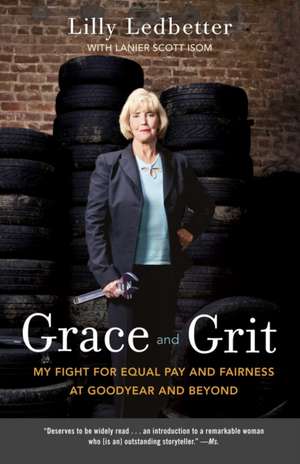

Grace and Grit: My Fight for Equal Pay and Fairness at Goodyear and Beyond

Autor Lilly Ledbetter, Lanier Scott Isomen Limba Engleză Paperback – 25 feb 2013

Lilly Ledbetter always knew that she was destined for something more than what she was born into--a house with no running water or electricity in the small town of Possum Trot, Alabama. In 1979, when Lilly applied for her dream job at the Goodyear tire factory, she got the job--one of the first women hired at the management level. Nineteen years after her first day at Goodyear, Lilly received an anonymous note revealing that she was making thousands less per year than the men in her position.

When she filed a sex-discrimination case against Goodyear, Lilly won--and then heartbreakingly lost on appeal. Over the next eight years, her case made it all the way to the Supreme Court, where she lost again. But Lilly continued to fight, and became the namesake of Barack Obama's first official piece of legislation as president. A winning memoir and a powerful call to arms, Grace and Grit is the story of a true American icon.

Preț: 115.94 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 174

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.19€ • 23.03$ • 18.50£

22.19€ • 23.03$ • 18.50£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 01-15 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780307887948

ISBN-10: 0307887944

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 129 x 208 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

ISBN-10: 0307887944

Pagini: 288

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 129 x 208 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.21 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

LILLY LEDBETTER was an overnight supervisor at the Alabama Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. for 19 years. She was the plaintiff in the American employment discrimination case Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. and inspired the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Restoration Act.

Extras

Chapter 1

Possum Trot

Have you heard of the Nothing impossible possum Whose faith and belief made His dream to blossom?

--Marjorie Ainsborough Decker, The Christian Mother Goose Book of Nursery Rhymes

If you grow up in Possum Trot, Alabama, you run across some rough characters from time to time. You might even be related to a few. In truth, the tough guys at Goodyear weren't a far cry from what I'd seen and heard in the fields picking cotton or in the barn helping milk the cows at Aunt Lucille's dairy farm.

I'll never forget the afternoon when my grandfather, Papa, decided he wanted to kill my dog, Buzz. Papa, who claimed to be part Irish, was so pale that he looked part ghost. I'm honestly not sure there was any good in him, but I can also say that he wasn't all that different from most of the other men around me.

I was only five the day Papa came after Buzz, but my memory of that afternoon is clear as day. I was playing tea party in the front yard, scooping up dirt with a broken teacup Granny Mac had given me, and Buzz was my honored guest. As I set down a cup in front of Buzz, I heard Papa hollering down the road. I looked back at the house, hoping to see that Mama was still right inside the screen door cooking supper, and that she'd hear the racket in time to come out and protect me and Buzz. She wasn't. As Papa's large figure approached us, my stomach clenched. He was carrying something; it looked like a hoe.

I'd never had a pet before, unless you count the rooster who used to follow me around. But one day Buzz had appeared out of nowhere. We immediately took to each other. He was a funny little dog, brown and white and black with one dark spot shaped like a pumpkin seed on the top of his forehead. I used to rub that spot like it was a good-luck penny. I figured his breed was part everything, with his big hound-dog eyes, those large feet he slapped in front of him like clown shoes, and that mismatched coloring pieced together like a crazy quilt.

By the time Papa was close enough for me to make out what he was saying, Buzz had scooted under the house. "Where's that goddam worthless mutt?" he yelled. "He ain't worth killing."

I couldn't say a word. I couldn't even move. My mouth was as dry as if I'd swallowed the cup of dirt. All I could think about was how Papa would slaughter the pigs in the smokehouse. I always got attached to one of them, so I made a point of being as far away from the smokehouse as possible when killing time came. I wanted no part of wash pots filled with boiling-hot water and the hanging, splitting, and dressing of the meat. But I did show up about the time sausage was frying in the deep black skillet.

