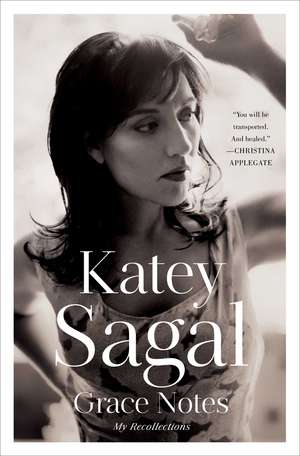

Grace Notes: My Recollections

Autor Katey Sagalen Limba Engleză Paperback – 15 noi 2017

In Grace Notes, Katey Sagal chronicles the rollercoaster ride of her life in this series of gorgeously wrought vignettes, resulting in a memoir unlike any other Hollywood memoir you’ve read before.

She takes you through the highs and lows of her life, from the tragic deaths of her parents to her long years in the Los Angeles rock scene, from being diagnosed with cancer at the age of twenty-eight to getting her big break on the fledgling FOX network as the wise-cracking Peggy Bundy on the beloved sitcom Married…with Children.

Sparse and poetic, Grace Notes is an emotionally riveting tale of struggle and success, both professional and personal: Sagal’s battle with sobriety; the still birth of her first daughter, Ruby; the challenges of maintaining a marriage with her second husband as he struggled with his own addiction; motherhood; the experience of having her third daughter at age fifty-two with the help of a surrogate; and her lifelong passion for music. Intimate, candid, and offering an inside look at the entertainment industry, Grace Notes offers unprecedented access to the previously unknown life of a woman whom audiences have loved for over thirty years.

Preț: 91.92 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 138

Preț estimativ în valută:

17.59€ • 19.12$ • 14.79£

17.59€ • 19.12$ • 14.79£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 29 martie-12 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781476796727

ISBN-10: 1476796726

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: B&W chapter openers

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

ISBN-10: 1476796726

Pagini: 256

Ilustrații: B&W chapter openers

Dimensiuni: 140 x 213 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Gallery Books

Colecția Gallery Books

Notă biografică

A versatile and award-winning actress, Katey Sagal is also a talented songwriter and singer. With over thirty years in show business, Katey has gained a legion of loyal fans who have followed her from Married…with Children, 8 Simple Rules, Futurama, to Sons of Anarchy, for which she won a Golden Globe. She currently resides in Los Angeles with her husband, three children, and two dogs. Follow her on Twitter @KateySagal.

Extras

Grace Notes

![]()

![]()

When I was ten, my mother taught me to play the guitar. We were living in the Westwood section of Los Angeles at the time. Dark and cavernous, the house seemed to me an enormous Spanish hacienda. (I went back years later, and it was more like a casita.) Mom and I sat in the living room, the dark wooden floors and rich red tiles providing the effect of an echo chamber. My mom, as always, was dressed in her simple way, with her hair cut in a short, unstuffy style that I understood later was meant to avoid adding complications to her life.

“Darling girl!” She called me to her. “Let me show you. This is what I did at your age.”

I sat on her lap, the guitar in mine, with her arms draped around me, and we picked and strummed in tandem, like one person. My hands hurt as I stretched and pressed my fingers into the strings. She rested her hands, bird-like and delicate, on top of mine and helped to mold my fingers into chord formations with one hand while strumming with the other. If I concentrate, I can still feel her small hands touching me. I was so much bigger than her, even as a little kid. She was happy then and suntanned, memorable because it was rare that she had color. She stayed inside so much of the time.

“Down in the Valley” was the first song I learned. A traditional folk ballad my mom played every time she picked up her guitar. We sang loudly. My hands wrapped around the wide neck of Mom’s maple-colored Martin. Her nylon string acoustic guitar, the one she was given by Burl Ives. I never really knew why or how she got his guitar; that’s one of the heartbreaks of having dead parents: no one to fill in the blanks.

“Down in the valley, valley so low, hang your head over, hear the wind blow . . .”

