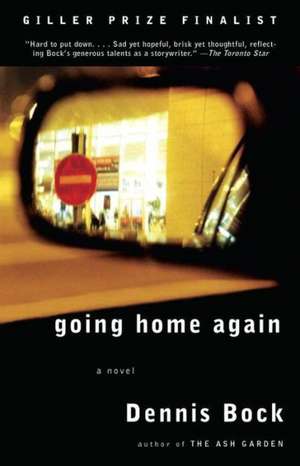

Going Home Again

Autor DENNIS BOCKen Limba Engleză Paperback – 5 mai 2014

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

Scotiabank Giller Prize (2013)

Charlie Bellerose leads a seminomadic existence, traveling widely to manage the language academies he has established in different countries. After separating, somewhat amicably, from his wife, he moves from Madrid back to his native Canada to set up a new school, and for the first time he forges a meaningful relationship with his brother, who’s going through a vicious divorce. Charlie’s able to make a fresh start in Toronto but longs for his twelve-year-old daughter, whom he sees only via Skype and the occasional overseas visit. After a chance encounter with a girlfriend from his university days, a woman now happily married and with children of her own, he works through a series of memories-including a particularly painful one they share-as he reflects on questions of family, home, fatherhood, and love. But two tragic events (one long past, the other very much in the present) finally threaten to destroy everything he's ever believed in.

Preț: 86.98 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 130

Preț estimativ în valută:

16.64€ • 17.17$ • 13.89£

16.64€ • 17.17$ • 13.89£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781400096107

ISBN-10: 1400096103

Pagini: 257

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 1400096103

Pagini: 257

Dimensiuni: 130 x 201 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: VINTAGE BOOKS

Notă biografică

Dennis Bock was awarded the Canada-Japan Literary Award in 2002 for The Ash Garden. He lives in Toronto.

Extras

Chapter One

There was no reason to think anything would be different between me and my brother the previous summer, in 2005, when I called ahead to tell him I was coming back to Toronto to try out my new life as a single man. I’d been studying the possibility of taking the business across the Atlantic for years, but for too many reasons to count, I’d never managed to pull it off. After finding out about the Supreme Court justice named Pablo, though, and having by then bunkered down at the Reina Victoria Hotel for two months, I was feeling sufficiently unsettled to actually do it. I needed some changes in my life. New schedule, new people, new rhythms. I was hoping for something else but wasn’t at all sure what it might be. The challenge of setting up my fifth language academy was a project that would focus my energies in the meantime and perhaps turn off the panicked voice in my head that kept telling me things I didn’t want to hear.

I wondered if some overlooked germ of hope had lain dormant in my heart over the years since I’d last seen my brother. But it wasn’t an easy telephone call to make at the time. There had always been some fundamental confusion between us, a wall, in effect an unending failure to imagine how the other saw and thought about the world that too often made things go sideways between us. That’s what had happened in Madrid the last time I’d seen him. We’d spoken by phone half a dozen times since then—on a birthday, his or mine, or the shared anniversary of our parents’ deaths—and I’d always come away glad to know he was well but also relieved that our lives were separate and distinct and that the problems between us might remain buried to the end of our days.

They had met only once, Isabel and Nate, when he came through Madrid back in 1992, the summer of the Barcelona Olympics and the Seville World’s Fair, after dumping the girl he was traveling with in France. He turned up at our door one night and told us he was heading down to check out the señoritas in Seville, then going back north to try to score some tickets for the sailing competitions in Catalonia. We put him up on the couch for a week. Showing him around my adopted hometown, I took him to the oldest restaurant in the world and spent a wad of money I didn’t really have. We wandered through neighborhoods packed with bars and clubs. Nothing seemed to impress him. In fact he found it all just a little bit irritating. The city was too hot and dirty and loud; he bitched and moaned about train schedules and shitty restaurants and the near-complete absence of spoken English in the streets and hotels. I got the impression that every- thing he saw in Spain made him feel superior, though of course he didn’t say as much. His last night with us he got stupidly drunk and said he wanted to go find some prostitutes. At first it was a joke I could almost brush aside. But he kept insisting. Then he draped his arm around Isabel’s neck and asked if out of the good- ness of her heart she could possibly loosen that grip she’d fastened around my balls, the boys just wanted to go out and have some fun for a change. That’s when I took him out for a drink he didn’t need and told him he could find some other couch to sleep on. I knew he had some experience with prostitutes. I didn’t care so much about that, since we both did. What I couldn’t stand was him treating Isabel as if she were some sort of obstacle in my life. The whole week had been building up to that moment. He’d been throwing out little put-downs and challenges, testing to see how far he could push me. When I told him what a selfish prick I thought he was, he took a swing at me right there in front of the bar. Not nearly as drunk as he was, I just stepped aside, went back to the apartment and took Isabel out to dinner. His backpack was gone when we got home a few hours later. The taps in the kitchen and bathroom were open full blast and a jug of water had been emptied into our bed. It was probably three or four years before I talked to him again.