"Goddammit, Lilly. You better mind me and get that dog." Papa's eyes were moist and almost closed, like they had Vaseline smeared on them. He turned around and around in a circle trying to find Buzz, almost falling. He was drunk, really drunk. He lurched toward me, and I jumped up. Buzz must have thought Papa was going to hurt me because he shot out from under the porch, growling and circling us. Papa lunged at him, slicing the hoe through the air. I tried to stay between Papa and Buzz, never even thinking that I might get hit.

As we continued to dance around each other, the screen door slapped shut at last, and Mama came out screaming at Papa. His face and large nose flushed red above his white collared shirt buttoned to the top under his overalls. But other than that he didn't pay Mama a bit of attention as he, Buzz, and I continued to waltz around each other, the hoe thudding hard whenever it hit the ground.

"I mean it, Tot," she said, using the name everyone (but me) called him. "Don't make no sense to be scaring Lilly like that. Put it down."

But he was having none of it. He seemed to get madder and madder, and the hoe seemed closer to Buzz with every swing.

Suddenly Mama flew down the front steps, a long butcher knife in her hand, the same knife she always sharpened on the pedaling wheel before Papa killed the hogs. But not even the knife seemed to sway him. Papa, three times as big as she was, towered above her.

"Go on, Lilly. Get in the house," Mama said. I could see the look in her eyes, the fear and hatred that made her seem as wild as a rabid dog. I ran up onto the porch and, thankfully, Buzz followed.

Papa's eyes flashed anger at me as I stared at him through the screen door, my breath coming in quick gasps.

"Go on home and leave that dog alone," Mama said. She kept that butcher knife raised and pointed at him the whole time, jabbing it a few times in his direction when his temper flared back up. He dropped the hoe at last, and Mama backed him all the way down the steep driveway to the dirt road. And he left, lumbering and swaying his way back home.

As I watched this scene, I felt like I was suffocating, as if someone had stuck a sack of cotton over my head. I'd heard Mama tell my father how Papa had beaten her as a child. When she was little and he got to drinking, one of his buddies would rush to the house to warn my grandmother that Papa was headed home. She'd hustle the four boys and my mother out of bed to make a run for the barn, hiding in the hay for the rest of the night. Other times, without warning, Papa barged into their bedrooms, hickory stick in hand, and the beatings began.

After that day, I still rode on top of Papa's wagon and helped him feed the cows and guinea hens, but I never trusted him again. I remember telling myself I'd better be careful about who I let myself love. It was likely they'd turn on you. I also realized it was a good idea to have a knife nearby whenever possible.

Not long after, Buzz disappeared. I figured he just wandered off. Thankfully, it never occurred to me then that Papa might have gotten his way after all.

Many years later, when I first started working at Goodyear, the union guys liked to tell the women that they were going to "pick" us. That is, they were going to catch us and pick each pubic hair from our bodies. Like so much that happened there, when you put it in words and see it on paper, it sounds too unreal to believe. But they were always up to some prank or another, often making work a dangerous sport.

One day, a woman worker, fed up with the constant haranguing, actually dropped her pants and dared the men to do it. With her pants bunched around her ankles, she stood there in her plain white underwear. The guys backed off her but kept up their nonsense with the rest of us. I knew I'd never do what she did, but I also knew they often made good on their word, one time pinning down one of the new young guys and picking him clean. I went home and found one of Charles's knives to carry in my pocket, the hard leather sheath resting against my thigh in case they ever decided to test me.

Countless times throughout the years at Goodyear when I needed courage, I remembered how Mama had finally tamed Papa that summer afternoon. I never doubted my mother would have used the butcher knife that day, and in my moments of fear and anger, I never doubted I'd use my own knife if necessary.

The place where I grew up during the 1940s is a small bend in the road along the foot of Choccolocco Mountain in northeast Alabama. Just like those pinch-faced gray possums that roamed the pine forests, the people in that small community in the foothills of the Appalachians knew a thing or two about survival. They worked in the cotton or steel mills or scratched a living from the dirt. Some worked in the foundries or the army depot in nearby Anniston or, if they were lucky, had a good-paying job at Goodyear in Gadsden. The folks I knew would walk over broken glass to help a neighbor and just as soon kill you if you did them wrong.