Kent cigarettes, butts and burning, in an ashtray nearby. The smell of slept-in clothes, dirty hair, and tobacco—the smells of my mom—filling the space along with the low, rich tones of her voice. A deep alto by this time in her life, she still sang with the faint twang of the yodeler she was in her younger years. Long ago, when my mother was eleven years old, she had her own fifteen-minute daily radio show out of Gaffney, South Carolina. She was known as “the Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County.”

I imagine Mom at eleven to have been hopeful and enthusiastic, full of promise and invigorated by life’s possibilities. But this Mom—the Mom at age thirty-five whom I sat with in our living room—her, not so much. This was years after the radio show. Much had happened in her life—and not happened.

By the time I was old enough to know my mom, she’d moved far beyond “the Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County” to a life of darkened rooms and hushed hallways, the house’s forced stillness when she had taken to her bed. The official diagnosis was heart disease, but I’ve always thought she had a broken heart.

Mom had started working young and would continue to do so in many different forms until she married. From the radio show at eleven in Gaffney, she was discovered by NBC Radio and sent to New York to continue her show. The family lore goes that my gambling granddad, Daniel, had left my grandmother for the racetrack one day and never returned. And with my mom footing the bill with her radio show paychecks, my grandma moved herself and four kids to the Big Apple. My mom helped to support them all, while Grandma Virginia found a job, went back to school, and eventually landed the position of the dean of women at Hunter College.

In her early twenties, during World War II, my mom entertained the troops overseas on tour with the USO and later appeared on Broadway. At some point, she moved to the other side of the line, got a gig working for Norman Lear on The Martin and Lewis Show as script supervisor, and in time became the first woman assistant director in live television. She also did her share of writing.

What I remember?

Rin Tin Tin comic books and several soap operas written under an alias.

My mom had plans, and hopes; more to say and create.

However, work came to a screeching standstill when she met my dad, a Russian cab driver by day with a theater degree and an ambition to direct. She loved him. She was twenty-five years old when in 1952 she tied the knot, an age considered borderline “over the hill.” And as was expected in her generation, she gave up her career and started making babies. My sense is that parenting paled in comparison with her dreams, and she was never really at home with her role as “Mom.”

I’m the oldest of five. Soon after her second baby was born, her life became filled with bouts of depression and the occasional suicide attempt. Searching for answers, there were medications and therapists, and eventually institutions, sanitariums, and shock treatments. Maybe my mom just needed a job! I always felt she was born in the wrong generation. Things were changing slowly for women during the 1950s and 1960s, but wife and mother was still the norm, and when she tried to do what was now expected of her, it broke her heart. All of the treatments in the world couldn’t make it okay. She felt silenced.

We were living in Encino, California, the first time my mom “went away,” and my grandma came to stay. With three kids—me, my brothers David and Joey—under the age of five, my mom was institutionalized for depression and treated the electroshock therapy way. My workaholic dad neither asked for nor knew how to handle my mom’s illness with much more than hysteria and more work.

So arrived my mom’s mom, Virginia Lee Zwilling. Alabama born, ladylike and soft-spoken, a true Southern matriarch, she knew how to bring calm in the midst of crazy.

“It’s gonna be aaalright, dahlin’, don’t you worry your pretty little head,” she’d say, standing solid.

No hurdle too high.

No waters too deep.

She was unshakeable.

Virginia Lee came into our lives as the wheels were comin’ off and stealthily did what needed to be done.

I have no recollection of my mom leaving for an extended stay.

There was no discussion of “vacation” or “visiting relatives.”

She was just gone.

I have no memory of my grandmother moving in.

She was just there.

As if she’d always been there.

Virginia Lee picked up the pieces more than once when Mom was “away.” With her chicken and dumplings and Bisquick biscuits, over the years she became my teacher of all things domestic.

Each visit, she would teach me a new household skill.

She taught me how to set a table and make bed “corners.” How to sew on a button, iron and fold the laundry, get a hot meal on the table.

How to write a check.

How to mix a martini.

She knew, for me to feel safe, I’d need to grow up quickly.

And I did.

I can hear her voice in my head. Like honey, that Southern drawl, letting me know I would need to be able to take care of myself.

I basked in her organized ways.

She calmed the chaos.