So I was surprised, maybe even a little suspicious, I’ll admit now, when he offered to pick me up at the air- port. What might have changed, I wondered. A few hours into my flight I became convinced it had to be a misunderstanding and doubted he’d show. At baggage collection I watched an empty baby bassinet make three solitary revolutions and weighed my immediate prospects. I had a pocketful of euro coins that weren’t going to do me a lick of good here, a cell phone with thirty-seven Madrid numbers on speed dial and one single solitary local address written out on an old Post- it in my wallet. For an uncomfortable moment I felt something like a college student on the first leg of the big trip, tired, woefully underprepared and full of conflicting emotion. I saw my brother for an instant then—he was standing in the concourse—when the automatic doors that separated us opened. I almost didn’t recognize him, not because he’d changed—he hadn’t—but for the simple shock of seeing him there.

He was holding a newspaper in his right hand and wearing jeans and a green golf shirt. I might have smiled when I saw him—surprised he’d actually come to meet me—and then I wondered if he somehow knew I was limping home at the end of my marriage. Would he remind me, after thirteen years apart, that he’d always come out on top in the competition that seemed to rule us? Steeling myself, I collected my luggage and continued to the doors. He saw me and waved, and when we embraced, I recognized the cologne that our father had worn when we were boys. I didn’t know what it was called, but its scent opened my eyes like an old family photograph.

“My big little brother,” he said. “Welcome home.”

“It’s good to see you, Nate,” I said.

I’m taller than my brother by two fingers, have been since I caught up and passed him at the age of fourteen, and when we stood back from our embrace, he put his hand on my shoulder—the railing still separated us at hip level—and nodded and smiled as if some pleasant observation was registering in his mind. His hair was thick and dark, gelled or greased and cut short in a way that made him look younger than his years. He looked more or less as I remembered him. He was a fit and handsome man, like our father, with strong shoulders and a natural athletic grace that had favored him throughout and beyond his high school years. I couldn’t begin to imagine how much my appearance had changed since then. I had expected a similar aging in my brother, of course, the beginnings of a paunch or the thinning of hair that followed on our father’s side. But there was no hint of that. The years seemed to have passed him by. His face was still unlined and youthful-looking, his dark hair was thick as ever, and he wore the same conspiratorial and dazzling smile he’d used to his advantage when we were kids.

There were no awkward silences between us that day. As he drove me into the city—we were riding in air-conditioned comfort in a big white Escalade that afforded us a bird’s-eye view of the laps of the drivers in the next lane—he mentioned his kids three or four times, how great they were, what they did for fun, how he liked nothing more than hanging out in the back- yard and grilling hot dogs and burgers for them. Sticking to the upside of my life, I told him that Ava was an athletic and popular kid, almost twelve years old at that point, a kid who loved to read, did great in school and had a knack for languages. “Can you believe it? Us as dads,” he said. “The mind boggles.”

A few minutes later he pointed out an office tower in the distance, tall and glassy and shimmering in the afternoon sunshine, sixty stories of gold-tinted windows. He was a partner with one of the big law firms in that building, specializing in sports and entertainment. His client list had a number of golf and baseball and hockey players on it. The only name that stood out for me was a young female tennis player’s, likely because I’d always kept an eye on that game for its connection to memories of summer evenings spent rallying tennis balls against the south wall of my high school. Cycling, tennis and swimming had been my areas of concentration, solitary sports whose lack of bullish camaraderie seemed to make him suspicious at the time.

“Sounds like you enjoy what you do,” I said.

“There aren’t a lot of guys around these days who can make that claim.”