In 1946, I was in second grade when my father came home from the navy and my parents bought land from Papa to build a slightly bigger house across the road from him. Life started looking up for my family then. It took me a while to adjust to the gleam from the naked bulb hanging off the thin cord from the ceiling, since I'd been so used to the soft glow of gaslight. A couple of years later, we got indoor plumbing and things really changed for the better. Gone were the days of tiptoeing through the wet grass in the black of night, wondering if I'd step on a rattlesnake on the way to the outhouse.

Our new house wasn't much to look at, but we were lucky. We were the only ones in Possum Trot, besides the brick mason, who owned a television. Daddy worked the night shift at the Anniston Army Depot six days a week, where he reworked engines on the battered military tanks sent home from Korea and later from Vietnam and the Middle East. Before we bought the TV, in the evenings when Daddy was gone, Mama and I had nowhere to go and nothing to do--except for Saturday evening, when we turned on the radio, silent all week to save batteries, and listened to the Grand Ole Opry. But once we got the TV, folks gathered in every corner and doorway of our small house many evenings to watch the nightly news.

During the day, I had to come up with my own entertainment, and I ran wild, disappearing for hours to climb trees and explore the woods. My cousin Louise and I spent entire days searching for caves or hunting for arrowheads in the Indian cemetery. We also loved to mimic the holy dancing we saw at the church campground down the road.

Despite these wistful memories, nearly all of my childhood was spent in endless work. In the misty summer mornings Mama and I picked beans and okra before the sun started blazing down on us. After we headed back to the house to bathe and change, we spent the rest of the day hulling peas, skinning tomatoes, and blanching vegetables to can for the winter. We only stopped canning to sleep. On the weekends we roamed the woods to fill our syrup buckets with huckleberries and blackberries for jam and cobbler, slapping the itchy bites from the invisible chiggers with Listerine to keep them from driving us crazy.

Growing up, I never lacked for essentials, and I certainly never went hungry. I knew we were better off than a good many folks. Of course, I was also painfully aware that we weren't as well off as some others--like my best friend, Sandra. I'd known her since first grade. While I wore homemade bloomers, Sandra could afford silk panties. Every day she came to school in a coordinated sweater and skirt, never without a perfect strand of pearls. Even the teachers called her "little princess."

Sandra's family lived in New Liberty, a neighborhood where no one whitewashed their trees or kept chickens running around the front yard. There, children didn't have to share a bedroom with their grandmother, like I did. Sitting in front of the large mirror at Sandra's elegant dressing table, I'd angle her hand mirror every which way to see my reflection, hoping to improve my profile. But there it always was, clear as day, the bump in the middle of my nose, the same mysterious Indian nose as Granny Mac's and Daddy's.

Every time I came home from Sandra's, I felt inferior. Just the sight of my dingy white house and dusty dirt yard made me ashamed even though I knew how far we'd come. I dared not say anything about my disappointment. I saw how hard my parents worked. But the older I got, the more transparent the differences in my life and Sandra's became, and my sense of embarrassment stayed with me, as indelible as a birthmark. I was keenly aware that all this privilege was due to Goodyear, where Sandra's father worked. New Liberty was where the Goodyear families lived. And it's where, more than anywhere, I wanted to be.

I used to stare at the Goodyear plant when I passed it on my annual summer Greyhound bus trip to Aunt Mattie Bell and Uncle Hoyt's small duplex house in Gadsden. Right before you got into town, there was the plant, next to the Coosa River. A giant redbrick building with slits for windows, it sprawled for blocks behind a tall steel fence like a fortress. The huge smokestacks billowed black smoke. Riding past the plant, I dreamed about what it would have been like to ride around in a brand-new Mercury every few years like Sandra. Or I imagined swimming in the Gulf Coast during spring break like she did. I even fantasized about how smooth my hands would be if my daddy worked at Goodyear. Maybe even best of all, if he did, I'd never have to pick cotton again.

