life that only God can ultimately provide. God calls me by name because God knows me that intimately, the most intimately anyone can know me. And when God speaks my name, it is always as lover--never as angry parent or disgruntled spouse. God makes rainbows out of the crayoned wall and waterfalls out of the overflowing tub.

NAME RECOGNITION

See, upon the palms of my hands I have written your name.

--Isaiah 49:16

I was supposed to be named Adelaide . . . if I was born a girl. My mother gives thanks to this day that the first thing she saw while lying on the delivery table was a penis. The doctor held me up all bloody, squirming, and screaming and moved to lay me on my mother's chest.

My mother winced and said, "Oh, thank God, a boy. But, please, clean him up first." She is still saying that in one way or another. Who could have predicted the lasting power of that first breath metaphor?

My parents married young--three times, each time to one another, and with no divorces. That must be a record somewhere. The first wedding occurred after an evening of revelry spent with friends at Frankie and Johnny's pub in Flatbush, Brooklyn. The magic of that evening and the lowering of inhibitions provided by enough beer and whiskey sours made an expeditious marriage seem inviting. My parents hopped into a 1955 Chevy Impala and headed toward the Mason-Dixon line. My mother called her mother from Maryland (a state known to marry you within twenty-four hours, no questions asked) to tell her where she was and what she was planning.

"Momma, I'm in Maryland with Eddie and we're going to get married."

"Well, I figured that was coming sooner or later. He's a good guy and he seems to treat you well. It's just too bad he doesn't have money. You know love goes out the window when the bills come in the door."

"Oh, Momma!"

"You can learn to love anyone who treats you well, but you love them even more when they have money and can treat you really well."

"Momma, we'll be fine, and I do love him--money or no money."

"O.K., but don't you come home here unless you two get married. If you stay out all night with a man, you had better be married to him."

"Momma, we are getting married. That's why I called you. I'll see you sometime tomorrow."

Once the inspiring phone call had ended, my mother anxiously sought out a priest, because she wanted to be married in the Church. Religious affiliation was not yet paramount for my father. A justice of the peace would do just fine for him. But late in her teens my mother had discovered her Catholicism anew and she fell for it mightily, making novenas three times a week and never missing Mass. It was important to her that the Church from which she received so much solace and meaning bless this marriage.

They finally found a priest willing to sit down with them after ringing the doorbells of a few rectories. The seasoned cleric listened patiently to this young woman's story, touched by her desire to make this marriage sacramental, but not touched enough.

"Are you pregnant?" he asked her.

"No, no, of course not," she said.

"Then go home and forget about this nonsense. It will never last. Take your time; plan a proper wedding. Do this right. It's too important to rush through on a whim."

But my mother knew they couldn't go home. It was too late. It was already well into the night and Nanny's words echoed in her mind--she had better be married to him.

Left with no other alternative, my parents sought out a justice of the peace, who performed a no-frills nuptial in a private chamber with people they met that night serving as witnesses. Geraldine, a twenty-year-old red-haired knockout with a dazzling smile, and Eddie, a twenty-two-year-old blue-eyed charmer with a gelled pompadour, exchanged rings and promised forever. The obviously overworked justice flatly said words he probably uttered in his sleep, "I now pronounce you man and wife." The newlyweds spent their first night in a prosaic Maryland hotel which offered them congratulatory free beer as a toast to their legal but not yet sacramental bond.

During the drive home, my mother began to consider the priest's question: "Are you pregnant?"

"He had some nerve asking me that. Is that the only reason people elope? It did get me to thinking though about when we do finally have a child. What will we name it?"

"Gerri," my father said, "that's quite a ways off. Do we really need to talk about it now?"

"Well, I mean just for fun. I already know anyway. If we have a son, I want to name him Christopher Michael after my stepfather and real father, and if it's a girl, I think, Maureen, a nice Irish name."

"Fine, whatever," my father said, more intent on worrying about where they were going to live.

Once they had secured a modest apartment and had gotten settled with the details of newly married life, the call of the sacrament returned with an insistent beckoning. My mother still earnestly wanted to be married in the Church, and my father had gradually become convinced of its value. My parents went to see another priest. After listening sympathetically to their Maryland odyssey, this priest finally agreed to marry them.