“I’m not saying life’s perfect where I’m sitting. I’ve got a bit of a domestic situation going on.”

“Oh?”

He told me that Monica—his sons’ mother—had moved out in April, three days after tossing her wedding band into the Toronto harbor at the end of a night on the town with three girlfriends. Now she was living with an older Swedish man who owned what he described as a multidimensional sports-and-entertainment complex for the modern adventure-seeking kid, a high- end, one-stop birthday emporium called Wonderworld. The man in question had come over from Scandinavia in the early nineties and doggedly built a chain of these franchises across the country.

“That’s where she met the guy. At our kid’s tenth birthday party. Nice, eh?”

“I’m sorry to hear it,” I said.

Since then Nate and Monica had hashed out an agreement where the kids were concerned. Everything else was still up in the air. Technically he took his sons every other week, but now he was traveling so much and so often that he was barely able to keep up his end of the deal. His tone when he told me this wasn’t whiny or bitter, not on that first afternoon, anyway. If anything he seemed contemplative—a word I never expected to use to describe my brother. But that’s how he came off that day as he drove me into the city. It seemed he’d been humbled. It stood to reason. You can’t go through something like that and not be.

I listened to the rest of his story, then told him something of my own great humbling. The two stories were dishearteningly similar.

He nodded in agreement. “Yeah,” he said, “that sounds just about right. Bang, bang, bang. Half the marriages on our street have gone bust. It’s a freaking epidemic here. Maybe it’s different in those Catholic countries. But here . . .” He shook his head again, then smiled.

“What?”

“You know those little fridge magnets? The ones with writing on them? Some little bead of wisdom or saying or whatever to warm your day.”

“Sure. I think so.”

“We had one on our fridge forever. I didn’t think much about it. I thought it was just a joke. It used to give me a laugh.”

“What did it say?”

“‘Men are like floors. If you lay them right the first time, you can walk all over them for years.’ ” He smiled a big genuine smile.

“Who’s going to argue with that, right?” I said.

“But that was her basic philosophy. Typical passive- aggressive bullshit that women get away with all the time now. Maybe it’s different over in Spain, who knows? But a guy puts some sexist joke about women on his fridge here, he’s automatically a misogynist and creepy asshole. Stay long enough, you’ll see for yourself.”

Nate lived in the city’s east end, two blocks north of the old Don Jail, in a nice-looking neighborhood set at the edge of a deep, wide valley. When he led me through his house that afternoon he told me it had been featured in House & Home and Architectural Digest; he managed to impart this information without seeming to brag, though of course that’s exactly what he was doing. He directed my attention to an oversize book on the coffee table called Rustic Cottage Ontario, and when he flipped it open to a photograph showing the vacation property he’d recently bought two hours north of the city, I told him it looked like things were going well for him.

And it was true. The walls in the room he’d led me into were hung with colorful paintings, and the hardwood floors were covered in fine rugs. The overall feel of the place was original, homey and expensive. It seemed he’d made himself into a success. But I hadn’t intended the comment to be understood this way, if in fact it had been. I’d meant to say that he’d taken his life in a positive direction, or so it appeared, given what the details seemed to suggest. Despite the domestic situation he’d referred to, my brother had ended up a family man, or at least some version of one. I saw the traces everywhere: a golf putter, a base- ball glove, a heavily thumbed copy of the latest Harry Potter; playing cards were scattered over the dining room table; a Monopoly set was open midgame on the coffee table beside the cottage book. Someone had left a skateboard in the middle of the living room floor, and rather than cursing and stepping over it as we moved into the kitchen he lowered his foot decisively against its stern, and the board obediently popped up into his hand, and he tucked it under his arm with a smile. It was a trick he might have per- formed in the family driveway thirty-five years before. And that’s when I wondered for the first time if my brother had truly changed. Had I judged him too harshly? Had I even remembered him correctly after all those years?

Two cats appeared from behind a couch, one black, one white, and disappeared up the carpeted stairs. He leaned the skateboard against the wall, its wheels still spinning noiselessly, and grabbed two bottles of Heineken from the fridge. We stepped out into the backyard. Overhead was the sort of sky that seems to go on forever. There was nothing but blue up there and a single widening and blurred contrail that cleaved the heavens in perfect halves. “To the end of long journeys,” he said, raising his bottle. The small tree fort that sat in the crotch of an old maple at the far end of the garden was awash in afternoon sunlight. The fort was painted a cheerful Mediterranean blue that held the light with a sharp warm glow, and the driftwood and cedar trees that bordered the property seemed to lean inward, as if they were expectant of some rivalry that might now make itself known and listening intently.

