Guns Up!: A Firsthand Account of the Vietnam War

Autor Johnnie M. Clark, Copyright Paperback Collectionen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 2001

"Guns up!" was the battle cry that sent machine gunners racing forward with their M60s to mow down the enemy, hoping that this wasn't the day they would meet their deaths. Marine Johnnie Clark heard that the life expectancy of a machine gunner in Vietnam was seven to ten seconds after a firefight began. Johnnie was only eighteen when he got there, at the height of the bloody Tet Offensive at Hue, and he quickly realized the grim statistic held a chilling truth.

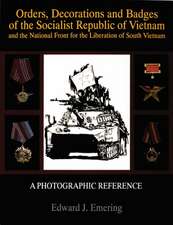

The Marines who fought and bled and died were ordinary men, many still teenagers, but the selfless bravery they showed day after day in a nightmarish jungle war made them true heroes. This new edition of Guns Up!, filled with photographs and updated information about those harrowing battles, also contains the real names of these extraordinary warriors and details of their lives after the war. The book's continuing success is a tribute to the raw courage and sacrifice of the United States Marines.

Preț: 55.61 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 83

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.64€ • 11.11$ • 8.81£

10.64€ • 11.11$ • 8.81£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 14-28 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345450265

ISBN-10: 0345450264

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 108 x 174 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Ediția:Rev

Editura: Presidio Press

ISBN-10: 0345450264

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 108 x 174 x 26 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Ediția:Rev

Editura: Presidio Press

Extras

WELCOME TO THE FIFTH MARINES AND THE BATTLE FOR TRUOI BRIDGE

The one comforting thought was that I wasn’t alone. The plane bulged with young Marine Corps faces. Private First Class Richard Chan was the only one I knew very well. We had been together since Parris Island, the Marine Corps boot camp.

Chan had been born in Red China. His father and mother smuggled him out as an infant. He wasn’t your average Marine. Besides being Chinese-American, he had his pre-med degree from the University of Tennessee with a minor in ministry. He could have been playing doctor in New York, but he joined the Corps because he felt that he owed the country a debt for taking him in. Corny as it might sound, he also wanted to be the best, a Marine, a feeling we all shared.

We couldn’t get away from each other. Bunkies at Parris Island, bunkies at ITR (Infantry Training Regiment) School, bunkies at jungle warfare school in Camp Pendleton, California. Now we sat beside each other on a plane landing in Da Nang.

The blistering sun stung my eyes as I reached the first step of the drab gray departing ramp. I tried to be ready to duck. Scuttlebutt had it that one planeload of Marines had gotten hit on the runway, but I couldn’t hear any gunshots, just some moronic sergeant screaming, “Move it! Move it! Move it!” By the time I reached the bottom of the ramp, my eyes adjusted enough to see a hot blue sky without a single cloud. A sleek, impressive camouflaged Phantom jet whined to a stop nearby. Thundering artillery echoed across the airstrip. The Marine in front of me whistled. “Man! They mean business.” God, I thought, this is the real thing. I’m in a war. I mumbled a quick prayer, something I hadn’t done since I was fourteen.

A skinny-looking helicopter floated down one hundred meters to our right. Its camouflaged body bristled with rockets and machine guns. The roar of another camouflaged Phantom streaking down a runway snatched my eyes as it sprang off the ground and climbed sharply above the steep green mountains surrounding Da Nang.

We double-timed over to a processing area. It was a couple of hundred yards away, but by the time we stopped, I was dripping wet. The pilot of the Braniff had said it was 119 degrees. I’d thought he’d been joking.

The Tet Offensive was in full swing, and the battle for Hue City had covered the front page of every newspaper back home. On TV the house-to-house fighting looked like World War II films.

Chan stood in front of me in the alphabetical line of Marines filing past a loud dispersing officer. Each man handed him a set of orders which he grabbed quickly and stamped with a big rubber stamp as he screamed, “Fifth Marines!” I tapped Chan on the shoulder.

“Why’s everybody going to the Fifth Marines? They can’t need this many replacements.”

Chan looked over his shoulder with one of those “Boy have I got news for you” looks. “Oh, I think they might have accommodations for us. That’s the regiment that’s taking Hue City.”

“Thanks, buddy,” I said with a hard slap on his back. “I can always depend on you to find a bright spot in all this.”

“Move it! Move it! Move it!” shouted the sergeant.