She straightened our squiggly lines and helped us make sense.

Compared with the harried, distracted, conflicted energy of my mother, trying to fit into her apron and housedress, fighting to stuff her artistic voice into the back of the closet with her working girl wardrobe, my grandma was a steady flow of calm waters. And clear direction.

I loved having her around.

* * *

Maybe those shock treatments are what broke my mom’s heart. She began going in for them in her early thirties—and then developed heart disease by the time she was thirty-five. Maybe those electroshocks made her arteries constrict, decreased her blood flow, and stunted the outpouring of happy endorphins.

From then on, she took a lot of pills. At a very early age, I was aware of pill bottles by my mom’s bed, always. She was forever swallowing pills. Some to help her sleep, some to thin her blood, small white nitro pills to explode open the blockages in her arteries, so she wouldn’t have a heart attack. Wherever she went, they went too. She even had bejeweled cases for her pills, for when she was out and about, even just for when she traveled from room to room. They dictated her days. They shut her eyes at night. They were consistent, and consoling, prescribed to keep her engine running.

My dad, a director, was usually at work before dawn, and my mom usually slept until noon. She’d put out boxes of cereal and Sara Lee coffee cakes the night before so we could have breakfast in the morning without waking her up. We didn’t even need bowls. My brothers and I cut along the perforations on those cute little cereal boxes, poured in our milk, and chowed down right from the box.

So breakfast was peaceful.

Dinner was often another story. My mom would sit at the dinner table, pill box at her side, and pop one, two, three, four, small, white nitro pills before, during, and most definitely after a meal. Just in case, and to protect her broken heart from breaking even further, as dinnertime sometimes went way beyond sharing a meal.

It’s when the scabs got ripped off. And my family let it fly.

Whatever had been brewing, festering, the air was let out of the balloon at dinnertime.

It was my mother’s intention to have these family dinners five nights a week. Usually by Wednesday, it would all go south.

“Don’t upset your mother,” Dad would say in a harsh whisper. “You’ll give her a heart attack.”

Emotions stuffed, burden lifted, we’d scatter.

Into our own little corners, our own quiet spaces, with our dinner on TV trays, and no mention of what had gone down at the table: who got yelled at the loudest, who left the table in hysterics, whose head fell in her plate as the family tried to act like everything was normal.

When we could manage a meal as a unit, my mom always had to sit for a time afterward to digest. She couldn’t jump up from the table and clear the dishes because she might have a heart attack. (Even now I wonder: Really?)

She had a buzzer put in under the table so she could remain seated, and someone would be buzzed to clear the dishes—a housekeeper, a nanny, a daughter—whoever was around. Because of the constant threat of heart attack.

I became accustomed to living on guard. Waiting for her to go down the rabbit hole. Waiting for the shit to hit. I became adept at coping with high hysterics, managing, rearranging, orchestrating, and waiting. Always waiting. I lived with a knot in my stomach.

It still knots up.

I often have to remind myself that I can let go of it now.

* * *

From day to day, I never knew which ailment Mom was struggling with.

And on some days, there was no ailment at all.

I’d almost have a “Mom” like everyone else’s Mom.

She’d be hustling and bustling, light and engaging, funny and consoling—concerned about us.

Just as I started to feel kid-like again, the change would always come.

She’d take to her bed.

The house would dim.

I couldn’t have friends over because “My mom’s sick.”

I couldn’t play too loud in the house because “My mom might have a heart attack.”

The drapes were drawn.

Wanting to be close, I’d sometimes get into bed with her; my head on a pillow, on her lap, as she stroked my hair.

“My darling girl,” she’d say. “I love you so.”

The nighttime was a good time for her. The middle of the night. I used to love to sit with my mom in our sunken living room in front of one of the six or seven individual-size TVs we had scattered around our house. I’d wake myself up on a school night just to be with her in the quiet great room, hunched over our small set, voices low and whispery, so as not to wake the rest. She was content late at night. Neither bleary eyed nor hysterical, she was even.

Even with what her life looked like.

Even with the sometimes disappearing, sporadically rageful presence that was my dad.