“This is your place now. For as long as you want. Seriously. We set up a room upstairs.”

I told him I appreciated the offer, that it meant a lot to me, but I’d booked a room in a hotel downtown.

He insisted, shaking his head. “That’s not how it works here,” he said. “You’re our guest. Absolutely not. No way. You’re not leaving. The boys have been looking forward to this. They’ve heard all about Uncle Charlie now. You can’t just suddenly disappear. They’ve been talking nonstop about—” And with this he smiled and gestured over my shoulder. I turned and there were his sons, Titus and Quinn, big grins eating up their faces. They were both wearing baseball caps and long, brightly colored shorts. “Thing One and Thing Two,” he said.

Titus was ten that summer, two years younger than Ava, but he was already as tall. His head came up to my chin. I shook hands with both boys. They were perfect little gentlemen that afternoon.

“Welcome to Canada,” Titus said. “It’s very nice to meet you.” With his thick curly brown hair, he looked much like I did at that age. He was gangly and awkward, at the point in a boy’s life where muscle and coordination seem to disappear under the blitzkrieg of skeletal growth. Quinn, two years younger, was blond and cheerful as a brand-new sports shirt.

Both boys’ eyes were brown, like their dad’s, Ava’s, and our father’s. Well tanned and radiantly healthy, they’d just finished two weeks of canoe day camp on the Toronto Islands. They told me what sports and hobbies they’d done there, and I pulled out some pictures of their cousin and told them that she loved swimming and playing soccer, too, and that with any luck one day they’d meet.

“But why does she live over there?” Quinn said.

“That’s where she’s from, you idiot,” Titus said.

“She’s Spanish!”

“But Uncle Charlie’s not Spanish, are you?” Quinn said.

“I’m from here. Just like your dad. I went away for a long time. And now, poof, I’m back.”

Titus seemed to take this as a satisfactory explanation and then, apropos of nothing I was aware of, showed me what he’d learned in karate class earlier that week. He waved his little arms in the air and did a few turns and kicks, ending with a horizontal chop.

Quinn looked at me and rolled his eyes. “Okay, ninja boy,” he said.

There was no reason to think anything would be different between me and my brother the previous summer, in 2005, when I called ahead to tell him I was coming back to Toronto to try out my new life as a single man. I’d been studying the possibility of taking the business across the Atlantic for years, but for too many reasons to count, I’d never managed to pull it off. After finding out about the Supreme Court justice named Pablo, though, and having by then bunkered down at the Reina Victoria Hotel for two months, I was feeling sufficiently unsettled to actually do it. I needed some changes in my life. New schedule, new people, new rhythms. I was hoping for something else but wasn’t at all sure what it might be. The challenge of setting up my fifth language academy was a project that would focus my energies in the meantime and perhaps turn off the panicked voice in my head that kept telling me things I didn’t want to hear.

I wondered if some overlooked germ of hope had lain dormant in my heart over the years since I’d last seen my brother. But it wasn’t an easy telephone call to make at the time. There had always been some fundamental confusion between us, a wall, in effect an unending failure to imagine how the other saw and thought about the world that too often made things go sideways between us. That’s what had happened in Madrid the last time I’d seen him. We’d spoken by phone half a dozen times since then—on a birthday, his or mine, or the shared anniversary of our parents’ deaths—and I’d always come away glad to know he was well but also relieved that our lives were separate and distinct and that the problems between us might remain buried to the end of our days.