"You know, of course, that this is a serious sacramental commitment," he said to them in hushed tones. "You must invite God into this union if it is to perdure. And you must work at it. I'll do this wedding, but you are the ones that will have to make it last."

They accepted the priest's counsel, ready to agree with whatever he said, and were elated that someone was finally willing to marry them. A small wedding was planned. My parents felt some embarrassment at having to repeat the nuptials, but they trusted that this time would be qualitatively different. With family and friends gathered, pungent lilacs placed at the high altar and in front of the Mary statue, and the organ playing a melodious Bach cantata, the priest leaned over to my father, who had on a flattering charcoal gray suit, and requested the marriage license. My father looked at my mother in her beige, lace-sleeved dress. She turned and looked at her red-haired sister, who didn't know to whom to look. Then everyone looked horrified. No one had realized my parents would need a New York State marriage license and blood test after having already been married in Maryland. The wedding was off. With sacramental connubial bliss evading my parents once more, the disgruntled guests retired to a local bar to await word of the next ceremony.

After attending to the New York legalities, some weeks later my parents returned to the church and were married in an unceremonious wedding, witnessed by only my aunt and grandfather and a few friends at a side altar in St. Edmund's Church in Brooklyn. Others who had attended the first aborted Church wedding passed on this one, sure that another mishap would dictate a further delay. They had better things to do with their Saturday afternoons. With New York State license and blood test in hand, the young couple said, "I do," again, this time before God; thus making the legal bond a sacramental one as well. With God finally giving His stamp of approval, my parents were determined to live up to their end of the bargain.

For years this escapade has remained a running joke in my family, especially at the time of my parents' anniversary each year. "Now, which one are we celebrating anyway?" My mother is not amused.

Oh, yes, but about my name. It all came down to money. My parents struggled financially in the early years of their marriage. My mother had heeded Nanny's advice in marrying a man who treated her well, but unfortunately not one who had money. My father worked three jobs at one time to keep them afloat, including driving a taxi in New York City, which in itself merits praise and extra life insurance. When not bartending at Monahan's, he would do odd handyman jobs, like fixing leaking sinks or helping to remodel outdated kitchens that no longer satisfied Flatbush housewives. He was dexterous with a hammer and screwdriver, prompting people to remark how lucky my mother was to have a husband who could do things around the house.

But about the name. I learned late in life that I wasn't my parents' first child. They had endured a miscarriage a few months after their marriage. In addition to the obvious sadness, this also put them in a delicate position. Because the pregnancy was interrupted, no one was able to accurately chart the date of conception. My mother got wind that some were concluding that she and my father "had to get married."

"They have some nerve," she said to my father. "They should only know that I wouldn't even let you kiss me the wrong way because the priest told me it was a sin."

My mother took a protective stance toward the next pregnancy, the one that ultimately resulted in my being born. She maintains that she hardly went out of the house for the nine months for fear of miscarrying again. She ate a lot of Breyer's ice cream and Nathan's hot dogs, watched Lucy and Desi on TV (Lucy was also pregnant), and ballooned to 175 pounds from a svelte 135 pounds. Liver spots covered her face and the red hair dye she used wouldn't take. She says it wasn't pretty.

Because of my parents' limited resources, the costs of having a child so soon proved daunting. Perceiving my imminent arrival, Grandpa Beck saw an opportunity. An overweight man with a chin that doubled down to his chest, he was a dinner guest most Sundays. He was also a wonderful cook, holding culinary secrets to savory German meals, secrets he often shared with my mother, if she agreed to execute the meal as he directed. He was a tough tutor, though, always correcting, subtly putting down even her most earnest of efforts. He also had trouble with gambling, losing large amounts of money at the racetrack, including my father's share of a taxi business they owned together--something my father won't talk about to this day.

"Well," Grandpa Beck said one day as he lowered himself onto the sofa in the living room for the beginning of a TV ball game. "I know you two are kind of strapped financially and you have a baby on the way, so I'd be willing to help out. I'll buy you a beautiful baby carriage, so it's one less thing you'll have to worry about."