Even with the passage of time and the abandonment of her dreams and passions.

Even okay with that.

She was open and thoughtful.

Interested and sage after midnight.

Gave great advice, told wicked, funny stories, held me, stroked my hair, and told me how much she loved me.

And then sometimes . . .

Complained about my dad, wondered aloud if he was faithful, told me that she wanted to die. I held her, stroked her hair, and told her how much I loved her.

When she’d fall apart, I liked it, maybe even the best.

Those times when she’d splinter. The times I could tell she leaned on me, saying without saying, she really needed me to save her life. To give her hope.

Middle of the night was the time I felt I had her full attention.

My first music teacher, my mom was also my greatest artistic support system, and we discussed what music I should be listening to, what plays I should be reading, what movies were worth watching.

When I was in a school play or musical, she came to rehearsals and took notes.

When I wrote a new song, she listened enthusiastically and cheered me on.

She never once told me not to do what I wanted to do.

She had joy and enthusiasm for my creative pursuits, and I could intuit that my dreams were infusing her dimmed life force. Vicariously, she was breathing through me.

“You should go back to work, Mom,” I’d say. “Start writing again, even if it’s those dumb soap operas you used to ghostwrite. Just . . . something.”

There was always an excuse: always another child to raise, always another reason why that wasn’t a good idea—at least not just yet.

“Your father doesn’t really want me to,” she’d say.

But I think dissatisfaction had become her safe place.

My mom, always such a sad mystery to me. Shrouded in secrets, I never really knew what the fuck was in her head. I always felt there was more to the story. Shit I just kind of made up. Something she wasn’t telling me. Years later, I speculate.

But even then, as a teenager, I knew there was only so much I could do; that hers was a fragile life, and that it was only a matter of time before there would be an exit.

* * *

On the night my mother died, I went to the house in the early evening to visit or to pick up something—I can’t quite remember. I’d been living in Laurel Canyon for a few years at the time. I’d moved out at seventeen and came home infrequently. I hadn’t seen her in a while.

When I came into the house, she was there with my thirteen-year-old twin sisters, Liz and Jean, and they were on their way out to the movies. That seemed different to me, as did the fact that she seemed so happy. She looked beautiful and glad to see me.

“My darling girl!” she almost shrieked, wrapping me in her arms. “I’ve missed you.”

None of that “Why haven’t you called?” bullshit that other parents pulled, just pure joy at being in the same room with me. It was kind of over the top, really—not what I’d come to know of her. I figured time had passed, things with my dad had settled down, and with two of her five kids launched, she had more space for herself.

Her appearance was such a strong contrast with how she normally looked, that I took it all in.

How glowy and content she was.

How strong and healthy she looked, with color in her cheeks.

Hair washed. Makeup on.

That night would be her last.

She would never wake up again.

* * *

The next morning apparently started as usual. My little sisters waking, getting themselves breakfast, heading out the door, while Mom slept. That was nothing unusual. There was no need to knock on her door to say good-bye, no need to let her know they were leaving.

At two o’clock that afternoon, my sisters, arriving home from school, crept into my mom’s bedroom on tiptoe to gently wake her and found her dead in her bed. Cause of death: heart attack in her sleep due to arteriosclerosis.

Liz told me that Mom was covered with bruises.

There was vomit sprayed across the wall above her head.

Is that what happens when you die from a heart attack in your sleep?

I’m not sure.

* * *

“Please hurry and grow up, so I can die,” she used to tell my sisters.

“I can’t do this anymore, I wish I was dead” had become her memorable response to any upset, real or imagined.

I’d heard it a lot in my life.

I finally just started to agree with her.

“Do it already, Mom. You are so fucking miserable.”

I was fed up with all that sadness.

Suffocated by it.

She had tried to take her life, for real, twice.

That I know of.

Both times, I found her and made the calls.

Undermining my mother’s wishes.

Her cries of “Leave me alone!”

“Please, don’t tell your father!”

“Just let me be!”

I remember my twelve-year-old self watching as she was lifted into the ambulance.

Her eventual return home.

But I don’t remember any mention of it, from anyone, to me, ever again.