A moment later the big rubber stamp came down on my orders like the authority of God. “Fifth Marines!”

We marched to a large dusty tent that was surrounded by a four-foot wall of sandbags. As a darkly tanned corporal called out names, each man stepped into the tent. Inside, a corporal with a huge black mustache handed me an M16 rifle, five magazines, and two bandoliers of ammunition. One of the men got a rifle with a bullet hole through the stock. When they gave the same guy a helmet with a bullet crease on the side, he nearly came unraveled.

Twenty minutes later we were herded into a waiting C-130 for a short flight north to a place called Phu Bai. The flight would have been more comfortable with seats or windows and without rifles sticking in my ear. One guy said we were flying over the South China Sea to avoid potshots. I wanted to be mentally ready for people shooting at me, but I could tell already there was a fine line between ready and panic.

Phu Bai was the base camp for the Fifth Marines. It didn’t look like a dangerous place. One part even looked fairly civilized, with groups of tin-roofed houses made of wood and screen. Sandbag bunkers dotted the camp, and everything was colored beige over green from the dust of tanks, trucks, and jeeps rolling through the dirt streets. I soon found out that the civilized part of Phu Bai belonged to the Army. The Marine area was all tents. As usual, the Army was equipped far better than the Corps—a constant source of irritation to Marines.

Phu Bai sat fifteen miles from Hue City. Just a quick truck ride north on Highway 1 would take me to Hue. Another little longer ride would take me to a place called Khe Sanh.

We were taken to a large tent where an old, crusty-looking master gunnery sergeant with a giant silver handle- bar mustache screamed, “Attention!” The chattering tent went silent.

“I am Master Gunnery Sergeant O’Connel. I will help you in your indoctrination on the Fifth Marine Regiment.” The old sergeant gave his great mustache a slow proud twirl and turned to a large blackboard behind him. “This is the most decorated regiment in the United States Marine Corps.” He spoke as he wrote “French Forteget” at the top of the blackboard. “Some of you may remember hearing about the Belleau Woods in boot camp. The Fifth took the woods in twenty-four hours of hand-to-hand combat. You will wear on your dress uniform the French Forteget. We are the only Marines in the Corps allowed to wear any item other than Marine Corps issue. The Fifth Marines have taken Guadalcanal; New Guinea; New Britain; Peleiu; Okinawa; Tientsin, China; Pusan; Inchon, in Seoul, Korea; and the Chosin Reservoir. Now it’s Hue City.” He put his hands on his hips, standing with his boots more than shoulder-width apart. He beamed with pride as he stuck out his barrel-shaped chest. “We have the highest kill ratio in Vietnam. The colonel does not intend for that to change. Unless we are given permission to invade the North we shall continue fighting under the rules now in effect. You will not kill people who are not in uniform unless you are fired upon by them. You will kill anyone in a North Vietnamese Government . . .”

As the indoctrination continued I became more confused. I wasn’t sure if this guy was saying this crap because it was procedure or if we were really supposed to wait to be fired upon before returning fire.

Thoughts of all kinds scrambled through my mind like a blender. I felt scared and excited and lonely at the same instant, but mostly excited. I couldn’t wait to write the first letter home and tell everyone all about it. I didn’t know a bloody thing about it yet, but I knew I had to keep a few girls worried to make sure I got a lot of mail.

After the indoctrination, we were led to a small firing range where we got a chance to make sure our weapons worked, a small item I hadn’t given a thought to.

A sunburned sergeant began shouting. “The first ten in column spread out facing the targets at the ready position. Feet spread! Rifles at the ready! Move it! Count off!”

“Nine!” I shouted as my turn came to jog into a position facing ten large black-and-white bull’s-eyes staked to the side of a fifty-foot-long by ten-foot-tall mound of dirt. The targets looked about one hundred meters away, just inside the barbed-wire perimeter surrounding Phu Bai.

“Lock and load!” I checked my magazine and flicked my rifle off safety.

“Step two of the prone position! Drop to the knees holding rifle securely! Drop to your stomach breaking your fall with the butt of the rifle!” I dropped to my stomach and took aim at the bull’s-eye straight ahead.

“Aim and fire!” shouted the sergeant, and I did. Nothing! I squeezed the trigger again. My weapon sent out a harmless klick amidst the continuous firing from the other nine rifles. My stomach churned as I looked past the targets to the unfriendly mountains beyond.