All my life I'd been surrounded by one continuous cotton field. I started picking cotton there before I entered first grade and had been picking ever since. It was the only job around, and I was in the field every weekend with my cousin Louise making extra money for the family. When I was older, during the summer Louise and I chopped cotton before it matured in order to earn some spending money of our own. We slung our hoes into the ground, attacking the johnsongrass that spread like gossip between the rows, sputtering complaints to each other that we dared not offer to anyone else. It wasn't just the cotton. When we picked corn, we bellyached the same way, row after row, as cornstalks slapped our bare necks and scratched our hands.

At the end of the day, two men shouldered a pole between them and hooked our sack of cotton onto the P ring as Papa--all six foot five of him--loomed above me and slid a heavy metal ball across the bar to determine how many pounds we'd plucked from the prickly stalks. It took days to fill our long, skinny sacks. Sometimes it felt like I was trying to fill the sack with clouds.

Possum Trot

Have you heard of the Nothing impossible possum Whose faith and belief made His dream to blossom?

--Marjorie Ainsborough Decker, The Christian Mother Goose Book of Nursery Rhymes

If you grow up in Possum Trot, Alabama, you run across some rough characters from time to time. You might even be related to a few. In truth, the tough guys at Goodyear weren't a far cry from what I'd seen and heard in the fields picking cotton or in the barn helping milk the cows at Aunt Lucille's dairy farm.

I'll never forget the afternoon when my grandfather, Papa, decided he wanted to kill my dog, Buzz. Papa, who claimed to be part Irish, was so pale that he looked part ghost. I'm honestly not sure there was any good in him, but I can also say that he wasn't all that different from most of the other men around me.

I was only five the day Papa came after Buzz, but my memory of that afternoon is clear as day. I was playing tea party in the front yard, scooping up dirt with a broken teacup Granny Mac had given me, and Buzz was my honored guest. As I set down a cup in front of Buzz, I heard Papa hollering down the road. I looked back at the house, hoping to see that Mama was still right inside the screen door cooking supper, and that she'd hear the racket in time to come out and protect me and Buzz. She wasn't. As Papa's large figure approached us, my stomach clenched. He was carrying something; it looked like a hoe.

I'd never had a pet before, unless you count the rooster who used to follow me around. But one day Buzz had appeared out of nowhere. We immediately took to each other. He was a funny little dog, brown and white and black with one dark spot shaped like a pumpkin seed on the top of his forehead. I used to rub that spot like it was a good-luck penny. I figured his breed was part everything, with his big hound-dog eyes, those large feet he slapped in front of him like clown shoes, and that mismatched coloring pieced together like a crazy quilt.

By the time Papa was close enough for me to make out what he was saying, Buzz had scooted under the house. "Where's that goddam worthless mutt?" he yelled. "He ain't worth killing."

I couldn't say a word. I couldn't even move. My mouth was as dry as if I'd swallowed the cup of dirt. All I could think about was how Papa would slaughter the pigs in the smokehouse. I always got attached to one of them, so I made a point of being as far away from the smokehouse as possible when killing time came. I wanted no part of wash pots filled with boiling-hot water and the hanging, splitting, and dressing of the meat. But I did show up about the time sausage was frying in the deep black skillet.

"Goddammit, Lilly. You better mind me and get that dog." Papa's eyes were moist and almost closed, like they had Vaseline smeared on them. He turned around and around in a circle trying to find Buzz, almost falling. He was drunk, really drunk. He lurched toward me, and I jumped up. Buzz must have thought Papa was going to hurt me because he shot out from under the porch, growling and circling us. Papa lunged at him, slicing the hoe through the air. I tried to stay between Papa and Buzz, never even thinking that I might get hit.

As we continued to dance around each other, the screen door slapped shut at last, and Mama came out screaming at Papa. His face and large nose flushed red above his white collared shirt buttoned to the top under his overalls. But other than that he didn't pay Mama a bit of attention as he, Buzz, and I continued to waltz around each other, the hoe thudding hard whenever it hit the ground.

"I mean it, Tot," she said, using the name everyone (but me) called him. "Don't make no sense to be scaring Lilly like that. Put it down."

But he was having none of it. He seemed to get madder and madder, and the hoe seemed closer to Buzz with every swing.

Suddenly Mama flew down the front steps, a long butcher knife in her hand, the same knife she always sharpened on the pedaling wheel before Papa killed the hogs. But not even the knife seemed to sway him. Papa, three times as big as she was, towered above her.