* * *

When she did die, Dr. Kadish, our family doctor, and one of the people who was closest to my mom, arrived within a very short time and ruled her death a heart attack.

No talk of suicide. He loved my mom. He wouldn’t have wanted to believe that. There was no autopsy. Zip the bag, shut the door, sign the paper—done.

Years later, I spoke to Dr. Kadish about my mother’s death, wondering about the cause, and there was never a shift in his story. Even more years later, I tried to find my mother’s medical records as a way into her history, only to be told that all records had been destroyed. They were past their expiration date.

I will never know 100 percent for sure how she met her end—and I suppose it doesn’t really matter. But it does explain, for me, that final evening before her passing. It helps me understand and give resonance to the joy I felt from her, and for her.

I sometimes imagine, if she had resolved herself to an exit plan, she could have and would have allowed herself the quiet contentment of a darkened movie theater with my sisters. She would have confidently driven them all out into the night, showed up in a public place without her usual anxiety, and enjoyed herself, knowing that later in the night, she would be successful at last.

Sad no more.

I wasn’t surprised my mother died so young.

I was kind of relieved.

For her.

The Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County

When I was ten, my mother taught me to play the guitar. We were living in the Westwood section of Los Angeles at the time. Dark and cavernous, the house seemed to me an enormous Spanish hacienda. (I went back years later, and it was more like a casita.) Mom and I sat in the living room, the dark wooden floors and rich red tiles providing the effect of an echo chamber. My mom, as always, was dressed in her simple way, with her hair cut in a short, unstuffy style that I understood later was meant to avoid adding complications to her life.

“Darling girl!” She called me to her. “Let me show you. This is what I did at your age.”

I sat on her lap, the guitar in mine, with her arms draped around me, and we picked and strummed in tandem, like one person. My hands hurt as I stretched and pressed my fingers into the strings. She rested her hands, bird-like and delicate, on top of mine and helped to mold my fingers into chord formations with one hand while strumming with the other. If I concentrate, I can still feel her small hands touching me. I was so much bigger than her, even as a little kid. She was happy then and suntanned, memorable because it was rare that she had color. She stayed inside so much of the time.

“Down in the Valley” was the first song I learned. A traditional folk ballad my mom played every time she picked up her guitar. We sang loudly. My hands wrapped around the wide neck of Mom’s maple-colored Martin. Her nylon string acoustic guitar, the one she was given by Burl Ives. I never really knew why or how she got his guitar; that’s one of the heartbreaks of having dead parents: no one to fill in the blanks.

“Down in the valley, valley so low, hang your head over, hear the wind blow . . .”

Kent cigarettes, butts and burning, in an ashtray nearby. The smell of slept-in clothes, dirty hair, and tobacco—the smells of my mom—filling the space along with the low, rich tones of her voice. A deep alto by this time in her life, she still sang with the faint twang of the yodeler she was in her younger years. Long ago, when my mother was eleven years old, she had her own fifteen-minute daily radio show out of Gaffney, South Carolina. She was known as “the Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County.”

I imagine Mom at eleven to have been hopeful and enthusiastic, full of promise and invigorated by life’s possibilities. But this Mom—the Mom at age thirty-five whom I sat with in our living room—her, not so much. This was years after the radio show. Much had happened in her life—and not happened.

By the time I was old enough to know my mom, she’d moved far beyond “the Singing Sweetheart of Cherokee County” to a life of darkened rooms and hushed hallways, the house’s forced stillness when she had taken to her bed. The official diagnosis was heart disease, but I’ve always thought she had a broken heart.

Mom had started working young and would continue to do so in many different forms until she married. From the radio show at eleven in Gaffney, she was discovered by NBC Radio and sent to New York to continue her show. The family lore goes that my gambling granddad, Daniel, had left my grandmother for the racetrack one day and never returned. And with my mom footing the bill with her radio show paychecks, my grandma moved herself and four kids to the Big Apple. My mom helped to support them all, while Grandma Virginia found a job, went back to school, and eventually landed the position of the dean of women at Hunter College.