The sergeant quickly found me a rifle that worked, but the broken firing pin left me with serious doubts. “Check your boots,” my stomach said.

Now that my confidence was thoroughly shaken we were led back to a row of large dusty tents. A voice shouted to get in a formation, so we did. A truckload of Marines drove by, covering us with a solid layer of dust. The men in the truck howled with laughter at us. Some shouted friendly insults about our stateside utilities. We stuck out like big green thumbs. Every person we’d seen so far was dressed in jungle utilities. The men in the truck looked hard. Their jungle clothes were tattered and torn. The men hadn’t shaved in a long time, their skin was dark from the jungle sun, and they looked lean and mean like Marines are supposed to look. We looked like fat, happy kids, clean-shaven, with side-walled haircuts and spit-shined stateside boots.

A small snappy corporal began shouting our names in alphabetical order. Once we were all accounted for, we filed into the first in the long row of tents. Once inside, a tough-looking supply sergeant shouted at me, “What’s your size, Marine?” Like everyone else, I received a flak jacket, cartridge belt, canteens, four grenades, one pack, jungle boots, and utilities. After that we were led to different tents according to the platoons and companies we had been assigned. Unbelievably, Chan and I were together again—same company, same platoon.

Inside our tent were two rows of cots. At the end of one row, dwarfing the small cot he slept on, rested a giant red-headed man. His arms looked as big as my legs, and he must have had on size fifteen boots, which, like his utilities, were bleached beige from the sun and rain. They looked molded to his feet as if they were moccasins he hadn’t taken off for years.

I wanted to talk about this adventure with him right now. Chan must have thought the same thing. We walked to the end of the tent and sat side by side on the cot next to him. I wasn’t sure what he might think, since the rest of the tent was empty. It reminded me of standing at the end of a row of twenty unoccupied urinals and having one guy walk in and take the one right next to me.

He looked like a giant Viking. A big red mustache matched his hair. He was the most handsome red-headed man I’d ever seen. A real billboard Marine. I leaned closer to tap him on the shoulder. As he rolled over, the cot creaked under the strain. I knew one thing for sure: I wanted this monster on my side when the fighting started. He opened one large blue eye, which focused in on Chan.

“What’s this gook doing in here?”

Chan jumped to his feet. He rambled off a series of insults, some of which included the biological background of the big redhead’s parents, his speech, his looks, his smell, and his intelligence.

The one comforting thought was that I wasn’t alone. The plane bulged with young Marine Corps faces. Private First Class Richard Chan was the only one I knew very well. We had been together since Parris Island, the Marine Corps boot camp.

Chan had been born in Red China. His father and mother smuggled him out as an infant. He wasn’t your average Marine. Besides being Chinese-American, he had his pre-med degree from the University of Tennessee with a minor in ministry. He could have been playing doctor in New York, but he joined the Corps because he felt that he owed the country a debt for taking him in. Corny as it might sound, he also wanted to be the best, a Marine, a feeling we all shared.

We couldn’t get away from each other. Bunkies at Parris Island, bunkies at ITR (Infantry Training Regiment) School, bunkies at jungle warfare school in Camp Pendleton, California. Now we sat beside each other on a plane landing in Da Nang.

The blistering sun stung my eyes as I reached the first step of the drab gray departing ramp. I tried to be ready to duck. Scuttlebutt had it that one planeload of Marines had gotten hit on the runway, but I couldn’t hear any gunshots, just some moronic sergeant screaming, “Move it! Move it! Move it!” By the time I reached the bottom of the ramp, my eyes adjusted enough to see a hot blue sky without a single cloud. A sleek, impressive camouflaged Phantom jet whined to a stop nearby. Thundering artillery echoed across the airstrip. The Marine in front of me whistled. “Man! They mean business.” God, I thought, this is the real thing. I’m in a war. I mumbled a quick prayer, something I hadn’t done since I was fourteen.

A skinny-looking helicopter floated down one hundred meters to our right. Its camouflaged body bristled with rockets and machine guns. The roar of another camouflaged Phantom streaking down a runway snatched my eyes as it sprang off the ground and climbed sharply above the steep green mountains surrounding Da Nang.

We double-timed over to a processing area. It was a couple of hundred yards away, but by the time we stopped, I was dripping wet. The pilot of the Braniff had said it was 119 degrees. I’d thought he’d been joking.