They had met only once, Isabel and Nate, when he came through Madrid back in 1992, the summer of the Barcelona Olympics and the Seville World’s Fair, after dumping the girl he was traveling with in France. He turned up at our door one night and told us he was heading down to check out the señoritas in Seville, then going back north to try to score some tickets for the sailing competitions in Catalonia. We put him up on the couch for a week. Showing him around my adopted hometown, I took him to the oldest restaurant in the world and spent a wad of money I didn’t really have. We wandered through neighborhoods packed with bars and clubs. Nothing seemed to impress him. In fact he found it all just a little bit irritating. The city was too hot and dirty and loud; he bitched and moaned about train schedules and shitty restaurants and the near-complete absence of spoken English in the streets and hotels. I got the impression that every- thing he saw in Spain made him feel superior, though of course he didn’t say as much. His last night with us he got stupidly drunk and said he wanted to go find some prostitutes. At first it was a joke I could almost brush aside. But he kept insisting. Then he draped his arm around Isabel’s neck and asked if out of the good- ness of her heart she could possibly loosen that grip she’d fastened around my balls, the boys just wanted to go out and have some fun for a change. That’s when I took him out for a drink he didn’t need and told him he could find some other couch to sleep on. I knew he had some experience with prostitutes. I didn’t care so much about that, since we both did. What I couldn’t stand was him treating Isabel as if she were some sort of obstacle in my life. The whole week had been building up to that moment. He’d been throwing out little put-downs and challenges, testing to see how far he could push me. When I told him what a selfish prick I thought he was, he took a swing at me right there in front of the bar. Not nearly as drunk as he was, I just stepped aside, went back to the apartment and took Isabel out to dinner. His backpack was gone when we got home a few hours later. The taps in the kitchen and bathroom were open full blast and a jug of water had been emptied into our bed. It was probably three or four years before I talked to him again.

So I was surprised, maybe even a little suspicious, I’ll admit now, when he offered to pick me up at the air- port. What might have changed, I wondered. A few hours into my flight I became convinced it had to be a misunderstanding and doubted he’d show. At baggage collection I watched an empty baby bassinet make three solitary revolutions and weighed my immediate prospects. I had a pocketful of euro coins that weren’t going to do me a lick of good here, a cell phone with thirty-seven Madrid numbers on speed dial and one single solitary local address written out on an old Post- it in my wallet. For an uncomfortable moment I felt something like a college student on the first leg of the big trip, tired, woefully underprepared and full of conflicting emotion. I saw my brother for an instant then—he was standing in the concourse—when the automatic doors that separated us opened. I almost didn’t recognize him, not because he’d changed—he hadn’t—but for the simple shock of seeing him there.

He was holding a newspaper in his right hand and wearing jeans and a green golf shirt. I might have smiled when I saw him—surprised he’d actually come to meet me—and then I wondered if he somehow knew I was limping home at the end of my marriage. Would he remind me, after thirteen years apart, that he’d always come out on top in the competition that seemed to rule us? Steeling myself, I collected my luggage and continued to the doors. He saw me and waved, and when we embraced, I recognized the cologne that our father had worn when we were boys. I didn’t know what it was called, but its scent opened my eyes like an old family photograph.

“My big little brother,” he said. “Welcome home.”

“It’s good to see you, Nate,” I said.

I’m taller than my brother by two fingers, have been since I caught up and passed him at the age of fourteen, and when we stood back from our embrace, he put his hand on my shoulder—the railing still separated us at hip level—and nodded and smiled as if some pleasant observation was registering in his mind. His hair was thick and dark, gelled or greased and cut short in a way that made him look younger than his years. He looked more or less as I remembered him. He was a fit and handsome man, like our father, with strong shoulders and a natural athletic grace that had favored him throughout and beyond his high school years. I couldn’t begin to imagine how much my appearance had changed since then. I had expected a similar aging in my brother, of course, the beginnings of a paunch or the thinning of hair that followed on our father’s side. But there was no hint of that. The years seemed to have passed him by. His face was still unlined and youthful-looking, his dark hair was thick as ever, and he wore the same conspiratorial and dazzling smile he’d used to his advantage when we were kids.

There were no awkward silences between us that day. As he drove me into the city—we were riding in air-conditioned comfort in a big white Escalade that afforded us a bird’s-eye view of the laps of the drivers in the next lane—he mentioned his kids three or four times, how great they were, what they did for fun, how he liked nothing more than hanging out in the back- yard and grilling hot dogs and burgers for them. Sticking to the upside of my life, I told him that Ava was an athletic and popular kid, almost twelve years old at that point, a kid who loved to read, did great in school and had a knack for languages. “Can you believe it? Us as dads,” he said. “The mind boggles.”

