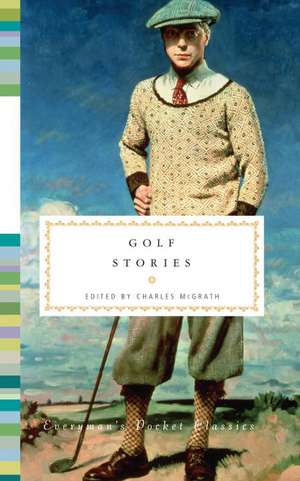

Golf Stories

Editat de Charles McGrathen Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 mar 2011

Here are literary classics by such golf-loving writers as P. G. Wodehouse, Ring Lardner, and John Updike, mixed with surprises like an appearance by Ian Fleming’s James Bond and a little crime on the links from mystery master Ian Rankin. Humorists and sportswriters ranging from E. C. Bentley to Dan Jenkins and Rick Reilly weigh in as well, alongside a tale of romance on the greens from F. Scott Fitzgerald, a little-known gem by famous golf architect A. W. Tillinghast, and a story by Rex Lardner (Ring’s nephew) that just may be the single funniest thing ever written about golf. The resulting anthology is as enticing, provocative, and entertaining as the game of golf itself.

Preț: 111.37 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 167

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.31€ • 22.22$ • 17.71£

21.31€ • 22.22$ • 17.71£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307596895

ISBN-10: 0307596893

Pagini: 331

Dimensiuni: 126 x 182 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Everyman's Library

ISBN-10: 0307596893

Pagini: 331

Dimensiuni: 126 x 182 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.36 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Everyman's Library

Notă biografică

Charles McGrath is a writer at large at The New York Times, and was formerly editor of The New York Times Book Review and deputy editor of The New Yorker. He is co-author of The Ultimate Golf Book and a frequent contributor to Golf Digest. He lives in New Jersey.

Extras

From the Forward by Charles McGrath

George Plimpton used to invoke what he called the small-ball theory of sportswriting — the idea that the quality of the literature about a game is inversely proportional to the size of the ball it employs. This notion was always a little sketchy. Where are the great ping-pong writers, the classic works on marbles? And yet when it comes to fiction about sports there may be some truth here, for the golf ball, whether dimpled, feathery or guttie, has probably inspired more good short stories than any of the larger rounder things. A great majority of these stories are humorous, which seems a little counter-intuitive at first, because golf when you play it — or what I play, anyway — is not particularly funny at all. Tragic is more like it.

The other form that golf fiction seems to gravitate towards is mystery, and that seems more appropriate. To most of us the game is a puzzle we will never solve, and it's also not uncommon for a golfer to think a murderous thought or two. What recommends both genres — comedy and mystery — is that they offer resolution and impose a shapeliness and orderliness on a game that often seems so random and arbitrary and in which punishments are often cruelly out of whack with the mistake that incurs them.

Golf fiction, in other words, is escape-reading in the best sense. It lifts us from the rigors, uncertainty, and injustice of golf as it is actually played and unfolds for us another, more satisfying and lighthearted world in which everything makes sense in the end. In that respect golf fiction is a lot like the stories we tell ourselves, playing a round over again in our heads on the way home, or each other, lingering in the club house over a cold one. Golf itself is a narrative of sorts. We set off and journey outward, full of hope and purpose; we're tested, we suffer, we experience a few momentary glimpses of bliss; and then we turn and head for home, our progress grimly charted by those numbers inexorably mounting on the card. Then, in the retelling, we make it all sound a little better, a little cheerier. That 90 you shot could easily have been an 80; for all practical purposes it was, in fact. Golf stories are the imaginative equivalent of nudging the ball to improve your lie. They give you a little lift.

In putting together this anthology I've tried to give some sense of the range and variety of golf fiction over the years, and the stories are arranged in roughly chronological order to suggest how golf, or writing about it, has evolved. A lot of the selections were self-evident. That there would be a story by P. G. Wodehouse, for example, was a no-brainer. The chore, if you can call it that, was deciding which one, and I spent many happy hours reading and rereading Wodehouse's dozens of golf stories before throwing up my hands and deciding that it almost didn't matter. They are all pretty wonderful, practically interchangeable.