The Tet Offensive was in full swing, and the battle for Hue City had covered the front page of every newspaper back home. On TV the house-to-house fighting looked like World War II films.

Chan stood in front of me in the alphabetical line of Marines filing past a loud dispersing officer. Each man handed him a set of orders which he grabbed quickly and stamped with a big rubber stamp as he screamed, “Fifth Marines!” I tapped Chan on the shoulder.

“Why’s everybody going to the Fifth Marines? They can’t need this many replacements.”

Chan looked over his shoulder with one of those “Boy have I got news for you” looks. “Oh, I think they might have accommodations for us. That’s the regiment that’s taking Hue City.”

“Thanks, buddy,” I said with a hard slap on his back. “I can always depend on you to find a bright spot in all this.”

“Move it! Move it! Move it!” shouted the sergeant.

A moment later the big rubber stamp came down on my orders like the authority of God. “Fifth Marines!”

We marched to a large dusty tent that was surrounded by a four-foot wall of sandbags. As a darkly tanned corporal called out names, each man stepped into the tent. Inside, a corporal with a huge black mustache handed me an M16 rifle, five magazines, and two bandoliers of ammunition. One of the men got a rifle with a bullet hole through the stock. When they gave the same guy a helmet with a bullet crease on the side, he nearly came unraveled.

Twenty minutes later we were herded into a waiting C-130 for a short flight north to a place called Phu Bai. The flight would have been more comfortable with seats or windows and without rifles sticking in my ear. One guy said we were flying over the South China Sea to avoid potshots. I wanted to be mentally ready for people shooting at me, but I could tell already there was a fine line between ready and panic.

Phu Bai was the base camp for the Fifth Marines. It didn’t look like a dangerous place. One part even looked fairly civilized, with groups of tin-roofed houses made of wood and screen. Sandbag bunkers dotted the camp, and everything was colored beige over green from the dust of tanks, trucks, and jeeps rolling through the dirt streets. I soon found out that the civilized part of Phu Bai belonged to the Army. The Marine area was all tents. As usual, the Army was equipped far better than the Corps—a constant source of irritation to Marines.

Phu Bai sat fifteen miles from Hue City. Just a quick truck ride north on Highway 1 would take me to Hue. Another little longer ride would take me to a place called Khe Sanh.

We were taken to a large tent where an old, crusty-looking master gunnery sergeant with a giant silver handle- bar mustache screamed, “Attention!” The chattering tent went silent.

“I am Master Gunnery Sergeant O’Connel. I will help you in your indoctrination on the Fifth Marine Regiment.” The old sergeant gave his great mustache a slow proud twirl and turned to a large blackboard behind him. “This is the most decorated regiment in the United States Marine Corps.” He spoke as he wrote “French Forteget” at the top of the blackboard. “Some of you may remember hearing about the Belleau Woods in boot camp. The Fifth took the woods in twenty-four hours of hand-to-hand combat. You will wear on your dress uniform the French Forteget. We are the only Marines in the Corps allowed to wear any item other than Marine Corps issue. The Fifth Marines have taken Guadalcanal; New Guinea; New Britain; Peleiu; Okinawa; Tientsin, China; Pusan; Inchon, in Seoul, Korea; and the Chosin Reservoir. Now it’s Hue City.” He put his hands on his hips, standing with his boots more than shoulder-width apart. He beamed with pride as he stuck out his barrel-shaped chest. “We have the highest kill ratio in Vietnam. The colonel does not intend for that to change. Unless we are given permission to invade the North we shall continue fighting under the rules now in effect. You will not kill people who are not in uniform unless you are fired upon by them. You will kill anyone in a North Vietnamese Government . . .”

As the indoctrination continued I became more confused. I wasn’t sure if this guy was saying this crap because it was procedure or if we were really supposed to wait to be fired upon before returning fire.

Thoughts of all kinds scrambled through my mind like a blender. I felt scared and excited and lonely at the same instant, but mostly excited. I couldn’t wait to write the first letter home and tell everyone all about it. I didn’t know a bloody thing about it yet, but I knew I had to keep a few girls worried to make sure I got a lot of mail.

After the indoctrination, we were led to a small firing range where we got a chance to make sure our weapons worked, a small item I hadn’t given a thought to.