A few minutes later he pointed out an office tower in the distance, tall and glassy and shimmering in the afternoon sunshine, sixty stories of gold-tinted windows. He was a partner with one of the big law firms in that building, specializing in sports and entertainment. His client list had a number of golf and baseball and hockey players on it. The only name that stood out for me was a young female tennis player’s, likely because I’d always kept an eye on that game for its connection to memories of summer evenings spent rallying tennis balls against the south wall of my high school. Cycling, tennis and swimming had been my areas of concentration, solitary sports whose lack of bullish camaraderie seemed to make him suspicious at the time.

“Sounds like you enjoy what you do,” I said.

“There aren’t a lot of guys around these days who can make that claim.”

“I’m not saying life’s perfect where I’m sitting. I’ve got a bit of a domestic situation going on.”

“Oh?”

He told me that Monica—his sons’ mother—had moved out in April, three days after tossing her wedding band into the Toronto harbor at the end of a night on the town with three girlfriends. Now she was living with an older Swedish man who owned what he described as a multidimensional sports-and-entertainment complex for the modern adventure-seeking kid, a high- end, one-stop birthday emporium called Wonderworld. The man in question had come over from Scandinavia in the early nineties and doggedly built a chain of these franchises across the country.

“That’s where she met the guy. At our kid’s tenth birthday party. Nice, eh?”

“I’m sorry to hear it,” I said.

Since then Nate and Monica had hashed out an agreement where the kids were concerned. Everything else was still up in the air. Technically he took his sons every other week, but now he was traveling so much and so often that he was barely able to keep up his end of the deal. His tone when he told me this wasn’t whiny or bitter, not on that first afternoon, anyway. If anything he seemed contemplative—a word I never expected to use to describe my brother. But that’s how he came off that day as he drove me into the city. It seemed he’d been humbled. It stood to reason. You can’t go through something like that and not be.

I listened to the rest of his story, then told him something of my own great humbling. The two stories were dishearteningly similar.

He nodded in agreement. “Yeah,” he said, “that sounds just about right. Bang, bang, bang. Half the marriages on our street have gone bust. It’s a freaking epidemic here. Maybe it’s different in those Catholic countries. But here . . .” He shook his head again, then smiled.

“What?”

“You know those little fridge magnets? The ones with writing on them? Some little bead of wisdom or saying or whatever to warm your day.”

“Sure. I think so.”

“We had one on our fridge forever. I didn’t think much about it. I thought it was just a joke. It used to give me a laugh.”

“What did it say?”

“‘Men are like floors. If you lay them right the first time, you can walk all over them for years.’ ” He smiled a big genuine smile.

“Who’s going to argue with that, right?” I said.

“But that was her basic philosophy. Typical passive- aggressive bullshit that women get away with all the time now. Maybe it’s different over in Spain, who knows? But a guy puts some sexist joke about women on his fridge here, he’s automatically a misogynist and creepy asshole. Stay long enough, you’ll see for yourself.”

Nate lived in the city’s east end, two blocks north of the old Don Jail, in a nice-looking neighborhood set at the edge of a deep, wide valley. When he led me through his house that afternoon he told me it had been featured in House & Home and Architectural Digest; he managed to impart this information without seeming to brag, though of course that’s exactly what he was doing. He directed my attention to an oversize book on the coffee table called Rustic Cottage Ontario, and when he flipped it open to a photograph showing the vacation property he’d recently bought two hours north of the city, I told him it looked like things were going well for him.

And it was true. The walls in the room he’d led me into were hung with colorful paintings, and the hardwood floors were covered in fine rugs. The overall feel of the place was original, homey and expensive. It seemed he’d made himself into a success. But I hadn’t intended the comment to be understood this way, if in fact it had been. I’d meant to say that he’d taken his life in a positive direction, or so it appeared, given what the details seemed to suggest. Despite the domestic situation he’d referred to, my brother had ended up a family man, or at least some version of one. I saw the traces everywhere: a golf putter, a base- ball glove, a heavily thumbed copy of the latest Harry Potter; playing cards were scattered over the dining room table; a Monopoly set was open midgame on the coffee table beside the cottage book. Someone had left a skateboard in the middle of the living room floor, and rather than cursing and stepping over it as we moved into the kitchen he lowered his foot decisively against its stern, and the board obediently popped up into his hand, and he tucked it under his arm with a smile. It was a trick he might have per- formed in the family driveway thirty-five years before. And that’s when I wondered for the first time if my brother had truly changed. Had I judged him too harshly? Had I even remembered him correctly after all those years?