That John Updike's story "Farrell's Caddy" would be here was also a foregone conclusion. To my mind it's the best golf story ever: funny, surprising, beautifully written, and sneakily insightful about the relationship that sometimes develops between a player and his caddy. This is one of those golf stories that rise from the escape-reading to genuine greatness. Another is F. Scott Fitzgerald's "Winter Dreams," which you could argue is barely a golf story at all. For me, the story, which was written before The Great Gatsby, merits inclusion for the interesting way it uses golf not as a setting or a plot device but as a symbol or emblem of class, wealth, and longing — all the great Fitzgerald preoccupations. It's also the deepest exploration I know of a persistent little sub-theme that pops up often in golf fiction, especially in Wodehouse: the mysterious link between golf and the distant, unattainable female.

Without something by Rick Reilly and Dan Jenkins a book like this would hardly be complete, and how could I leave out the great golf chapter — a story in itself — from Ian Fleming's Goldfinger? Nor should it be a surprise that so many stories here are from the Twenties and Thirties, the Golden Age not just of golf fiction but of sports fiction in general.

Along the way, though, I also made some surprising discoveries. I knew, for example, that Bernard Darwin, the great English golf chronicler, had written some golf fiction, but I never imagined that his disciple, Herbert Warren Wind, for so many years The New Yorker's golf writer, had done so as well. And who knew that A. W. Tillinghast, the golf architect who created masterpieces like Winged Foot, Baltusrol, and Bethpage Black, wrote golf fiction? I certainly didn't. Tillinghast's stories are not, in truth, nearly as good as his golf courses, but that he wrote them at all is testament to his energy and enterprise. During this same period he also tried to build an indoor miniature golf course in New York that would be a front for a speakeasy.

Careful readers of a more literary bent may notice some curious lines of influence and relationship here. Rex Lardner, whose Out of the Bunker and Into the Trees, both a parody of golf writing and an inspired addition to it, deserves to be far better known, was Ring Lardner's nephew. Ring Lardner, represented here by one of his lesser-known efforts, "Mr. Frisbie," is more famous for his baseball stories, especially the novel You Know Me Al, of which Herbert Warren Wind's Harry Sprague story is a transparent imitation. Or maybe translation is a better word. Wind took Lardner's conceit — a series of letters written by a clueless, swollen-headed and semi-literate athlete — and switched it over from baseball to golf with equally foolproof results. Similarly, James Kaplan's story "The Mower" — an anti-golf story, really — was clearly inspired by Updike's classic short story "A & P." And my own contribution, "Sneaking On," about a guy trying to play his way across town from one golf course to another, is a fairly shameless rip-off of John Cheever's great story "The Swimmer." Good golfers know that you can always borrow a trick or two from the pros, and writing golf fiction is no different.

Finally a number of the stories here were written early enough that they use the old-fashioned names for golf clubs, so here's a conversion table:

Brassie = No. 2 wood

Spoon = No. 3 wood

Cleek = 2-iron

Mid-mashie = 3-iron

Mashie = 5-iron

Spade mashie = 6-iron

Mashie niblick = 7-iron

Niblick = 9-iron

Baffing spoon = wedge.

George Plimpton used to invoke what he called the small-ball theory of sportswriting — the idea that the quality of the literature about a game is inversely proportional to the size of the ball it employs. This notion was always a little sketchy. Where are the great ping-pong writers, the classic works on marbles? And yet when it comes to fiction about sports there may be some truth here, for the golf ball, whether dimpled, feathery or guttie, has probably inspired more good short stories than any of the larger rounder things. A great majority of these stories are humorous, which seems a little counter-intuitive at first, because golf when you play it — or what I play, anyway — is not particularly funny at all. Tragic is more like it.

The other form that golf fiction seems to gravitate towards is mystery, and that seems more appropriate. To most of us the game is a puzzle we will never solve, and it's also not uncommon for a golfer to think a murderous thought or two. What recommends both genres — comedy and mystery — is that they offer resolution and impose a shapeliness and orderliness on a game that often seems so random and arbitrary and in which punishments are often cruelly out of whack with the mistake that incurs them.