"Go on, Lilly. Get in the house," Mama said. I could see the look in her eyes, the fear and hatred that made her seem as wild as a rabid dog. I ran up onto the porch and, thankfully, Buzz followed.

Papa's eyes flashed anger at me as I stared at him through the screen door, my breath coming in quick gasps.

"Go on home and leave that dog alone," Mama said. She kept that butcher knife raised and pointed at him the whole time, jabbing it a few times in his direction when his temper flared back up. He dropped the hoe at last, and Mama backed him all the way down the steep driveway to the dirt road. And he left, lumbering and swaying his way back home.

As I watched this scene, I felt like I was suffocating, as if someone had stuck a sack of cotton over my head. I'd heard Mama tell my father how Papa had beaten her as a child. When she was little and he got to drinking, one of his buddies would rush to the house to warn my grandmother that Papa was headed home. She'd hustle the four boys and my mother out of bed to make a run for the barn, hiding in the hay for the rest of the night. Other times, without warning, Papa barged into their bedrooms, hickory stick in hand, and the beatings began.

After that day, I still rode on top of Papa's wagon and helped him feed the cows and guinea hens, but I never trusted him again. I remember telling myself I'd better be careful about who I let myself love. It was likely they'd turn on you. I also realized it was a good idea to have a knife nearby whenever possible.

Not long after, Buzz disappeared. I figured he just wandered off. Thankfully, it never occurred to me then that Papa might have gotten his way after all.

Many years later, when I first started working at Goodyear, the union guys liked to tell the women that they were going to "pick" us. That is, they were going to catch us and pick each pubic hair from our bodies. Like so much that happened there, when you put it in words and see it on paper, it sounds too unreal to believe. But they were always up to some prank or another, often making work a dangerous sport.

One day, a woman worker, fed up with the constant haranguing, actually dropped her pants and dared the men to do it. With her pants bunched around her ankles, she stood there in her plain white underwear. The guys backed off her but kept up their nonsense with the rest of us. I knew I'd never do what she did, but I also knew they often made good on their word, one time pinning down one of the new young guys and picking him clean. I went home and found one of Charles's knives to carry in my pocket, the hard leather sheath resting against my thigh in case they ever decided to test me.

Countless times throughout the years at Goodyear when I needed courage, I remembered how Mama had finally tamed Papa that summer afternoon. I never doubted my mother would have used the butcher knife that day, and in my moments of fear and anger, I never doubted I'd use my own knife if necessary.

The place where I grew up during the 1940s is a small bend in the road along the foot of Choccolocco Mountain in northeast Alabama. Just like those pinch-faced gray possums that roamed the pine forests, the people in that small community in the foothills of the Appalachians knew a thing or two about survival. They worked in the cotton or steel mills or scratched a living from the dirt. Some worked in the foundries or the army depot in nearby Anniston or, if they were lucky, had a good-paying job at Goodyear in Gadsden. The folks I knew would walk over broken glass to help a neighbor and just as soon kill you if you did them wrong.

In 1946, I was in second grade when my father came home from the navy and my parents bought land from Papa to build a slightly bigger house across the road from him. Life started looking up for my family then. It took me a while to adjust to the gleam from the naked bulb hanging off the thin cord from the ceiling, since I'd been so used to the soft glow of gaslight. A couple of years later, we got indoor plumbing and things really changed for the better. Gone were the days of tiptoeing through the wet grass in the black of night, wondering if I'd step on a rattlesnake on the way to the outhouse.

Our new house wasn't much to look at, but we were lucky. We were the only ones in Possum Trot, besides the brick mason, who owned a television. Daddy worked the night shift at the Anniston Army Depot six days a week, where he reworked engines on the battered military tanks sent home from Korea and later from Vietnam and the Middle East. Before we bought the TV, in the evenings when Daddy was gone, Mama and I had nowhere to go and nothing to do--except for Saturday evening, when we turned on the radio, silent all week to save batteries, and listened to the Grand Ole Opry. But once we got the TV, folks gathered in every corner and doorway of our small house many evenings to watch the nightly news.