Two cats appeared from behind a couch, one black, one white, and disappeared up the carpeted stairs. He leaned the skateboard against the wall, its wheels still spinning noiselessly, and grabbed two bottles of Heineken from the fridge. We stepped out into the backyard. Overhead was the sort of sky that seems to go on forever. There was nothing but blue up there and a single widening and blurred contrail that cleaved the heavens in perfect halves. “To the end of long journeys,” he said, raising his bottle. The small tree fort that sat in the crotch of an old maple at the far end of the garden was awash in afternoon sunlight. The fort was painted a cheerful Mediterranean blue that held the light with a sharp warm glow, and the driftwood and cedar trees that bordered the property seemed to lean inward, as if they were expectant of some rivalry that might now make itself known and listening intently.

“This is your place now. For as long as you want. Seriously. We set up a room upstairs.”

I told him I appreciated the offer, that it meant a lot to me, but I’d booked a room in a hotel downtown.

He insisted, shaking his head. “That’s not how it works here,” he said. “You’re our guest. Absolutely not. No way. You’re not leaving. The boys have been looking forward to this. They’ve heard all about Uncle Charlie now. You can’t just suddenly disappear. They’ve been talking nonstop about—” And with this he smiled and gestured over my shoulder. I turned and there were his sons, Titus and Quinn, big grins eating up their faces. They were both wearing baseball caps and long, brightly colored shorts. “Thing One and Thing Two,” he said.

Titus was ten that summer, two years younger than Ava, but he was already as tall. His head came up to my chin. I shook hands with both boys. They were perfect little gentlemen that afternoon.

“Welcome to Canada,” Titus said. “It’s very nice to meet you.” With his thick curly brown hair, he looked much like I did at that age. He was gangly and awkward, at the point in a boy’s life where muscle and coordination seem to disappear under the blitzkrieg of skeletal growth. Quinn, two years younger, was blond and cheerful as a brand-new sports shirt.

Both boys’ eyes were brown, like their dad’s, Ava’s, and our father’s. Well tanned and radiantly healthy, they’d just finished two weeks of canoe day camp on the Toronto Islands. They told me what sports and hobbies they’d done there, and I pulled out some pictures of their cousin and told them that she loved swimming and playing soccer, too, and that with any luck one day they’d meet.

“But why does she live over there?” Quinn said.

“That’s where she’s from, you idiot,” Titus said.

“She’s Spanish!”

“But Uncle Charlie’s not Spanish, are you?” Quinn said.

“I’m from here. Just like your dad. I went away for a long time. And now, poof, I’m back.”

Titus seemed to take this as a satisfactory explanation and then, apropos of nothing I was aware of, showed me what he’d learned in karate class earlier that week. He waved his little arms in the air and did a few turns and kicks, ending with a horizontal chop.

Quinn looked at me and rolled his eyes. “Okay, ninja boy,” he said.

Recenzii

“Finely crafted, disarmingly casual prose that quietly penetrates the reader’s mind and heart…. On one level, the novel captures the difficulty men have reading woman; on a deeper level, Bock plumbs issue of memory, moral responsibility and what constitutes a man’s real love for a woman.” —Kirkus Reviews (starred)

“Excellent, and sensitively written. Going Home Again is a story bound up in complex emotions and subtle character development, sad and yet hopeful with its haunting reminder that we are damned or redeemed by our passions.” —Linden MacIntyre, Giller Prize-winning author of The Bishop’s Man and Why Men Lie

“A tense, riveting, beautifully layered novel, Going Home Again is an exquisite story of a complex and troubled family. Dennis Bock is a superb writer.” —Steven Galloway, author of The Cellist of Sarajevo

“Excellent, and sensitively written. Going Home Again is a story bound up in complex emotions and subtle character development, sad and yet hopeful with its haunting reminder that we are damned or redeemed by our passions.” —Linden MacIntyre, Giller Prize-winning author of The Bishop’s Man and Why Men Lie

“A tense, riveting, beautifully layered novel, Going Home Again is an exquisite story of a complex and troubled family. Dennis Bock is a superb writer.” —Steven Galloway, author of The Cellist of Sarajevo

Premii

- Scotiabank Giller Prize Finalist, 2013