In her early twenties, during World War II, my mom entertained the troops overseas on tour with the USO and later appeared on Broadway. At some point, she moved to the other side of the line, got a gig working for Norman Lear on The Martin and Lewis Show as script supervisor, and in time became the first woman assistant director in live television. She also did her share of writing.

What I remember?

Rin Tin Tin comic books and several soap operas written under an alias.

My mom had plans, and hopes; more to say and create.

However, work came to a screeching standstill when she met my dad, a Russian cab driver by day with a theater degree and an ambition to direct. She loved him. She was twenty-five years old when in 1952 she tied the knot, an age considered borderline “over the hill.” And as was expected in her generation, she gave up her career and started making babies. My sense is that parenting paled in comparison with her dreams, and she was never really at home with her role as “Mom.”

I’m the oldest of five. Soon after her second baby was born, her life became filled with bouts of depression and the occasional suicide attempt. Searching for answers, there were medications and therapists, and eventually institutions, sanitariums, and shock treatments. Maybe my mom just needed a job! I always felt she was born in the wrong generation. Things were changing slowly for women during the 1950s and 1960s, but wife and mother was still the norm, and when she tried to do what was now expected of her, it broke her heart. All of the treatments in the world couldn’t make it okay. She felt silenced.

We were living in Encino, California, the first time my mom “went away,” and my grandma came to stay. With three kids—me, my brothers David and Joey—under the age of five, my mom was institutionalized for depression and treated the electroshock therapy way. My workaholic dad neither asked for nor knew how to handle my mom’s illness with much more than hysteria and more work.

So arrived my mom’s mom, Virginia Lee Zwilling. Alabama born, ladylike and soft-spoken, a true Southern matriarch, she knew how to bring calm in the midst of crazy.

“It’s gonna be aaalright, dahlin’, don’t you worry your pretty little head,” she’d say, standing solid.

No hurdle too high.

No waters too deep.

She was unshakeable.

Virginia Lee came into our lives as the wheels were comin’ off and stealthily did what needed to be done.

I have no recollection of my mom leaving for an extended stay.

There was no discussion of “vacation” or “visiting relatives.”

She was just gone.

I have no memory of my grandmother moving in.

She was just there.

As if she’d always been there.

Virginia Lee picked up the pieces more than once when Mom was “away.” With her chicken and dumplings and Bisquick biscuits, over the years she became my teacher of all things domestic.

Each visit, she would teach me a new household skill.

She taught me how to set a table and make bed “corners.” How to sew on a button, iron and fold the laundry, get a hot meal on the table.

How to write a check.

How to mix a martini.

She knew, for me to feel safe, I’d need to grow up quickly.

And I did.

I can hear her voice in my head. Like honey, that Southern drawl, letting me know I would need to be able to take care of myself.

I basked in her organized ways.

She calmed the chaos.

She straightened our squiggly lines and helped us make sense.

Compared with the harried, distracted, conflicted energy of my mother, trying to fit into her apron and housedress, fighting to stuff her artistic voice into the back of the closet with her working girl wardrobe, my grandma was a steady flow of calm waters. And clear direction.

I loved having her around.

* * *

Maybe those shock treatments are what broke my mom’s heart. She began going in for them in her early thirties—and then developed heart disease by the time she was thirty-five. Maybe those electroshocks made her arteries constrict, decreased her blood flow, and stunted the outpouring of happy endorphins.

From then on, she took a lot of pills. At a very early age, I was aware of pill bottles by my mom’s bed, always. She was forever swallowing pills. Some to help her sleep, some to thin her blood, small white nitro pills to explode open the blockages in her arteries, so she wouldn’t have a heart attack. Wherever she went, they went too. She even had bejeweled cases for her pills, for when she was out and about, even just for when she traveled from room to room. They dictated her days. They shut her eyes at night. They were consistent, and consoling, prescribed to keep her engine running.

My dad, a director, was usually at work before dawn, and my mom usually slept until noon. She’d put out boxes of cereal and Sara Lee coffee cakes the night before so we could have breakfast in the morning without waking her up. We didn’t even need bowls. My brothers and I cut along the perforations on those cute little cereal boxes, poured in our milk, and chowed down right from the box.