A sunburned sergeant began shouting. “The first ten in column spread out facing the targets at the ready position. Feet spread! Rifles at the ready! Move it! Count off!”

“Nine!” I shouted as my turn came to jog into a position facing ten large black-and-white bull’s-eyes staked to the side of a fifty-foot-long by ten-foot-tall mound of dirt. The targets looked about one hundred meters away, just inside the barbed-wire perimeter surrounding Phu Bai.

“Lock and load!” I checked my magazine and flicked my rifle off safety.

“Step two of the prone position! Drop to the knees holding rifle securely! Drop to your stomach breaking your fall with the butt of the rifle!” I dropped to my stomach and took aim at the bull’s-eye straight ahead.

“Aim and fire!” shouted the sergeant, and I did. Nothing! I squeezed the trigger again. My weapon sent out a harmless klick amidst the continuous firing from the other nine rifles. My stomach churned as I looked past the targets to the unfriendly mountains beyond.

The sergeant quickly found me a rifle that worked, but the broken firing pin left me with serious doubts. “Check your boots,” my stomach said.

Now that my confidence was thoroughly shaken we were led back to a row of large dusty tents. A voice shouted to get in a formation, so we did. A truckload of Marines drove by, covering us with a solid layer of dust. The men in the truck howled with laughter at us. Some shouted friendly insults about our stateside utilities. We stuck out like big green thumbs. Every person we’d seen so far was dressed in jungle utilities. The men in the truck looked hard. Their jungle clothes were tattered and torn. The men hadn’t shaved in a long time, their skin was dark from the jungle sun, and they looked lean and mean like Marines are supposed to look. We looked like fat, happy kids, clean-shaven, with side-walled haircuts and spit-shined stateside boots.

A small snappy corporal began shouting our names in alphabetical order. Once we were all accounted for, we filed into the first in the long row of tents. Once inside, a tough-looking supply sergeant shouted at me, “What’s your size, Marine?” Like everyone else, I received a flak jacket, cartridge belt, canteens, four grenades, one pack, jungle boots, and utilities. After that we were led to different tents according to the platoons and companies we had been assigned. Unbelievably, Chan and I were together again—same company, same platoon.

Inside our tent were two rows of cots. At the end of one row, dwarfing the small cot he slept on, rested a giant red-headed man. His arms looked as big as my legs, and he must have had on size fifteen boots, which, like his utilities, were bleached beige from the sun and rain. They looked molded to his feet as if they were moccasins he hadn’t taken off for years.

I wanted to talk about this adventure with him right now. Chan must have thought the same thing. We walked to the end of the tent and sat side by side on the cot next to him. I wasn’t sure what he might think, since the rest of the tent was empty. It reminded me of standing at the end of a row of twenty unoccupied urinals and having one guy walk in and take the one right next to me.

He looked like a giant Viking. A big red mustache matched his hair. He was the most handsome red-headed man I’d ever seen. A real billboard Marine. I leaned closer to tap him on the shoulder. As he rolled over, the cot creaked under the strain. I knew one thing for sure: I wanted this monster on my side when the fighting started. He opened one large blue eye, which focused in on Chan.

“What’s this gook doing in here?”

Chan jumped to his feet. He rambled off a series of insults, some of which included the biological background of the big redhead’s parents, his speech, his looks, his smell, and his intelligence.

Notă biografică

Johnnie M. Clark is a disabled veteran who lives with his wife and two children in St. Petersburg, Florida. After joining the Marine Corps at age seventeen, he served as a machine gunner with the famous 5th Marine Regiment in 1968 and was wounded three times. He was awarded the Silver Star for bravery. While recuperating in Okinawa, Mr. Clark studied karate as part of his rehabilitation program, and after his discharge, he taught martial arts at the University of South Florida. He is now a 6th Dan Master of tae kwan do and operates a tae kwan do school in St. Petersburg. Clark is also the author of Semper Fidelis, The Old Corps, No Better Way to Die, and the forthcoming Harlot's Cup. He is the recipient of the Brig. Gen. Robert L. Denig Memorial Distinguished Service Award for writing.

Descriere

Considered one of the all time classic memoirs of combat during the Vietnam War, "Guns Up!" is now updated. Only an 18-year-old Marine at the height of the bloody offensive, the author quickly realized the statistic of the short life expectancy of a machine gunner. This updated edition reveals what happened to the heroes of the 5th Marines and includes a new photo insert.