Golf fiction, in other words, is escape-reading in the best sense. It lifts us from the rigors, uncertainty, and injustice of golf as it is actually played and unfolds for us another, more satisfying and lighthearted world in which everything makes sense in the end. In that respect golf fiction is a lot like the stories we tell ourselves, playing a round over again in our heads on the way home, or each other, lingering in the club house over a cold one. Golf itself is a narrative of sorts. We set off and journey outward, full of hope and purpose; we're tested, we suffer, we experience a few momentary glimpses of bliss; and then we turn and head for home, our progress grimly charted by those numbers inexorably mounting on the card. Then, in the retelling, we make it all sound a little better, a little cheerier. That 90 you shot could easily have been an 80; for all practical purposes it was, in fact. Golf stories are the imaginative equivalent of nudging the ball to improve your lie. They give you a little lift.

In putting together this anthology I've tried to give some sense of the range and variety of golf fiction over the years, and the stories are arranged in roughly chronological order to suggest how golf, or writing about it, has evolved. A lot of the selections were self-evident. That there would be a story by P. G. Wodehouse, for example, was a no-brainer. The chore, if you can call it that, was deciding which one, and I spent many happy hours reading and rereading Wodehouse's dozens of golf stories before throwing up my hands and deciding that it almost didn't matter. They are all pretty wonderful, practically interchangeable.

That John Updike's story "Farrell's Caddy" would be here was also a foregone conclusion. To my mind it's the best golf story ever: funny, surprising, beautifully written, and sneakily insightful about the relationship that sometimes develops between a player and his caddy. This is one of those golf stories that rise from the escape-reading to genuine greatness. Another is F. Scott Fitzgerald's "Winter Dreams," which you could argue is barely a golf story at all. For me, the story, which was written before The Great Gatsby, merits inclusion for the interesting way it uses golf not as a setting or a plot device but as a symbol or emblem of class, wealth, and longing — all the great Fitzgerald preoccupations. It's also the deepest exploration I know of a persistent little sub-theme that pops up often in golf fiction, especially in Wodehouse: the mysterious link between golf and the distant, unattainable female.

Without something by Rick Reilly and Dan Jenkins a book like this would hardly be complete, and how could I leave out the great golf chapter — a story in itself — from Ian Fleming's Goldfinger? Nor should it be a surprise that so many stories here are from the Twenties and Thirties, the Golden Age not just of golf fiction but of sports fiction in general.

Along the way, though, I also made some surprising discoveries. I knew, for example, that Bernard Darwin, the great English golf chronicler, had written some golf fiction, but I never imagined that his disciple, Herbert Warren Wind, for so many years The New Yorker's golf writer, had done so as well. And who knew that A. W. Tillinghast, the golf architect who created masterpieces like Winged Foot, Baltusrol, and Bethpage Black, wrote golf fiction? I certainly didn't. Tillinghast's stories are not, in truth, nearly as good as his golf courses, but that he wrote them at all is testament to his energy and enterprise. During this same period he also tried to build an indoor miniature golf course in New York that would be a front for a speakeasy.

Careful readers of a more literary bent may notice some curious lines of influence and relationship here. Rex Lardner, whose Out of the Bunker and Into the Trees, both a parody of golf writing and an inspired addition to it, deserves to be far better known, was Ring Lardner's nephew. Ring Lardner, represented here by one of his lesser-known efforts, "Mr. Frisbie," is more famous for his baseball stories, especially the novel You Know Me Al, of which Herbert Warren Wind's Harry Sprague story is a transparent imitation. Or maybe translation is a better word. Wind took Lardner's conceit — a series of letters written by a clueless, swollen-headed and semi-literate athlete — and switched it over from baseball to golf with equally foolproof results. Similarly, James Kaplan's story "The Mower" — an anti-golf story, really — was clearly inspired by Updike's classic short story "A & P." And my own contribution, "Sneaking On," about a guy trying to play his way across town from one golf course to another, is a fairly shameless rip-off of John Cheever's great story "The Swimmer." Good golfers know that you can always borrow a trick or two from the pros, and writing golf fiction is no different.

Finally a number of the stories here were written early enough that they use the old-fashioned names for golf clubs, so here's a conversion table:

Brassie = No. 2 wood

Spoon = No. 3 wood

Cleek = 2-iron

Mid-mashie = 3-iron

Mashie = 5-iron

Spade mashie = 6-iron

Mashie niblick = 7-iron

Niblick = 9-iron

Baffing spoon = wedge.

Descriere

A wonderful gathering of short fiction about the famously addictive pastime featuring classics by such golf-loving writers as P.G. Wodehouse, Ring Lardner, and John Updike, mixed with surprises like an appearance by Ian Fleming's James Bond and a little crime on the links from mystery master Ian Rankin.