So breakfast was peaceful.

Dinner was often another story. My mom would sit at the dinner table, pill box at her side, and pop one, two, three, four, small, white nitro pills before, during, and most definitely after a meal. Just in case, and to protect her broken heart from breaking even further, as dinnertime sometimes went way beyond sharing a meal.

It’s when the scabs got ripped off. And my family let it fly.

Whatever had been brewing, festering, the air was let out of the balloon at dinnertime.

It was my mother’s intention to have these family dinners five nights a week. Usually by Wednesday, it would all go south.

“Don’t upset your mother,” Dad would say in a harsh whisper. “You’ll give her a heart attack.”

Emotions stuffed, burden lifted, we’d scatter.

Into our own little corners, our own quiet spaces, with our dinner on TV trays, and no mention of what had gone down at the table: who got yelled at the loudest, who left the table in hysterics, whose head fell in her plate as the family tried to act like everything was normal.

When we could manage a meal as a unit, my mom always had to sit for a time afterward to digest. She couldn’t jump up from the table and clear the dishes because she might have a heart attack. (Even now I wonder: Really?)

She had a buzzer put in under the table so she could remain seated, and someone would be buzzed to clear the dishes—a housekeeper, a nanny, a daughter—whoever was around. Because of the constant threat of heart attack.

I became accustomed to living on guard. Waiting for her to go down the rabbit hole. Waiting for the shit to hit. I became adept at coping with high hysterics, managing, rearranging, orchestrating, and waiting. Always waiting. I lived with a knot in my stomach.

It still knots up.

I often have to remind myself that I can let go of it now.

* * *

From day to day, I never knew which ailment Mom was struggling with.

And on some days, there was no ailment at all.

I’d almost have a “Mom” like everyone else’s Mom.

She’d be hustling and bustling, light and engaging, funny and consoling—concerned about us.

Just as I started to feel kid-like again, the change would always come.

She’d take to her bed.

The house would dim.

I couldn’t have friends over because “My mom’s sick.”

I couldn’t play too loud in the house because “My mom might have a heart attack.”

The drapes were drawn.

Wanting to be close, I’d sometimes get into bed with her; my head on a pillow, on her lap, as she stroked my hair.

“My darling girl,” she’d say. “I love you so.”

The nighttime was a good time for her. The middle of the night. I used to love to sit with my mom in our sunken living room in front of one of the six or seven individual-size TVs we had scattered around our house. I’d wake myself up on a school night just to be with her in the quiet great room, hunched over our small set, voices low and whispery, so as not to wake the rest. She was content late at night. Neither bleary eyed nor hysterical, she was even.

Even with what her life looked like.

Even with the sometimes disappearing, sporadically rageful presence that was my dad.

Even with the passage of time and the abandonment of her dreams and passions.

Even okay with that.

She was open and thoughtful.

Interested and sage after midnight.

Gave great advice, told wicked, funny stories, held me, stroked my hair, and told me how much she loved me.

And then sometimes . . .

Complained about my dad, wondered aloud if he was faithful, told me that she wanted to die. I held her, stroked her hair, and told her how much I loved her.

When she’d fall apart, I liked it, maybe even the best.

Those times when she’d splinter. The times I could tell she leaned on me, saying without saying, she really needed me to save her life. To give her hope.

Middle of the night was the time I felt I had her full attention.

My first music teacher, my mom was also my greatest artistic support system, and we discussed what music I should be listening to, what plays I should be reading, what movies were worth watching.

When I was in a school play or musical, she came to rehearsals and took notes.

When I wrote a new song, she listened enthusiastically and cheered me on.

She never once told me not to do what I wanted to do.

She had joy and enthusiasm for my creative pursuits, and I could intuit that my dreams were infusing her dimmed life force. Vicariously, she was breathing through me.

“You should go back to work, Mom,” I’d say. “Start writing again, even if it’s those dumb soap operas you used to ghostwrite. Just . . . something.”

There was always an excuse: always another child to raise, always another reason why that wasn’t a good idea—at least not just yet.