During the day, I had to come up with my own entertainment, and I ran wild, disappearing for hours to climb trees and explore the woods. My cousin Louise and I spent entire days searching for caves or hunting for arrowheads in the Indian cemetery. We also loved to mimic the holy dancing we saw at the church campground down the road.

Despite these wistful memories, nearly all of my childhood was spent in endless work. In the misty summer mornings Mama and I picked beans and okra before the sun started blazing down on us. After we headed back to the house to bathe and change, we spent the rest of the day hulling peas, skinning tomatoes, and blanching vegetables to can for the winter. We only stopped canning to sleep. On the weekends we roamed the woods to fill our syrup buckets with huckleberries and blackberries for jam and cobbler, slapping the itchy bites from the invisible chiggers with Listerine to keep them from driving us crazy.

Growing up, I never lacked for essentials, and I certainly never went hungry. I knew we were better off than a good many folks. Of course, I was also painfully aware that we weren't as well off as some others--like my best friend, Sandra. I'd known her since first grade. While I wore homemade bloomers, Sandra could afford silk panties. Every day she came to school in a coordinated sweater and skirt, never without a perfect strand of pearls. Even the teachers called her "little princess."

Sandra's family lived in New Liberty, a neighborhood where no one whitewashed their trees or kept chickens running around the front yard. There, children didn't have to share a bedroom with their grandmother, like I did. Sitting in front of the large mirror at Sandra's elegant dressing table, I'd angle her hand mirror every which way to see my reflection, hoping to improve my profile. But there it always was, clear as day, the bump in the middle of my nose, the same mysterious Indian nose as Granny Mac's and Daddy's.

Every time I came home from Sandra's, I felt inferior. Just the sight of my dingy white house and dusty dirt yard made me ashamed even though I knew how far we'd come. I dared not say anything about my disappointment. I saw how hard my parents worked. But the older I got, the more transparent the differences in my life and Sandra's became, and my sense of embarrassment stayed with me, as indelible as a birthmark. I was keenly aware that all this privilege was due to Goodyear, where Sandra's father worked. New Liberty was where the Goodyear families lived. And it's where, more than anywhere, I wanted to be.

I used to stare at the Goodyear plant when I passed it on my annual summer Greyhound bus trip to Aunt Mattie Bell and Uncle Hoyt's small duplex house in Gadsden. Right before you got into town, there was the plant, next to the Coosa River. A giant redbrick building with slits for windows, it sprawled for blocks behind a tall steel fence like a fortress. The huge smokestacks billowed black smoke. Riding past the plant, I dreamed about what it would have been like to ride around in a brand-new Mercury every few years like Sandra. Or I imagined swimming in the Gulf Coast during spring break like she did. I even fantasized about how smooth my hands would be if my daddy worked at Goodyear. Maybe even best of all, if he did, I'd never have to pick cotton again.

All my life I'd been surrounded by one continuous cotton field. I started picking cotton there before I entered first grade and had been picking ever since. It was the only job around, and I was in the field every weekend with my cousin Louise making extra money for the family. When I was older, during the summer Louise and I chopped cotton before it matured in order to earn some spending money of our own. We slung our hoes into the ground, attacking the johnsongrass that spread like gossip between the rows, sputtering complaints to each other that we dared not offer to anyone else. It wasn't just the cotton. When we picked corn, we bellyached the same way, row after row, as cornstalks slapped our bare necks and scratched our hands.

At the end of the day, two men shouldered a pole between them and hooked our sack of cotton onto the P ring as Papa--all six foot five of him--loomed above me and slid a heavy metal ball across the bar to determine how many pounds we'd plucked from the prickly stalks. It took days to fill our long, skinny sacks. Sometimes it felt like I was trying to fill the sack with clouds.

Recenzii

“Compelling...This story of a lifelong struggle for fairness deserves to be widely read not only as a document of a case so stunningly unjust that it sparked legislative change, but also as an introduction to a remarkable woman who also happens to be an outstanding storyteller .”

—Ms.

“Inspiring….Frank and feisty.”

-Kirkus

“A riveting and inspiring story of a true American hero from Possum Trot, Alabama, who in her own compelling voice tells the story of how she broke down barriers throughout her life, and in the process gave all women in this country the right to get equal pay. A must read.”

—Marcia Greenberger, Co-President, National Women’s Law Center