"Gee, that's very nice of you, Pop," my father said. "Thank you. We appreciate it."

"There's just one thing," my grandfather continued. "I'd like to be able to name the baby in exchange for me getting you the carriage."

"Name the baby?" my mother said warily. "What would you name it?"

He said, "Well, if it's a girl, I'd like to name her after my deceased wife, Eddie's mother, Adelaide."

My mother choked on her rye and club soda and dropped her handful of peanuts back into the dish. "Adelaide?"

"And if it's a boy, I'd like to name him Edward Leon Beck III. We may as well continue my and your husband's name. It has served us well all these years."

My mother was able to swallow her drink on this one, but barely. She saw her dreams of Christopher Michael and Maureen being dashed more quickly than my father could mix another drink. She also resented being bribed, but she needed a carriage. "After all," she reasoned, "this probably wouldn't be their only child." The names would still be there. She could live with Edward III; at least it had a regal quality to it. She didn't know, however, if she could forgive herself if forced to name a daughter Adelaide, who she was sure would be called "Addy" for short. The mere thought of it gave her stomach cramps well before the onslaught of labor. But having little choice, she entered into this Mephistophelean agreement, albeit reluctantly, with the hopes that Adelaide would never be a name she'd have to put on a birth certificate. So, that day in the delivery room, as she prayed up a storm and held her medal of Saint Gerard close to her chest, she was never so happy to see a penis.

I have always preferred Edward to Ed or Eddie, partly because my grandfather was Ed and my father, Eddie. I wanted my own version. I like the sound of my name being called, probably because it signals that the one calling has some connection with me. As a child, I could tell the caller's emotion by the mere intonation used. The "Edward!" screamed by my mother when I had inadvertently crayoned the living room wall as a child sounded like a different language from the "Edward" cooed when I brought home a self-made Mother's Day card complete with kisses and hugs. Of course, this is a universal experience. The name uttering you might welcome in moments of unselfconscious lovemaking is worlds apart from the name sputtering you surely dread when it is discovered that you mistakenly left the water running in the bathtub, ruining the freshly painted ceiling of the den below. Whole sentences are spoken in one word, the name.

There is also power in a name. When someone calls me Edward, as opposed to the various derivatives, I know that person has a part of me not everyone does, however small it may seem. They know me well enough to be familiar, and to respect my preference. This is the reason ancient Israel never said or wrote the name of God. They believed that to say or write the name gave one power over the Deity. It was too familiar. Ancient Israel presumed no such power. When needing to refer to God, YHWH was written, which cannot be uttered without the vowels that render YAHWEH. Today one often sees G-d, also unspeakable.

The Scriptures do, however, refer to a God who calls us by name, sometimes suggesting a lover whose hands are all over us. The God who has written our names on the palm of God's hands (Isaiah 49:16) is the One of whom the psalmist sings, "Truly you have formed my inmost being; you knit me in my mother's womb" (Psalm 139:13).

From the moment I was conceived, I am confident God has been whispering, "Edward," beckoning me forth into a fullness of life that only God can ultimately provide. God calls me by name because God knows me that intimately, the most intimately anyone can know me. And when God speaks my name, it is always as lover--never as angry parent or disgruntled spouse. God makes rainbows out of the crayoned wall and waterfalls out of the overflowing tub.

Recenzii

The very first time I saw Father Edward’s face, I knew I would learn something about ‘men of the cloth’. A little the way you come to realize that your most erudite teachers have nightmares and hurt feelings and stomach aches. I had always been a little too much in awe of Priests, monks and other clergy or theological types. Maybe this is because they have to keep a distance in order to have you (the hopeful believer) believe they are a link to the great unknown. Edward Beck allows us close enough to see the emotions of a man. Because of the flawed humanity revealed, there is more reason to see that link. It will mean something special to the reader to see the courage that enables him to reveal himself so simply and honestly. To identify with him: to empathize, to feel his doubts , and then his overriding desire to go beyond and through them, is what his journey is about.

-Carly Simon

-Carly Simon

Descriere

A delightfully different approach to religion and spirituality, this collection of engaging personal tales--available now in paperback--transcends specific doctrines to reveal the presence of God in everyday life.