“Your father doesn’t really want me to,” she’d say.

But I think dissatisfaction had become her safe place.

My mom, always such a sad mystery to me. Shrouded in secrets, I never really knew what the fuck was in her head. I always felt there was more to the story. Shit I just kind of made up. Something she wasn’t telling me. Years later, I speculate.

But even then, as a teenager, I knew there was only so much I could do; that hers was a fragile life, and that it was only a matter of time before there would be an exit.

* * *

On the night my mother died, I went to the house in the early evening to visit or to pick up something—I can’t quite remember. I’d been living in Laurel Canyon for a few years at the time. I’d moved out at seventeen and came home infrequently. I hadn’t seen her in a while.

When I came into the house, she was there with my thirteen-year-old twin sisters, Liz and Jean, and they were on their way out to the movies. That seemed different to me, as did the fact that she seemed so happy. She looked beautiful and glad to see me.

“My darling girl!” she almost shrieked, wrapping me in her arms. “I’ve missed you.”

None of that “Why haven’t you called?” bullshit that other parents pulled, just pure joy at being in the same room with me. It was kind of over the top, really—not what I’d come to know of her. I figured time had passed, things with my dad had settled down, and with two of her five kids launched, she had more space for herself.

Her appearance was such a strong contrast with how she normally looked, that I took it all in.

How glowy and content she was.

How strong and healthy she looked, with color in her cheeks.

Hair washed. Makeup on.

That night would be her last.

She would never wake up again.

* * *

The next morning apparently started as usual. My little sisters waking, getting themselves breakfast, heading out the door, while Mom slept. That was nothing unusual. There was no need to knock on her door to say good-bye, no need to let her know they were leaving.

At two o’clock that afternoon, my sisters, arriving home from school, crept into my mom’s bedroom on tiptoe to gently wake her and found her dead in her bed. Cause of death: heart attack in her sleep due to arteriosclerosis.

Liz told me that Mom was covered with bruises.

There was vomit sprayed across the wall above her head.

Is that what happens when you die from a heart attack in your sleep?

I’m not sure.

* * *

“Please hurry and grow up, so I can die,” she used to tell my sisters.

“I can’t do this anymore, I wish I was dead” had become her memorable response to any upset, real or imagined.

I’d heard it a lot in my life.

I finally just started to agree with her.

“Do it already, Mom. You are so fucking miserable.”

I was fed up with all that sadness.

Suffocated by it.

She had tried to take her life, for real, twice.

That I know of.

Both times, I found her and made the calls.

Undermining my mother’s wishes.

Her cries of “Leave me alone!”

“Please, don’t tell your father!”

“Just let me be!”

I remember my twelve-year-old self watching as she was lifted into the ambulance.

Her eventual return home.

But I don’t remember any mention of it, from anyone, to me, ever again.

* * *

When she did die, Dr. Kadish, our family doctor, and one of the people who was closest to my mom, arrived within a very short time and ruled her death a heart attack.

No talk of suicide. He loved my mom. He wouldn’t have wanted to believe that. There was no autopsy. Zip the bag, shut the door, sign the paper—done.

Years later, I spoke to Dr. Kadish about my mother’s death, wondering about the cause, and there was never a shift in his story. Even more years later, I tried to find my mother’s medical records as a way into her history, only to be told that all records had been destroyed. They were past their expiration date.

I will never know 100 percent for sure how she met her end—and I suppose it doesn’t really matter. But it does explain, for me, that final evening before her passing. It helps me understand and give resonance to the joy I felt from her, and for her.

I sometimes imagine, if she had resolved herself to an exit plan, she could have and would have allowed herself the quiet contentment of a darkened movie theater with my sisters. She would have confidently driven them all out into the night, showed up in a public place without her usual anxiety, and enjoyed herself, knowing that later in the night, she would be successful at last.

Sad no more.

I wasn’t surprised my mother died so young.

I was kind of relieved.

For her.

Descriere

Award-winning actress and talented singer/songwriter Katey Sagal crafts an evocative and gripping memoir told in essays—perfect for fans of Patti Smith’s M Train.